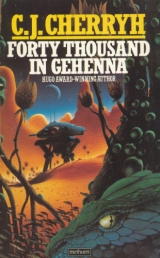

Текст книги "Forty Thousand in Gehenna"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

But when it was all still, it was only the old house all unnaturally clean, as if she had scrubbed it raw. And they ate together, trying to be mother and son.

“They wanted to teach me to write,” he said. “But I already knew. You taught me that.”

“My dad taught me,” she said, which he knew. “We’re born‑men. Just like them.”

“They say I’m good.”

She looked up from her soup and met his eyes, just the least flicker of vindication. “’Course,” she said.

But he hedged all around the other things, like knowing what the world was. He was alone, with things dammed up inside he could never say.

And they had asked him things no one talked about–like the old things: like the books–the books they said the Hillers had. He had said these things not because he was innocent, but because he was afraid, because he was tired, because they wanted these things very, very badly and he was afraid to lie.

He sat across the rough table from his mother and ate his soup, afraid now to have her know how much of a stranger he had already become.

xi

“He’s not Unionist,” the science chief said. “The psych tests don’t turn up much remnant of it. No political consciousness, nothing surviving in his family line.”

“The mother’s got title to a two bed house,” security said, at the same long table in an upper level of the education facility. “Single. Always been single. Says the father’s a hiller and she doesn’t know who.”

“Different story from the boy,” said education. “The father’s got born‑man blood, he says. But he doesn’t know who. We’ve interviewed the mother: she says the boy’s got only herblood and her father was a doctor. She’s literate. She does some small medical work in the town. Not getting rich at it. We give it away; she gets paid in a measure of flour. Hasn’t done any harm at it.”

“Remarkable woman. I’d suggest to bring her in for tests.”

“Might have her doing clinic work,” the mission chief said. “Good policy, to reward the whole family.”

“We’re forming a picture,” the science chief said. “If we could locate the books that are supposed to exist–”

“The constant rumor is,” security said, “that the hillers have them. If they exist.”

“We don’t press the hillers. They’ll run on us.”

“If there are literates among the hillers, and books, Union materials–”

“We do what we can,” the mission chief said. “Short of a search, which might drive the material completely underground.”

“We know what the colony was. We know that the calibans moved in on them. Something we did scared them off right enough. Maybe it was the noise of the shuttle. But somewhere the first colony lost control, and cleared out of this place. Went to the hills. The azi stayed in the town. The Dean line, a couple of others trace back to the colonists; but there’s a hiller line among traders from one Elly Flanahan, and a lot of Rogerses and Innises and names that persist that aren’t like azi names. Somethingturned most of the colonists to the hills, completely away from this site. The azi tended to stay, being azi. The flood hypothesis is out. Policy split is possible…but there’s not much likelihood of it. The old camp seemed to have been purposely stripped, just people moving out. And calibans all over it. Tunnelled all under it. The earthmovers sunk and near buried. That’s caliban damage, that’s all.”

“We have a pretty good picture,” science said. “It’s far from complete. If there are records–if there was anything left but anomalies like this boy Dean–”

“We pull the town tighter in,” the mission chief said. “We continue the program, while we have the chance.”

“Only with the town itself.”

“Militarily–” security said, “the only answer. We can’t get the hillers. Not without the town at a more secure level than it is. We can’t ferret the hillers out. Can’t.”

“There’s division of opinion on that.”

“I’m telling you the departmental consensus. I’m telling you the longrange estimate. We don’t need hardened enemies on this world. We don’t use the fist.”

“The policy stands,” the mission chief intervened, a calm voice and firm. “The town first. We can’t reach into the hiller settlement.”

“The calibans–”

“We just keep an eye on that movement. If the caliban drift in our direction accelerates, then we take alarm.”

“The drift is there,” science said. “The mounds exist, a kilometer closer than last season.”

“Killy has a breeding cycle theory that makes a great deal of sense–that this advance and retreat has something to do with a dieoff–”

“We make theories at a distance. While the ban holds on firsthand observation–”

“We do what we can with the town,” the mission chief said, “before we take any action with the calibans. We don’t move until we’re absolutely secure.”

xii

Year 89, day 203 CR

Styxside

They were born‑men and townsmen and they came up the river with a great deal of noise, a sound of hardsoled boots and breaking of branches and sometimes splashing where a stream fed into the Styx. Jin was amazed and squatted on a rock to see, because there had never in his lifetime come such a thing, people from inside the barrier come from behind their fences and down the Styx.

They saw him there, and some of them aimed their guns from fright. Jin’s heart froze in him from shock and he moved no muscle until the seniormost of them waved the guns away and stopped the rest of the column in the kind of order townsmen liked.

“You,” the man said. “Hiller?”

Jin nodded, squatting on his rock, his eyes still alert for small movements of weapons. He had his arms about his leatherclad knees, but there was brush beside him and he could bound away with one fast spring if they went on being crazy.

“You got your number, hiller?”

Jin made a pursing of his lips, his eyes very much alert. “Got no number, born‑man. I hunt. I don’t trade behind your wire.”

The man came a little closer, looking up at him on his rock. “We’re not behind the wire now. Don’t need a number. Want to trade?”

“Trade what?”

“You know calibans, hiller?”

Jin half‑lidded his eyes. “O, so, calibans. Don’t touch them, born‑man. The old browns, they don’t take much to hunters. Or strangers come walking ’long the Styx.”

“We’re here to study,” another man said, leaving the others to come closer. He was an older man with gray hair. “To learn the calibans. Not to hunt.”

“Huh.” Jin laughed hiller‑fashion, short and soft. “The old browns don’t fancy being learned. You make tapes, old born‑man, you make tapes to teach you calibans? They go away from you, long time ago. Now you want them back? They make your buildings fall, they drag you under, old born‑man, take you down with them, down in the dark under ground.”

“I’ll go up there,” a young man said; but: “No,” the old man said. “He’s all right. I want to hear him.–Hiller, what’s your name?”

“Jin. What’s yours?”

“Spencer. You mind if I come up there?”

“Sir–” the man said, with the weapons. But the old man was coming up the side of the rocky slope, and Jin considered it and let him, amused as the old born‑man squatted down hiller‑fashion facing him.

“You know a lot about them,” Spencer said.

Jin shrugged, not displeased at respect.

“You hunt them?” Spencer asked. “You wear their hides.”

“Grays,” Jin said, rubbing his leather‑clad knee. “Not the browns.”

“What’s the difference?”

It was a stupid question. Jin studied the old man, conceived an outrageous idea, because it was a pleasant old face, a comfortable face, on this slightly fat man with wrinkled skin and fine cloth clothes. Fat was prosperity, just enough. An important man who climbed up a rock and sat with a young hunter. Jin grinned, waved a dismissing hand. “You tell the rest of them go home. They make too much noise. I take you upriver.”

“I can’t do that.”

“Make the calibans mad, that noise. You want to see, I show you.”

Ah, the old man wanted the bargain. He saw it in the eyes, pale, pale blue, the palest most wonderful blue he ever saw. And the old man got down off his rock and went to the armed young leader and argued, in harder and harder words.

“You can’t do that,” the young man said.

“You turn them around,” the old one said, “and you report how it was.”

In the end they each got half, because the old man was going on and the rest were waiting here.

“Not far,” Jin said easily. He bounced down off his rock, a soft landing on softsoled boots, and straightened with a nod to the old man in the way that they should go.

“He hasn’t made a deal,” the armed man said. “Dr. Spencer, he’s no townsman; we’ve got no number on him.”

“Maybe if you had,” Spencer said, “he wouldn’t be any good out here.”

The armed man said nothing. Jin motioned to the old one. It was a lark. He was fascinated by these people he had never seen so close at hand, in their fine cloth and hard boots. He reckoned this man for someone–not just a townsman but from the buildings where no one got, not even town folk, and least of all hillers.

And never a hunter who had no number on his hand, for passing the fences and going and coming into the born‑man territory.

“Come on,” he said to the old man Spencer. “You give me a shirt, all right?” He knew that such folk must be rich. “I show you calibans.”

The old man came with him, walking splayfooted down the bank, shifting the straps of all sorts of things he carried. Flitters dived and splashed among the reeds and the old man puffed on, making noise even in walking, a helpless sort in the way no hiller child was helpless.

I could rob this man, Jin thought, just because robbery did happen, high in the hills; but it was a kind of thought that came just because he thought it was trusting of the old man to be carrying all that wealth and going off with a stranger who was stronger and quicker and knew the land, and he was wondering whether the old man knew people robbed each other, or whether inside the camp such things never happened.

He found the calibans where he knew to find them, not so very far as they had been a hand of years ago. Even ariels were more plentiful, a lacery of trails across the sandy margin. Ariels, grays, even browns had turned up hereabouts, and all the lesser sorts, the hangers‑about: it was a rich season, a fat season.

“Look,” he said and pointed, showing the old man a ripple amid the Styx, where the broad marshy water reflected back the trees and the cloudy sky.

The old man stopped and gaped, trying to make out calibans; but there was no seeing that one clearly. It was fishing, and need not come up. They kept walking around the next bank, where mounds rose up on all sides of them, and trees thrust their roots in to drink from the dark hollows. It was forest now, and only leaves rustled.

“They’re all about us,” he told the man, and the man started violently and batted at a flitter which chanced at that moment to land on his neck. The startlement made Jin laugh. “Listen,” Jin said, and squatted down, so the old man squatted too, and paid attention when he pointed across the water, among the trees. “Over there–across the water–that’s theirs. That’s theirs all the way to the salt water, as far as a man can walk. They’re smart, those calibans.”

“Some of you–live in there. I’ve heard so. Could I talk with one?”

Jin’s skin prickled up. He looked toward the safe side of the river, toward familiar things. “Tell you something, old born‑man. You don’t talk to them. You don’t talk about them.”

“Bad people?”

Jin shrugged, not wanting to discuss it. “Want a caliban? I can whistle one.”

“They’re dangerous, aren’t they?”

“So’s everyone. Want one?” He did not wait, but gave out a low warble, knowing what it would do.

And very quickly, because he knew a guard had been watching all this tramping about near the mound, a caliban put its head up out of the brushy entrance and a good deal more of the caliban followed.

He heard a tiny sound by him, a whirring kind of thing. He shot out a hand at the machinery the man carried. “Don’t do that. Don’t make sounds.”

It stopped at once. “They pick that up.”

“You just don’t make sounds.”

“It’s big”

Children said that, when they first saw the old browns. Jin pursed his lips again, amused. “Seen enough, old born‑man. Beyond here’s his. And no arguing that.”

“But the ones–the humans–that go inside–Is it wrong to talk about that? Do you trade with them?”

He shook his head ever so slightly. “They live, that’s all. Eat fish.” Above them on the ridge the caliban raised its crest, flicked out a tongue. That was enough. “Time to move, born‑man.”

“That’s a threat.”

“No. That’s wanting.” He heard something, knew with his ears what it was coming up in the brush, grabbed the born‑man’s sleeve to take him away.

But the Weird crouched there, all long‑haired and smeared with mud, head and shoulders above the brush.

And the born‑man refused to move.

“Come on,” Jin said urgently. “Come on.” Out of the tail of his eye, in the river, a ripple was making its way toward them. The man made his machinery work once more, briefly. “There’s another one. There’s too many, born‑man. Let’s move.”

He was relieved when the man lurched to his feet and came with him. Very quietly they hurried out of the place, but the old man turned and looked back when the splash announced the arrival of the swimmer on the shore.

“Would they attack?” the born‑man asked.

“Sometimes they do and sometimes not.”

“The man back there–”

“They’re trouble, is all. Sometimes they’re trouble.”

The old man panted a little, making better speed with all his load.

“What do you want with calibans?” Jin asked.

“Curious,” the old man said. He made good time, the two of them going along at the same pace. “That’s following us.”

Jin tracked the old man’s glance at the river, saw the ripples. “That’s so.”

“I can hurry,” the old man offered.

“Not wise. Just walk.”

He kept an eye to it–and knowing calibans, to the woods as well. He imagined small sounds…or perhaps did not imagine them. But they ceased when they had come close to the curve of the river where the rest of the born‑men waited.

They were nervous. They got up from sitting on their baggage and had their guns in their hands. Out in the river the ripples stopped, beyond the reeds, in the deep part.

“They’re there,” the old man said to the one in charge of the others. “Got some data. They’re stirred up some. Let’s be walking back.”

“Got a shirt owed me,” Jin reminded them, hands on hips, standing easy. But he reckoned not to be cheated.

“Hobbs.” The old man turned to the younger, and there was some ado while one of the men took off his shirt and passed it over. The old man gave it to Jin, who looked it over and found it sound enough. “Jin, I might like to talk with you. Might like you to come to the town and talk.”

“Ah.” Jin tucked his shirt under his arm and backed off. “You don’t put any mark on me, no, you don’t, born‑man.”

“Get you a special kind of paper so you can come and go through the gates. No number on you. I promise. You know a lot, Jin. You’d find it worth your time. Not just one shirt. Real pay, town scale.”

He stopped backing, thinking on that.

And just then a splash and a brown came up through the reeds, water sliding off its pebbly hide. It came up all the way on its legs.

Someone shot. It lurched and hissed and came–“No!” Jin yelled at them, running, which was the wise thing. But they shot with the guns, and it hissed and whirled and flattened reeds in its entry into the river. The ripples spread and vanished in the sluggish current. It went deep. Jin crouched on his rock and hugged himself with a dire cold feeling at his gut. There was shouting among the folk. The old man shouted at the younger and the younger at the others, but there was a great quiet in the world.

“It was a brown,”Jin said. The old man looked up at him, looking as if he of all of them halfway understood. “Go away now,” Jin said. “Go away fast.”

“I want to talk with you.”

“I’ll come to your gate, old born‑man. When I want. Go away.”

“Look,” the younger man said, “if we–”

“Let’s go,” the old man said, and there was authority in his voice. The folk with guns gathered up all that was theirs and went away down the shore. The bent place stayed in the reeds, and Jin watched until they had gone out of sight around the bend, until the bank was whole again. A sweat gathered on his body. He stared at the gray light on the Styx, trying to see ripples, hoping for them.

But brush whispered. He stood up slowly, on his rock, faced in the direction of the sound.

Two of the Weirds stood there, with the rags of garments that Weirds affected, their deathly pale skins streaked with mud about hands and knees. Their backs were to the upriver. Their shadowed eyes rested on him, and he grew very cold, reckoning he was about to die. There was nowhere to run but the born‑men’s wire. The hiller village could never hide him; and he would die of other reasons if he was shut away behind the wire and numbered.

One Weird lifted his head only slightly, a gesture he took for a summons. He might cause them trouble. He was minded to. But somewhere, not so far away and not in sight either, would be another of them, or two or three. They would move if he denied them. So he leapt down from his rock and came closer to the Weirds as they seemed to want.

They parted, opening a way for him to go, and a quiet panic settled into him, because he understood then that they intended to bring him back with them upriver. Desperately he looked leftward, toward the Styx, toward the gray sunlight mirrored among the reeds, hoping against all expectation that the brown the born‑men had shot would surface.

No. It was gone–dead, hurt, no one might know. A gentle hand took his elbow, ever so gently tugging at him, directing him where he had to go if he had any hope to live.

He went, retracing the track he and the old man had followed, and now the Weirds held him by either arm. The one on his left deftly reached and relieved him of his belt knife.

He could not understand–how they moved him, or why he did not break and run; only the death about him was instant and what was ahead was indefinite, holding some small chance. There was no reckoning with the Weirds or with the browns. There was no understanding. They might bring him back to the mounds and then as capriciously let him go.

The turns of the Styx unwound themselves until the sky‑shining sheet was dimmed in the shade of trees, until they reached the towering ridges and the tracks he and the old man had made when they had stopped.

Perhaps they would hold him here and the old brown would come out and eye him as calibans would, and lose interest as calibans would, and they would let him go.

No. They urged him up the slope of the mound, toward the dark entryway in the side of it, and he refused, bolted suddenly out of their hands and down among the brush at the right, breaking twigs and thorns on his leather clothing, shielding his face with his arms.

A hiss broke in front of him and the head of a great brown loomed up, jaws gaping. He skidded to a stop, slapped instinctively at a sharp sting on his cheek and felt a dart fall from under his fingers. The brown in front of him turned its head to regard him with one round golden eye while he felt that side of his face numb, his heart speeding. His extremities lost feeling, his knees buckled: he flung up an arm to protect his eyes as brush came up at him, and lacked the strength to move when he landed among the thorny branches. They were all about him, the human shapes, silent. Gentle hands tugged at him, turning him onto his back, so that a lacery of cloudy sky and branches swung into his vision.

He was not dying. He was numb, so that they could gather him up and carry him but he was not dead when they carried him toward the hole in the earth, and realizing this, he tried to fight, in a terror deeper than all his nightmares. But he could not move, not the least twitch of a finger, not even to close his eyes when dirt fell into his face, not to close his mouth or swallow or use his tongue, even to cry out when the dark went around him and he was alone with them, with their silence and their touches.

xiii

Year 89, day 208 CR

Main Base

“No sign of this hiller,” Spencer said.

“No, sir,” Dean said, hands behind him.

Spencer frowned, turned from his table fully facing Dean–an intense young man, his assistant, with a shock of thick black hair and a coppery skin tone and a faded blue number on his hand that meant townsman, at least intermittently. Presently Dean was doing field work, meaning he was back in the town again. “How did you hunt for him?” Spencer asked.

“Asking other hillers. Those who come to trade. Theyhaven’t seen him.”

“They know him?”

Dean took the liberty and sat down on the other stool at the slanted desk full of reports, pulled it under him. He smelled of recent soap, never of the fields. Meticulous in that. He had ambitions, Spencer reckoned. He was good–in what they let him do. “Name’s known, yes. There’s a kind of split–I don’t pick up all of it; I’ve given you notes on that. At any rate, there was this very old azi–You want his history?”

“Might be pertinent.”

“The last azi survivor. His brood went for the hills. That’s the ancestry. You hearabout that line, but you don’t see them. None of them are registered to come into the camp. There’s an order among hillers. The ones we get around here–they’ll talk easy on some things. But I didn’t get an easy feeling asking about this fellow Jin.”

“How–not easy?”

A shrug. “Like first it was no townsman’s business; like second, that maybe this particular hiller wouldn’t be dealing with a townsman.”

“How did you put it to them?”

“Just that I had come on something that had to do with this Jin. I thought it was clever. After all, his ancestor was hereabouts. And it used to be that townsmen would trade found‑things to the hills. I didn’t say anything more than that. They might get curious. But if this man’s a bush hiller, it could be a while.”

“Meaning he might be out of their settlement and out of touch.”

“Meaning that, likely. It seemed to be a good bit of gossip. I imagine it’ll go on quick feet. But no news yet.–You mind if I ask what I’m looking for?”

Spencer clamped his lips together, thinking on it, reached then and dragged a set of pictures down from the clutter on the desk, arranged them in front of Dean.

“That’s the Styx.”

“I see that,” Dean said.

Spencer frowned and livened the wallscreen, played the tapeloop that was loaded in the machine. He had seen the tape a score of times, studied it frame by frame. Now he watched Dean’s face instead, saw Dean’s face go rigid in the light of the screen, seeing the caliban and then the human come out of the mound. Dean’s whole body gave back, hands on the edge of the tabletop.

“Bother you?”

Dean looked toward him as the tape looped round again. Spencer cut the machine off. Dean straightened with a certain nonchalance. “Not particularly. Calibans. But someone got real close to do that tape.”

“Not so far upriver. Look at the orbiting survey.”

Spencer marked the place, difficult to detect under the general canopy of trees. Dean looked, looked up, without the nonchalance. “This have to do with the hiller you’re looking for, by any chance?”

“It might.”

“You take these?”

“You’re full of questions.”

“That’s where you and the soldiers went. Upriver last week. Looking for calibans.”

“Might be.”

“This hunter–this Jin–He was there? He guided you?”

“You don’t like the sound of it.”

Dean bit at his lip. “Not a good idea to go up on calibans like that. Not a good idea at all.”

“Let me show you something else.” Spencer pulled a tide of pictures down the slope of the desk. “Try those.”

Dean turned and sorted through them, frowning.

“You know what you’re looking at?”

“The world,” Dean said. “Seen from orbit.”

“Pictures of what?”

A long silence, a shuffling of pictures. “Rivers. Rivers all over the world. I don’t know their names. And the Styx.”

“And?”

A long silence. Dean did not look around.

“Caliban patterns,” Spencer said. “You see them?”

“Yes.”

“Want to show you something more.” Spencer found the aerial shot of the hiller village, thatched huts and stone walls, winding walls, walls that bent and curved. He put a shot of the Base and town and fields next to it, a checkerboard geometry. “Don’t you find something remarkable in that? Have you ever seen it?”

Dean sat still, his eyes only on the pictures under his hands. “I think any townsman would tend to understand that.”

“How do you mean?”

“The founders laid out the town streets. Hillers made the hiller village.”

“Why didn’t they make it like the town?”

“Because they don’t like to do things like us. Spirals are like them. Maybe they got it from the calibans. I figure they did. They do spirals sometimes–like in the dust. You talk with them to trade–they squat down and draw when they don’t like much what you’re telling them.”

“I don’t think I’ve ever seen a hiller do that.”

“Wouldn’t.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“Like when you send me out to ask things hillers won’t say when you ask it. Like when a hiller’s dealing with somebody in Base clothes it’s one way; and when it’s a townsman that hiller’s more and less hard to deal with. They price you way high if they think they can; but they don’t give you the eye, they don’t do hiller tricks when they bargain. Like spitting in the dirt. Like looking off. Like writing patterns.”

“Patterns. What patterns?”

“Spirals. Like two of them squatting down in the dirt and letting the dust run out of their hands or drawing with their fingers–one does one thing and one does a bit on it, while they’re thinking over a deal. And they make you think they’ve forgotten you’re standing there. But maybe they’re talking to each other that way. Maybe it’s nothing at all. That’s why they do it. Because we won’t know. And we’re supposed to wonder.”

Spencer sat and stared at him so long that Dean finally looked his way. “Somehow that never got into your reports.”

“I never thought it was much. It’s all show.”

“Is it?” Spencer pulled two more pictures from the lot, one of an eastern hemisphere river, one of the north shore, a mosaic going toward the sea, including all the effluence of the Styx, and the Base and both town and hiller settlement. He pointed out the places, the encroachment of calibans toward the sea on the far side of the river, the faint shadowing at the end of ridges. “They’re different. The spirals of calibans everywhere in the world but here–are looser. They don’t make hills. See the shadow cast from the centers, here, here and here–that’s a tall structure. That’s a peak in the center of those spirals. Let me get you a closeup.” He searched and pulled another out, that showed the structure, a spiral winding into a miniature mountain, slid that in front of Dean. “You understand what I’m saying now? Only here. Only across from the Base. Is that a caliban structure?”

“How big is that?”

“The complex is a kilometer wide. The peak is forty meters wide at base of the most extreme slope and twenty high. Have you ever seen the like?”

Dean shook his head. “No.” He glanced up. “But then I’ve never seen a caliban. Except the pictures.”

“They didn’t like sharing the Base. They moved out.”

“But they’re moving back. On the river. Your pictures–You won’t get that hunter to go across the Styx, if that’s what you’re thinking. I don’t think you will. I don’t think you ought to push at the hillers where it regards calibans.”

“Why?”

A shrug. “I just don’t think you should.”

“That’s not the kind of answer you draw your pay for.”

“I think it’s dangerous. I think the hillers could get anxious. The calibans are already close. They won’t like them stirred up, that’s what.”

“They hunt them?”

Another shrug. “They trade in leather. But there’s calibans and calibans. Different types.”

“The browns.”

“The browns and the grays.”

“What’s the difference?”

A third shrug. “Hillers hunt grays. They know.”

“Know what?”

“Whatever they know. I don’t.”

“There was this caliban,” Spencer said carefully. “We’d been up to the mound to take those pictures, this Jin and I. Alone. And we got back to the troops, and this caliban came out of the river. They shot it and it slid back in. ‘It was a brown,’ the hunter said. Like that. And then: ‘Go away fast.’ What do you make of that?”

Dean just stared a moment, dead‑faced the way he would when something bothered him. “Did you?”

“We left.”

“I reckon he did, too. Fast and far as he could. Hewon’t come to your gate, no.”

“Meaning?”

“Meaning he’s going to be scared a long, long time. He’ll never come to you.”

“Would he be that afraid?”

“He’d be that afraid.”

“Of what? Of calibans? Or Weirds?”

A blink of the dark eyes. “Whatever’s worth being afraid of. Hillers would know. I don’t. But don’t go out there. Don’t send the soldiers outside the wire, not another time.”

“I’m afraid I don’t make that decision.”

“ Tell them.”

“I’ll do that,” Spencer said frowning. “You don’t think the search is worthwhile, do you?”

“You won’t find him.”

“Keep your ears open.”

“I’d thought about sleeping in my own quarters tonight.”

“I’d rather you stayed in the town–just keep listening.”

“For what?”

“Hiller talk. All of it. What if I offered you a bonus–to go outside the wire?”

Dean shook his head warily. “No. I don’t do that.”

“Townsmen have gone to the hills before.”

“No.”

“Meaning you won’t. Suppose we put a high priority on that.”

Dean sat very still. “Townsmen know I’m from inside. Hillers may be stirred up right now. And if they are, and if they knew where I came from–”

“You mean you think they’d kill you.”

“I don’t know what they’d do.”

“All right, we’ll think about that. Just go back to the town and listen where you can.”

“All right.” Dean got up, walked as far as the door, looked back. He looked as if he would like to say something more, but walked away.

Spencer stared at his pictures, ran the loop again.

Calibans had tried the wire last night down by the river. They had never done that, not since Alliance came to the world.

There had to be precautions.

xiv

Year 89, day 208 CR

Styxside

He might be mad: or he wished he were, in the dark, in the silence broken only by slitherings and breathings and sometimes, when his sanity had had all it could bear, by his screams and sobs. His screaming could drive them back a while, but they would be back.