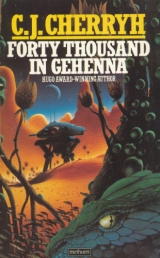

Текст книги "Forty Thousand in Gehenna"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

xviii

In the Hills

They found him in the morning, among the rocks; and Cloud raised his bow, an arrow aimed across the narrow stream–because everything had become an enemy. But the townsman, wedged with his back to the rocks, only lifted a hand as if that could stop a flint‑headed arrow and stared at them so bleakly, so wearily that Cloud lowered the bow and put the arrow away.

“Who are you?” Cloud asked when they squatted across the narrow stream from each other, while his sister Pia and his wife and son tended ma Elly, bathing her face and holding water for her to drink. “What name?”

“Name’s Dean,” the other said, hoarse, crouching there on his side with his arms about his knees and his fine town clothes in rags.

“Name’s Cloud,” Cloud said; and Dal came beside him and handed him some of the food they had brought, while the stranger sat across the stream just looking at them, not asking.

“He’s hungry,” Pia said. “We give him just a bit.”

Cloud thought about it, and finally took a morsel of bread and held it out to the townsman on his side.

The man unwound himself from his crouch and got up and waded across the stream. He took the bit they offered him and sank down again, and ate the bread very slowly. Tears started from his eyes, ran down his face, but there was never expression on it, never a real focus to his eyes.

“You come from town,” ma Elly said.

“Town’s gone,” he said.

There was none of them could think of what to say then. Town had always been, rich and powerful.

“Base buildings fell,” he said. “I saw it.”

“We go south,” Cloud said finally.

“They’ll hunt us,” Pia said.

“We go down the coast,” Cloud said, thinking through it, where the food was, where they could be sure of fresh water, streams coming to the sea.

“South is a big river,” said Dean in a quiet voice. “I know.”

They took the townsman with them. They found others as they went, some of their own kin, some that were only townsmen who had run far enough and fast enough–like themselves, those who could run, and those who would run, for whatever reason.

Others drifted to them, and sometimes calibans came, but kept their distance.

xix

Message from Gehenna Station to Alliance Headquarters

couriered by AS Winifred

“…intervention of station‑based forces has secured the perimeter of the Base. Casualties among Base personnel are fourteen fatalities and forty six injuries, nine critical… All personnel except security forces and essential staff have been lifted to the station.

“Destruction in the town is total. Casualties are undetermined. Twenty are confirmed dead, but due to the extensive damage and the hazard of the ground, further search is not presently an option. Two hundred two survivors have reached the aid stations set up at the Base gate for treatment of injuries: most told of digging themselves free. Under the cover of darkness Calibans return to the ruin and dig in the rubble. Accompanying tape #2shows this activity…

“The hiller village also suffered extensive damage and orbiting survey has seen no sign of life there. The survivors of the town and village have scattered…

“The Station will make food drops attempting to consolidate the survivors where possible… The Station urgently requests exception to the noninterference mandate for humanitarian reasons. The mission recommends lifting the survivors offworld.”

xx

Message: Alliance Headquarters Science Bureau to Gehenna Station

couriered by AS Phoenix

“…with extreme regret and full appreciation of humanitarian concern the Bureau denies request for lifting of the non‑interference mandate under any circumstance…

“Gehenna Base will be reestablished under maximum security with equipment arriving aboard this courier…

“It is Bureau policy that no interference be permitted in the territory of unconsenting sapience, even in benevolent intention…

“The Station will extend all possible cooperation and courtesy to Bureau agent Dr. K. Florio…”

xxi

Year 90, day 144 CR

Staff meeting: Gehenna Station

“It is a tragedy,” Florio said, making a fortress of his hands in front of him. He spoke quietly, eyed them all. “But those who disagree with policy have their option to be transferred.”

There was silence from the rest of the table, poses like his own, grim faces male and female. Old hands at Gehenna Station. Seniority considerable.

“We understand the rationale,” the Director said. “The reality is a little difficult to take.”

“Are they dying?” Florio asked softly. “No. The loss of life is done. The human population has stabilized. They’re surviving very efficiently down there.” He moved his hands and sorted through the survey reports. “If I lacked evidence to support the Bureau decision–it’s here. The world is put through turmoil and still two communities reassert themselves. One is well situated for observation from the Base. Both are surviving thanks to the food drops. The Bureau will sanction that much, through the winter, to maintain a viable population base. The final drop will be seed and tools. After that–”

“And those that come to the wire?”

“Have you been letting them in?”

“We’ve been delivering health care and food.”

Florio frowned, sorted through the papers. “The natives brought up here for critical treatment haven’t adjusted to Station life. Severe psychological upset. Is that humanitarian? I think it should be clear that good intentions have led to this disaster. Good intentions. I will tell you how it will be: the mission may observe without interference. There will be no program for acculturation. None. No firearms will be permitted onworld. No technological materials may be taken outside the Base perimeter except recording instruments.”

There was silence from the staff.

“There is study to be pursued here,” Florio said more softly still. “The Bureau has met measurable intelligences; it has never met an immeasurable one; it has never met a situation in which humanity is out‑competed by an adaptive species which may violate the criteria. The Bureau puts a priority on this study. The tragedy of Gehenna is not inconsiderable…but it is a double tragedy, most indubitably a tragedy in terms of human lives. For the calibans–very possibly a tragedy. Rights are in question, the rights of sapients to order their affairs under their own law, and this includes the human inhabitants, who are not directly under Alliance law. Yes, it is an ethical question. I agree. The Bureau agrees. But it extends that ethical question to ask whether law itself is not a universal concept.

“Humans and calibans may be in communication. We are very late being apprised of that possibility. Policy would have been different had we known.

“If there were any question whether humans were adapted to Gehenna, that would have to be considered–that humans may have drifted into communication with a species the behaviors of which twenty years of technologically sophisticated research and trained observation has not understood. This in itself ought to make us question our conclusions. In any question of sapience–in any definition of sapience–where do we put this communication?

“Suppose, only suppose, that humans venture into further space and meet something else that doesn’t fit our definitions. How do we deal with it? What if it’s spacefaring–and armed? The Bureau views Gehenna as a very valuable study.

“Somehow we have to talk to a human who talks to calibans. Somehow what we have here has to be incorporated into the Alliance. Not disbanded, not disassembled, not reeducated. Incorporated.”

“At the cost of lives.”

The objection came from down the table, far down the table. From Security. Florio met the stare levelly, assured of power.

“This world is on its own. We tell it nothing; we give it nothing. Not an invention, not a shred of cloth. No trade goods. Nothing. The Station will get its supplies from space. Not from Gehenna.”

“Lives,” the man said.

“A closed world,” Florio said, “gains and loses lives by its own rules. We don’t impose them. By next year all aid will have been withdrawn, food, tools, everything including medical assistance. Everything.”

There was silence after. No one had anything to say.

xxii

Year 90, day 203 CR

Cloud’s Settlement

The calibans came to the huts they made on the new river in the south, and brought terror with them.

But the shelters stood. There was no undermining. The grays arrived first, and then a tentative few browns, burrowing up along the stream.

And more and more. They fired no arrows, but huddled in their huts and tried not to hear the calibans move at night, building walls about them, closing them about, making Patterns of which they were the heart.

Calibans spared the gardens they had made. It was the village they haunted, and even by day ariels and grays sat beneath the sun.

“They have come to us,” said Elly, “the way they came to Jin.”

“We have to stay here,” said an old man. “They won’t let us go.”

It was true. They had their gardens. There was nowhere else to go.

xxiii

Settlement on Cloud’s River

“…They came from a place called Cyteen,” Dean said, by the hearth where the only light was in their common shelter, and the light shone on faces young and old who gathered to listen. He had the light, but he told it by heart now, over and over, explaining it to children, to adults, to townsmen and hillers who had never seen the inside of modern buildings, who had to be told – so many things. Ma Elly and her folk sat nearest, Cloud with that habitual frown on his face, and Dal listening soberly; and Pia and young Tam solemn as the oldest. Twenty gathered here, crowded in; and there were others, too many to get into the shelter at once, who would come in on their turn. They came because he could read the books, more than Elly herself – he could tellwhat was in them in ways the least could understand. Cloud valued him. Pia came to his bed, and called him my Deanin a way proud and possessive at once.

In a way it was the happiest period of his life. They cared for him and respected him; they listened to what he had to say and took his advice. He gave them a tentative love, and they set him in a kind of special category – except Pia, who made him very special indeed; and Cloud and Dal who adopted him and ma Elly who talked about the past with him and Tam who wanted stories. At times the village seemed all, as if the other had never been.

But he could read more than he could say. He interpreted; it was all that he could do. He was alone in what he understood and he understood things that tended to make him bitter, written in the hands of long‑dead men who had seen the world as strangers. He could go to the wire again. They might take him back. But the bitterness stood in the way. The books were his, his revenge, his private understanding –

Only sometimes like tonight when calibans moved and shifted in the village, when he thought of the mounds which crept tighter and tighter about their lives –

– he was afraid.

VII

ELAI

i

178 CR, day 2

Cloud River Settlement

She was born into a world of towers, in the tallest of the Twelve Towers on the sandy Cloud, and the word went out by crier to the waiters below, huddled in their cloaks in a winter wind, that Ellai had an heir and the line went on.

Elai she was, in the new and simpler mode her mother had decreed–Elai, daughter of the heir to the Twelve Towers and granddaughter of the Eldest herself; and her mother, when her grandmother laid her red and squalling in her arms, clutched her with a tenderness rare in Ellai Ellai’s‑daughter–a kind of triumph after the first, stillborn, son.

Calibans investigated the new arrival in her cradle, the gray builders and the dignified browns, coming and going where they liked in the towers they had built. An ariel laid a stone in the cradle, for sun‑warmth, as she did for her own eggs, of which she had a clutch nearby. A gray, realizing someone’s egg had hatched, brought a fish, but a brown thoughtfully ate it and drove the gray away. Elai enjoyed the attention, the gentle nudgings of scaly jaws that could have swallowed her whole, which touched ever so carefully. She watched the flutter of ariel collars and the blink of huge amber eyes as something designed to amuse her.

When she walked, tottering between Ellai’s hands and an earthen ledge of her mother’s rooms, an ariel watched–and soon learned to scamper out of the way of baby feet. They played ariel games, put and take the stone, that sometimes brought squalls from Elai, until she learned to laugh at skillful theft, until her stones stayed one upon the other like the ariels’.

And the day her grandmother died, when she was hustled into the great topmost hall to put her small hand in Ellai Eldest’s and bid her goodbye–Scar got up and followed her out of the room, the great brown which was her grandmother’s caliban–and never would return. It was a callous desertion: but Calibans were different, that was all, and maybe Ellai Eldest understood, or failed to know, sinking deeper into her final sleep, that her life’s companion had gone away and traded allegiances.

But there was consternation in the Tower. Ellai’s presumed heir, Ellai‑almost‑eldest, stood watching it. There was silence among the servants, deathly silence.

Ellai Eldest passed. The caliban Scar should have pined over its dead, or suicided after the manner of its kind, refusing food, or swimming out to sea. Instead it luxuriated, hugely curled about young Elai on the floor, bearing the stumbling awkwardness of young knees in its ribs and the slaps and roughness of infant play. It simply closed its eyes, head lifted, collar lowered, as if it basked in sunlight instead of infant pleasure. It was happy this evening. The child was.

Ellai‑Now‑Eldest reached beside her own chair and met the pebbly hide of her own great brown, Twig, which sat quite, quite alert, raising and lowering her collar. If Scar had felt no urge to die, then Scar should have come to her, driven Twig away and appropriated herself, the new eldest, First in First Tower. Her own Twig could not dominate this one. She knew. At that moment Ellai foresaw rivalry–that she would never wholly rule, because of this, so long as that unnatural bond continued. She feared Scar, that was the truth. Twig did. So did the rest. Digger, Scar had been named, until his forays with Ellai‑now‑deceased against the intruders from the Styx, coming as they would the roundabout way, through the hills; then he had taken that raking cut that marked his ribs and renamed him. Scar was violence, was death, was power and already old in human years. And he might at this moment drive Twig away as an inconsequence.

He chose the child, as if Ellai in her reign over the Twelve Towers was to be inconsiderable, and the servants and the rulers of the other eleven Towers could see it when they came in the morning.

There was nothing that Ellai could do. She considered it from every side, and there was no way to undo it. Even murder crossed her mind, and infanticide: but this was her posterity, her own line, and she could not depend on another living heir, or tolerate the whispers, or dare the calibans. It had to be accepted as it was, and the child treated with tenderness. She was dangerous otherwise.

Children.

A child of eight sat in power on the distant Styx, Jin 12, with the old man dead. And Scar took to Elai. The Styx would stay quiet for at least a decade or so. And then–

A chill afflicted her. Her hand still stroked the plated scales of Twig’s beautiful skull.

Scar had simply bypassed her, this caliban whose occupation was conflict, as if all her reign was inconsequence, as if she were only preface. It portended peace, then, while children grew. A decade or so of peace. She would have that, and if she were wise, she would use it well, knowing what would come after her.

ii

184 CR, day 05

General Report, Gehenna Base to Alliance Headquarters

…The situation has remained stable over the past half decade. The detente between the Styx settlement and the Cloud River settlements continues in effect. Contacts with both settlements continue in an unprecedented calm. A Stygian tower has risen on the perimeter of the Base. In accordance with established policy the Base has made no move to prohibit construction or movement.

…The two settlements are undergoing rapid expansion in which some see an indication that humanity on Gehenna has passed a crisis point. The historical pattern of conflict has proceeded through the forested area outside Base observation, minor if constant encounters between Stygians and Cloud River settlers involving some loss of life, but never threatening the existence of either, excepting the severe and widespread hostilities of CR 124‑125, when flood and crop failure occasioned raids and widespread destruction. The current tranquil period, with its growth in population and food supply, is without precedent. In view of this historical pattern, and with careful consideration of long‑range objectives, the Base respectfully requests permission to take advantage of this opportunity to establish subtle and non‑interfering ties with both sides in the hope that this peaceful period may be lengthened. This modified and limited intervention seems justified in the hope of establishing Gehenna as a peaceful presence in the zone.

iii

185 CR, day 200

Message, Alliance HQ to Gehenna Base

…extend all cooperation to the Bureau agents arriving with this message, conducting extensive briefings and seminars on the Gehenna settlements…

…While the Bureau concurs that conditions warrant direct observation and increased contact, the Bureau cautions the Mission that prohibitions against technological imports and trade continue. In all due consideration of humanitarian concerns, the Bureau reminds the Mission that the most benign of interventions may result in premature technological advances which may harm or misdirect the developing culture…

iv

185 CR, day 201

Gehenna Base, Staff Meeting

“…meaning they’re more interested in the calibans than in human life,” Security said glumly.

“In the totality,” the Director said. “In the whole.”

“They want it preserved for study.”

“We could haul the Gehennans in by force,” the Director said, “and hunt them wherever they exist, and feed them tape until they’re model citizens. But what would theychoose, umn? And how many calibans would we have to kill and what would we do to life here? Imagine it–a world where every free human’s in hiding and we’ve dismantled the whole economic system–”

“We could do better for them than watch them.”

“Could we? It’s an old debate. The point is, we don’t know what we’d be doing. We take it slow. You newcomers, you’ll learn why. They’re different. You’ll learn that too.”

There were guarded looks down the table, sensitive outworlder faces.

“ Different, on Gehenna,” the Director said, “isn’t a case of prejudice. It’s a fact of life.”

“We’ve studied the culture,” the incoming mission chief said. “We understand the strictures. We’re here to review them.”

“ Different,”the Director said again. “In ways you won’t understand by reading papers or getting tape.”

“The Bureau appreciates the facts behind the designation. Union…is interested. Surveillance is being tightened for that reason. The quarantine makes them nervous. They wonder. Doubtless they wonder. Perhaps they’ve begun to have apprehensions of something beyond their intentions here. There will be negotiations. We’ll be making recommendations in that regard too. This differencewill have its bearing on policy.”

“Union back on Gehenna–”

“That won’t be within our recommendations. Release of data is another matter. A botched alien contact, happening in some other Union recklessness, might not limit its effects so conveniently to a single world. Release of the data is a possibility…educating Union to what they did here.”

There were frowns. The Director’s was deepest. “Our concern is human life here. Now. Our reason for the request–”

“We understand your reasons.”

“We have to do something with this generation or this settlement may take abrupt new directions.”

“Fears for your own security?”

“No. For what this is becoming.”

“The difference you noted.”

“There’s no time,” the Director said, “that I can see any assimilation of Gehenna into Alliance…without the inclusion of humans who think at an angle. You can tape them. You can try to change them. If you don’t understand what they are now, how do you understand them when they’ve come another hundred years, another two hundred on the same course? If you don’t redirect them–what do you do with them? Perpetual quarantine–into the millennia? Governments change. Policies change. Someday somebody will take them in…and whatthey take in…is being shaped in these first centuries. We have a breathing space. A little peace. The chance of contact.”

“We understand that. That’s what we’re here to determine.”

“A handful of years,” the Director said, “may be all we have.”

v

188 CR, day 178

Cloud River Settlement

There was land across the saltwater and Elai dreamed of it–a pair of peaks lying hazily across the sea.

“What’s there?” she had asked Ellai‑Eldest. Ellai had shrugged and finally said mountains. Mountains in the sea.

“Who lives there?” Elai had asked. And, No one, Ellai had said. No one, unless the starships come there. Who else could cross the water?

So Elai set her dreams there. If there was trouble where she was, the mountains across the sea were free of it; if there was dullness in the winter days, there was mystery in the mist‑wreathed isle across the waves. If there was No, Elai, and Wait, Elai, and Be still, Elai–on this side of the waves, there was adventure to be had on that side. The mountains were for taking and the unseen rivers were for swimming, and if there were starships holding them, then she would hide in burrows till they took their leave and she and a horde of brave adventurers would go out and build their towers so the strangers could not argue with their possession. Elai’s land, it would be. And she would send to her mother and her cousin Paeia, offering them the chance to come if they would mind herrules. The Styxsiders could never reach them there. The rivers there would never flood and the crops would never fail, and behind those mountains would be other mountains to be taken, one after the other.

Forever and forever.

She made rafts of chips of wood and sailed them on the surge. They drifted back and she leaned close and blew them out again. She made canopies for passengers on her most elaborate constructions, and did straw‑dolls to ride, and put on pebbles for supplies and put them out to sea. But the surge toppled the stones and swept off the dolls and the raft came back again, so she made sides so the passengers should stay, carved her rafts with a precious bone knife old Dal had made her, and set them out with greater success.

If she had had a great axe such as the woodcutters used, then she might build a real one: so she reckoned. But she tried her bone knife on a sizeable log and made little progress at it, until a rain swept it all away.

So she sat on the shore with Scar, bereft of her work, and thought how unfair it was, that the starships came and went so powerfully into the air. She had tried that too, made ships of wood and leafy wings that fell like stones, lacking the thunderous power of the machines. One dreamed. At least her sea‑dreams floated.

The machines, she had thought, made wind to drive them. If only the wind which battered at the shore could get all into one place and drive the ships into the sky. If only.

She saw leaves sail, ever so much lighter on the river’s face, whirling round and about. If she could make the ships lighter. If she could make them like the leaves… If they could be like the fliers that spread wings and flew… She made wings for her sea‑borne ships, pairs of leaves, and stuck them up on twigs, and to her delight the ships did fly, if crazily, lurching over the water and the chop until they crashed on rocks.

If she had a woodcutter’s skill, if she could build something bigger still–a great sea‑ship with wings–

She sailed carved ships at least to the rocks an easy wade offshore, and imagined those rocks as mountains.

But always the real, the true mountains were across the wider sea, promising and full of dreams.

She watched the last of her ships wreck itself and it all welled up in her, the desire, the wishing, that she could be something more than ten years old and superfluous to all the world. She could order this and that about her life–she had what she wanted in everything that never mattered. She could have gone hungry: she was willing to go hungry in her adventures, which seemed a part of war: she had heard the elders talking. She was willing to sleep cold and get wounds (Cloud Oldest had dreadful scars) and even die, with suitable satisfaction for it–the fireside tales were full of that, a great deal better than her grandmother who had slept out her end (but it was her youngly dead uncle they told the best stories of)–in all she could have done any of these things, imagining herself the subject of tales. But she had no axe and her knife was fragile bone.

She did have Scar, that she relied on for consolation, for near friendship, for pride. He had fought the Styx‑folk. When she climbed up to his back she was something more than ten. He played games with her. He was adult and powerful and very, very dangerous, so that Ellai herself had taken her aside and lectured her severely about responsibility. She could feel the power of him, that she could lie on and be rough with and laugh at boys who were still playing at stones with ariels, who teased her with their adolescent manhood and retreated in real fear when Scar shouldered his way into any imagined threat they posed. Then they remembered what he was–and Scar was ever so coy about it, giving way to lesser browns belonging with the elders: biding his time, that was what, only biding his time until his rider grew up to him.

Scar knew her. Only the rest of the world misapprehended what she was. She waited for this revealing with a vast discontent, and the least gnawing doubt, looking at the great brown lump sunning himself with a caliban smirk, among the rocks above the beach.

She whistled, disconsolate with her shipwreck. One lamplike eye opened, the tongue flickering. Scar heaved himself up on his legs in one sinuous rise and looked at her, lifting his collar. He was replete with fish. Satisfied. But because she wanted he came down, lazy with the sun, presenting his bony side jaws for a scratching, the soft underjaw for a stroking.

She touched him, so, and he sank down on his full belly and heaved a sigh. She reached up behind the collar for that bony ridge which helped her mount, planted a bare sandy foot on his foreleg and swung up astride. Her boots and breeches were up there on the rocks: they had had their swim in the saltwater and the seat of her scant undergarments was still wet from a recent wade among the rocks for vantage. Scar’s pebbly hide was hardly comfortable to bare legs and partly bare bottom, but she tapped her foot and headed him for the sandy part of the shore, to cool them both in the sea, to salve her melancholy in games.

They went onto the shelf of sand, a great smooth ripple spreading out around them, a twisting motion to which she swayed as Scar used his tail and hit that buoyant stride that was the freest thing in the world, she reckoned, short of flying. Scar did not take this water into his nose: it was too bitter for him and too salt. He kept his head aloft and paddled now, soaking her.

And then this madness came on her as she looked at the mountains beyond the sea, clearer than ever on this warm day.

She whistled softly, nudged him with her toes and heels, patted him with her hands. He turned, first his head and then the rest of him down to his tail, so that she felt the shift of him, every rippling of muscle, taking this new direction. The waves splashed up and broke about Scar’s face, so that he lifted his head still higher and fought the harder, great driving thrusts of his body. Salt was in her mouth and it was hard to see with the sting of it in her eyes, hard to keep her grip with the lurching whip of Scar’s body through the waves, the constant working of his shoulders. In a salt‑hazed blink she realized they were beyond the rocks, well beyond, and of a sudden they were being carried aside from their course. She used her heel, she urged at Scar: he twisted his whole body trying to fight it, and still they were losing against the rush of water.

In some remote area of her mind she was afraid: she was too busy hanging on, too busy trying to discover a way out of it to panic. She kicked at Scar when he turned into the rush and then they were going much faster.

Something breached near them. A steamy plume blew on the wind, and vanished, and then the fear got through. She tried to see where that breaching dark shape had gone, and quite as suddenly something brushed them, a back bigger than any three browns broke the water right next to them and Scar was jolted under her, twisting suddenly, flailing in a roll that left her clinging only to the collar.

He ducked under, a brief twist of the body, and then he moved with all the fluid strength he could use. She clung to his bony plates and skin till her fingers ached, holding her breath, and then she lost him. She launched out on her own in sure, desperate strokes, looking for the surface, blind, and knowing there was something else nearby, something that might take half her body in a gulp, and the moving water resisted her strokes, wanting to pull her down.

She surrendered one direction, gathered speed and broke through to light in a spray of droplets, sucked air and water into her throat and coughed and flailed to stay afloat.

She felt the contact coming under the surface, a shock of water, a numbing blow against her legs. She swam in utter panic, striking out for the shore, the distant pale sand that wavered in her streaming eyes. Other water‑shocks flashed about her–a body brushed hers, a claw raked her and threw her under. She kept swimming, weaker now, failing and choking, driving herself long after she stopped seeing where she was going and after she knew the weak motions of her arms and legs could never make it.