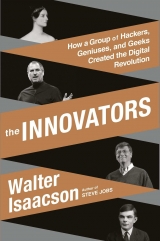

Текст книги "The Innovators: How a Group of Inventors, Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution"

Автор книги: Walter Isaacson

Жанр:

Биографии и мемуары

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 42 страниц)

Alan Kay (1940– ) at Xerox PARC in 1974.

Kay’s 1972 sketch for a Dynabook.

Lee Felsenstein (1945– ).

The first issue, October 1972.

By keeping children (of all ages) in mind, Kay and his colleagues advanced Engelbart’s concepts by showing that they could be implemented in a manner that was simple, friendly, and intuitive to use. Engelbart, however, did not buy into their vision. Instead he was dedicated to cramming as many functions as possible into his oNLine System, and thus he never had a desire to make a computer that was small and personal. “That’s a totally different trip from where I’m going,” he told colleagues. “If we cram ourselves in those little spaces, we’d have to give up a whole bunch.”70 That is why Engelbart, even though he was a prescient theorist, was not truly a successful innovator: he kept adding functions and instructions and buttons and complexities to his system. Kay made things easier, and in so doing showed why the ideal of simplicity—making products that humans find convivial and easy to use—was central to the innovations that made computers personal.

Xerox sent Alto systems to research centers around the country, spreading the innovations dreamed up by PARC engineers. There was even a precursor to the Internet Protocols, the PARC Universal Packet, that allowed different packet-switched networks to interconnect. “Most of the tech that makes the Internet possible was invented at Xerox PARC in the 1970s,” Taylor later claimed.71

As things turned out, however, although Xerox PARC pointed the way to the land of personal computers—devices you could call your own—the Xerox Corporation did not lead the migration. It made two thousand Altos, mainly for use in Xerox offices or affiliated institutions, but it didn’t market the Alto as a consumer product.II “The company wasn’t equipped to handle an innovation,” Kay recalled. “It would have meant completely new packaging, all new manuals, handling updates, training staff, localizing to different countries.”72

Taylor recalled that he ran into a brick wall every time he tried to deal with the suits back east. As the head of a Xerox research facility in Webster, New York, explained to him, “The computer will never be as important to society as the copier.”73

At a lavish Xerox corporate conference in Boca Raton, Florida (where Henry Kissinger was the paid keynote speaker), the Alto system was put on display. In the morning there was an onstage demo that echoed Engelbart’s Mother of All Demos, and in the afternoon thirty Altos were set up in a showroom for everyone to use. The executives, all of whom were male, showed little interest, but their wives immediately started testing the mouse and typing away. “The men thought it was beneath them to know how to type,” said Taylor, who had not been invited to the conference but showed up anyway. “It was something secretaries did. So they didn’t take the Alto seriously, thinking that only women would like it. That was my revelation that Xerox would never get the personal computer.”74

Instead, more entrepreneurial and nimble innovators would be the first to foray into the personal computer market. Some would eventually license or steal ideas from Xerox PARC. But at first the earliest personal computers were homebrewed concoctions that only a hobbyist could love.

THE COMMUNITY ORGANIZERS

Among the tribes of the Bay Area in the years leading up to the birth of the personal computer was a cohort of community organizers and peace activists who learned to love computers as tools for bringing power to the people. They embraced small-scale technologies, Buckminster Fuller’s Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, and many of the tools-for-living values of the Whole Earth crowd, without being enthralled by psychedelics or repeated exposures to the Grateful Dead.

Fred Moore was an example. The son of an Army colonel stationed at the Pentagon, he had gone west to study engineering at Berkeley in 1959. Even though the U.S. military buildup in Vietnam had not begun, Moore decided to become an antiwar protestor. He camped out on the steps of Sproul Plaza, soon to become the epicenter of student demonstrations, with a sign denouncing ROTC. His protest lasted only two days (his father came to take him home), but he reenrolled at Berkeley in 1962 and resumed his rebellious ways. He served two years in jail as a draft resister and then, in 1968, moved to Palo Alto, driving down in a Volkswagen van with a baby daughter whose mother had drifted away.75

Moore planned to become an antiwar organizer there, but he discovered the computers at the Stanford Medical Center and became hooked. Since nobody ever asked him to leave, he spent his days hacking around on the computers while his daughter wandered the halls or played in the Volkswagen. He acquired a faith in the power of computers to help people take control of their lives and form communities. If they could use computers as tools for personal empowerment and learning, he believed, ordinary folks could break free of the dominance of the military-industrial establishment. “Fred was a scrawny-bearded, intense-eyed radical pacifist,” recalled Lee Felsenstein, who was part of the community organizing and computer scene in Palo Alto. “At the drop of a hat he would scurry off to pour blood on a submarine. You couldn’t really shoo him away.”76

Given his peacenik-tech passions, it is not surprising that Moore gravitated into the orbit of Stewart Brand and his Whole Earth crowd. Indeed, he ended up having a star turn at one of the weirdest events of the era: the 1971 demise party for the Whole Earth Catalog. Miraculously, the publication had ended its run with $20,000 in the bank, and Brand decided to rent the Palace of Fine Arts, an ersatz classical Greek structure in San Francisco’s Marina District, to celebrate with a thousand kindred spirits who would decide how to give away the money. He brought a stack of hundred-dollar bills, harboring a fantasy that the rock– and drug-crazed crowd would come to a judicious consensus on what to do with it. “How can we ask anyone else in the world to arrive at agreements if we can’t?” Brand asked the crowd.77

The debate lasted ten hours. Wearing a monk’s black cassock with hood, Brand let each speaker hold the stack of money while addressing the crowd, and he wrote the suggestions on a blackboard. Paul Krassner, who had been a member of Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters, gave an impassioned talk about the plight of the American Indians—“We ripped off the Indians when we came here!”—and said the money should be given to them. Brand’s wife, Lois, who happened to be an Indian, came forward to declare that she and other Indians didn’t want it. A person named Michael Kay said they should just give it out to themselves and started handing out the bills to the crowd; Brand retorted that it would be better to use it all together and asked people to pass the bills back up to him, which some of them did, prompting applause. Dozens of other suggestions, ranging from wild to wacky, were made. Flush it down the toilet! Buy more nitrous oxide for the party! Build a gigantic plastic phallic symbol to stick into the earth! At one point a member of the band Golden Toad shouted, “Focus your fucking energy! You’ve got nine million suggestions! Pick one! This could go on for the next fucking year. I came here to play music.” This led to no decision but did prompt a musical interlude featuring a belly dancer who ended by falling to the floor and writhing.

At that point Fred Moore, with his scraggly beard and wavy hair, got up and gave his occupation as “human being.” He denounced the crowd for caring about money, and to make his point he took the two dollar bills he had in his pocket and burned them. There was some debate about taking a vote, which Moore also denounced because it was a method for dividing rather than uniting people. By then it was 3 a.m., and the dazed and confused crowd had become even more so. Moore urged them to share their names so that they could stay together as a network. “A union of people here tonight is more important than letting a sum of money divide us,” he declared.78 Eventually he outlasted all but twenty or so diehards, and it was decided to give the money to him until a better idea came along.79

Since he didn’t have a bank account, Moore buried the $14,905 that was left of the $20,000 in his backyard. Eventually, after much drama and unwelcome visits from supplicants, he distributed it as loans or grants to a handful of related organizations involved in providing computer access and education in the area. The recipients were part of the techno-hippie ecosystem that emerged in Palo Alto and Menlo Park around Brand and his Whole Earth Catalog crowd.

This included the catalogue’s publisher, the Portola Institute, an alternative nonprofit that promoted “computer education for all grade levels.” Its loose-knit learning program was run by Bob Albrecht, an engineer who had dropped out of corporate America to teach computer programming to kids and Greek folk dancing to Doug Engelbart and other adults. “While living in San Francisco at the top of the crookedest street, Lombard, I frequently ran computer programming, wine tasting, and Greek dancing parties,” he recalled.80 He and his friends opened a public-access computer center, featuring a PDP-8, and he took some of his best young students on field trips, most memorably to visit Engelbart at his augmentation lab. One of the early editions of the Whole Earth Catalog featured on its end page a picture of Albrecht, sporting a porcupine brush cut, teaching some kids to use a calculator.

Albrecht, who wrote self-teaching guides, including the popular My Computer Likes Me (When I Speak BASIC), launched a publication called the People’s Computer Company, which was not really a company but called itself one in honor of Janis Joplin’s band, Big Brother and the Holding Company. The scraggly newsletter adopted as its motto “Computer power to the people.” The first issue, in October 1972, had on its cover a drawing of a boat sailing into the sunset and the hand-scrawled declaration “Computers are mostly used against people instead of for people; used to control people instead of to free them; Time to change all that—we need a PEOPLE’S COMPUTER COMPANY.”81 Most issues featured lots of line drawings of dragons—“I loved dragons ever since I was thirteen,” Albrecht recalled—and stories about computer education, BASIC programming, and various learning fairs and do-it-yourself technology festivals.82 The newsletter helped to weave together electronic hobbyists, do-it-yourselfers, and community-learning organizers.

Another embodiment of this culture was Lee Felsenstein, an earnest antiwar protestor with an electrical engineering degree from Berkeley who became a featured character in Steven Levy’s Hackers. Felsenstein was far from being a Merry Prankster. Even in the heady days of student unrest at Berkeley, he eschewed sex and drugs. He combined a political activist’s instinct for community organizing with an electronic geek’s disposition for building communications tools and networks. A faithful reader of the Whole Earth Catalog, he had an appreciation for the do-it-yourself strand in American community culture along with a faith that public access to communications tools could wrest power from governments and corporations.83

Felsenstein’s community-organizing streak and love for electronics were instilled as a child in Philadelphia, where he was born in 1945. His father was a locomotive machinist who had become a sporadically employed commercial artist, and his mother was a photographer. Both were secret members of the Communist Party. “Their outlook was that what you were fed by the media was generally phony, which was one of my father’s favorite words,” Felsenstein recalled. Even after they left the Party, his parents remained left-wing organizers. As a kid, Felsenstein picketed visiting military leaders and helped organize demonstrations in front of a Woolworth’s in support of the desegregation sit-ins in the South. “I always had a piece of paper to draw on when I was a kid, because my parents encouraged us to be creative and imaginative,” he recalled. “And on the other side there was usually some mimeographed leaflet from an old block organization event.”84

His technological interests were instilled partly by his mother, who repeatedly told of how her late father had created the small diesel engines used in trucks and trains. “I took the hint that she wanted me to be an inventor,” he said. Once, when he was reprimanded by a teacher for daydreaming, he replied, “I’m not daydreaming, I’m inventing.”85

In a household with a competitive older brother and an adopted sister, Felsenstein took refuge in going to the basement and playing with electronics. It instilled in him a sense that communications technology should enable individual empowerment: “The technology of electronics promised something I apparently wanted greatly—communication outside the hierarchical structure of the family.”86 He took a correspondence course that came with booklets and test equipment, and he bought radio handbooks and ninety-nine-cent transistors so that he could learn how to turn schematic drawings into working circuits. One of the many hackers who grew up building Heathkits and other solder-it-yourself electronic projects, he later worried that subsequent generations were growing up with sealed devices that couldn’t be explored.III “I learned electronics as a kid by messing around with old radios that were easy to tamper with because they were designed to be fixed.”87

Felsenstein’s political instincts and technological interests came together in a love for science fiction, particularly the writings of Robert Heinlein. Like generations of gamers and computer jockeys who helped to create the culture of the personal computer, he was inspired by the genre’s most common motif, that of the hacker hero who uses tech wizardry to bring down evil authority.

He went to Berkeley in 1963 to study electrical engineering, just as the revolt against the Vietnam War was brewing. Among his first acts was to join a protest, along with the poet Allen Ginsberg, against the visit of a South Vietnamese dignitary. It ran late, and he had to get a cab to make it back in time for chemistry lab.

In order to pay his tuition, he entered a work-study program that got him a job with NASA at Edwards Air Force Base, but he was forced to quit when the authorities discovered that his parents had been communists. He called his father to ask if that was true. “I don’t want to talk about it on the phone,” his father replied.88

“Keep your nose clean, son, and you won’t have any trouble getting your job back,” Felsenstein was told by an Air Force officer. But it was not in his nature to keep his nose clean. The incident had inflamed his antiauthoritarian streak. He arrived back on campus in October 1964 just as the Free Speech Movement protests erupted, and, like a sci-fi hero, he decided to use his technology skills to engage in the fray. “We were looking for nonviolent weapons, and I suddenly realized that the greatest nonviolent weapon of all was information flow.”89

At one point there was a rumor that the police had surrounded the campus, and someone shouted at Felsenstein, “Quick! Make us a police radio.” It was not something he could do on the spot, but it resulted in another lesson: “I made up my mind, I had to be out front of everyone applying tech for societal benefit.”90

His biggest insight was that creating new types of communications networks was the best way to wrest power from big institutions. That was the essence, he realized, of a free speech movement. “The Free Speech Movement was about bringing down the barriers to people-to-people communications and thus allowing the formation of connections and communities that were not handed down by powerful institutions,” he later wrote. “It laid the ground for a true revolt against the corporations and governments that were dominating our lives.”91

He began to think about what kind of information structures would facilitate this type of person-to-person communications. He first tried print, launching a newsletter for his student co-op, and then joined the underground weekly the Berkeley Barb. There he acquired the semi-ironic title of “military editor” after writing a story about a landing ship dock and using the initials “LSD” in a satirical fashion. He had hoped that “print could be the new community media,” but he became disenchanted when he “saw it turn into a centralized structure that sold spectacle.”92 At one point he developed a bullhorn with a mesh network of input wires that allowed people in the crowd to talk back. “It had no center and thus no central authority,” he said. “It was an Internet-like design, which was a way to distribute communications power to all the people.”93

He realized that the future would be shaped by the distinction between broadcast media like television, which “transmitted identical information from a central point with minimal channels for return information,” and nonbroadcast, “in which every participant is both a recipient and a generator of information.” For him, networked computers would become the tool that would allow people to take control of their lives. “They would bring the locus of power down to the people,” he later explained.94

In those pre-Internet days, before Craigslist and Facebook, there were community organizations known as Switchboards that served to make connections among people and link them to services they might be seeking. Most were low-tech, usually just a few people around a table with a couple of phones and a lot of cards and flyers tacked to the walls; they served as routers to create social networks. “It seemed that every subcommunity had one or more,” Felsenstein recalled. “I visited them to see if there was any technology they could use to forward their efforts.” At one point a friend accosted him on the street with some exciting news: one of these community groups had scored a mainframe computer by guilt-tripping some wealthy San Francisco liberals. That tip led him to a nonprofit called Resource One, which was reconfiguring the mainframe so that it could be time-shared by other Switchboards. “We had the idea that we were going to be the computer for the counterculture,” he said.95

Around that time Felsenstein put a personal ad in the Berkeley Barb that read, “Renaissance Man, Engineer and Revolutionist, seeking conversation.”96 Through it he met one of the first female hackers and cyberpunks, Jude Milhon, who wrote under the name St. Jude. She, in turn, introduced him to her companion, Efrem Lipkin, a systems programmer. The Resource One computer had not been able to find any time-sharing clients, so at Lipkin’s suggestion they embarked on a new effort, called Community Memory, to use the computer as a public electronic bulletin board. In August 1973 they set up a terminal, with a link via phone line to the mainframe, at Leopold’s Records, a student-owned music store in Berkeley.97

Felsenstein had seized on a seminal idea: public access to computer networks would allow people to form communities of interest in a do-it-yourself way. The flyer-cum-manifesto advertising the project proclaimed that “non-hierarchical channels of communication—whether by computer and modem, pen and ink, telephone, or face-to-face—are the front line of reclaiming and revitalizing our communities.”98

One smart decision Felsenstein and his friends made was to not have predefined keywords, such as help wanted or cars or babysitting, programmed into the system. Instead users could make up any keywords they wanted for their posting. This permitted the street to find its own uses for the system. The terminal became a bulletin board for posting poetry, organizing carpools, sharing restaurant ideas, and seeking compatible partners for chess, sex, studying, meditation, and just about anything else. With St. Jude leading the way, people created their own online persona and developed a literary flair not possible on cork-and-tack bulletin boards.99 Community Memory became the forerunner to Internet bulletin board systems and online services such as The WELL. “We opened the door to cyberspace and found that it was hospitable territory,” Felsenstein observed.100

Another insight, equally important for the digital age, came after a disagreement with his sometime friend Lipkin, who wanted to build a terminal that was iron-clad closed so that the people in the community couldn’t break it. Felsenstein advocated the opposite approach. If the mission was to give computing power to the people, then the hands-on imperative needed to be honored. “Efrem said if people get their hands on it they will break it,” Felsenstein recalled. “I took what became the Wikipedia philosophy, which was that allowing people to be hands-on would make them protective and fix it when broken.” He believed computers should be playthings. “If you encourage people to tamper with the equipment, you will be able to grow a computer and a community in symbiosis.”101

These instincts were crystallized into a philosophy when Felsenstein’s father, just after the terminal had been set up in Leopold’s, sent him a book called Tools for Conviviality, by Ivan Illich, an Austrian-born, American-raised philosopher and Catholic priest who criticized the domineering role of technocratic elites. Part of Illich’s remedy was to create technology that would be intuitive, easy to learn, and “convivial.” The goal, he wrote, should be to “give people tools that guarantee their right to work with high, independent efficiency.”102 Like Engelbart and Licklider, Illich spoke of the need for a “symbiosis” between the user and the tool.

Felsenstein embraced Illich’s notion that computers should be built in a way that encouraged hands-on tinkering. “His writings encouraged me to be the pied piper leading people to equipment they could use.” A dozen years later, when they finally met, Illich asked him, “If you want to connect people, why do you wish to interpose computers between them?” Felsenstein replied, “I want computers to be the tools that connect people and to be in harmony with them.”103

Felsenstein wove together, in a very American way, the ideals of the maker culture—the fun and fulfillment that comes from an informal, peer-led, do-it-ourselves learning experience—with the hacker culture’s enthusiasm for technological tools and the New Left’s instinct for community organizing.IV As he told a room full of earnest hobbyists at the Bay Area Maker Faire of 2013, after noting the odd but apt phenomenon of having a 1960s revolutionary as their keynote speaker, “The roots of the personal computer can be found in the Free Speech Movement that arose at Berkeley in 1964 and in the Whole Earth Catalog, which did the marketing for the do-it-yourself ideals behind the personal computer movement.”104

In the fall of 1974, Felsenstein put together specifications for a “Tom Swift Terminal,” which was, he said, “a Convivial Cybernetic Device” named after “the American folk hero most likely to be found tampering with the equipment.”105 It was a sturdy terminal designed to connect people to a mainframe computer or network. Felsenstein never got it fully deployed, but he mimeographed copies of the specs and handed them out to those who might embrace the notion. It helped nudge the Community Memory and Whole Earth Catalog crowd toward his creed that computers should be personal and convivial. That way they could become tools for ordinary people, not just the technological elite. In the poet Richard Brautigan’s phrase, they should be “machines of loving grace,” so Felsenstein named the consulting firm he formed Loving Grace Cybernetics.

Felsenstein was a natural-born organizer, so he decided to create a community of people who shared his philosophy. “My proposition, following Illich, was that a computer could only survive if it grew a computer club around itself,” he explained. Along with Fred Moore and Bob Albrecht, he had become a regular at a potluck dinner hosted on Wednesday nights at the People’s Computer Center. Another regular was Gordon French, a lanky engineer who loved to build his own computers. Among the topics they discussed was “What will personal computers really be like once they finally come into existence?” When the potluck dinners petered out early in 1975, Moore and French and Felsenstein decided to start a new club. Their first flyer proclaimed, “Are you building your own computer? Terminal? TV typewriter? I/O device? Or some other digital black-magic box? If so, you might like to come to a gathering of people with likeminded interests.”106

The Homebrew Computer Club, as they dubbed it, ended up attracting a cross-section of enthusiasts from the many cultural tribes of the Bay Area digital world. “It had its psychedelic rangers (not many), its ham radio rule-followers, its white-shoe would-be industry potentates, its misfit second– and third-string techs and engineers, and its other offbeat folks—including a prim and proper lady who sat up front who had been, I was later told, President Eisenhower’s personal pilot when she was a male,” Felsenstein recalled. “They all wanted there to be personal computers, and they all wanted to throw off the constraints of institutions, be they government, IBM or their employers. People just wanted to get digital grit under their fingernails and play in the process.”107

This first meeting of the Homebrew Computer Club was held on a rainy Wednesday, March 5, 1975, in Gordon French’s Menlo Park garage. It occurred just when the first truly personal home computer became available, not from Silicon Valley but from a sagebrush-strewn strip mall in a silicon desert.

ED ROBERTS AND THE ALTAIR

There was one other character type that helped to create the personal computer: the serial entrepreneur. Eventually these overcaffeinated startup jockeys would come to dominate Silicon Valley, edging aside the hippies, Whole Earthers, community organizers, and hackers. But the first of this breed to be successful in creating a marketable personal computer was based far away from both Silicon Valley and the computer centers of the East Coast.

When the Intel 8080 microprocessor was about to come out in April 1974, Ed Roberts was able to score some handwritten data sheets describing it. A burly entrepreneur with an office in an Albuquerque, New Mexico, storefront, he came up with a perfectly simple idea of what he could make using this “computer on a chip”: a computer.108

Roberts was not a computer scientist or even a hacker. He had no grand theories about augmenting intelligence or the symbiosis wrought by graphical user interfaces. He had never heard of Vannevar Bush or Doug Engelbart. He was instead a hobbyist. Indeed, he had a curiosity and passion that made him, in the words of one coworker, “the world’s ultimate hobbyist.”109 Not the type who got all gooey talking about the maker culture but the type who catered to (and acted like an overgrown version of) the pimply-faced boys who loved to fly model airplanes and shoot off rockets in the backyard. Roberts helped usher in a period in which the world of personal computing was pushed forward not by whiz kids from Stanford and MIT but by Heathkit hobbyists who loved the sweet smell of smoldering solder.

Roberts was born in Miami in 1941, the son of a household appliance repairman. He joined the Air Force, which sent him to Oklahoma State to get an engineering degree and then assigned him to the laser division of a weapons lab in Albuquerque. There he began starting businesses, such as one that ran the animated characters in the Christmas display of a department store. In 1969 he and an Air Force mate named Forrest Mims launched a company aimed at the small but passionate market of model rocket enthusiasts. It produced do-it-yourself kits that allowed backyard space cadets to make miniature flashing lights and radio gadgets so that they could track their toy rockets.

Roberts had the buoyancy of a startup junkie. According to Mims, “He was utterly confident his entrepreneurial gifts would allow him to fulfill his ambitions of earning a million dollars, learning to fly, owning his own airplane, living on a farm, and completing medical school.”110 They named their company MITS, in order to evoke MIT, and then reverse-engineered it as an acronym for Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems. Its $100-a-month office space, which had formerly been a snack bar, was wedged between a massage parlor and a Laundromat in a fraying strip mall. The old sign reading “The Enchanted Sandwich Shop” still, rather aptly, hung over the MITS door.

Following in the footsteps of Jack Kilby of Texas Instruments, Roberts next forayed into the electronic calculator business. Understanding the hobbyist mentality, he sold his calculators as unassembled do-it-yourself kits, even though assembled devices would not have cost much more. By then he’d had the good fortune of meeting Les Solomon, the technical editor of Popular Electronics, who had visited Albuquerque on a story-scouting tour. Solomon commissioned Roberts to write a piece, whose headline, “Electronic Desk Calculator You Can Build,” appeared on the November 1971 cover. By 1973 MITS had 110 employees and $1 million in sales. But pocket calculator prices were collapsing, and there was no profit left to be made. “We went through a period where our cost to ship a calculator kit was $39, and you could buy one in a drugstore for $29,” Roberts recalled.111 By the end of 1974 MITS was more than $350,000 in debt.

Being a brash entrepreneur, Roberts responded to the crisis by deciding to launch a whole new business. He had always been fascinated by computers, and he assumed that other hobbyists felt the same. His goal, he enthused to a friend, was building a computer for the masses that would eliminate the Computer Priesthood once and for all. After studying the instruction set for the Intel 8080, Roberts concluded that MITS could make a do-it-yourself kit for a rudimentary computer that would be so cheap, under $400, that every enthusiast would buy it. “We thought he was off the deep end,” a colleague later confessed.112