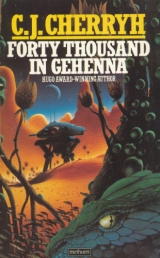

Текст книги "Forty Thousand in Gehenna"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

“Morning,” Conn wished him. Davies came out of his private reverie long enough to look up as he went by. “Morning,” Davies said absently, and went back to his computers and his books and his endless figuring.

That was the way of it now, that as fast as they built, the old pieces fell apart. Conn turned his mind back to the permafax sheets in his lap and made more adjustments in the plans which had once been so neatly drawn.

Two things went well. No, three: the crops flourished in the fields, making green as far as the eye could see. And Hill’s fish came up in the nets so that a good many of them might be sick of fish, but they all ate well. The plumbing and the power worked. They had lost some of the tape machines; but others worked, and the azi showed no appreciable strain.

But the winter–the first winter…

That had to be faced; and the azi were still under tents.

x

Day 346 CR

The wind blew and howled about the doors of the med dome. Jin sat in the anteroom and wrung his hands and fretted, a dejection which so possessed him it colored all the world.

She’s well, the doctors had told him; she’s going to do well. He believed this on one level, having great trust in Pia, that she was very competent and that her tapes had given her all the things she had to know. But she had been in pain when he had brought her here; and the hours of her pain wore on, so that he sat blank much of the time, and only looked up when one of the medics would come or go through that inner corridor where Pia was.

One came now. “Would you like to be with her?” the born‑man asked him, important and ominous in his white clothing. “You can come in if you like.”

Jin gathered himself to unsteady legs and followed the young born‑man through into the area which smelled strongly of disinfectants–a hall winding round the dome, past rooms on the left. The born‑man opened the first door for him and there lay Pia on a table, surrounded by meds all in masks. “Here,” said one of the azi who assisted here, and offered him a gown to wear, but no mask. He shrugged it on, distracted by his fear. “Can I see her?” he asked, and they nodded. He went at once to Pia and took her hand.

“Does it hurt?” he asked. He thought that it must be hurting unbearably, because Pia’s face was bathed in sweat. He wiped that with his hand and a born‑man gave him a towel to use.

“It’s not so bad,” she said between breaths. “It’s all right.”

He held onto her hand; and sometimes her nails bit into his flesh and cut him; and betweentimes he mopped her face…his Pia, whose belly was swollen with life that was finding its way into the world now whether they wanted or not.

“Here we go,” a med said. “Here we are.”

And Pia cried out and gave one great gasp, so that if he could have stopped it all now he would have. But it was done then, and she looked relieved. Her nails which had driven into his flesh eased back, and he held onto her a long time, only glancing aside as a born‑man nudged his arm.

“Will you hold him?” the med asked, offering him a bundled shape: Jin took it obediently, only then realizing fully that it was alive. He looked down into a small red face, felt the squirming of strong tiny limbs and knew–suddenly knew with real force that the life which had come out of Pia was independent, a gene‑set which had never been before. He was terrified. He had never seen a baby. It was so small, so small and he was holding it.

“You’ve got yourselves a son,” a med told Pia, leaning close and shaking her shoulder. “You understand? You’ve got yourselves a little boy.”

“Pia?” Jin bent down, holding the baby carefully, oh so carefully–“Hold his head gently,” the med told him. “Support his neck,” and put his hand just so, helped him give the baby into Pia’s arms. Pia grinned at him, sweat‑drenched as she was, a strange tired grin, and fingered the baby’s tiny hand.

“He’s perfect,” one of the meds said, close by. But Jin had never doubted that. He and Pia were.

“You have to name him,” said another. “He has to have a name, Pia.”

She frowned over that for a moment, staring at the baby with her eyes vague and far. They had said, the born‑men, that this would be the case, that they had to choose a name, because the baby would have no number. It was a mixing of gene‑sets, and this was the first one of his kind in the wide universe, this mix of 9998 and 687.

“Can I call him Jin too?” Pia asked.

“Whatever you like,” the med said.

“Jin,” Pia decided, with assurance. Jin himself looked down on the small mongrel copy Pia held and felt a stir of pride. Winter rain fell outside, pattering softly against the roof of the dome. Cold rain. But the room felt more than warm. The born‑men were taking all the medical things away, wheeling them out with a clatter of metal and plastics.

And they wanted to take the baby away too. Jin looked up at them desperately when they took it from Pia’s arms, wanting for one of a few times in his life to say no.

“We’ll bring him right back,” the med said ever so softly. “We’ll wash him and do a few tests and we’ll bring him right back in a few moments. Won’t you stay with Pia, Jin, and keep her comfortable?”

“Yes,” he said, feeling a tremor in his muscles, even so, thinking that if they wanted to take the baby back again later, after Pia had suffered so to have it, then he wanted very much to stop them. But yes was all he knew how to say. He held on to Pia, and a med hovered about all the same, not having gone with the rest. “It’s all right,” Jin told Pia, because she was distressed and he could see it. “It’s all right. They said they’d bring it back. They will.”

“Let me make her comfortable,” the med said, and he was dispossessed even of that post–invited back again, to wash Pia’s body, to lift her, to help the med settle her into a waiting clean bed; and then the med took the table out, so it was himself alone with Pia.

“Jin,” Pia said, and he put his arm under her head and held her, still frightened, still thinking on the pleasure they had had and the cost it was to bring a born‑man into the world. Pia’s cost. He felt guilt, like bad tape; but it was not a question of tape: it was something built in, irreparable in what they were.

Then they did bring the baby back, and laid it in Pia’s arms; and he could not forbear to touch it, to examine the tininess of its hands, the impossibly little fists. It. Him. This born‑man.

xi

Year 2, day 189 CR

Children took their first steps in the second summer’s sun…squealed and cried and laughed and crowed. It was a good sound for a struggling colony, a sound which had crept on the settlement slowly through the winter, in baby cries and requisitions for bizarre oddments of supply. Baby washing hung out in the azi camp and the central domes in whatever sun the winter afforded–never cold enough to freeze, not through all the winter, just damp; and bonechilling nasty when the wind blew.

Gutierrez sat by the roadside, the road they had extended out to the fields. In one direction the azi camp fluttered with white flags of infant clothing out to dry; and in the other the crawlers and earthmovers sat, shrouded in their plastic hoods, and flitters nested there.

He watched–near where limestone blocks and slabs and rubble made the first solid azi buildings, one‑roomed and simple. They had left some chips behind, and an ariel was at its stone‑moving routine. It took the chips in its mouth, such as it could manage, and moved them, stacked them, in what began to look like one of the more elaborate ariel constructions, in the shadow of the wall.

A caliban had moved into the watermeadow again. They wanted to hunt it and Gutierrez left this to Security. He had no stomach for it. Best they hunt it now, before it laid eggs. But all the same the idea saddened him, like the small collection of caliban skulls up behind the main dome.

Barbaric, he thought. Taking heads. But the hunt had to be, or there would be more tunnelling, and the azi houses would fall.

He dusted himself off finally, started up and down the road toward the domes, having started the hunters on their way.

Man adjusted–on Gehenna, on Newport. Man gave a little. But between man and calibans, there did not look to be peace, not, perhaps, until the ship should come. There might be an answer, in better equipment. In the projection barriers they might have made work, if the weather had not been so destructive of equipment…if, if, and if.

He walked back into the center of camp, saw the Old Man sitting where he usually sat, under the canopy outside main dome. The winter had put years on the colonel. A stubble showed on his face, a spot of stain on his rumpled shirt front. He drowsed, did Conn, and Gutierrez passed him by, entered quietly into the dome and crossing the room past the long messtable, poured himself a cup of the ever‑ready tea. The place smelled of fish. The dining hall always did. Most all Gehenna smelled of fish.

He sat down, with some interest, at the table with Kate Flanahan. The special op was more than casual with him; no precise recollection where it had started, except one autumn evening, and realizing that there were qualities in Kate which mattered to him.

“You got it?” Kate asked.

“I headed them out. I don’t have any stomach left for that.”

She nodded. Kate trained to kill human beings, not wildlife. The specials sat and rusted. Like the machinery out there.

“Thought–” Gutierrez said, “I might apply for a walkabout. Might need an escort.”

Kate’s eyes brightened.

But “No,” Conn said, when he broached the subject, that evening, at common mess.

“Sir–”

“We hold what territory we have,” the colonel said. In that tone. And there was no arguing. Silence fell for a moment at the table where all of them who had no domestic arrangements took their meals. It was abrupt, that answer. It was decisive. “We’ve got all we can handle,” the colonel said then. “We’ve got another year beyond this before we get backup here, and I’m not stirring anything up by exploring.”

The silence persisted. The colonel went on with his eating, a loud clatter of knife and fork.

“Sir,” Gutierrez said, “in my professional opinion–there’s reason for the investigation, to see what the situation is on the other bank, to see–”

“We’ll be holding this camp and taking care of our operation here,” the colonel said. “That’s the end of it. That’s it.”

“Yes, sir,” Gutierrez said.

Later, he and Kate Flanahan found their own opportunity for being together, with more privacy and less comfort, in the quarters he had to himself, with Ruffles, who watched with a critical reptilian eye.

“Got a dozen specs going crazy,” Kate said during one of the lulls in their lovemaking, when they talked about the restriction, about the calibans, about things they had wanted to do. “Got people who came here with the idea we’d be building all this time. Special op hoped for some use. And we’re rotting away. All of us. You. Us. Everyone but the azi. The Old Man’s got this notion the world’s dangerous and he’s not letting us out of camp. He’s scared of the blamed lizards, Marco. Can’t you try it on a better day, make sense to him, talk sense into him?”

“I’ll go on trying,” he said. “But it goes deeper than just the calibans. He has his own idea how to protect this base, and that’s what he means to do. To do nothing. To survive till the ships come. I’ll try.”

But he knew the answer already, implicit in the Old Man’s clamped jaw and fevered stare.

“No,” the answer came when he did ask again, days later, after stalking the matter carefully. “Put it out of your head, Gutierrez.”

He and Flanahan went on meeting. And one day toward fall Flanahan reported to the meds that she might be pregnant. She came to live with him; and that was the thing that redeemed the year.

But Gutierrez’ work was slowed to virtual stop–with all the wealth of a new world on the horizon. He did meticulous studies of tiny ecosystems along the shoreline; and when in the fall another caliban turned up in the watermeadow, and when the hunters shot it, he stood watching the crime, and sat down on the hillside in view of the place, sat there all the day, because of the pain he felt.

And the hunters avoided his face, though there was no anger in his sitting there, and nothing personal.

“I’m not shooting any more,” a special op told him later, the man who had shot this one.

As for Flanahan, she had refused the hunt.

xii

Year 2, day 290 CR

The weather turned again toward the winter, the season of bitter cold rain and sometime fogs, when the first calibans wandered into the camp. And stayed the night. They passed like ghosts in the fog, under the haloed lights, came like the silly ariels; but the calibans were far more impressive.

Jin watched them file past the tent, strange and silent except for the scrape of leathery bodies and clawed feet; and he and Pia gathered little Jin against them in the warmth of the tent, afraid, because these creatures were far different than the gay fluttery green lizards that came and went among the tents and the stone shelters.

“They won’t hurt us,” Pia said, a whisper in the fog‑milky night. “The tapes said they never hurt anyone.”

“There was the captain,” Jin said, recalling that, thinking of all their safe tent tumbling down into some chasm, the way the born‑man Beaumont had died.

“An accident.”

“But born‑men shoot them.” He was troubled at the idea. He had never gotten it settled in his mind about intelligence, what animals were and what men were, and how one told the difference. They said the calibans had no intelligence. It was not in their gene‑set. He could believe that of the giddy ariels. But these were larger than men, and grim and deliberate in their movements.

The calibans moved through, and there were no human sounds, no alarms to indicate harm. But they laced the tentflap and stayed awake with little Jin asleep between them. At every small sound outside they started, and sometimes held hands in the absolute dark and closeness of the tent.

Perhaps, Jin thought in the lonely hours, the calibans were angry that born‑men hunted them. Perhaps that was why they came.

But on the next day, when they got up with the sun, a rumor of something strange passed through the camp, and Jin went among the others to see, how all the loose stones they had stacked up for building had been moved and set into a low and winding wall that abutted a building in which azi lived. He went to work with the others, undoing what the calibans had done, but he was afraid with an unaccustomed fear. Until then he had feared only born‑men, and known what right and wrong was. But he felt strange to be taking down what the calibans had done, this third and unaccountable force which had walked through their midst and noticed them.

“Stop,” a supervisor said. “People are coming from the main camp to see.”

Jin quit his work and sat down among the others, wrapped tightly in his jacket and sitting close to other azi…watched while important born‑men came from the main domes. They made photographs, and the born‑man Gutierrez came with his people and looked over every aspect of the building. This born‑man Jin knew: this was the one they called when they found something strange, or when someone had been stung or bitten by something or wandered into one of the nettles. And there was in this man’s face and in the faces of his aides and in the faces of no few of the other born‑men…a vast disturbance.

“They respond to instinct,” Gutierrez said finally. Jin could hear that much. “Ariels stack stones. The behavior seems to be wired into the whole line.”

But calibans, Jin thought to himself, built walls in the night, silently, of huge stones, and connected them to buildings with people in them.

He never felt quite secure after that, in the night, although the born‑men went out and strung electric fences around the camp, and although the calibans did not come back. Whenever the fogs would come, he would think of them ghosting powerfully through the camps, so still, so purposeful; and he would hug his son and Pia close and be glad that no azi had to be outside by night.

xiii

Year 3, day 120 CR

The air grew warmer again, and the waiting began…the third spring, when the ships should come. All the ills–the little cluster of forlorn human graves beside the sea–seemed tragedy on a smaller scale, against the wide universe, because the prospect of ships reminded people that the world was not alone. “When the ships come,” was all the talk in camp.

When the ships came, there would be luxuries again, like soap and offworld foods.

When the ships came, the earthmovers would move again, and they would build and catch up to schedule.

When the ships came, there would be new faces, and the first colonists would have a distinction over the newcomers, would own things and be someone.

When the ships came, there would be birthlabs and azi and the population increase would start tipping the balance on Gehenna in favor of man.

But spring wore on past the due date, with at first a fevered anticipation, and then a deep despair, finally hopes carefully fanned to life again; a week passed, a month–and When became a forbidden word.

Conn waited. His joints hurt him; and there would be medicines when the ship came. There would be someone on whom to rely. He thought of Cyteen again, and Jean’s untended grave. He thought of–so many things he had given up. And at first he smiled, and then he stopped smiling and retreated to his private dome. He still had faith. Still believed in the government which had sent him here, that something had delayed the ships, but not prevented them. If something were wrong, the ship would hang off in space at one of the jump points and repair it and get underway again, which might take time.

He waited, day by day.

But Bob Davies lay down to sleep one late spring night and took all the pills the meds had given him. It was a full day more before anyone noticed, because Davies lived alone, and all the divisions he usually worked had assumed he was working for someone else, on some other assignment. He had gone to sleep, that was all, quietly, troubling no one. They buried him next to Beaumont, which was all the note he had left wanted of them. It was Beaumont’s death that had killed Davies: that was what people said. But it was the failure of the ship that prompted it, whatever Davies had hoped for–be it just the reminder that Somewhere Else existed in the universe; or that he hoped to leave. Whatever hope it was that kept the man alive–failed him.

James Conn went to the funeral by the sea. When it was done, and the azi were left to throw earth into the grave, he went back to his private dome and poured himself one drink and several more.

A fog rolled in that evening, one of those fogs that could last long, and wrapped all the world in white. Shapes came and went in it, human shapes and sometimes the quiet scurryings of the ariels; and at night, the whisper of movements which might be the heavier tread of calibans–but there were fences to stop them, and most times the fences did.

Conn drank, sitting at the only real desk in Gehenna; and thought of other places: of Jean, and a grassy grave on Cyteen; on the graves by the sea; on friends from the war, who had had no graves at all, when he and Ada Beaumont had had a closeness even he and Jean had never had…for a week, on Fargone; and they had never told Jean and never told Bob, about that week the 12th had lost a third of its troops and they had hunted the resistance out of the tunnels pace by pace. He thought on those days, on forgotten faces, blurred names, and when the dead had gotten to outnumber the living in his thoughts he found himself comfortable and safe. He drank with them, one and all; and before morning he put a gun to his head and pulled the trigger.

xiv

Year 3, day 189 CR

The grain grew, the heads whitened, and the scythes went back and forth in azi hands, the old way, without machines; and still the ships delayed.

Gutierrez walked the edge of the camp, out near those fields, and surveyed the work. The houses at his right, the azi camp, were many of them of stone now, ramshackle, crazy building; but all the azi built their own shelters in their spare time, and sometimes they found it convenient to build some walls in common…less work for all concerned. If it stood, the engineers and the Council approved it; and that was all there was to it.

He and Kate did something of the like, needing room: they built onto their dome with scrap stone, and it served well enough for an extra room, for them and for small Jane Flanahan‑Gutierrez.

Another Caliban had come into the meadow. They came, Gutierrez reckoned, when the seasons turned, and whenever the autumn approached they were obsessed with building burrows. If thoughts at all proceeded in those massive brains. He argued with Council, hoping still for his expedition across the river; but it was weeding time; but it was harvest time. Now a caliban was back and he proposed studying it where it was.

And if it undermines the azi quarters, Gallin had objected, head of Council; or if it gets into the crops–

“We have to live here,” Gutierrez had argued, and said what no one had said in Council even yet: “So there’s not going to be a ship. And how long are we going to sit here blind to the world we live on?”

There was silence after that. He had been rude. He had destroyed the pretenses. There were sullen looks and hard looks, but most had no expression at all, keeping their terror inside, like azi.

So he went now, alone, before they took the guns and came hunting. He walked past the fields and out across the ridge and down, out of easy hail of the camp, which was against all the rules.

He sat down on the side of the hill with his glasses and watched the moundbuilders for a long time…watched as two Calibans used their blunt noses and the strength of their bodies to heave up dirt in a ridge.

About noon, having taken all the notes of that sort he wanted, he ventured somewhat downslope in the direction of the mound.

Suddenly both dived into the recesses of their mound.

He stopped. A huge reptilian head emerged from the vent on the side of the mound. A tongue flicked, and the whole caliban followed, brown, twice the size of the others, with overtones of gold and green.

A new kind. Another species…another gender, there was no knowing. There was no leisure for answers. All they knew of calibans was potentially overturned and they had no way to learn.

Gutierrez took in his breath and held it. The brown–six, maybe eight meters in length–stared at him a while, and then the other two, the common grays, shouldered past it, coming out also.

That first one walked out toward him, closer, closer until he stared at it in much more detail than he wanted. It loomed nearly twice a man’s height. The knobby collar lifted, flattened again. The other two meanwhile walked toward the river, quietly, deliberately, muddy ghosts through the tall dead grass. They vanished. The one continued to face him for a moment, and then, with a sidelong glance and a quick refixing of a round‑pupilled eye to be sure he still stood there…it whipped about and fled with all the haste a caliban could use.

He stood there and stared a moment, his knees shaking, his notebook forgotten in his hand, and then, because there was no other option, he turned around and walked back to the camp.

That night, as he had expected, Council voted to hunt the Calibans off the bank; and he came with them in the morning, with their guns and their long probes and their picks for tearing the mound apart.

But there was no caliban there. He knew why. That they had learned. That all along they had been learning, and their building on this riverbank was different than anywhere else in the world–here, close to humans, where calibans built walls.

He stood watching, refusing comment when the hunters came to him. Explanations led to things the hunters would not want to hear, not with the ships less and less likely in their hopes.

“But they didn’t catch them,” Kate Flanahan said that night, trying to rouse him out of his brooding. “It failed, didn’t it?”

“Yes,” he said. And nothing more.

xv

Year 3, day 230 CR

“Jin,” the elder Jin called; and Pia called with him, tramping the aisles and edges of the camp. Fear was in them…fear of the outside, and the chance of calibans. “Have you seen our son?” they asked one and another azi they met. “No,” the answer was, and Pia fell behind in the searching as Jin’s strides grew longer and longer, because Pia’s belly was heavy with another child.

The sun sank lower in the sky, and they had gone much of the circuit of the camp, out where the electric fence was. That riverward direction was young Jin’s fascination, the obsession of more than one of the rowdy children in the camp.

“By the north of the camp,” an azi told him finally, when he was out of breath and nearly panicked. “There was some small boy playing there.”

Jin went that way, jogging in his haste.

So he found his son, where the walls stopped and the land began to slope toward the watermeadow. White slabs of limestone were the last wall there, the place they had once stacked the building stone. And little Jin sat in the dirt taking leftover bits of stone and piling them. An ariel assisted, added pebbles to the lot–turned its head and puffed up its collar at so sudden an approach.

“Jin,” Jin senior said. “Look at the sun. You know what I told you about wandering off close to dark. You know Pia and I have been hunting for you.”

Little Jin lifted a face which was neither his nor Pia’s and looked at him through a mop of black hair.

“You were wrong,” Jin said, hoping that his son would feel shame. “We thought a caliban could have gotten you.”

His son said nothing, made no move, like the ariel.

Pia arrived, out of breath, around the white corner of the last azi house. She stopped with her hands to her belly, cradling it, her eyes distraught. “He’s all right,” Jin said. “He’s safe.”

“Come on,” Pia said, shaken still. “Jin, you get up right now and come.”

Not a move. Nothing but the stare.

Jin elder ran a hand through his hair, baffled and distressed. “They ought to give us tapes,” he said faintly. “Pia, he wouldn’t be like this if the tape machines worked.”

But the machines were gone. Broken, the supervisors said, except one, that the born‑men used for themselves.

“I don’t know,” Pia said. “I don’t know what’s right and wrong with him. I’ve asked the supervisors and they say he has to do these things.”

Jin shook his head. His son frightened him. Violence frightened him. Pick him up and spank him, the supervisors said. He had hit his son once, and the tears and the noise and the upset shattered his nerves. He himself had never cried, not like that.

“Please come,” he said to his son. “It’s getting dark. We want to go home.”

Little Jin carefully picked up more stones and added them to his pattern, the completion of a whorl. The ariel waddled over and moved one into a truer line. It was all loops and whorls, like the ruined mounds that came back year by year in the meadow.

“Come here.” Pia came and took her son by the arms and pulled him up, scattering the patterns. Little Jin kicked and screamed and tried to go on sitting, which looked apt to hurt Pia. Jin elder came and picked his son up bodily under one arm, nerving himself against his screams and his yells, impervious to his kicking as they carried him in shame back to the road and the camp.

While their son was small they could do this. But he was growing, and the day would come they could not.

Jin thought about it, late, lying with Pia and cherishing the silence…how things had gone astray from what the tapes had promised, before the machines had broken. The greatest and wisest of the born‑men were buried over by the sea, along with azi who had met accidents; the ships were no longer coming. He wished forlornly to lie under the deepteach and have the soothing voice of the tapes tell him that he had done well.

He doubted now. He was no longer sure of things. His son, whom sometimes they loved, who came to them and hugged them and made them feel as if the world was right again, had contrary thoughts, and strayed, and somehow an azi was supposed to have the wisdom to control this born‑man child. Sometimes he was afraid–of his son; of the unborn one in Pia’s belly.

When the ship comes, the azi used to say.

But they stopped saying that. And nothing was right since.

IV

THE SECOND

GENERATION

Military Personnel:

Col. James A. Conn, governor general, d. 3 CR

Capt. Ada P. Beaumont, It. governor, d. year of founding

Maj. Peter T. Gallin, personnel

M/Sgt. Ilya V. Burdette, Corps of Engineers

Cpl. Antonia M. Cole

Spec. Martin H. Andresson

Spec. Emilie Kontrin

Spec. Danton X. Norris

M/Sgt. Danielle L. Emberton, tactical op.

Spec. Lewiston W. Rogers

Spec. Hamil N. Masu

Spec. Grigori R. Tamilin

M/Sgt. Pavlos D. M. Bilas, maintenance

Spec. Dorothy T. Kyle

Spec. Egan I. Innis

Spec. Lucas M. White

Spec. Eron 678‑4578 Miles

Spec. Upton R. Patrick

Spec. Gene T. Troyes

Spec. Tyler W. Hammett

Spec. Kelley N. Matsuo

Spec. Belle M. Rider

Spec. Vela K. James

Spec. Matthew R. Mayes

Spec. Adrian C. Potts

Spec. Vasily C. Orlov

Spec. Rinata W. Quarry

Spec. Kito A. M. Kabir

Spec. Sita Chandrus

M/Sgt. Dinah L. Sigury, communications

Spec. Yung Kim

Spec. Lee P. de Witt

M/Sgt. Thomas W. Oliver, quartermaster

Cpl. Nina N. Ferry

Pfc. Hayes Brandon Lt. Romy T. Jones, special forces

Sgt. Jan Vandermeer

Spec. Kathryn S. Flanahan

Spec. Charles M. Ogden

M/Sgt. Zell T. Parham, security

Cpl. Quintan R. Witten

Capt. Jessica N. Sedgewick, confessor‑advocate

Capt. Bethan M. Dean, surgeon

Capt. Robert T. Hamil, surgeon

Lt. Regan T. Chiles, computer services

Civilian Personnel:

Secretarial personnel: 12

Medical/surgical: 1

Medical/paramedic: 7

Mechanical maintenance: 20

Distribution and warehousing: 20

Robert H. Davies d. CR 3

Security: 12 Computer service: 4

Computer maintenance: 2

Librarian: 1

Agricultural specialists: 10