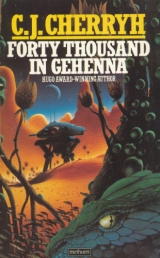

Текст книги "Forty Thousand in Gehenna"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

There were some braver than the others–a female face startlingly naked without brows, a too‑thin mouth that twisted into a struggling grin; a darkskinned man who looked less naked, who shouted out a cheer that shocked the silence. Another reached up and rubbed the tattoo on his cheek; but that would have to wear off, as the hair would have to grow back. “You’re Hill?” Gutierrez asked of his assigned roommate. “What field?”

The thin, older man blinked, wiped a hand over his shaved skull. “Ag specialist.”

“I’m biology,” Gutierrez said. “Not a bad mix.”

Others talked, a sudden swelling of voices; and someone swore, which was what Gutierrez wanted to do, to break the rest of the restraints, to vent what had been boiling up for three long days. But the words refused to come out, and he walked on with Hill–26, 24, the whole string down past the crosscorridor and around the corner: 16, 14, 12… He jammed the keycard in with a hand shaking like palsy, opened the door on an ordinary little cabin with twin bunks and colors, cheerful green and blue colors. He stood inside and caught his breath, then sat down on the bed and dropped his head into his hands, even then feeling the tiny prickle of stubble under his fingertips. He felt grotesque. He remembered every mortifying detail of his progress across the docks; and the lines; and the medics; and the tape labs and the rest of it.

“How old are you?” Hill asked. “You look young.”

“Twenty two.” He lifted his head, shivering on the verge of collapse. If it had been a friend with him, he might have, but Hill was holding on the same way, quietly. “You?”

“Thirty eight. Where from?”

“Cyteen. Where from, yourself?”

“Wyatt’s.”

“Keep talking. Where’d you study?”

“Wyatt’s likewise. What about you? Ever been on a ship before?”

“No.” He hypnotized himself with the rhythm of question and answer…got himself past the worst of it. His breathing slowed. “What’s an ag man doing on a station?”

“Fish. Lots of fish. Got similar plans where we’re going.”

“I’m exobiology,” Gutierrez said. “A whole new world out there. That’s what got me.”

“A lot of you young ones,” Hill said. “Me–I want a world. Any world. The passage was free.”

“Hang, we just paid for it.”

“I think we did,” Hill said.

And then the swelling in his throat caught Gutierrez by surprise and he bowed his head into his hands a second time and sobbed. He fought his breathing back to normal–looked up to find Hill wiping his own eyes, and swallowed the shamed apology he had had ready. “Physiological reaction,” he muttered.

“Poor bastards,” Hill said, and Gutierrez reckoned what poor bastards Hill had in mind. There were real azi aboard, who went blankly to their berths wherever they might be, down in the holds–who would go on being silent and obedient whatever became of them, because that was what they were taught to be.

Lab specialists would follow them in three years, Gutierrez knew, who would bring equipment with which the new world could make its own azi; and the lab techs would come in expecting the fellowship of the colony science staff. But they would get none from him. Nothing from him. Or from the rest of them–not so easily.

“The board that set this up,” Gutierrez said quietly, hoarsely, “they can’t have any idea what it’s like. It’s crazy. They’re going to get people crazy like this.”

“We’re all right,” Hill said.

“Yes,” he said; but it was an azi’s answer, that sent a chill up his back. He clamped his lips on it, got up and walked the few paces the room allowed, because he could now; and it still felt unnatural.

vi

T‑12 hours

Aboard Venture

docked at Cyteen Station

“Beaumont.” Conn looked up from his desk as the permission‑to‑enter button turned up his second in command. He rose and offered his hand to the special forces captain and her husband. “Ada,” he amended, for old times’ sake. “Bob. Glad to draw the both of you–” He was always politic with the spouses, civ that Bob Davies was. “Just make it in?”

“Just.” Ada Beaumont sighed, settled, and took a seat. Her husband took one by her. “They pulled me from Wyatt’s and I had a project finishing up there…then it was kiting off to Cyteen on a tight schedule to take the tapes I guess you had. They just shuttled us up, bag and baggage.”

“Then you know the score. They put you somewhere decent for quarters?”

“Two cabins down. A full suite: can’t complain about that.”

“Good.” Conn leaned back, shifted his eyes to Bob Davies. “You have a mission slot in Distributions, don’t you?”

“Number six.”

“That’s good. Friendly faces–Lord, I love the sight of you. All those white uniforms…” He looked at the pair of them, recalling earlier days, Cyteen on leave, Jean with him… Jean gone now, and the Beaumont‑Davies sat here, intact, headed out for a new world. He put on a smile, diplomat, because it hurt, thinking of the time when there had been four of them. And Davies had to survive. Davies, who lived his life on balance books and had no humor. “At least,” he said charitably, “faces from home.”

“We’re getting old,” Beaumont said. “They all look so young. About time we all found ourselves a berth that lasts.”

“Is that what drew you?”

“Maybe,” Beaumont said. Her seamed face settled. “Maybe there’s about one more mission left in us, and one world’s about our proper size about now. Never had time for kids, Bob and me. The war–You know. So maybe on this one there’s something to build instead of blow up. I like to think…maybe some kind of posterity. Maybe when they get the birthlabs set up–maybe–no matter what the gene‑set is; I mean, we’d take any kid, any they want to farm out. Missed years, Jim.”

He nodded somberly. “They give us about a three year lag on the labs, but when that lab goes in, you’re first in line, no question.–Can I do anything for you in settling in? Everything the way it ought to be?”

“Hang, it’s great, nice modern ship, a suite to ourselves–I figure I’ll take a turn down there and see where they’re stacking those poor sods below. Anyone I know down there?”

“Pete Gallin.”

“No. Don’t know him.”

“All strange faces. We’re up to our ears in brighteyed youth, a lot of them jumped up to qualify them…a lot of specs out of the state schools and no experience…a few good noncoms who came up the hard way. Some statistician, fry him, figured that was the best mix in staff; and we’ve got the same profile in the civ sector, but not so much so. A lot of those have kin elsewhere, but they know there’s no transport back; blind to everything else but their good luck, I suppose. Or crazy. Or maybe some of them don’t mind mud and bugs. Freshfaced, the lot of them. You want kids, Beaumont, we’ve got kids, no question about it. The whole command’s full of kids. And we’ll lose a few.”

A silence. Davies shifted uncomfortably. “We’re going to get rejuv out there, aren’t we? They said–”

“No question. Got us rejuv and some crates of Cyteen’s best whiskey. And soap. Real soap, this time, Ada.”

She grinned, a ghost out of the tunnels and the deeps of Fargone, the long, long weeks dug in. “Soap. Fresh air, sea and river to fish–can’t ask better, can we?”

“And the neighbors,” Davies said. “We’ve got neighbors.”

Conn laughed, short and dry. “The lizards may contest you for the fish, but not much else. Unless you mean Alliance.”

Davies’ face had settled into its habitual dour concern. “They said there wasn’t a likelihood.”

“Isn’t,” Beaumont said.

“They said–”

“Alliance might even know what we’re up to,” Conn said… Davies irritated him: discomfiting the man satisfied him in an obscure way. “I figure they might. But they’ve got to go on building their ships, haven’t they? They’ve got the notion to set something up with Sol, that’s where their eyes are at the moment.”

“And if that link‑up with Sol does come about–then where are we?”

“Sol couldn’t finance a dockside binge. It’s all smoke.”

“And we’re sitting out there–”

“I’ll tell you something,” Conn said, leaned on his desk, jabbed a finger at them. “If it isn’t smokescreen, they swallow our new little colony. But they’re all hollow. Alliance is all trade routes, just a bunch of merchanters, no worlds to speak of. They don’t care about anything else at the moment…and by the time they do, they’re pent in. We might be fighting where we’re going, give or take a generation–but don’t expect any support. That’s not the name of what we’re doing out there. If they swallow us, they swallow us. And if they swallow too many of us, they’ll find they’ve swallowed something Alliance can’t digest. Union’s going to be threaded all through them. That’s what we’re going out there for. That’s why the whole colonial push.”

Davies looked at his wife. A crease deepened between his eyes.

“Jim isn’t only special op,” Beaumont said, “he’s out of the Praesidium. And it doesn’t hurt to know that…in closed company. I have–for the past half dozen years. That’s why Jim always got transferred to the hot spots. Isn’t it, Jim?”

Conn shrugged, vexed–then thinking it was the truth, that there was no more cover, no more of anything that mattered. “Jim’s getting to be an old man, that’s all. It looked like a good assignment. My reasons are like yours. Just winding down. Finding something to do. Praesidium asked. This is a retirement job. I’ve got a good staff. That’s all I ask.”

So they were on their way, he thought when he had packed Beaumont and Davies off, Beaumont to a tour below and Davies to his unpacking and settling in. They were sealed in, irrevocably. Venturewould use an outbound vector decidedly antiterrene, as if she and her companion ships had a destination on the far side of Union space instead of the outlying border region which was their real object; she had a false course filed at Cyteen Station for the obstinately curious.

So the auxiliary personnel, military and otherwise, found their way aboard among azi workers; and military officers chanced aboard as if they were simply hopping transport, common enough practice.

It was all very smooth. No mission officer took official charge of anything public; it was all Venturepersonnel down there on the docks seeing the azi aboard, and seeing to the lading of boxes labeled for the Endeavor mines.

The clock pulsed away, closer and closer to undock.

II

THE VOYAGE

OUT

Military Personnel:

Col. James A. Conn, governor general

Capt. Ada P. Beaumont, It. governor

Maj. Peter T. Gallin, personnel

M/Sgt. Ilya V. Burdette, Corps of Engineers

Cpl. Antonia M. Cole

Spec. Martin H. Andresson

Spec. Emilie Kontrin

Spec. Danton X. Morris

M/Sgt. Danielle L. Emberton, tactical op.

Spec. Lewiston W. Rogers

Spec. Hamil N. Masu

Spec. Grigori R. Tamilin

M/Sgt. Pavlos D. M. Bilas, maintenance

Spec. Dorothy T. Kyle

Spec. Egan I. Innis

Spec. Lucas M. White

Spec. Eron 678‑4578 Miles

Spec. Upton R. Patrick

Spec. Gene T. Troyes

Spec. Tyler W. Hammett

Spec. Kelley N. Matsuo

Spec. Belle M. Rider

Spec. Vela K. James

Spec. Matthew R. Mayes

Spec. Adrian C. Potts

Spec. Vasily C. Orlov

Spec. Rinata W. Quarry

Spec. Kito A. M. Kabir

Spec. Sita Chandrus

M/Sgt. Dinah L. Sigury, communications

Spec. Yung Kim

Spec. Lee P. de Witt

M/Sgt. Thomas W. Oliver, quartermaster

Cpl. Nina N. Ferry

Pfc. Hayes Brandon

Lt. Romy T. Jones, special forces

Sgt. Jan Vandermeer

Spec. Kathryn S. Flanahan

Spec. Charles M. Ogden

M/Sgt. Zell T. Parham, security

Cpl. Quintan R. Witten

Capt. Jessica N. Sedgewick, confessor‑advocate

Capt. Bethan M. Dean, surgeon

Capt. Robert T. Hamil, surgeon

Lt. Regan T. Chiles, computer services

Civilian Personnel: to be assigned:

Secretarial personnel: 12

Medical/surgical: 1

Medical/paramedic: 7

Mechanical maintenance: 20

Distribution and warehousing: 20

Robert H. Davies

Security: 12

Computer service: 4

Computer maintenance: 2

Librarian: 1

Agricultural specialists: 10

Harold B. Hill

Geologists: 5

Meteorologist: 1

Biologists: 6

Marco X. Gutierrez

Education: 5

Cartographer: 1

Management supervisors: 4

Biocycle engineers: 4

Construction personnel: 150

Food preparation specialists: 6

Industrial specialists: 15

Mining engineers: 2

Energy systems supervisors: 8

TOTAL MILITARY 45

TOTAL CIVILIAN SUPERVISORY 296

TOTAL CITIZEN STAFF 341; TOTAL NONASSIGNED DEPENDENTS: 111; TOTAL ALL CITIZENS: 452

ADDITIONAL NONCITIZEN PERSONNEL:

“A” class: 2890

Jin 458‑9998

Pia 89‑687

“B” class: 12389

“M” class: 4566

“P” class: 20788

“V” class: 1278

TOTAL ALL NONCITIZENS: 41911

TOTAL ALL MISSION: 42363

Male/female ratio approx. 55%/45%

i

T‑00:15:01

Communication: Cyteen Dock HQ

CYTDOCK1/USVENTURE/USCAPABLE/USSWIFT/STANDBY UNDOCK.

T‑00:2:15

CYTDOCK1/USVENTURE/YOU ARE NUMBER ONE FOR DEPARTURE.

T‑00:0:49

USVENTURE/CYTDOCK1/SEQUENCE INITIATED/THANK YOU

STATIONMASTER/HOSPITALITY APPRECIATED/ENDIT.

ii

T00:0:20

Venture; en route

They moved. The stress made itself felt, and in spite of the tapes which had instructed them how all this would be, Jin 458 felt the shudder and shift of weight through the thousands of bodies jammed into the aisles of the bunks–stacks of bunks which leaned crazily together like watchtowers, stacks already filled with bodies, azi all crowded up together and holding onto each other as they had been told to do. In spite of all the instruction, Jin felt afraid, deep inside, not letting it out. A sigh went up, one united breath, when the weight stopped and they had the falling‑sensation again.

“Hold tight,” a voice told them over public address, and they held, a painful clenching of hands on shoulders and on the frames of the bunks and whatever they could hold to, so that they would not come drifting loose when the weight came back again.

And come it did, with a crash and rumble of machinery, an authoritative settling of feet firmly back to the floor and of clothes on bodies, a kind of crawling sensation far from pleasant.

“That’s it,” the PA told them. “We have G now. You can let go and find your places. You’re berthed by alphabetic and numeric sequence. If you can’t find your bunk, report to the door where you came in.”

Jin stood still waiting as the press of bodies slowly sorted itself out, until it became possible to move again, and people who had been jammed into the bunks were coming down the ladders to find their proper places. He could see a tag where he was, bunk M 234‑6787.

“The center aisle,” the PA voice said again, “is M 1 through M 7. Row two spinward is M 8 through N 1…”

Jin listened, shrank aside as azi needed to pass him to get to their places. So they were bunked by alphabet and birth‑order, not by gene‑set. He would not be near his sibs. It was all very confusing, but they were being told what to do and it was all, he supposed, moving with considerable organization under the circumstances.

It was hard to hold on with the ship moving as it was and people stumbled into him, thrown by the movement and the floor curve. Everyone hurried, at the pace of the PA voice, which kept throwing instructions at them. He reasoned that if MNO was spinward of the aisle, then J had to be the other direction, and when he had a clear space he went, handing his way along the bunk rails and not letting go, along aisles and past rows until he had come to a K and turned toward the front of the ship. He found himself among J designations, to his relief, and he kept searching, as others did, having figured out the system, passing muddled wanderers who were probably under T class, unable to read.

He located it–refuge, berth J 458‑9998, right on the bottom, so that he would not have to climb the ladders which towered up and up atilt in the eerie slantwise way that things were built on the curved floor of the ship. If he sat up on top, he thought, he could look straight into the chasms of other rows sideways to his floor. It was that huge a room and that much curve; and he was glad not to have that view. He sat down at his assigned place, feet over the edge; and all at once another of the J’s showed up. This J, another 458 but of gene‑set 8974–must come from some other farm, but he could not be sure with the shaving. The man clambered up the ladder over him and the bunk next upstairs gave slightly as his bunkmate climbed in and swung his feet over the edge. Jin sat still, bent over because of the low overhead. He was tired, very glad to sit down, and he felt a great deal safer enclosed by the four uprights and other groundlevel bunks all around him. Another J found the bunk at his head, which was more company; and more Js went up the ladder.

It was all going very fast now, with comforting efficiency: they had managed to do it all right. Soon people were sitting all about him. Someone took the other decklevel bunk next to his, and he saw people on either side, and facing him and angling away down the diagonal view through the uprights. The room was getting quiet again, even the nonreaders having mostly found their places, so that the PA sounded even louder. He had already spotted the small packet the PA told them about next, the plastic case lying on the pillow, and there was a massive stirring as thousands of azi reached and took theirs as he did–as they opened the covers and found hygiene kits and schedules.

“Read your schedule for exercise,” the voice instructed them. “If you don’t read, you will have a blue card or a red card. Blues are group one. Reds are group two. I will call you by those numbers; you will have half an hour at a time.”

It was not much time. Jin was already plotting how he could adjust his personal routine to follow it. There were more instructions, where one went for elimination and how one reported malaise, and instruction that they must sit or lie in the bunks at all other times because there was no room for people to walk about. “A great deal of the time we will play tape,” the voice promised them, which cheered Jin considerably.

He felt uncertain what his life had meant up to this point. He remembered well enough. But the importance he had attached to things was all revised. His life now seemed more preparatory than substantive. He looked forward to things to come. There would be a world, he believed; and he was called on to build it. He would become more and more like a born‑man and he would be on this assignment for the rest of his life, one of the most important assignments even born‑men hoped to get. All of this was due to his good fortune in having been born in the right year, on the right world, of the right gene‑set, and of course it was due to his excellent attention to his work. There would be only good tape for him, and when he had gotten where he was going, when he looked about him at a new land, there were certain things which would have to be done at once, with all the skill he had. People believed in him. They had chosen him. He was very happy, now that all the disturbing things were over, now that he could sit in his own bunk and know that he was safe…and he would have just about enough time to understand it all before they would be there, so the tape promised.

There would be Pia, for instance. He would have liked to have found Pia in all this crowd, and asked her whether the tape had talked to her about him. But he thought that it had. Usually they were very thorough about such details. And likely they had known even what he would answer: perhaps their own supervisor had had a hand in it, reaching out to take care of them, however far they had come from their beginnings. He and Pia would make born‑men together and the tape said that this would be as good as the reward tapes, a reward anytime they liked as long as they were off duty. He had a great deal of new information in that regard to think on, and information about the world they were going to, and lists of new rules and procedures. He wanted to succeed in this new place and impress his supervisors.

The PA finished instructing them. They were to lie flat on their bunks, and soon they would be asked to take trank from the ampoules given them in their personal kit. He arranged all this where he could find it, taped the trank series to the bedpost, and lay down as he was supposed to do, his head on his hands. He would be very busy for the future. He was scheduled for exercise in the 12th group, and when it was called, he wanted to proceed to the right place as quickly as possible and to plan a routine which would do as much as possible for him in the least amount of time.

He had never been so taut‑nerved and full of purpose–never had so much to look forward to, or even imagined such opportunity existed. He loved the state which first ordered his creation and now bought his contract and saw to every detail of his existence. It created Pia and all the others and took them together to a new world it planned to give them. Into the bargain it had made him strong and beautiful and intelligent, so that it would be proud of him. It felt very good to be what he was planned to be, to know that everything was precisely on schedule and that his contractholders were delighted with him. He tried very hard to please, and he felt a tingling of pleasure now that he knew he had done everything right and that they were on their way. He smiled and hugged it all inside himself, how happy he was, a preciousness beyond all past imagining.

A tape began. It talked about the new world, and he listened.

iii

T00:21:15

Venture log

“…outbound at 0244 m in good order. Estimate jump at 1200 a. All personnel secure under normal running. US Swiftand US Capablein convoy report 0332 m all stable and normal running.”

iv

T28 hours Mission Apparent Time

From the personal journal of Robert Davies

“…9/2/94. Jump completed. Four days to bend a turn after dump and we’re through this one. Out of trafficked space. We’re coming to our intended heading and now the worst part begins. Four more of these–this time without proper charts. I never liked this kind of thing.”

v

T15 days MAT

Lounge area 2, US Venture

“That’s clear on the checks,” Beaumont said, and Gutierrez, among other team chiefs, nodded. “All equipment accounted for. Venture’s been thorough. Nothing damaged, nothing left. The governor–you can call him governor from now on–wants a readiness report two days after third jump. Any problem with that?”

A general shaking of heads, among the crowd of people, military and civilian, present in the room. They filled it. It was not a large lounge; they were crowded everywhere, and the bio equipment was accessible only in printout from Swift, which swore it had been examined, that the cannisters were intact and the shock meters showed nothing disastrous. More of their hardware rode on Swiftand Capablethan on Venture. They could get at nothing. It was a singularly frustrating time–and after two weeks mission apparent time it was still humiliating to sit in the presence of military officers or ship’s crew, who had never gone through the shaving, who had no idea of the thing that bound them together, who had.

And when it broke up, when Beaumont walked out, grayhaired and venerable and with her sullen special op bearing, there was a silence.

A moving of chairs then. “Game in R15,” one of the regs said. “All welcome.”

“Game in 24,” a civ said. “40,” another added. It was what they did to pass the time. There was a newsletter, passed by hand and not on comp, which told who won what, and in what game; and that was what they did for their sanity. They paid off in favor points. This was a reg, a military custom:–because where we been, Matt Mayes put it, ain’t no surety we get free cash; but favor points, that’s a loan of something or a walk after something or whatever: no sex, no property, no tours, no gear–cut your throat if you play for solid stakes. Favor points is friendly. Don’t you get in no solid game: don’t you bet no big favors. You’re safe on favor points. You do the other thing, the Old Man’ll collect all bets and shut down the games, right?

Got us reg civs, was the way the regs put it. They’re reg civs, meaning the line was down and the regs, the military, swept them into the games and the bets and otherwise included them. And it was a strange feeling, that all their pride came from the stiff‑backboned regs, like Eron Miles, whose tattooed number was real, because he came out of the labs, who recovered his bearings as fast as any of them whose numbers were wearing dim. It was We; and the officers and the governor were They. That was the way of it.

And even further removed was the spacer crew–who gambled too, for credits, in other games, because their voyage was a roundtrip and they would go on and on doing missions like this. The spacers pushed odds–even following the route a probeship crew had laid out for them, themselves following a drone probe: Venturewent with navigational records and all the amenities, but it was a nervous lot of spacers all the same, and none of the games mixed–Wouldn’t gamble with you, the conversation was reported between spacer and reg: Cheap stakes.

People remembered the room numbers, with the manic attention they deserved, because it was the games that took one’s mind off an approaching jump–that let them forget for a while that they were travelling a scarcely mapped track that had the spacers hairtriggered and locked in their own manic gamblings.

Cheap at any price, that little relaxation, that little forgetting. One forgot the hazards, forgot the discomforts to come, forgot to imagine, which was the worst mistake of all.

There were assignations, too: room shiftings and courtesies–for the same reasons, that with life potentially short, sex was a stimulus powerful enough to wipe out thinking. And liquor was strictly rationed.

It took a cultivated eye to discover the good points of any of them at the moment, but it was appreciated all the more when it happened.

vi

T20 days MAT

Number two hold, Venture

It was duty, to walk the holds–inspecting what was at hand, because so much of the mission was elsewhere, under other eyes, on the other ships. Conn bestirred himself in the slow days of transit between jumps–surprised the troops and civilians under his authority with inspections; and visited those reeking holds where the azi slept and ate and existed, in stacked berths so close together they formed canyons towering twenty high in places, the topmost under the glare of lights and the direct rush of the ventilating fans and the nethermost existing in the dark of the canyons where the air hardly stirred. All the bunks were filled with bodies, such small spaces that no one could sit upright in them without sitting on the edge and crouching, which some did, perhaps to relieve cramped muscles…but they never stirred out of them except with purpose. The hold stank of too many people, stank of chemicals they used to disinfect and chemicals they used in the lifesupport systems which they had specially rigged to handle the load. The stench included cheap food, and the effluvia of converter systems which labored to cope with the wastes of so large a confined group. The room murmured with the sound of the fans, and of the rumbling of the cylinder round the core, a noise which pervaded all the ship alike; and far, far softer, the occasional murmur of azi voices. They talked little, these passengers; they exercised dutifully in the small compartment dedicated to that purpose, just aft of the hold; and dutifully and on schedule they returned to their bunks to let the next scheduled group have the open space, their sweating bodies unwashed because the facilities could not cope with so many.

Cloned‑men, male and female. So was one of the specs with the mission, lab‑born; and that was no shame, simply a way of being born. Tape‑taught, and that was no shame either: so was everyone. The deep‑teach machines were state of the art in education. They poured the whole of the universe in over chemically lowered thresholds, while the mind sorted out what it was capable of keeping, without exterior distractions or the limitations of sight or hearing.

But the worker tapes were something else. Worker tapes created the like of these, row on row of expressionless faces staring at the bottom of the bunk above them day after day–male and female, bunked side by side without difficulty, because they presently lacked desires. They regarded their bodies as valuable and undivertible from their purpose, the printout said regarding them. They would receive more information in transit–the PA blared with silken tones, describing the world they were going to. And there were tapes to give them when they had landed–tapes for all of them, for that matter. Tapes for generations to come.

He walked through–into the exercise area, unnoticed, where hundreds of azi worked in silence. Their exercise periods, in which crew or troops might have laughed and talked or worked in the group rhythms that pulled a military unit’s separate minds into one–were utterly narcissistic, a silent, set routine of difficult stretchings and manipulations and calisthenics, with fixed and distant stares or pensive looks. No talk. No notice of an inspecting presence.

“You,” he said to one taller and handsomer than the average of these tall, handsome people, and the azi stopped in his bending and straightened, an immediate, flowerlike focussing of attention. “How are you getting along?”

“Very well, sir.” The azi breathed hard from his exertions. “Thank you.”

“Name?”

“Jin, sir; 458‑9998.”

“Anything needed?”

“No, sir.” The dark eyes were bright and interested, a transformation. “Thank you.”

“You feel good, Jin?”

“Very good, sir, thank you.”

He walked back the way he had come–looked back, but the azi had resumed his exercises. They were like that. Azi had always made him uncomfortable, possibly because they were not unhappy. It said something he had no wish to hear. Erasable minds…the azi; if anything upset them, the tapes could take it away again.

And there were times he would have found it good to have peace like that.

He passed through the hold again, unnoticed. They were undeniably a group, the azi, like the rest of the mission topside. They maintained themselves as devotedly as they would maintain anything set in their care, and their eyes were set on a rarely disturbed infinity, like waking sleep.