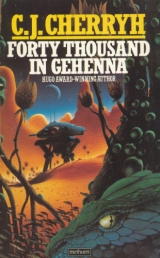

Текст книги "Forty Thousand in Gehenna"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

They put no restraint on him. They needed none but the darkness and the earth, the hardpacked earthen walls that he could feel and not see in the absolute and lasting night. His fingers were torn and maybe bleeding: he had tried to dig his way to safety, even to dig himself a niche in which to put his back, so that he could defend himself when they came at him, but he had no sense which way the outside was, or how deep they had taken him–he might be trying to dig through the hills themselves. He found a rock once, and battered one of his attackers with it, but they used their needles and had their revenge for that, a long, long time–like the times he had tried to crawl away, feeling his blind way through the dark, until he had ended with the hissing blast of a Caliban’s breath in his face, the quick scrabble of claws, the thrusting of a great blunt nose that knocked him off his feet–lying there with a great clawed foot bearing down on his ribs and throat until human hands arrived with needles; or running into such hands direct–No, there was no fighting them. He did not know why he did not die. He thought about it, young as he was, and thinking he could smother himself in the earth, that he could dig himself a grave with his lacerated fingers and hide his face in it and stop his breathing with dirt. He dug, but they always came when they heard him digging–he was sure that they heard. So he kept still.

They brought him raw fish to eat, and water to drink which might or might not be clean. At such times they touched him, constant touches like the nagging of children, and then more than other times he thought of dying, mostly because feeding was the one thing they did to keep life in him. He was always cold. Mud caked on his clothes and his skin, dry and wet by turns, wherever in the earthen maze they had moved him last. His hair was matted with filth. His clothes were torn, laces snapped with his struggles, and he tried to knot them back together because he was cold, because clothes were all the protection he had.

He lay still finally, weaker than he had begun, with druggings and struggles and food that sometimes his stomach heaved up or that his body rejected in cramping spasms; and even his condition did not repulse the females among them, who tormented him with some result at the beginning, when it took all of them, sealing up the exits and herding and hunting him through the narrow dark, and hauling him down with weight of numbers–but they got nothing from him now, nothing but a weary misery, terror that they might kill him in their frustration. That was what he had sunk to. But they were always silent, gave him no hint of humor or anger or whether they were themselves quite mad. He was himself passing over some manner of brink; he even knew this, in a far recess of his mind where his self survived. If he were set out again on the riverside–he thought of Styx as the outside, having lost all touch with the sunny hills–if he were set outside to see the daylight again, the sun on the water, the reeds in the wind–if he were free–he did not think he would laugh again. Or take sunlight for granted. He would never be a man again in the narrow sense of man–because sex had not gone dead in him, but become personless, unimportant; or in the wider sense, because he had been gutted, spread wide, to take into his empty insides all the darks and slitherings underearth, all the madness and the windings underground. He had nothing in common with humanity. He felt this happening, or realized it had happened; and finally knew that this was why he had not died, that he had reached a point past which he had more interest in this darkness, the sounds, the slitherings, than he had in life. It had all begun to give him information. His mind received a thousand clues in the midst of its terror, grew tired of terror and concentrated on the clues.

They came for him. He thought it might be food when he heard them, but food smelled, and he caught no such smell, so he knew that it was himself they wanted, and he lay quite still, his heart speeding a little, but his mind reasoning that it was only inconvenience, a little pain to get through like all the other pains, and after that he would still be alive, and still thinking, which was something still more promising than dying was.

But they gathered about him, a great lot of them by the sounds, and jabbed him with one of their needles. He screamed, outraged by that trick, of a sudden wild as a caliban could go. He struck at them, but they skipped silently out of reach. Something slithered across his chill‑numbed legs, and that was an ariel, who ran where they liked in the mounds. He struck at it with a shudder, but it eluded him. Then he sat still, waiting while the numbness crept over him, while his mouth seemed full of fluff and his extremities went dead.

They gathered him up then, feeling over his body to be sure which way he was lying, dragged at his wrists to take him through the narrow tunnel, while he was as paralyzed as he had been when they brought him into this place. His mind still worked. He wished that they would turn him over on his belly because dirt fell into his eyes.

Then there began to be daylight, and they were going up, up, and out of the tunnel into the glaring sun. Light crossed his eyes like a knife, brought tears, and vanished again in a whirl of leaves living and dead as one of them slung him up and over his shoulder.

They passed him then to another, who did not support him, but held him about the chest and dragged him into the river. The shock of water got to him. He tried again to move, to throw his head, to at least get air; but a hand cupped his chin and the water took all but his face and sometimes washed over him. He choked, incapable of moving as his limbs dragged through the water. Terror grew too much then. The senses dimmed, from want of air, from the hammering of his heart–and then they were hauling him out on the other side, and took up his sodden, leather‑clad body sideways while his head fell lowest and a spasm of his throat and stomach sent up a thin stream of choking fluid. His limbs took on a little life, a slight degree of response, but now they dragged him up again, pulling him up a brushy mound on the opposite side of the river, and the dark took them all back again.

He convulsed once, a spasm which emptied out his stomach, lay still and shallow‑breathing when it had passed, and the hands which had let him go when he doubled up took him again by the wrists and collar and by the knees, carrying him in rapid jolting through the dark. He heard a sound, a faint protest from his own throat, and stopped it, silent as this whole world was silent. He had lain for unguessable time in the dark learning the rules and now they stripped all the rules away. He was truly gone now. The paralysis of his body had receded to a kind of numbness, but he failed to do anything to help himself, blind, completely blind, and fainting for long black periods hardly distinguishable from his waking in the dark, except that the fainting was without pain, and that such periods were gratefully frequent.

They stopped finally. He thought perhaps that they had gotten to some place which satisfied them, and that they might go away and let him lie, which was all he wanted, but they stayed: he heard their panting breaths close by, and the small movements they made. He heard the skittering of ariels and the slither of one of the calibans in the vast silence. Perhaps, he thought, they meant him some harm when they had rested. Maybe they were renegades or crazier than the rest, with a notion to have privacy for their sport. He meant to fight them if it got to that, make them stick him again, because that brought some numbness.

One moved, and the others did, fingering him with their blind touches; he struck once, but they got his arms and legs and simply picked him up again, having had their rest. He knew what they could do, and had no desire for the needle under those terms, and even made feeble attempts to cooperate when they had come to a low place, so that finally it seemed to get through to them that he would go with them on his own. More and more they let him carry himself for brief periods, taking him up when he would stumble, when his exhaustion was too extreme.

And then there was a confusion in the dark, a meeting, he thought, and a different smell about those they met. He was pushed forward, let go, taken again, and after that snatched up again, so that he knew he was in different hands. Tears leaked from his eyes. The others had understood something, he had gotten somethingthrough to the others to better his condition, and they changed the game again–snatched him off and hauled him along with more roughness than before. He went limp and let them do what they liked, afraid of needles, afraid of utter helplessness. Such strength as he had left in him, he saved, that being the only canniness he had left.

They climbed. He gathered his mind from the far corners of its retreat and tried to think again, getting information again–ascent, spirals, dry earth.

And light. He tried to lift his head from its backward tilt, could not hold it, watched the light grow in his upside down vision, making a hazy silhouette of the man who had his arms.

An earthen chamber with light coming from a window. A man sitting on the floor, another shadow in his hazed vision.

They let him down. He lay there a moment, frozen in the silence of them, turned his head to the seated man–one of their own, but old, the oldest man he had ever seen, bald and withered and clothed in a oneshouldered robe that held at least the memory of red. The others squatted in their rags. The old man sat and waited.

It was a time before he gathered his wits at all. He levered himself up on his arm, squinted up at the light as the silhouette of a Weird set a large bowl of water in front of him. He bent and cupped up water to drink and wash the sickness from his mouth, drank again and again and splashed clean water over his face while his hands shook and spilled a lot of it in his lap. He blinked at the old man, having gotten used to insanity and expecting more of it.

“Speak,” the old man said softly.

A rock might have spoken. The old man sat. A smallish ariel rested in his lap. His fingers played with it, stroking its ruffled fringes.

Jin needed a time to consider. He wiped his face yet again, drew his knee up and rested his arm on it because he was not steady even sitting. He looked at the old man very long. “Why am I here?” he asked finally, as still, as hushed. But the old man did not answer, as crazed as the rest of them. Or that was not the speech the old man wanted. The silence between them went on, and Jin hugged his knee against him to keep himself from shaking. There was warmth here. It streamed through the window, circulated with the air. Summer went on outside as if it had never stopped. “They found me by the river,” Jin said then, precisely, carefully, in a voice hardly more than a whisper. He recalled the shooting of the caliban and blocked that from his mind, focussing narrowly on the old man in front of him, whose skull was naked of hair, whose thin beard was white and clean. Clean. He never thought to see cleanliness again. He reeked of mud and sweat and excrement; his clothes were caked with filth. “It must have been days ago–” He went on talking, reckoning for the first time that someone was listening to him. “They brought me across the river. I don’t know why.”

“Name.”

“Jin.”

The aged head lifted. Watery dark eyes focussed on his for a long and quiet time. “My name is Green.”

The name hit his mind and settled, a cold, cold feeling. Family stories. They knew each other. He saw that. “Let me go,” he said. “Let me out of here.”

“Someday,” Green whispered, a rusty sound like something long unused. A long silence. “A brown is dead.”

“An accident. No one meant it.”

Green simply stared, then took pebbles from his lap and placed them in a line on the earthen floor. The ariel watched, then scrambled over his knee and onto the hardpacked earth, a flailing of limbs. It stood up on its legs, flicked its collar, studying the matter with one cocked eye. Then it began to move the pebbles, laying them in a heap.

“Let me leave,” Jin said hoarsely, focussing with difficulty. “It was an accident.”

“Do you understand this Pattern?” Green asked. “No.” He answered himself, and gathered up the stones, laid them down again, only to have the ariel move them into a heap. It went on and on.

“What do you want with me?” Jin asked at last. A tremor had started in his arms, exhaustion, and a pain in his gut. “Can’t we get it done?”

“Look at this place,” Green said.

He lifted his eyes and looked around him, the earthen walls, the window, the rammed‑earth floor scored with claws far larger than the ariel’s. The Weirds crouched in shadow beneath the window.

Green clapped his hands, twice, echoing in the stillness. And far away, down somewhere in the shadows something stirred. There was a sough of breath, and that something was large.

Jin froze, his arms locked about his knees. He looked at the window, at sunlight, at a way of escape or dying.

“No hurt,” Green said softly.

It came up from below, a whuff of breath, a dry scraping of claws, the thrusting of a blunt, bony‑collared head up out of the entry to the room, a head as large as the entry itself. Jin scrambled back until he felt the wall behind him, and more of it kept coming, a brown, but a bigger brown than ever he had seen. Its eyes were green‑gold. Its crest was touched with green. It settled on its belly, curling its tail around the curving of the wall beyond Green, reaching from side to side of the room, and the Weirds never stirring from where they sat. The brown craned its neck, turned a fistsized eye in Jin’s direction, came up on its legs and moved closer.

Jin shut his eyes, felt warm breath and the flickering of its tongue about his face and throat. The tongue withdrew. The head turned again to stare at him with an eye large as a human head. The tongue licked out, thick as his arm.

“Be calm,” Green whispered. Jin huddled against the wall, beside huge clawed feet. The head swung over him, overshadowing him; and quietly it bent and nudged him with its jaws.

He cried out; it whipped away, dived down into the dark of the access with a last slithering of its tail. Jin stayed where he was against the wall, shivering.

“Others died,” Green whispered, sitting again where he had sat, calmly placing his stones one after the other. No, the stones said, chilling with hope. Green gathered up the stones again, strewed them one after the other, went on doing this time after time while the ariel crouched near and watched, while the rougher, ragged Weirds crouched watching in their silence.

Jin wiped his mouth and grew quieter, the shivers periodic. He was not dead. He had not died. There was an anger stored away inside him, anger at what he was, that he could not stop shivering, because they could do whatever they liked. He remembered what he had suffered, and how he had screamed, and how all his wit and hunter’s skill had let him down. He no longer liked being what he had been–vulnerable; he would never be again what he had been–naive. All his life people must have seen these things in him. Or all his kind were like him. He loathed himself with a deep and dawning rage.

xv

Year 89, day 222 CR

Main Base

Dean came into the lab, stood, hands behind him, coughed finally when Spencer stayed at work. Spencer turned around.

“Morning,” Spencer said.

“Morning, sir.” He kept his pose, less than easy, and Spencer frowned at him.

“Something wrong, Dean?”

“I heard–”

“Is this panic all over the town, then?”

“The soldiers moved last night. To the wire.”

“An alarm. An empty one.”

“Hillers haven’t shown up in days.”

“So I understand.” Spencer came closer, rested his portly body against the counter and leaned back, arms folded. “You here to say something in particular, Dean?”

“Just that.”

“Well, I appreciate your report. I reckon the hillers are a little nervous, that’s all.”

“I don’t know what I can learn out there in town if there aren’t any hillers coming in.”

“I think you serve a purpose.”

“I’d really like to be assigned inside.”

“You’re not nervous, are you?”

“I just really think I’m not serving any purpose out there.”

“It’s rather superstitious, isn’t it? I detect that, in the town.”

“They’re quite large, sir. The calibans.”

“I think you serve as a stabilizing influence in the town. You can tell them that the station’s still up there watching and we don’t anticipate any movement. It’s probably due to some biocycle. Fish, maybe. Availability of food. Population pressures. You’re an educated man, Dean, and I want you right where you are. We’ve got a dozen applications for Base residency in our hands, a rush on applications for one open job. That disturbs me more than the calibans. We’ve got a whole flood of field workers on the sick roster. I’m talking twenty percent of the workers. Not a fever in the lot. No. We’re not pulling you inside. You stay out until the crisis is over.”

“That could be a while, Dr. Spencer.”

“You do your job. You keep it down out there. You want your privileges, you do your job, you hear me? No favors. You talk to key people and you keep the town quiet.”

“Yes,” Dean said. “Sir.” He jammed his hands into his pockets and nodded a good morning, trying to manage his breathing while he turned and walked out.

His mother was dead. Last month. The meds had not saved her this time: the heart had just gone. The town house was empty except when he moved in. His neighbors hardly spoke, coveting the house so conveniently sharing a wall with their overcrowded one. He had no friends: older than the adolescent scholars, he was anomaly in his generation. He had no wife or lover, being native and untouchable on the main base side of the line, outsider and unwanted in the town.

He walked the quadrangle of Base, among the tall outworlder buildings, among strange concrete gardens which disturbed him to look at, because they made no sense in their forms of twisted concrete, and he saw obscure comparisons to Patterns, which hillers made to confuse townsmen. Just beyond the enclosure made by the buildings and their concrete walls, he entered the gatehouse where he stripped and hung his Base clothes in a locker, and changed to townsman coveralls, drab and worn. They were a lie; or the other clothes were: he was not, this morning, sure.

He went out again, passed the guard who knew him, the outworlder guard who looked at him and never smiled, never trusted him, always checked at the tags and the number on his hand as if they had changed since yesterday.

The guard made his note in the record, that he had left the Base. Dean went out, from concrete garden to a concrete track that led into the town, making a T north and south, one long true street which was all the luxury the town had. The rest were dirt. The buildings were native stone and brick; and the clinic, which was featureless concrete–that was the other gift from the Base. Dirt streets and ordinary houses raised by people who had forgotten architects and engineers. They had a public tap on every street; a public sewer to take the slops, and a law to make sure people took the trouble. There was a public bath, but that stank of its drains, and kept the ground around it muddy, to track in and out. There were fields as far as the hills, golden at this time of year; and the sentry towers; and the wire, wire about the fields, about the town, and concrete ramparts and guardstations about the Base. The wire made them safe. So the outworlders said.

xvi

Year 89, day 223 CR

The Hiller Village

A caliban came at twilight, carrying a rider, a thing no one had ever seen; it came gliding out of the brush near old Tom’s house and another one came after it. A small girl saw it first and stood stock still. Others did the same, excepting one young man who dived into the common hall and brought the whole village pouring out onto the rocky commons.

It was a man on the Caliban’s shoulders, all shadowy in the twilight, the caliban itself indistinct against the brush, and a second caliban, smaller, came after with a man sitting on that one too. The calibans stopped. Weirds materialized out of the brush around the camp, shadows in the fading colors of night’s edge, some naked and some wearing dull‑hued bits of clothes.

The man sitting on the Caliban’s neck–the first one–lifted his arm. “You’ll leave this place,” the voice came ringing out at them, speech from a Weird…and that alone was shock enough, but the caliban moved forward, light and slow as the clawed feet could set themselves on the stone, and the hillers gathered on the doorstep of the common‑hall gave backward like the intaking of a breath. There were hunters among them, but no one had brought weapons to evening meal; there were elders, but no one seemed to know what to say to this; there were children, and one of the youngest started to cry, setting off an infant, but parents hugged their faces against their shoulders and frantically hushed them.

Other calibans were around the camp, some with riders, moving ghostlike through the brush. And smaller calibans, like the witless grays. And smaller still, a handful of the village ariels came slithering out into the empty space between calibans and hall and froze there, heads up, fringes lifted, a thing peculiarly horrid, that creatures the children kept for pets should range themselves with such an invasion.

“The village is done,” the intruder said. “Time to move. Calibans are coming–tonight. More and more of them. The times change. These strangersinside the wires, these strangers that mark you to go through their gates, that take food enough from the town to get fat, they’ve got everything. And they shoot browns. That doesn’t do, no, that doesn’t do at all. There’s no more time. There’s new Patterns, across the river, there’s things no outsider ever saw, there’s a safe place I’ll bring you to, but this place…this village is going to be for the wind and the ariels tomorrow, like the domes they tell about, like those, dead and dark. The stone underfoot won’t protect you. Not now.”

“That’s Jin,”someone said under his breath, a tone of horror, and the name went whispering through the village. “That’s Jin, that was lost on riverside.”

“Jin,” a man’s voice said, and that was Jin Older, who pushed his way out in front of everyone, with tears and shock in his voice. “Jin, come down from that, come here. This is your people, Jin.”

Something hissed. Jin Older slapped at something in his neck about the time his wife pushed through the crowd to get to him; and other kin–but Jin Older fell down, and a few tried to see to him, but one broke to ran for cover–a second hissing, and that woman staggered and sprawled.

“Take what you want,” Jin shouted, pointing a rigid arm at the village about them. “What you’ll need, you gather up–But plan to leave. You thought you were safe here, built on rock. But you leave these buildings, you just leave them for the flitters and be glad. You move now. They won’t like waiting.”

And then: “ Move!” he shouted at them, because no one did, and then everyone did, a panicked scattering.

Cloud reached his own house, out of breath, and fumbled in the dark familiar corner for his bow, with only the fireplace coals to see by. He found his quiver on the peg, slung that to his shoulder and turned about again facing the door as a flurry of running steps came up to it, a flood of figures he knew even in the dark.

“It’s me,” he said before they could take fright–his wife Dal, his sister Pia, his grandmother Elly and his own son Tam, eight years old. His wife hugged him; he hugged her one‑armed, and hugged his son and sister too. Tam was crying as he made to go; ma Elly put herself in his way.

“No,” Elly said. “Cloud, where are you going?”

He was afraid at the thought of shooting humans and calibans, but that was what he was off to, what was about to happen out there–what had already started, on the invaders’ side. He heard shouting, heard the hiss of calibans. Then he heard faint screams.

“Come back here.” Ma Elly clenched his shirt, pulled at him with all her might, a stout woman, the woman who had mothered him half his life. “You’ve got a family to see to, hear?”

“Ma Elly–if we don’t stop them out there together–”

“You’re not going out there. Come back here. They’ll kill you out there, and what good is that?”

His wife held him, her arms added to ma Elly’s, and young Tam held to his waist. They pulled him inside, and he lost his courage, lost all the fire that urged him to go out and die for them, because he was thinking now. Then what? ma Elly asked, and he had no answer, none. He patted his wife’s shoulder, hugged his sister. “All right,” he said.

“Gather everything,” ma Elly said, and they started at it, in the dark. Young Tam tossed a log on the hearth–“ No,”Cloud said, and pulled the boy back and raked the log out with a stick before it took light, a scattering of coals. He took the boy by the shoulders and shook him. “No light. Get all the clothes you can find. Hear?”

The boy nodded, swallowed tears and went. Cloud looked rightward, where ma Elly was down on her knees among the scattered coals wrestling with the flagstones.

He squatted down and levered it up for her with his knife, asked no question as she pulled up the leather‑wrapped books that were the treasure of Elly’s line. She hugged them to her and he helped her up while the business of packing went on around them. “Not going to live in any caliban hole,” ma Elly muttered. He heard her voice break. He had not heard Elly Flanahan cry since his mother died. “You hear me, Cloud. We go out that door, we keep going.”

“Yes,” he said. If he had seen no other way he would have surrendered for his family’s sake, for nothing else; but what ma Elly wanted suddenly fell into place with all his instincts. Of course that was where they would try to go. Of course that was where they had to try. Only–his mind shuddered under the truth it had kept shoving back for the last few moments–the invaders would get the old, the weak, the children: the calibans would have them, and the darts would strike down those that stood to fight. All that might get away was a family like his, with all its members able to run, even old ma Elly. Coward, something said to him; but–Fool, that something said when he thought of fighting calibans and darts at night.

He took up a bundle of something his wife gave him, and very quietly went to the door and looked out into the commons, where calibans moved between them and the common‑hall lights. It was quiet yet. “Come on,” he said, “keep close. Pia, go last.”

“Yes,” she said, a hunter herself, for all she was fifteen. “Go on. I’m behind you.”

He slipped out, strung his bow, nocked an arrow as he went around the side of the house, toward the slope of the hill.

A gray thrashed toward him, sentry in the bushes. He whipped the bow up and fired, one true venomed shot. The gray hissed and whipped in its pain, and he ran, down the slope, collected his family again at the bottom, out of breath as they were, and started off again, a jog for a time, a walk, and then a mild run, gaining what ground they could, because he heard panic behind him.

“Fire,” Pia breathed.

He looked back. There was. He saw the glow. Houses were afire.

“Keep walking,” ma Elly said, a gasp for air. “Keep walking.”

A noise broke at their backs, a running, but not of caliban feet. Cloud aimed an arrow, but it was more of their own coming.

“Who are you?” Cloud hissed at them. But the runners just kept running–of shame, perhaps, or fear. His own family went as fast as it could already, and soon he carried young Tam, and Dal took the books from ma Elly, who tottered along at the limit of her strength.

He wept. He did not know it until he felt the wind on his face turn the tears cold. He looked back from time to time at the glow which marked the end of what he knew.

And if the calibans would hunt them further, if they had a mind to, he knew nowhere that they were safe. He only hoped they would forget. Calibans did, or seemed to, sometimes.

xvii

The Town

The snap of wires, flares in the dark–there was screaming, above all the commotion of people running in the streets.

They surged at the gates, at the wire, but the Base never saw them.

“Open up,” Dean cried, screamed, lost among the others. “Open the gates–”

But the Base would not. Would never open the gates at all, to let a rabble pour into their neat concrete gardens, come too near their doors, bring their tradecloth rags and their stink and their terror. Dean knew that before the others believed it. He turned away, ran, panting, crying at once, stopped in a clear place and looked over his shoulder at nightmare–

–at a seam opening in the earth, at houses beginning to fold in upon themselves under the floodlights and collapse in heaps of stone–at the rip growing and tilting the slabs of the paved road, and under the crowd itself, people falling.

A renewed screaming rang out.

The rift kept travelling.

And suddenly in the dark and the floodlights a monstrous head thrust up out of the earth.

Dean ran, everything abandoned, the way the calibans themselves had opened, across the ruined fields.

Once, at screams, a thin and pitiful screaming from behind, he looked back; and many of the lights had gone out, but such as were left shone on a puff of smoke, a billowing cloud amid the tall concrete buildings of main Base…and there was a building less than there had been.

The calibans were under the foundations of the Base. The Base itself was falling.

He ran, in terror, ran and ran and ran. He was not the only one to pass the wires. But he stayed for no one, found no companion, no friend, nothing, only drove himself further and further until he could no longer hear the screams.