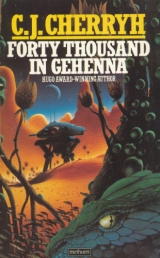

Текст книги "Forty Thousand in Gehenna"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

Jane did not. Jin’s daughter, it might be; or one of his brothers’. Or something that had happened beneath the hill. She fed it, cared for it, saw a darkhaired girl toddling for her father’s hands, or going after him with smaller paces, or squatting to play with Ruffles–at this she shuddered, but said nothing–Elly followed her grandfather everywhere, and he showed her flitters and snails and the patterning of leaves.

That was well enough. It was all Jane asked of life, to keep a little peace in it.

The fields went smaller. The azi who had fled did some independent farming, over by the cliffs, so the rumor ran. Gallin died, a cough that started in the winter and went to pneumonia; that winter carried off Bilas too. They went no longer outside the Camp–the Calibans came here, too…made mounds on the shore, between them and the fishing; and only that roused them to fight the intruders back.

But the calibans came back. They always did.

Jane sat in the summer sun the year her father died, and saw Elly half grown–a darkhaired young woman of wiry strength who ran with azi youths. She cared not even to call her back.

That was the way, at the end of it all, she felt about the child.

xii

Year 49, day 206 CR

There were more and more graves–of which the born‑man Ada Beaumont had been the first. Jin elder knew them all: Beaumont and Davies, Conn and Chiles, Dean who had birthed his son; Bilas and White and Innis; Gallin and Burdette, Gutierrez and all the others. Names that he had known; and faces. One of his own sibs lay here, killed in an accident…a few other azi, the earliest lost, but generally it was not a place for azi. Azi were buried down by the town, where his Pia lay, worn out with children; but he came here sometimes, to cut the weeds, with a crew of the elders who had known Cyteen.

So this time he brought the young, a troop of them, his daughter Pia’s children and three of his son Jin’s; and some of Tam’s, and children who played with them, a rowdy lot. They trod across the graves and played bat‑the‑stone among the weeds.

“Listen,” Jin said, and was stern with them until they stopped their games and at least looked his way. “I brought you here to show you why you have to do your work. There was a ship that brought us. It put us here to take care of the world. To take care of the born‑men and to do what they said. They built this place, all the camp.”

“Calibans made it,” said his granddaughter Pia‑called‑Red and the children giggled.

“ Wemade it, the azi did. Every last building. The big tower too. We built that. And they showed us how, these born‑men. This one was Beaumont: she was one of the best. And Conn–everyone called him the colonel; and he was stronger than Gallin was… Stop that!” he said, because the youngest Jin had thrown a stone, that glanced off a headstone. “You have to understand. You behave badly. You have to have respect for orders. You have to understand what this is. These were the born‑men. They lived in the domes.”

“Calibans live there now,” another said.

“We have to keep this place,” Jin said, “all the same. They gave us orders.”

“They’re dead.”

“The orders are there.”

“Why should we listen to dead people?”

“They were born‑men; they planned all this.”

“So are we,” said his eldest grandson. “We were born.”

It went like that. The children ran off along the shore, and gathered shells, and played chase among the stones. Ariels waddled unconcerned along the beach, and Jin 458 shook his head and walked away. He limped a little, arthritis setting in, that the cold nights made worse.

He worked in the fields, but the fields had shrunk a great deal, and it was all they could do to raise grain enough. They traded bits and pieces of the camp to their own children in the hills–for fish and grain and vegetables, year by year.

He walked back to the camp, abandoning the children, avoiding the place where the machines that had killed Beaumont rusted away.

Some azi still held their posts in the domes, and the tower still caught the sun, a steel spire rising amid the brush and weeds. Flitters glided, a nuisance for walkers. Ariels had the run of all the empty domes in maincamp, and trees grew tall among the ridges which had advanced across the land, creating forests and grassy hills where plains and fields had been. Most of the born‑men had gone to the high hills to build on stone, or their children had. In maincamp only the graves had human occupants.

He was old, and the children went their own way, more and more of them. His son Mark was dead, drowned, they said, and he had not seen the rest of his sons in the better part of a year. Only his daughter Pia came and went from them, and brought him gifts, and left her children to his care…because, she said, you’re good at it.

He doubted that, or he might have taught them something. The shouts of children pursued him as he went; they played their games. That was all. When they grew up they would go to the hills and go and come as they pleased. Himself, he kept trying with them, with life, with the world. This was not the world born‑men had planned. But he did the best he knew.

V

OUTSIDE

i

Excerpt, treaty of the new territories

“Union recognizes the territorial interests of the Alliance in the star systems variously named the Gehenna Reach or the MacLaren Stars; in its turn the Alliance will undertake to route fifty percent of trade with these systems through Union gateway ports after such time as a positive trade balance has been achieved;…further…that the defense of these territories will be maintained jointly by the terms of the Accord of Pell…”

ii

Private apartments, the First of Council, Cyteen Capital

“It’s only come a few years ahead of expectations.” Councillor Harad’s face, naturally long, was longer still in his contemplation. He paused, poured himself and the Secretary each a glass of wine–lifted his, thoughtfully. “This is our purchase. Pell wine, from the heart of Alliance.”

“You would have opposed the signing.”

“Absolutely not.” Harad sipped slowly and settled again in his chair. The window overlooked the concrete canyons of the city and the winding silver sheen of the Amity River. Outside, commerce came and went. “As it is, Alliance ships go on serving our ports. No boycott. And the longer that’s true–the less likely it becomes. So the colonies were well spent. They’ll keep the Alliance quite busy.”

“They may just lift the colonists off, you know. And if one colony should resist, we’ll have a crisis on our hands.”

“They won’t. There’ll be no untoward incident. Maybe Alliance knows they’re there. We’ll have to break that news, at least, now the treaty’s signed. They’ll take that hard, if they don’t know. They’ll be demanding records, access to files. They’ll know, of course, the files will be culled; but we’ll cooperate. That’s at the bureau level.”

“It seems to me a halfwitted move.”

“What?”

“To give up. Oh, I know the logic: hard worlds to develop; and we’ve hurried Alliance into expansion–but all things considered, maybe we should have thrown more into it. We may regret those worlds.”

“The economics of the time.”

“But not our present limits.”

Harad frowned. “I’ve looked into this. My predecessor left us a legacy. Those worlds were all hard. I’ll tell you something I’ve known since first I opened the file. The Reach colonies were all designed to fail.”

The Secretary favored him with a cold blue stare. “You’re serious.”

“Absolutely. We couldn’t afford to do it right. Not in those years. It was all going into ships. So we set them up to fail. Ecological disaster; a human population that would survive but scatter into impossible terrain. That’s what they’ll find. No mission was ever backed up. No ships were dispatched. The colonists never knew.”

“Union citizens–Union lives–”

“That was the way of it in those days. That’s why I supported the treaty. We’ve just dictated Alliance’s first colonial moves, handed them a prize that will bog them down in that direction for decades yet to come. Whatever they do hereafter will have to be in spite of what they’ve gained.”

“But the lives, Councillor. Those people waiting on ships that never came–”

“But it accomplished what it set out to do. And isn’t it, in all accounts, far cheaper than a war?”

VI

RE‑ENTRY

Military Personnel:

Col. James A. Conn, governor general d. 3 CR

Capt. Ada P. Beaumont, It. governor, d. year of founding

Maj. Peter T. Gallin, personnel, d. 34 CR

M/Sgt. Ilya V. Burdette, Corps of Engineers, d. 23 CR

Cpl. Antonia M. Cole, d. 32 CR

Spec. Martin H. Andresson, d. 22 CR

Spec. Emilie Kontrin, d. 31 CR

Spec. Danton X. Norris d. 22 CR

M/Sgt. Danielle L. Emberton, tactical op., d. 22 CR

Spec. Lewiston W. Rogers, d. 22 CR

Spec. Hamil N. Masu, d. 22 CR

Spec. Grigori R. Tamilin, d. 22 CR

M/Sgt. Pavlos D. M. Bilas, maintenance, d. 34 CR

Spec. Dorothy T. Kyle, d. 40 CR

Spec. Egan I. Innis, d. 36 CR

Spec. Lucas M. White, d. 32 CR

Spec. Eron 678‑4578 Miles, d. 49 CR

Spec. Upton R. Patrick, d. 38 CR

Spec. Gene T. Troyes, d. 42 CR

Spec. Tyler W. Hammett, d. 42 CR

Spec. Kelley N. Matsuo, d. 44 CR

Spec. Belle M. Rider, d. 48 CR

Spec. Vela K. James, d. 25 CR

Spec. Matthew R. Mayes, d. 29 CR

Spec. Adrian C. Potts, d. 27 CR

Spec. Vasily C. Orlov, d. 44 CR

Spec. Rinata W. Quarry, d. 39 CR

Spec. Kito A. M. Kabir, d. 43 CR

Spec. Sita Chandrus, d. 22 CR

M/Sgt. Dinah L. Sigury, communications, d. 22 CR

Spec. Yung Kim, d. 22 CR

Spec. Lee P. de Witt, d. 48 CR

M/Sgt. Thomas W. Oliver, quartermaster, d. 39 CR

Cpl. Nina N. Ferry, d. 45 CR

Pfc. Hayes Brandon, d. 48 CR

Lt. Romy T. Jones, special forces, d. 22 CR

Sgt. Jan Vandermeer, d. 22 CR

Spec. Kathryn S. Flanahan, d. 22 CR

Spec. Charles M. Ogden, d. 22 CR

M/Sgt. Zell T. Parham, security, d. 22 CR

Cpl. Quintan R. Witten, d. 22 CR

Capt. Jessica N. Sedgewick, confessor‑advocate, d. 38 CR

Capt. Bethan M. Dean, surgeon, d. 46 CR

Capt. Robert T. Hamil, surgeon, d. 32 CR

Lt. Regan T. Chiles, computer services, d. 29 CR

Civilian Personnel:

Secretarial personnel: 12

Medical/surgical: 1

Medical/paramedic: 7

Mechanical maintenance: 20

Distribution and warehousing: 20

Robert H. Davies, d. 3 CR

Security: 12

Computer service: 4

Computer maintenance: 2

Librarian: 1

Agricultural specialists: 10

Harold B. Hill, d. 32

CR Geologists: 5

Meteorologist: 1

Biologists: 6

Marco X. Gutierrez, d. 39 CR

Eva K. Jenks, d. 38 CR

Jane Flanahan‑Gutierrez, CR 2–CR 50

Elly Flanahan‑Gutierrez, b. 23 CR–

Education: 5

Cartographer: 1

Management supervisors: 4

Biocycle engineers: 4

Construction personnel: 50

Food preparation specialists: 6

Industrial specialists: 15

Mining engineers: 2

Energy systems supervisors: 8

ADDITIONAL NONCITIZEN PERSONNEL.

“A” class: 2890

Jin 458‑9998

Pia 86‑687, d. 46 CR

(chart)

“B” class: 12389

“M” class: 4566

“P” class: 20788

“V” class: 1278

i

Communication: Alliance security to AS Ajax “…survey and report.”

ii

Year 58, day 259 CR

The ship came down, all long‑range contact negative, and settled at the site the orbiting scan had turned up.

And Westin Lake, Alliance Forces, ordered the hatch opened on a close view of the land; on a sprawl of human‑made huts, on an eerie wilderness beyond, a landscape different than the sketchy Union charts told them they should find.

Someone swore.

“It’s not right,” another said. That was more than true.

They waited two hours, expecting approach: it failed, except for a few small lizards.

But trails of smoke went up, among the trees and the huts–the smoke of evening fires.

iii

There had been a sound like thunder, disturbing the too‑close sickroom where the old man lay, amid a clutter of wornout blankets. An ariel perched on the windowsill, and another enjoyed a permanent habitation in the stack of baskets by the door. The sound stopped. “Is it raining?” Jin elder asked, stirring from that sleep that had held him neither here nor there. Pia tried to tell him something.

And he was perplexed, because Jin Younger was there too, that tall man sitting on the chest by Pia. There was silver in his son’s beard, and in Pia’s hair. When had they gotten so old?

But Pia– hisPia–was dead long ago. Her sibs had gone close after her; the last of his had gone this spring. All were dead, who had known the ships. None had lived so long as he–if it was life, to lie here dreaming. There was none that recalled the things he remembered. The faces confused him, not clear types such as he had known, but still, much like those he had known.

“Mark,” he called; and: “Green?” But Mark was dead and Green was lost, long ago. They told him Zed had vanished too.

“I’m here,” someone said. Jin. He recalled then, and focused on the years in the curious way things would slip into focus and go out again. His children had come back to him, at least Jin and Pia had.

“I don’t think he understands.” Pia’s voice, a whisper, across the room. “It’s no good, Jin.”

“Huh.”

“He always used to talkabout the ships.”

“We could take him outside.”

“I don’t think he’d even know.”

Silence a moment. Darkness a moment. He felt far away.

“Is he breathing?”

“Not very strong.–Father. Do you hear? The ships have come.”

Over the fields of grain, high in blue skies, a thin splinter of silver. He knew what it was to fly. Had flown, once. It was a hot day. They might swim in the creek when they were done with harvest, with the sun heating the earth, and making the sweat run on his back.

“Father?”

Into the bright, bright sun.

iv

Pia‑now‑eldest walked out into the light, grim, looked round her at the knot of hangers‑on…the young, the scatter of children they had sent to Jin. “He’s gone,” she said.

Solemn faces. A handful of them, from about a hand of years to twice that. Solemn eyes.

“Go on,” Pia said, and picked up a stick. “We get first stuff. Get. Go to Old Jon. Go to Ben. Go wherever you like. There’s nothing for you here.”

They ran. Some cried. They knew her right arm–one of the Hillers, who seldom came into town at all, Pia Eldest–no timid towndweller they could put anything off on. She followed them with her eyes, down the row of ramshackle limestone houses, the last ragtag lot of youngers Old Jin had had. They might be kin or just strays. The old man had been readier than most to take them in. The worst stayed with Old Jin. He never hit them, and they had stolen his food until Pia found it out; and then there had been no more stealing, no.

She went inside, into the stench of the unkept house, into the presence of the dead, suddenly lacking an obligation, realizing that she had nothing more to do. Her brother Jin was going through the chest, had laid claim to the other blanket besides the one Old Jin was wrapped in. She frowned at that, stood there leaning on her stick.

“You don’t want anything?” Jin asked her. He stood up, a half a head taller. They wore their hair short, alike; wore boots of caliban hide and shirts and breeches of coarse town weave; looked like as all Old Jin and Pia’s offspring. “You can have the blanket.”

That surprised her. She shook her head, still scowling. “Don’t want anything. Got enough.”

“Go on. You fed him the last three years.”

She shrugged. “Your food too.”

“You made the trips.”

“So. No matter. Didn’t do it for that.”

“Owe you for the blanket,” her brother said.

“Collect it someday. What’s town to us? I don’t want what smells of it.”

Jin looked aside, on the small and withered form beneath the other blanket. Looked at her again. “We go?”

“I’ll wait for the burying.”

“We could take him up in the hills. There’s those would carry.”

She shook her head. “This is his place.”

“This.” Jin rolled the razor and the plastic cup into the blanket, tucked them under his arm. “Filth. Get up to the hills. Those new born‑men–they’ll come here. They’ll be trouble, that’s all. Jin’s ships. He thought everything the main‑campers did was all right. How could he know so much and so little?”

“I had myself a main‑camper once. He said–he said the old azi had to think like Jin, that’s all.”

“Maybe they did. Anything the main‑campers wanted. Only now there’s new main‑campers. You remember how it was. You remember what it was, when old Gallin had the say in main‑camp. That’s what it’ll be again. You mind me, Pia, you don’t wait for the burying or they’ll have you plowing fields.”

She spat, half a laugh.

“You mind me,” Jin said. “That’s how it was. Mark and Zed and Tam and I–we ran out on it.”

“So did I. It wasn’t hard.” She took a comb Jin had left. “This. I’ll keep this.”

“They’ll be coming here.”

“They’ll bring things.”

“Tape machines. They’ll catch the youngers and line us up in rows.”

“Maybe they should.”

“You thinking like him?”

She walked away to the door, looked out above the abandoned, caliban‑haunted domes and the fallen sun‑tower where vines had had their way, where the town stopped. The ship sat there in the distant plain, shining silver, visible above the roofs.

“You don’t go,” Jin argued with her, coming and taking her shoulders. “You don’t be going out there talking to those born‑men.”

“No,” she agreed.

“Forget the stinking born‑men.”

“Aren’t we?”

“What?”

“Born‑men. We were born here.”

“I’m going,” Jin said. “Come along.”

“I’ll walk with you to the trail.” She started on her way. There was nothing to carry but the staff, and what Jin chose to keep; and behind them, the town would break in and steal.

So Old Jin was gone.

And she was sitting by the doorway when they brought the New Men to her.

They disturbed her with their strangeness, as they disturbed the town. There were those who were ready to be awed by them, she saw that, but she looked coldly at the newcomers and kept her mind to herself.

Their clothes were all very fine, like the strange tight weave which the looms the town made nowadays could never duplicate. Their hair was short as Killers wore it and they smelled of strange sharp scents.

“They say there was a man here who came on the ships,” the first of them said. He had a strange way of talking, not that the words were unclear, just the sound of them was different. Pia wrinkled her nose.

“He died.”

“You’re his daughter. They said you might talk to us. We’d like you to come and do that. Aboard the ship, if you’d like.”

“Won’t go there.” Her heart beat very fast, but she kept her face set and grim and unconcerned. They had guns. She saw that. “Sit.”

They looked uncomfortable or offended. One squatted down in front of her, a man in blue weave with a lot of metal and stripes that meant importance among born‑men. She remembered.

“Pia’s your name.”

She nodded shortly.

“You know what happened here? Can you tell us what happened here?”

“My father died.”

“Was he born?”

She pursed her lips. All the rest knew that much, whatever it meant, because it had never made sense to her, how a man could not be born. “He was something else,” she said.

“You remember the way it was at the beginning. What happened to the domes?” The gesture of a smooth, white hand toward the ruins where calibans made walls. “Disease? Sickness?”

“They got old,” she said, “mostly.”

“But the children–the next generation–”

She remembered and chuckled to herself, grew sober again, thinking on the day the born‑men died.

“There were children,” the man insisted. “Weren’t there?”

She drew a pattern in the dust, scooped up sand and drew with it, a slow trickling from her hand.

“Sera. What happened to the children?”

“Got children,” she said. “Mine.”

“Where?”

She looked up, fixed the stranger with her stronger eye. “Some here, some there, one dead.”

The man sucked in his lips, thinking. “You live up in the hills.”

“Live right here.”

“They said you were out of the hills. They’re afraid of you, sera Pia.”

It was not, perhaps, wise, to make Patterns in the dust. The man was sharp. She dumped sand atop the spiral she had made. “Live here, live there.”

“Listen,” he said earnestly, leaning forward. “There was a plan. There was going to be a city here. Do you know that? Do you remember lights? Machines?”

She gestured loosely toward the mirrors and the tower, the wreckage of them amid the caliban burrowings in main camp. “They fell. The machines are old.” She thought of the lights aglow again; the town might come alive with these strangers here. She thought of the machines coming to life again and eating up the ground and levelling the burrows and the mounds. It made her vaguely uncomfortable. Her brother was right. They meant to plow the land again. She sensed that, looking into the pale blue eyes. “You want to see the old Camp? Youngers’ll take you there.”

And on the other side there was lack of trust, dead silence. Of course, they had seen the mounds. It was strange territory.

“Maybe you might go with us.”

She got up, looked round her at the townfolk, who tried to be looking elsewhere, at the ground, at each other, at the strangers. “Come on then,” she said.

They talked to their ship. She remembered such tricks as they used, but the voices coming out of the air made the children shriek. “Old stuff,” she said sourly, and reached for Old Jin’s stick that he had had by the door, leaned on it as if she were tired and slow. “Come on. Come on.”

Two of them would go with her. Three stayed in the village. She walked with them up the road, in amongst the weeds and ruins. She walked slowly, using the stick.

And when she had gotten into the wild place she hit them both and ran away, heading off among the caliban retreats until her side ached and she needed the stick.

But she was free, and as for the mounds, she knew how to skirt them and where the accesses were to be avoided.

She came by evening into the wooded slopes, up amongst the true, rock‑hearted hills.

Someone whistled, far and lonely in the woods where flitters and ariels darted and slithered. It was a human sound. One of the watchers had seen her come.

Home, the whistle said to her. She whistled back; Pia, her whistle said. There were friends and enemies here, but she had her knife and she brought away a comb and her father’s stick, confident and set upon her way.

At least Old Jin had not been crazy. She knew that now. She had seen the ships come, and she remembered the born‑men who had lived in the domes, who had died and mingled their types with azi, some in the hills and some few scratching the land with wooden plows.

There were ships again and born‑men to own the world.

Azi marching in rows, her brother Jin had said. But she was not azi and she would never march to their orders.

v

Strangers.

Green wrinkled his nose and blinked in the light, perceiving disruption in the Pattern made on the plain. There was a new motion now. He felt the stirrings underground recognizing it.

The disquiet grew extreme. He dived back into the dark, finding his way with body and direction‑sense rather than with eyes. Small folk skittered past him as he went, muddy slitherings of long‑tailed bodies past his bare legs as he stooped and hastened along in that surefooted gait he had learned very long ago, hands before him in the dark, bare feet scuffing along the muddy bottom. His toes met a serpentine and living object in the dark, his skin felt an interruption in the draft that should blow in this corridor, his ears picked up the sough of breathing: he knew what his fingers would meet before they met it, and he simply scrambled up the tail and over the pebble‑leathery back, doing the great brown less damage than its blunt claws could do to him in getting past. The brown gave a throaty exhalation, flicked an inquisitive tongue about his shoulders and when he simply scurried on, it slithered after.

It wanted to know then. It was interested. Green darted up again, taking branches of the tunnels which led nearer the strangers. He was, after all, Green, and old, almost the oldest of his kind, in his way superior to the elder brown which whipped along after him. It wanted to know; and he changed his plans and darted up again to daylight to show it.

When he had come to the light again, up where trees crested the mound, where he had free view of the town and the shining thing which had come to rest in the meadow, the brown squatted by him to look too.

He made the Pattern for it. He offered up what he had, making the spirals rightwise up to a point and leftwise thereafter.

The brown moved heavily and seized up a twig fallen from the trees, crunched it in massive jaws. The crest was up. The eyes were more dark than gold. Green sat with the muscles at his own nape tightening, lacking expression for his confusion. The brown was distraught. It was everywhere evident.

It nosed him suddenly, directing him back inside the mound. He reached the cool safe dark and still it pushed at him, herding him toward the deepest sanctuary.

There were others gathered in the dark. They huddled together and in time one of the browns came to herd them further.

It was days that they travelled in that way, until they had come far upriver, to the new mounds, and here they stayed, able to take the sun again, here where calibans made domes and walls and caliban young and grays came out to sun, heedless of the danger westward.

vi

T51 days MAT: Alliance Probe Boreas ;

Report, to be couriered to Alliance Security Operations under seal COL/M/TAYLOR/ASB/SPEC/OP/NEWPORT‑PROJECT/

…initial exploration in sector A on accompanying chart #a‑1 shows complete collapse of Union authority. The prefab domes are deserted, overgrown with brush. The solar array is indicated by letter aon chart #a‑1, lying under the wreckage of the tower; brush has grown over most of it. Inquiry among inhabitants produces no clear response except that the fall occurred perhaps a decade previous. This may have been due to weather.

On the other hand, the prefab domes sit amid a convolute system of ridges identical to those observed throughout the riverside and named in orbiting survey reports 1‑23. We have found the caliban mounds predicted by Union information on the site, but there is no close agreement between present circumstance and Union records. If one example might illustrate the disturbing character of the site, chart #a‑1 may serve: it is inconceivable that the original colony would have established their domes and fields in the center of the mound system. What was level terrain in the Union records is now a corrugated landscape overgrown with brush. When asked what became of the residents of the domes, the townsmen answer that some of them came to the town, and some went to the hills. Orbiting survey does show (chart #a‑2) a second settlement in the hills about ten kilometers from the town, but considering the potential risk of extending interference without understanding the interrelation of the systems, the mission has confined itself to the perimeter outlined for the colony.

There was, however, one interview with a woman, one Pia, no other name known, who has vanished from the community after assaulting mission personnel she had agreed to guide (see sec. #2 of this report) and who may have retreated to the hills. (The transcript of the Pia interview is included as document C, sec. 12. The economy of the town and that of the dwellers in the hills are perhaps linked in trade: see documents in C section, especially sec. 11. )

When questioned regarding the Calibans the townsmen generally look away and affect not to have heard; if pressed, they refuse direct answer. The interviewers have not been able to ascertain whether the townsmen hold the calibans in some fear or whether they distrust the interviewers.

The mission finds the townsmen politically naive, existing in a neolithic lifestyle. The individual Pia recalled technology, and no inhabitants seem surprised at modern equipment, but if there is any technology among them other than a few items originally imported from offworld, the mission has not observed it. They plow with hand‑pushed wooden plows, have no metals except what was originally imported, and apparently do not have high temperature forging techniques necessary to work what metal they do have. Weaving and pottery are known, and may conceivably have been an independent discovery. If there is ritual, religion, or ceremonies of passage, we have yet to discover them, unless there is in fact some superstition regarding the calibans.

There is no writing except in primitive accounts of food inventory. Spelling is not regular, nor is the majority literate beyond the capacity to make tallies. There has been some linguistic change, on which we might derive more information if we knew the world of origin of these Union colonists and the azi (see document E). The accent is distinctive after less than a century of isolation, indicative of a very early breakdown of formal education; but the forms of standard grammar remain, not uncommon in azi‑descended populations where precise adherence to instruction has been tape‑fed as a value.

The local nomenclature has changed: few townsmen recognize Newport as the name of the colony. Their word for their world is Gehenna, while the primary is called simply The Sun, and the principal river on which they have settled they name Styx. The literary allusion is not known to them.

There is no indication that the inhabitants understand any political affiliation to Union, or that there will be any active opposition to Alliance operations or governance.

There is, however, a second and more serious consideration, and it is one which the mission hesitates, in the absence of more evidence, to present to the Bureau. While Union documents describe the highest lifeform as nonsapient, evidence points to caliban intrusion into human living area during the colony’s height. It would be speculative at this point to suggest that caliban activity may have led directly to the decline of the colony, but it is remarkable that the decline has been so thorough and so rapid. Dissension and political strife among the colonists might have disrupted human civilization, but the town, of considerable population, does not show any fear or carry any weapons excepting utilitarian objects such as knives or sticks, and does not threaten with them. We do not yet have a census, but the town is a little smaller than we would expect. Granted the usual Union colonial base, the world population in fifty years might well exceed a hundred thousand by natural reproduction alone.