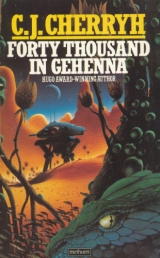

Текст книги "Forty Thousand in Gehenna"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

So I don’t see anything else to do.

xxxviii

?

Cloud Tower: the lower section

There was food. McGee went to it by the smell, in the dark, not needing the calibans to guide her. But one was there. She had touched it, knew by the size, guessed by the texture of the skin that it was one of the grays.

Shepherds, she thought of them. She had been terrified at first, of the claws, the hard, bony jaws, the sinuous force of them. They had knocked her down, repeatedly, until she learned to use her ears.

There were other things in the dark: ariels. They skittered here and there and of them she had never been afraid, had kept them close when she could, because they seemed friendly.

There was a big brown hereabouts; she had felt the smoothness on his side. It was Scar, and Elai had lent him. She was grateful, and stayed close to him when she could.

Even of the Weirds she had lost her awe. They were strange, but gentle, and touched her with their spidery fingers, embraced her, held her when she was most afraid.

Once in this fathomless dark, in this waking sleep, she had been intimate with one, and more than once: that was the thing that she had most trouble to reckon with, that the thing she had dreaded most had happened, and that she had (perhaps) been the aggressor in it, having forgotten all she was, with some faceless man, a Weird, a voiceless priest of calibans.

She had lain listless for a long time after, for she had lost her objectivity, and she was compassless in more than the robbery of her senses.

Then: McGee, she thought, you did that. That was you. Not their fault. What if it had been? Get up, McGee.

And in one part of her mind: He’ll know me, outside this place. But I won’t know him.

And in another: You don’t care, McGee. This is real. The dark. This place. It’s a womb for growing in.

So grow, McGee.

She scrambled along the earthen walls, found the food left for her and ate, raw fish, which had become a neutral taste to her, something she had learned to abide. Something light skittered over her knees and she knew it was an ariel begging scraps. She gave it the head and bit by bit, the offal and the bones.

God knows what disease I’ll take, the civilized part of her had thought, of muddy hands and raw fish. I’m stronger than I thought, she reckoned now. She had not reckoned a great deal about herself lately, here in the dark. I’m wiser than I was.

The ariel slithered away with a flick of its tail. That presaged something.

A gray came then. She heard it moving. She drew to the side of the passage in case it wanted through. It arrived with a whispering of its leathery hide against the earth, a caliban in quiet approach. It nosed at her; she patted the huge head and it kept nudging. Move, move. So she must.

She went with it, this caliban‑shepherd, up and up.

This was different. There had been no such ascent in her other wanderings. They were going out to the light. Have I failed? she wondered. Am I being turned out? But no Weird had tutored her, none had been near her in–she had lost track of the time.

Daylight was ahead, a round source of sun. She went more slowly now, to accustom her eyes, and the gray went before her, a sinuous shape moving like a shadow into what proved twilight, a riot of color in the sky.

But we have left the Towers, McGee thought, rubbing at her eyes. The river was before her. Somehow they had come out by the river, where caliban mounds were, beside the fisher nets.

I should find Elai, call the Base. How many days?

Something overshadowed her, on the ridge. She looked about, blinking in the light, with tears running down her face. It was a great brown.

Her gray had stayed. It offered her a stone, laying it near. She saw a nest of ariels, a dozen dragon‑shapes curled up in a niche in the bank, where stones had been laid. It was a strange moment, a stillness in the air. “Here I am,” she said, and the sound of her own voice dismayed her, who had not heard a voice in days. It intruded on the stillness.

An ariel wriggled out and offered her a stone. It stayed, flicking collar fringes, lifting its tiny spines.

She, squatted, took the stone and laid it down again.

It brought another, manic in its haste.

xxxix

204 CR, day 300

Message, R. Genley from transStyx, to Base Director’s office.

I am not receiving McGee’s regular reports. Should I come in?

Message, Base Director to R. Genley

Negative. Dr. McGee is still on special assignment.

Memo, Base Director to Security Chief

Refer all inquiries about Dr. McGee to me.

I am more than a little concerned about this prolonged silence from McGee. Prepare a list of options in this case.

Message, Base Director to Gehenna Station.

Request close surveillance of the Cloud River settlement. Relay materials to this office…

transStyx: Green Tower

“My father,” Jin said, in the sunlight, in the winter sun, when the wide fields of Green Tower lay plowed and vacant. Forest stretched about them to the east, the marsh to the west. The wind lifted Jin’s dark hair, blew it in webs; the light shone on him, on Thorn, lazy beside the downward access. “My father.” His voice was low and warm and his hand that had rested on the walls rested on Genley’s shoulder, drew him close, faced him outward as he pointed, a sweep about the land. “This is mine. This is mine. All the fields. All the people. All they make. And do you know, my father, when I took it into my hands I had one tower. This one. Look at it now. Look, Gen‑ley. Tell me what you see.”

There was a craziness in Jin sometimes. Jin played on its uncertainties, unnerved some men. Genley looked on him with one brow arched, daring to dare him back.

“Would you think,” Jin said, “that a man has tried to kill me today?”

It was not a joke. Genley saw that and the humor fell from his face. “When? Who?”

“Mes Younger sent this man. This was a mistake. Mes will learn.” Jin set both his hands on the rim of the wall, fists clenched. “It’s this woman, Gen‑ley. This woman.”

“Elai.”

“ MaGee.” Jin rounded on him, looked up at him, his face flushed with rage. “This conniving of women. This thing goes on. Jin is a fool, they say; he lets the starmen play with him. He listens to them while they talk to this Elai and this Elai learns anything she wants from MaGee. And if Jin is a fool, then fools can try him, can’t they?”

Genley took in his breath. “I’ve warned Base about this.”

“They don’t listen to you.”

“I’ll file a complaint with them if you’ve got something definite I can say to them. I’ll make them understand.”

Jin stared up at him, a shorter man. His veins swelled; his nostrils were white. “What would they like to hear?”

“What she’s doing. They don’t know where she is right now. Do you?”

“They don’t know where she is. She’s with Elai. That’s where she is.”

“Tell me what she’s doing and I’ll tell them.”

“ No!” Jin flung his arm in a gesture half a blow, strode off toward Thorn. The caliban had risen, his collar erect. Jin turned back again, thrust out his arm. “No more com, Gen‑ley. My father, who gives me advice. I’m sending you to Parm. You. This Mannin, this Kim.”

“Let’s talk about this.”

“No talk.” He flung the arm northward, an extravagant gesture. “I’m going north to kill this man. This man who thinks I’m a fool. You go to Parm Tower. You think, you think, Genley, what this woman costs.”

He disappeared down the access. Thorn delayed, a cold, caliban eye turned to the object of the anger, then whipped after Jin.

Genley stood there drawing deep breaths, one after the other.

xl

204 CR, day 321

Cloud Towers

“MaGee,” said Elai.

The star‑man looked at her, met her eyes, and Elai felt the stillness there. The stillness spread over all the room and into her bones. Her people were there. There were calibans. They brought MaGee to her, this thin, hard stranger with loose, tangled hair, who wore robes and not the clothes she had worn, who could have worn nothing and lost none of that force she had.

But MaGee was not MaGee of the seashore, of the summer; and she was not the child.

“Go,” Elai said, to the roomful of her people. “All but MaGee. Go.”

They went, quietly, excepting Din.

“Out,” said Elai, “boy.”

Din went out. His caliban followed. Only Scar remained. And the grays.

“A man came from behind the wire,” said Elai. “Four days ago. We sent him away. He asked how you were.”

“I’ll have to call the Base,” MaGee said.

“And tell them about Calibans?”

MaGee was silent a long while. It became clear she would not answer. Elai opened her hand, dismissing the matter, trusting the silence more than assurances.

“No words,” said MaGee finally, in a hoarse, strange voice. “You knew that.”

Elai gestured yes, a steadiness of the eyes.

And MaGee picked it up. Every tiny movement. Or at least–enough of them.

“I want to go back to my room,” MaGee said. “There’s too much here.”

Go, Elai signed in mercy. In tenderness. MaGee left, quietly, alone.

204 CR, day 323

Message, E. McGee to Base Director

Call off the dogs. Reports of my death greatly exaggerated. Am writing report on data. Will transmit when complete.

204 CR, day 323

Message, Base Director to E. McGee

Come in at once with full accounting.

204 CR, day 323

Message, E. McGee to Base Director

Will transmit when report is complete.

204 CR, day 326

Notes, coded journal Dr. E. McGee

I’ve had trouble starting this again. I’m not the same. I know that. I know–

xli

204 CR, day 328

Cloud Tower

Security had sent him. Kiley. A decent man. McGee had heard about him, or at least that something was astir, and then that it was Outsider; and when she heard that she knew.

She had put on her Outsider‑clothes. Cut her hair. Perfumed herself with Outsider‑smells. She went there, to the hall, where the riders would bring the Outsider.

“Kiley,” she said, when Elai said nothing to this intruder.

He was one of the old hands. Stable. His eyes kept measuring everything because that was the way he was trained. He would know when someone was measuring him.

“Good to see you, doctor,” Kiley said. “The Director’d like to see you. Briefly. Sent me to bring you.”

“I’m in the middle of something. Sorry.”

“Then I’d like to talk to you. Collect your notes, take any requests for supplies.”

“None needed. You don’t have to send me signals. I can say everything I have to say right here. I don’t need supplies and I don’t need rescue. Any trouble at the Base?”

“None.”

“Then go tell them that.”

“Doctor, the Director gave this as an order.”

“I understand that. Go and tell him I have things in progress here.”

“I’m to say that you refused to come in.”

“No. Just what I said.”

“Could you leave if you wanted to?”

“Probably. But I won’t just now.”

“Yes, ma’am,” Kiley said tautly.

“Let someone take him outside the Towers,” McGee said. “This man is all right.”

Elai made a sign that was plain enough to those that knew, and Maet, an older rider, bestirred himself and gave Kiley a nod.

Later:

You stay here, Elai said, not with words, but she made it clear as it had always been.

Notes, coded journal Dr. E. McGee

I can write again. It’s hard. It’s two ways of thinking. I have to do this.

There’s a lot–

No. Maybe I’ll write it someday. Maybe not. No one needs to know that. I’ve talked to calibans. A couple of ideas. Finally.

It’s not too remarkable, talking tocalibans. They pick up a lot of what we do.

But after all that time I was sitting there playing put and take with ariels and making no sense at all–they’re not at all bright, the ariels. You can put and take with them a long time, and then they get to miming your game; and then you don’t know who you’re playing with, yourself or it, because they pick up the way you do things. And the calibans just watching. Until the grays get to moving stones around. And then you know what they’ll do. You know what their body‑moves mean; and that this is a tower, and how they circle that, building it, protecting it. The grays say only simple things. Their minds aren’t much. It’s almost all body language. And a few signs like warningand stop hereand tower. And more I can’t read. This gray shoved dirt around as well as stones. It seemed to play or it was stupider than I thought then; it would come up with dirt sitting on its nose and blink to clear its eyes and dive down again and move more dirt until it built a ridge; and when it would stop, old Scar would come down off that mound and get it moving again, it and others, about three others, I don’t know how many. Maybe more.

And that circle was around me. It wasn’t threatening. It was like protection. It went this way and that, tendrils spiraling off from it, the way the ariels do.

I got brave. I tried putting a stone out in front of Scar, a sun‑warmed one. And that wasn’t remarkable. You can get something out of ariels with that move. But then he came down–stood there staring at me and I stood there staring back into an eye bigger than my head, so big he could hardly see me at that range, and then it dawned on me what his vision is like, that those eyes see in larger scale than I am. I’m movement to him. A hazy shape, maybe.

I got him to say a simple thing to me. He walked round me now that my Place was established; he told me there was trouble toward the northeast: he told me with body language, and then I could see how the spirals were, that the grays had made, that they were mapping the world for me. Conveying their land‑sense to smaller scale‑ Or his land‑sense. Or it was all feeding in, even the ariels.

Calibans write on the world. They write the world in microcosm and they keep changing it, and they don’t have tech. Technology can’t matter to them. Cities can’t. Or civilization. They aren’t men. But that big brain is processing the world and putting it out again; it added me to the Cloud Towers. It stood there staring past me with an eye too big to see me the way I see and all of a sudden I was awed–that’s not a word I use much. Really awed. I wanted to cry because I had gone non‑verbal and I couldn’t get it out and couldn’t take it in because my eyes and my brain aren’t set up for what I was seeing.

And now I’m scared. I’m writing up a report and they’ll think I’m crazy. I can hear what Genley will say: “Now they write. Pull McGee in. She’s been out too long.”

But I get up on the top of the Tower–how calibans must have loved the idea of towers! Their eyes are fit for that. And then I think of the square concrete Base we’ve built and I don’t feel comfortable. We bring our big earthmovers to challenge the grays and we build things with angles.

All over the world calibans build spirals. But here on Cloud and Styx they’ve gone to towers. And human gardens. We’re like the ariels. The grays. Part of the ecumene. Capacity was there. God knows if we touched it off or if we ourselves are an inconsequence to what they’ve been doing all this time, spreading over all the planet, venturing here and there–speaking the same language, writing the same patterns on every rivervalley in the world. But not the same. The spirals vary. They’re saying different things.

Like Styx and Cloud. Like isolate towers and grouped towers.

Two different Words for the world.

xlii

204 CR, day 355

Memo, Director’s office to R. Genley

This office finds it of some concern that reports from your group have become infrequent and much devoted to routine. You are requested to come in for debriefing. There is news concerning Dr. McGee’s effort.

204 CR, day 356

Memo, Base Director to Chief of Field Operations

Genley has failed response to a report. He may be temporarily out of contact, but considering the delicate relations of the two communities and the McGee situation I think we ought to view this silence with alarm. I am transmitting another recall to McGee. I do not think it will produce results, whether she is being held by force or that her refusal is genuine; but it seems one avenue of approach to the Genley matter. I do not consider it wise to inform McGee that Genley’s group is not reporting; we cannot rely on that report remaining secure, in any of several possibilities.

I am furthermore requesting orbiting observation be stepped up.

Advise all observers in the field to observe unusual caution.

Likewise, run a thorough check of all base detection and warning systems. Winter is on us.

205 CR, day 20

Excerpt, Director’s annual report, transmitted to Gehenna Station

…We will be sending up a great quantity of data gathered in the past year. We have enjoyed considerable successes this year in gathering data which still remains to be interpreted… We are still out of touch with the Styx mission and this remains a cause of some concern; and based on Dr. McGee’s study, that concern is increasing, although the chance still remains that Dr. Genley and his staff may have entered into an area of observation which is too sensitive to allow free use of communications…

The reprimand given Dr. McGee has been rescinded due to extraordinary mitigating circumstances. Special note should be made of this fact in all communication with the Bureau.

Her report, which we have placed next in sequence, is a document with which many of the staff take strong issue. Those contrary opinions will follow. But the Committee attaches importance to the report, historically significant in the unique situation of the observer, and containing insights which may prove useful in future analysis.

Report: Dr. E. McGee

…With some difficulty I have succeeded in penetrating the caliban communication system which makes impossible the withholding of any information between Styx and Cloud.

…I have noted that there is a tendency to use Gehennan as a designation for native‑born humans and caliban as distinct from this. This may be incorrect.

The communication mode employed by calibans is, with some significant exceptions, similar to the simple communications used by insects. It is assimplistic to compare the two directly as it would be to compare the vocalizations of beasts to human speech on the grounds that they are similarly produced. The caliban system is of such complexity that I have only been able to penetrate the surface of it, for the communication of such simple concepts as directions and desire for food…

…Part of my reluctance to report has been the difficulty of assimilating and systematizing such data; but more than this is the dismay that I have felt in increasing conviction that the entire body of assumptions and procedures on which my field of xenology is founded has to be challenged.

Among the terms which have to be jettisoned or extensively modified when dealing with calibans: intelligence; culture; trait; language; civilization; symbiont.

Humans native to Gehenna have entered into a complicated communication with this lifeform which I believe to be pursuing a course of its own. All indications are that it is ultimately a peaceful course, though peace and war are human concepts and also to be questioned, presupposing government of some sort, of which calibans may prove biologically incapable.

I make this assertion advisedly. Calibans understand dominance. They apply sudden coercion. They commit suicide and have other maladies of an emotional nature. But what they are doing is not parallel to human ambitions. It goes off from it at such an angle that conflict between humans and calibans can only result from a temporary intersection of territorial objectives.

The term caliban itself is questionable in application, since the original application seems only to have been to the grays. Absolutely there should be no confusion of browns with grays. There has been some speculation that the grays are a sex or a life stage of the caliban. The humans who know them say that this is not the case. Grays and browns seem to be two separate species living in harmony and close association, and if one counts the ariels–there are three.

Further, ariels seem to perform an abstract function of pattern‑gathering. Not themselves intelligent, they are excellent mimes. If a bizarre analogy might be made, the calibans are technological: they use a sophisticated living computer, the ariels, to gather and store information which they themselves process and use in the direction of their heavy machinery, the grays.

I believe that the browns have long since developed beyond the limits of instinctual behavior, that they have learned not so much to manipulate their environment as to interact with it; and further, I believe, (and herein lies the only definition of intelligence applicable in lifeforms which are not analogous to humanity), they have proceeded to abstract purposes in their actions. The Styx and the Cloud are not their Tigris and Nile nor ever should be: we do not have to define them as civilized because such distinctions are outside their ambition, as perhaps ambition lies outside their understanding: in short, their purposes are at an angle to ours. They seem to pursue this abstract purpose collectively, but that should not encourage us to expect collective purpose as an essential part of the definition of intelligent species. The next sapience we encounter may well violate the new criteria we establish to include calibans.

This leads me to a further point, which makes the continuation of my studies absolutely critical at this juncture. This species whose basic mode of encounter is interactive, has begun to interact with humans. It may be possible to communicate to calibans that they may themselves wish to interdict further spread of this interaction. I believe that it is the kind of communication they are capable of understanding. It is the kind of “statement” that is expressible in their symbol system. I am not skilled enough to propose it to them. A six year old native child could phrase it to them–if that human child could comprehend the totality of the problem. If a native adult could. That is our dilemma. So is human ambition. We are very sure that that word is in ourvocabulary.

Which brings me to my most urgent concern.

The calibans Pattern a disturbance on the Styx. This Patterning is increasingly more urgent. That mound‑building which you are no doubt observing in orbital survey on the Cloud, is nothing less than a message, and a rampart, and a statement that danger comes this way.

I am perhaps objective enough to wonder of the two different human/caliban cooperations which have developed, which is the healthier in caliban terms. I think I know. On the Styx they eat grays.

Report, Dr. D. Hampton

…As for Dr. McGee’s assertions, the report is valuable for what may be read between the lines. With personal regret, however, and without prejudice, I must point out that the report is not couched in precise terms, that the effort of Dr. McGee to coin a new terminology does not present us with any precise information as to what calibans are, rather what they are not. A definition in negatives which attempts to tear down any orderly system of comparisons which has been built up in centuries of interspecies observations, including non‑human intelligence, is a flaw which seriously undermines the value of this report. More, the vague suggestions Dr. McGee makes of value structures and good and evil among the calibans leads to the suspicion that she has fallen into the most common error of such studies and begun to believe too implicitly what her informants believe, without applying impartial logic and limiting her statements to observable fact.

I fear that there is more of hypothesis here than substance.

xliii

205 CR, day 35

Styxside

The sun broke through and brought some cheer to the reedy waste about Parm Tower, glancing gold in the water, making black spears of the reeds. A caliban swam there. Genley watched it, a series of ripples in the sheeting gold. Other calibans sat along the bank, in that something‑wrong kind of pose that had been wrong all day.

Riders came in, scuffing along the road upriver. That was what the disturbance had been. Somehow the calibans had gotten it, worked it out themselves in that uncanny way they had.

The riders came. With them came lord Jin.

Every caliban in sight or smell reacted to lord Jin’s Thorn. It swept in like storm, the impression of sheer power that affected all the others and sent calibans and ariels alike into retreat or guard‑posture along the riverside. Jin arrived with his entourage, without word or warning, immaculate and the same as ever–the matter up north was settled, Genley reckoned. Settled. Over. Genley gathered himself up from his rock with the few fish he had speared and came hurrying in, splashing across the shallows and hastening alongside the scant cultivation Parm Tower afforded.

So their isolation was ended. Two months cut off in this relative desolation, two months of fishing and the stink of water and rot and mud and Parm all prickly with having outsiders in his hall. The lord Jin had deigned to come recover them.

Genley did not go running into Jin’s sight. He collected Kim and Mannin from their occupations, Kim at his eternal sketching of artifacts, Mannin from his notes.

“You know the way you have to be with him,” he warned them. “Firm and no backing up. No eagerness either. If we ask about that com equipment right off it’ll likely end up at the bottom of the Styx. You know his ways. And then he’ll be sorry tomorrow. Don’t bring that up. Hear?”

A surly nod from Kim. Mannin looked scared. It had not been an easy time. Kim had had little to say for the last two weeks, to either of them.

“Listen,” said Mannin. “There’s only one thing I want and that’s headed back to Base. Now.”

“We’ll send you back on r and r when we get the leisure,” Genley said. “You just don’t foul it up, you hear? You don’t do it. You muddle this up, I’ll let you get out of it any way you can.”

Mannin sniffed, wiped the perpetual runny nose he had had since they had gotten back to this place. Dank winter cold and clinging mists almost within sight and vastly out of reach of the Base; with the Styx between them and the pleasures of Green Tower, the high, dry land where winter would not mean marsh and bogs.

“Come on,” Genley said, and went off ahead of them.

Your problem, Jin had said once. These men of yours. Your problem.

They went, the three of them, where every other person of status in the community was going, to the Tower, to see what the news was.

xliv

205 CR, day 35

Parm Tower

The hall rustled with caliban movements, nervous movements. Thorn had made himself a place. Parm’s own Claw had moved aside, compelled by something it could not bluff, and below it, other calibans, of those which had come in, sorted themselves into an order of dominances. These had been fighting where they came from: violence was in their mood, and in the mood of their riders, and it was not a good time to have come in. Genley saw that now, but there was no way out. They stood there, against the wall, last to have come in; no caliban defended them. Scaly bodies locked and writhed and tails whipped in sweeps on the peripheries.

“Let’s get out of here,” Mannin said.

“Stay still,” Genley said, jerked at his arm. Mannin had no sense, no understanding what it meant even yet, to give up half a step, a gesture, a single motion in hunter‑company. He smelled of fear, of sweat; he was afraid of calibans. Not singly. En masse. “Use your head, man.”

“Use yours,” Kim said, at his other side. Kim left. Walked out.

Mannin dived after him, abject flight.

So Jin noticed him finally, from across the room where, heedless of it all, he was stripping off his leather shirt. Women of Parm’s band had brought water in a basin. Other men stood muddy as they were, attending the calibans. A scattering of Weirds insinuated themselves and brought some quiet, putting their hands on the calibans, getting matters sorted out.

Jin lifted his chin slightly, staring straight at him while the women washed his hands. Come here, that meant.

Genley crossed the recent battleground, weaving carefully around calibans who had settled into sullen watching of each other. It was a dangerous thing to do. But the Weirds were there. A man knew just how close to come. He did that, and stood facing Jin, who looked him up and down with seeming satisfaction. “Gen‑ley.” The eyes had their old force. But there was a new scar added to the others that were white and pink on Jin’s body. This was on the shoulder, near the neck, an ugly scabbed streak. There were others, already gone to red new flesh. He always forgot how small Jin was. The memory of him was large. Now the eyes held him, dark and trying to overawe him, trying him whether he could go on looking back, the way he tried every man he met.

Genley said nothing. Chatter got nowhere with Jin. It was not the hunters’ style. A lot passed with handsigns, with subtle moves, a shrug of the shoulders, the fix of eyes. There was silence round them now. He was only one of the number that waited on Jin, and some of those were mudspattered and shortfused.

One was Parm; and Parm’s band; one was Blue, mad‑eyed Blue, who was, if Jin had a band, chiefest of that motley group, excepting Jin. A big man, Blue, with half an ear gone, beneath the white‑streaked hair that came down past his shoulders. The hair was strings of mud now.

“How many more?” Parm asked, not signing: Jin’s shoulder was to him.

“I’ll talk to you about that.” Jin never looked at Parm. He gave a small jerk of his head at Blue. “Go on. Clean up–” The eyes came back to Genley. “You I’ll talk to. My father.”

“How did it go?” Genley asked.

“Got him,” Jin said, meaning a man was dead. Maybe more than one. A band would have gone with him. The women. Jin unlaced his breeches, sat down on the earthen ledge to strip off his muddy boots. Women helped him, took the boots away. He stood up and stripped off the breeches, gave them to the women too, and dipped up water in the offered basin, carrying it to his face. It ran down in muddy rivulets. He dipped up a second and a third double handful. The water pooled about his feet. More women brought another basin, and cloths, and dipped up water in cups while he stood there letting them wash the mud off, starting with his hair. It became a lake.