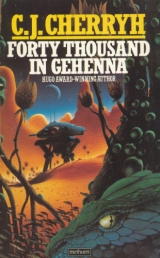

Текст книги "Forty Thousand in Gehenna"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

It was healing, she reckoned. By spring it would be well. A little discomfort was only natural.

But the scar went red and the place went hot and finally she could not help but limp.

So the nurses noticed; and they brought old Karel to look at it. And Karel got out his knives.

They gave her bitterweed boiled up to kill the pain, but the tea made her sick at her stomach and left her only doubly miserable. She clamped her jaws and never yelled, only a scant moaning while old Karel hunted away in the wound he had made; and the sweat went cold on her. “Let me go,” she said to the riders who had come to help Karel hold her still; and mostly they did, except when the knife went deep and the sweat broke out on her and she threw up.

Karel held up a bit of something like a small bone. Her mother Ellai came to see.

“Seafolk spine,” Karel said. “Left in the wound. Whoever wrapped that leg up, never looked to see. Never should have left it that way.”

He laid the spine aside and went back to his digging with the knife; they gave her more tea and she threw that up too, the several times they gave it to her.

Afterwards her mother only looked at her, as she lay limp and buried in blankets. Scar was somewhere down below, with Weirds to keep him quiet; only Twig was in the room, and her mother just stood there staring at her, whatever went on behind her eyes, whether that her mother was thinking she was less threat now, whether she just despised the intelligence of the daughter she had birthed.

“So your starman knows everything,” her mother said.

Elai just stared back.

xii

189 CR, day 24

Message, R. Genley to Base Director

Weather has made observation difficult. Persistent fogs have obscured the riverside now and we have only limited view.

Last night the calibans came close. We could hear them moving around the shelter. When we went outside they retreated. We are using all due caution.

xiii

189 CR, day 24

The Base Director’s office

“Genley,” McGee said, “is in danger. I would remind you, sir, the Base has fallen before. And there were warnings of it. Take the calibans seriously.”

“They’re far from Base, Dr. McGee.” The Director leaned back, arms locked across his middle. The windows looked out on the concrete buildings, on fog. “But this time I do agree with you. There’s a possibility of a problem out there.”

“There’s more than a possibility. The rainy season seems to act on the calibans, and everything’s stirred up on Styxside.”

“What about your assessment of the calibans as a culture? Doesn’t this weather‑triggered behavior belong to something more primitive?”

“Do we sunbathe in winter?”

“We’re talking about aggression.”

“Early humans preferred summer for their wars.”

“Then what does this season do for calibans?”

“I wouldn’t venture an answer. We can only observe that it docs something.”

“Genley’s aware of the problem.”

“Not of the hazards. He won’t listen to those.”

The Director thought a moment. “We’ll take that under advisement. We know where you stand.”

“My request–”

“Also under advisement.”

xiv

189 CR, day 25

R. Genley to Base Director.

…I have made a contact. A band of Stygians riding calibans has shown up facing our camp oh our own side of the Styx this foggy morning. There was no furtiveness in their approach. They stopped a moment and observed us, then retreated and camped nearby. Mist makes observation difficult, but we can see them faintly at present.

189 CR, day 25

Base Director to R. Genley

Proceed with caution. Weather forecast indicates clearing tonight and tomorrow, winds SW/10‑15.

Drs. McGee, Mannin, and Galliano are on their way afoot to reach your position with 10 security personnel. Please extend all professional cooperation and courtesy. Use your discretion regarding face to face contact.

xv

189 CR, day 26

Styxside Base

They reached the camp by morning, staggering‑tired and glad enough of the breakfast they walked in on, with hot tea and biscuits.

“Hardly necessary for you to trek out here,” Genley said to McGee. He was a huge florid‑faced man, solid, monument‑like in the khaki coldsuit that was the uniform out here. McGee filled out her own with deskbound weight‑gain. Her legs ached and her sides hurt. The smell of the Styx came to them here, got into everything, odor of reeds and mud and wet and cold, permeating even the biscuits and the coffee. It was freedom. She savored it, ignoring Genley.

“I expect,” Genley went on, “that you’ll follow our lead out here. The last thing we need is interference.”

“I only give advice,” she said, deliberately bland. “Don’t worry about your credit on the report.”

“I think they’re stirring about out there,” said Mannin from the doorway. “They had to have seen us come in.”

“Weather report’s wrong as usual,” Genley said. “Fog’s not going to clear.”

“I think we’d better get out there,” McGee said.

“Have your breakfast,” Genley said. “We’ll see to it.”

McGee frowned, stuffed her mouth, washed the biscuit down, and trailed him out the door.

The sun made an attempt at breaking through the mist. It was all pinks and golds, with black reeds thrusting up in clumps of spiky shadow and the fog lying on the Styx like a dawn‑tinted blanket.

Every surface was wet. Standing or crouching, one felt one’s boots begin to sink. Moisture gathered on hair and face and intensified the chill. But they stood, a little out from their camp, facing the Stygians’ camp, the humped shapes of calibans moving restlessly in the dawn.

Then human figures appeared among the calibans.

“They’re coming,” McGee said.

“We just stand,” said Genley, “and see what they do.”

The Stygians drew closer, afoot, more distinct in the morning mist. The calibans walked behind them, like a living wall, five, six of them.

Closer and closer.

“Let’s walk out halfway,” said Genley.

“Not sure about that,” said Mannin.

Genley walked. McGee trod after him, her eyes on the calibans as much as the humans. Mannin followed. The Security fieldmen were watching them. No one had guns. None were permitted. If they were attacked, they might die here. It was Security’s task simply to escape and report the fact.

Features became clear. There were three elder men among the Stygians, three younger, and the one foremost was youngest of the lot. His long hair was gathered back at the crown; his dark beard was cut close, his leather garments clean, ornamented with strings of river‑polished stones and bone beads. He was not so tall as some. He looked scarcely twenty. He might be a herald of some kind, McGee thought to herself, but there was something–the spring‑tension way he moved, the assurance–that said that of all the six they saw, this was the one to watch out for.

Young man. About eighteen.

“Might be Jin himself,” she said beneath her breath. “Right age. Watch it with this one.”

“Quiet,” Genley said. He crouched down, let a stone slip from his clenched hand to the mud, let fall another pebble by that one.

The Stygians stopped. The calibans crouched belly to the ground behind them, excepting the biggest, which was poised well up on its four legs.

“They’re not going to listen,” McGee said. “I’d stand up, Genley. They’re not interested.”

Genley stood, a careful straightening, his Patterning‑effort abandoned. “I’m Genley,” he said to the Stygians.

“Jin,” said the youth.

“The one who gives orders on the Styx.”

“That Jin. Yes.” The youth set his hands on hips, walked carelessly off to riverward, walked back again a few paces. The calibans had all stood up. “Genley.”

“McGee,” McGee said tautly. “He’s Mannin.”

“ MaGee. Yes.” Another few paces, not looking at them, and then a look at Genley. “This place is ours.”

“We came to meet you in it,” said Genley. “To talk.”

The young man looked about him, casually curious, walking back to his companions.

This is an insult, McGee suspected without any means to be sure. He’s provoking us. But the young face never changed.

“Jin,” McGee said aloud and deliberately, and Jin looked straight at her, his face hard. “You want something?” McGee asked.

“I have it,” Jin said, and ignored her to look at Genley and Mannin. “You want to talk. You have more questions. Ask.”

No, McGee thought, sensing that civility was the wrong tack to take with this youth. “Not interested,” she said. “Genley, Mannin. Come on.”

The others did not move. “We’ll talk,” Genley said.

McGee walked off, back to the camp. It was all she had left herself to do.

She did not look back. But Genley was hard on her heels before she had gotten to the tent.

“McGee!”

She looked about, at anger congested in Genley’s face. At anger in Mannin’s.

“He walked off, did he?” she asked.

xvi

189 CR, day 27

Main Base, the Director’s office

She expected the summons, stood there weary and dirty as she was, hands folded. She had come back to Base with three of the security personnel. She had not slept. She wanted a chair.

There was no offer. The Director stared at her hard‑eyed from behind his desk. “Botched contact,” he said. “What was it, McGee, sabotage? Could you carry it that far?”

“No, sir. I did the right thing.”

“Sit down.”

She pulled the chair over, sank down and caught her breath.

“Well?”

“He was laughing at us. At Genley. He was provoking Genley and Genley was blind to all of it. He was getting points off us.”

“The sound tape doesn’t show it. It shows rather that he knows you.”

“Maybe he does. Rumors doubtless travel.”

“And you picked this up too, of course.”

“Absolutely.”

“You lowered Genley’s credibility.”

“Genley didn’t need help in that. This Jin is dangerous.”

“Might there be some bias, McGee?”

“No. Not on my side.”

There was silence. The Director sat glaring, twisting a stylus in his hands. Behind him was the window, the concrete buildings of the Base. Safety behind the wire. Beneath them detectors protected the underground, listened for undermining. Man on Gehenna had learned.

“You’ve created a situation,” the Director said.

“In my professional judgement, sir, it had to be done. If the Styx doesn’t respect us–”

“Do you think respect has to matter, one way or another? We’re not in this for points, McGee, or personal pride.”

“I know we’ve got a mission out there on the Styx with their lives riding on that respect. I think maybe I made them doubt their calculations about us. I hope it’s good enough to keep Genley alive out there.”

“You keep assuming hostility exists.”

“Based on what the Cloudsiders think.”

“On a ten year old girl’s opinion.”

“This Jin–every move he made was a provocation. That Caliban of his, the way it was set, everything was aggression.”

“Theories, McGee.”

“I’d like to renew the Cloudside contact. Pursue it for all it’s worth.”

“The same way you turned your back on the Styxsiders?”

“It’s the same gesture, yes, sir.”

“What about your concern for the Styxside mission? Aren’t you afraid that would precipitate some trouble?”

“If Genley’s right, it won’t. If I’m right, it would send a wrong signal not to. Not doing it might signal that we’re weak. And that could equally well endanger Genley.”

“You seriously think these Styxsiders could look at this Base and think we’re without resources.”

“This base has fallen before. Despite all its resources. I think it could be a very reasonable conclusion on their part. But I wouldn’t venture to say just what they think. Their minds are at an angle to ours. And there’s the possibility that we’re not dealing just with human instinct.”

“Calibans again.”

“The Gehennans take them seriously, however the matter seems to us. I think we have to bear that in mind. The Gehennans think the Calibans have an opinion. That’s one thing I’m tolerably sure of.”

“Your proposal?”

“What I said. To take all our avenues.”

The Director frowned, leaned forward and pushed a button on the recorder.

xvii

Report from field: R. Genley

The Stygians remain, watching us as we watch them. Today there was at least a minor breakthrough: one of the Stygians approached our shelter and looked us over quite openly. When we came toward him he walked off at a leisurely pace. We reciprocated and were ignored.

xviii

Styxside

“Sit,” said Jin; and Genley did so, carefully, in the firelit circle. They took the chance, he and Mannin together–a wild chance, when one of the young Stygians had come a second time to beckon them. They walked alone into the camp, among the calibans, unarmed, and there was the waft of alcohol about the place. There were cups passed. Quickly one came their way as they settled by the fire.

Genley drank first, trying not to taste it. It was something like beer, but it numbed the mouth. He passed the wooden cup on to Mannin and looked up at Jin.

“Good,” said Jin–a figure that belonged in firelight, a figure out of human past, leather‑clad, his young face sweating in the light and smoke, his eyes shining with small firesparks. “Good. Genley. Mannin.”

“Jin.”

The face broke into a grin. The eyes danced. Jin took the cup again. “You want to talk to me.”

“Yes,” Genley said.

“On what?”

“There’s a lot of things.” Whatever was in the drink numbed the fingers. Distantly Genley was afraid. “Like what this drink is?”

“Beer,” Jin said, amused. “You think something else, Gen‑ley?” He drank from the same cup, and the next man filled it again. They were all men, twelve of them, all told. Three fiftyish. Most young, but none so young as Jin. “Could be bluefish in a cup. You die that way. But you walk in here, you bring no guns.”

“The Base wants to talk. About a lot of things.”

“What do you pay?”

“Maybe it’s just good for everyone, that you and the Base know each other.”

“Maybe it’s not.”

“We’ve been here a long time,” Mannin said, “living next to each other.”

“Yes,” said Jin.

“Things look a lot better for the Styx recently.”

Jin’s shoulders straightened. He looked at Mannin, at them both, with appraising eyes. “Watch us, do you?”

“Why not?” Genley asked.

“I speak for the Styx,” Jin said.

“We’d like to come and go in safety,” Genley said.

“Where?”

“Around the river. To talk to your people. To be friends.”

Jin thought this over. Perhaps, Genley thought, sweating, the whole line of approach had been wrong.

“Friends,” Jin said, seeming to taste the word. He looked at them askance. “With starmen.” He held out his hand for the cup, a line between his brows as he studied them. “We talk about talking,” Jin said.

189 CR, day 30

Message, R. Genley to Base Director

I have finally secured a face to face meeting with the Stygians. After consistently refusing all approach since the incident with Dr. McGee, Jin has permitted the entry of Dr. Mannin and myself into his camp. Apparently their pride has been salved by this prolonged silence and by our approach to them.

Finding no further cause for offense, they were hospitable and offered us food and drink. The young Stygian leader, while reserved and maintaining an attitude of dignity, began to show both humor and ease in our presence, altogether different than the difficult encounter of four days ago.

I would strongly urge, with no professional criticism implied, that Dr. McGee avoid contact with the Styxsiders in any capacity. The name McGee is known to them, and disliked, which evidences, perhaps, both contact between Styx and Cloud, and possibly some hostility, but I take nothing for granted.

xix

189 CR, day 35

Cloud Towers

There was surprisingly little difficulty getting to the Towers of the Cloud. There looked to be, even more surprising, only slightly more difficulty walking among them.

McGee came alone, in the dawning, with only the recorder secreted on her person and her kit slung from her shoulder, from the landing she had made upriver. She was afraid, with a different kind of fear than Jin had roused in her. This fear had something of embarrassment, of shame, remembering Elai, who would not, perhaps, understand. And now she did not know any other way but simply to walk until that walking drew some reaction.

There would be a caliban, she had hoped, on this rare clear winter day: a girl on a Caliban would come to meet her, frowning at her a bit at first, but forgiving her MaGee for her lapse of courtesy.

But none had come.

Now before her loomed the great bulk of the Towers themselves, clustered together in their improbable size. City, one had to think. A city of earth and tile, slantwalled, irregular towers the color of the earth, spirals that began in a maze of mounds.

She knew First Tower, nearest the river: so Elai had said. She passed the lower mounds, through eerie quiet, past folk who refused to notice her. She passed the windowed mounds of ordinary dwellings, children playing with ariels, calibans lazing in the sun, potters and woodworkers about their business in sunlit niches in the mounds, sheltered from the slight nip of the wind, walked to the very door of First Tower itself.

A trio of calibans kept the inner hall. Her heart froze when they got up on their legs and made a circle about her, when one of them investigated her with a blunt shove of its nose and flicked a thick tongue at her face.

But that one left then, and the others did, scrambling up the entry into the Tower.

She was not certain it was prudent to follow, but she hitched up her kit strap and ventured it, into a cool earthen corridor clawed and worn along the floor and walls by generations of caliban bodies. Dark–quite dark, as if this was a way the Cloudsiders went on touch alone. Only now and again was there a touch of light from some tiny shaft piercing the walls and coming through some depth of the earthen construction. It was a place for atavistic fears, bogies, creatures in the dark. The Cloudsiders called it home.

In the dim light from such a shaft a human shape appeared, around the dark winding of the core. McGee stopped. Abruptly.

“To see Ellai,” she said when she got her breath.

The shadow just turned and walked up the incline and around the turn. McGee sucked in another breath and decided to try following.

She heard the man ahead of her, or something ahead, heard slitherings too, and pressed herself once against the wall as something rather smallish and in a hurry came bolting past her in the dark. Turn after turn she went up following her guide, sometimes now past doorways that offered momentary sunlight and cast a little detail about her guide: sometimes there were occupants in the huge rooms inside the sunless core, on which doors opened, flinging lamplight out. In some of them were calibans, in others knots of humans, strangely like the calibans themselves in the stillness with which they turned their heads her way. She heard wafts of childish voices, or adult, that let her know ordinary life went on in this strangeness.

And then the spiral, which had grown tighter and tighter, opened out on a vast sunpierced hall, a hall that astounded with its size, its ceiling supported by crazy‑angled buttresses of earth. She had come up in the center of its floor, where a half a hundred humans and at least as many calibans waited, as if they had been about some other business, or as if they had known she was coming–they had seenher, she realized suddenly, chagrined. There might easily be lookouts on the tower height and they must have seen her coming for at least an hour.

The gathering grew quiet, organized itself so that there was an open space between herself and a certain frowning woman who studied her and then sat down on a substantial wooden chair. A caliban settled possessively about it, embracing the chairlegs with the curve of body and tail and lifting its head to the woman’s hand.

Then McGee saw a face she knew, at the right against the wall, a girl who was grave and frowning, a huge caliban with a raking scar down its side. A moment McGee stared, being sure. The child’s face was hard, offering her no recognition, nothing.

She glanced quickly back to the other, the woman. “My name is McGee,” she said.

“Ellai,” said the woman; but that much she had guessed.

“I’m here,” McGee said then, because a girl had taught her to talk directly, abruptly, in a passable Cloud‑side accent, “–because the Styx‑siders have come to talk to us; and because the Base thinks we shouldn’t be talking to Styx‑siders without talking to Cloud‑side too.”

“What do you have to say?”

“I’d rather listen.”

Ellai nodded slowly, her fingers trailing over the back of her caliban. “You’ll answer,” Ellai said. “How is that boy on Styx‑side?”

McGee bit her lip. “I don’t think he’s a boy any longer. People follow him.”

“This tower near your doors. You let it be.”

“We don’t find it comfortable. But it’s not our habit to interfere outside the wire.”

“Then you’re stupid,” Ellai said.

“We don’t interfere on Cloud‑side either.”

It might have scored a point. Or lost one. Ellai’s face gave no hints. “What are you doing here?”

“We don’t intend to have a ring of Styx towers cutting us off from any possible contact with you. If we encourage you to build closer towers, it could mean more fighting and we don’t want that either.”

“If you don’t intend to interfere with anyone, how do you plan to stop the Styx‑siders building towers?”

“By coming and going in this direction, by making it clear to them that this is a way we go and that we don’t intend to be stopped.”

Ellai thought that over, clearly. “What good are you?”

“We give the Styx‑siders something else to think about.”

Ellai frowned, then waved her hand. “Then go do that,” she said.

There was a stirring among the gathering, an ominous shifting, a flicking and settling of caliban collars and a pricking‑up of the Caliban’s beside Ellai.

“So,” said McGee, uneasy in this shifting and uncertain whether it was good or ill, “if we come and go and you do the same, it ought to make it clear that we plan to keep this way open.”

An aged bald man came and squatted by Ellai’s side, put his spidery fingers on the caliban. Ellai never looked at him.

“You will go now,” Ellai said, staring at McGee. “You will not come here again.”

McGee’s heart speeded. She felt ruin happening, all her careful constructions. She kept distress from her face. “So the Styxsiders will say what they like and build where they like and you aren’t interested to stop it.”

“Go.”

Others had moved, others of the peculiar sort gathering about Ellai, crouched in the shadows. Calibans shifted. An ariel skittered across the floor and whipped into the caliban gathering. Of the sane‑looking humans there seemed very few: the woman nearest Ellai’s chair, a leather‑clad, hard‑faced type; a handful of men of the same stamp, among their gathering of dragons, among lamp‑like eyes and spiny crests. The eyes were little different, the humans and the dragons–cold and mad.

A smaller, gray caliban serpentined its way to the clear center of the floor with a stone in its jaws and laid it purposely on the floor. Another followed, placing a second beside it, while the first retrieved another rock. It was crazy. The craziness in the place sent a shiver over McGee’s skin, an overwhelming anxiety to be out of this tower, a remembrance that the way out was long and dark.

A third stone, parallel to the others, and a fourth, dividing her from Ellai.

“The way is open now,” Ellai said.

Go, that was again, last warning. McGee turned aside in disarray, stopped an instant looking straight at Elai, appealing to the one voice that might make a difference.

Elai’s hand was on Scar’s side. She dropped it and walked a few paces forward–walked with a limp, as if to demonstrate it. Elai was lame. Even that had gone wrong.

McGee went, through the dark spirals, out into the unfriendly sun.

xx

189 CR, day 43

Report, E. McGee

…I succeeded in direct contact; further contacts should be pursued, but cautiously…

189 CR, day 45

Memo, office of the Director to E. McGee

Your qualification of the incident as a limited success seems to this office to be unfounded optimism.

xxi

189 CR, day 114

Styxside

Genley looked about him at every step along the dusty road, taking mental notes: Mannin trod behind him, and Kim; and in front of them the rider atop his caliban, unlikely figure, their guide in this trek.

Before them the hitherside tower loomed, massive, solid in their eyes. They had seen this at distance, done long‑range photography, observed these folk as best they could. But this one was within their reach, with its fields, its outbuildings. Women labored in the sun, bare‑backed to the gentle wind, the mild sun, weeding the crops. They stopped and looked up, amazed at the apparition of starmen.

189 CR, day 134

Field Report: R. Genley

…The hitherside tower is called Parm Tower, after the man who built it. The estimates of tower population are incorrect: a great deal of it extends below, with many of the lower corridors used for sleeping. Parm Tower holds at least two thousand individuals and nearly that number of Calibans: I think about fifty are browns and the rest are grays.

The division of labor offers a working model of theories long held regarding early human development and in the degree to which Gehenna has recapitulated human patterns, offers exciting prospects for future anthropological study. One could easily imagine the ancient Euphrates, modified ziggurats, used in this case for dwellings as well as for the ancient purpose, the storage of grain above the floods and seasonal dampness of the ground.

Women have turned to agriculture and do all manner of work of this kind. Hunting, fishing, and the crafts and handcrafts, including weaving, are almost exclusively a male domain and enjoy a high status, most notably the hunters who have exclusive control of the brown Calibans. Fishers employ the grays. The grays are active in the fields as well, performing such tasks as moving dikes and letting in the water, but they are directed in this case by the class called Weirds. Weirds are both male and female, individuals who have so thoroughly identified with the calibans that they have abandoned speech and often go naked in weather too cool to make it comfortable. They do understand speech or gesture, apparently, but I have never heard one speak, although I have seen them react to hunters who speak to them. They maneuver the grays and a few browns, but the calibans do not seem to attach to them as individuals in the manner in which they attach to the hunter‑class.

Only hunters, as I have observed, own a particular caliban and give it a name. It should also be mentioned that one is born a hunter, and hunter marriages are arranged within towers after a curious polyandrous fashion: a woman marries her male relatives’ hunting comrades as a group; and her male relatives are married to their hunting comrades’ female sibs. Younger sisters usually marry outside the tower, thus minimizing inbreeding; they are aware of genetics, though, curiously enough, they have reverted to or reinvented the old term “blood” to handle the concept. There is no attempt to distinguish full brother‑sister relationship from half. In that much the system is matrilineal. But women of hunter class are ornaments, doing little labor but the making of clothes and the group care of children in which they are assisted by women relieved from field work. All important decisions are the province of the men. I have observed one exception to this rule, a woman of about fifty who seems to have outlived all her sibs and her band. She wears the leather clothing of a rider, has a caliban and carries a knife. She sits with the men at meals and has no association with the wives.

Crafts and fisher‑class women work in the fields with their daughters. Male children can strive for any class, even to be a hunter, although should a lower class male succeed in gaining a caliban he may have to fight other hunters and endure considerable harassment. There is one such individual at Parm Tower. His name is Matso. He is a fisher’s son. The women are particularly cruel to him, apparently resenting the possibility of his bringing some fisher‑sib into their society should he join a hunter‑group.

Over all of this of course is Jin himself. This is a remarkable man. Younger than most of his council, he dominates them. Not physically tall, he is still imposing because of the energy which flows from him. The calibans react to him with nervousness‑displays, a reaction in which his own plays some part: this is a beast named Thorn, which is both large and aggressive. But the most of it is due to Jin’s own force of personality. He is a persuasive speaker, eloquent, though unlettered: he is a hunter, and writing is a craft: he will not practice it.

He has survived eight years of guardianship to seize power for himself at sixteen, effectively deposing but not killing his former guardian Mes of the River Tower, from what I hear. He is inquisitive, loves verbal games, loves to get the better hand in an argument, is generous with gifts–he bestows ornaments freehandedly in the manner of some oldworld chief. He has a number of wives who are reserved to him alone but these are across the Styx. At Parm Tower he is afforded the hospitality of the hunter‑class women, which is a thing done otherwise only between two bands in payment of some very high favor. This lending of wives and the resultant uncertainty of parentage of some offspring seems to strengthen the political structure and to create strong bonds between Jin and certain of the hunter‑bands. Whether Jin lends his wives in this fashion we cannot presently ascertain.

We apparently have the freedom to come and go with the escort of one or the other hunters. Jin himself has entertained us in Parm Tower hall and given us gifts which we are hard put to reciprocate.

The people are well‑fed, well‑clothed and in all have a healthy look. Jin enumerates his plans for more fields, more towers, wider range of his hunters to the north…

Memo, E, McGee to Committee

It seems to me that it is a deceptively easy assumption that these Styxsiders are recapitulating some naturalcourse of human society. This is selective seeking‑out of evidence to fit the model Dr. Genley wishes to support. He totally ignores the contrary evidence of the Cloud Towers, who have grown up in a very different pattern.