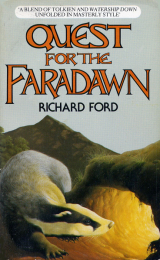

Текст книги "Quest for the Faradawn"

Автор книги: Richard Ford

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

CHAPTER VIII

The fresh green days of spring passed all too quickly and turned into a hot, hazy, dry summer. Nab spent the long hours of sunshine drowsing in the shade under the tall bracken that covered all the top part of the wood or lying at the foot of one of the great beech trees where the ground always seemed cool and there was plenty of refreshing sorrel and chickweed to nibble at. As evening fell he would make his way slowly back home and then with Brock or Perryfoot or sometimes Rufus the Red he would go searching for food.

The incident by the stream had dominated everyone’s thoughts all summer. At first it had been thought by the elders of the Council that it would be unwise to tell the wood of what had happened for fear of causing panic and even anger at Nab; but it had not been long before rumours had begun to spread and, as most of these wild and exaggerated tales were different, it had eventually been considered the best policy to call a Council Meeting and clear everything up by disclosing the truth. It had been a somewhat unruly meeting with Wythen having to use all his authority to control matters, but Nab, at his first Council and feeling extremely nervous, had given a good account of himself in his attempts to explain exactly what he had done and why he had done it. This, coupled with the fact that most of the woodland animals now knew him and liked him, eventually won the day and it was decided that the only danger was the possibility that the little girl would have told her parents and the Urkku would come searching for him. Thus the guardians of the wood, Warrigal and Brock, were asked to keep an especially careful look-out, but since it was now almost the end of summer and there had been no Urkku in the wood since the affair, it was believed, to everyone’s relief, that the little girl had kept the meeting secret.

The incident had had a particularly marked effect on Nab. Although he had been aware before that he was a different type of animal from any of the others in the wood, it had never before seemed to matter very much. Now he had seen other Urkku he was filled with a curiosity to find out more about them for himself. He thought constantly of the little girl and was unable to clear his mind of his golden image of her as she had stood waving at him and smiling from the banks of the stream with the breeze ruffling her dress and blowing in her hair. But his memory was always bittersweet as he recalled the confused turmoil of emotions that had made him snatch away his hand and run off. He also began to realize, for the first time, that he had not been born in the wood and that he must have two parents somewhere of his own race. Why had they left him under the Great Oak so many seasons ago?

Where did they come from? What were they like? These questions repeated themselves over and over in his mind and he spent much time thinking about them while he was walking through the wood in the evening or musing in the daytime under the bracken. One night Tara had gone into his bush for a talk and found him sitting in a corner looking completely lost in himself. She turned round and without being noticed made her way back to the sett. There she began to dig in the wall where, so many seasons ago, she had buried the multi-coloured shawl in which he had been found. The walls of the sett were rubbed smooth and hard but her strong claws soon felt the cavity in which she had placed it. Taking it out carefully she shook it to get any soil off and then, having repaired the wall, went back up the passage and once more into Nab’s bush. She went up to him and rubbed her nose against his neck. He looked up slowly and stared into her warm black eyes; ‘Hello, it’s nice to see you,’ he said.

‘Nab, I’ve brought you something. It’s for you, to keep.’ She produced the large gaily coloured shawl and handed it to him. He took it and, standing up, held it so that it hung straight and the pattern of the colours could be clearly seen. His eyes widened in amazement the more he looked and he began to feel it, running his fingers up and down the soft silk and through the long fringes that hung down all around it.

‘It’s for me,’ he said, ‘to keep? I’ve never seen anything like it before. Where did you find it?’

‘It’s for you because it belongs to you. When you were left in the wood you were wrapped in many layers of cloth because, as Brock has told you, it was a cold night and the snow was heavy on the ground. When Brock carried you back to me I took the outer layers of cloth off until I found, next to your skin, this shawl, and I buried it in one of the walls of the sett, ready to give to you when the time was right. So you see, it was given to you by your mother and father; it belonged to them and they gave it to you. It is a link with your parents.’

Nab sat down clutching the shawl tightly against him and he began to cry softly to himself. Tara went up to him and put her paw on his shoulder.

‘What were they like?’ he asked. ‘Brock saw them, didn’t he?’

‘They were good Urkku. Brock felt no sense of danger or fear when he was near them.’ She described the events of the first night as Brock had told them to her. At this moment he was out with Warrigal walking round the boundaries of the wood; it was a pity he wasn’t here now to tell Nab at first hand but the boy could talk to him later.

When she had finished, Nab put his arm around her shoulder and buried his face against her neck. He stayed like that for a long time and when eventually he raised his head he smiled and there was a sparkle in his eye. He removed the layers of bark which formed his clothing and, before replacing them, tied the coloured shawl around his waist.

Summer in Silver Wood seemed to last for ever. The days became too hot for the animals to do anything except lie in the shade around the edge of the wood where there was a breeze. In the centre of the wood there wasn’t a breath of wind to relieve the intensity of the heat and the stillness hung so heavily one could almost touch it. The only sound was the constant buzzing of the insects as they hovered and darted over the tall canopy of green bracken that filled the wood. Sometimes, as Nab lay under it staring up at the sky, he would see the topmost branches of the tallest silver birch trees waving gently in a breeze that only existed in heaven and he would stare at the movement of the leaves until he fell asleep. Occasionally something would startle a blackbird and it would chatter loudly as it flew off to settle on another branch. Nab would then wake up and decide to go for a little stroll; it was impossible to walk through the bracken so he would crawl on all fours beneath it until he found another spot where he felt secure and there he would again fall asleep. Under the ceiling formed by the interlaced bracken leaves there was a different world, a cool subterranean jungle where the green stems of the bracken were like trees and the floor was of rich dark brown peat under a light brown carpet made up of the sharp and spiky remains of last year’s dead bracken. As Nab made his way through this jungle he would find his hands and knees criss-crossed with their imprint and he had to be careful not to let them cause splinters. He would see spiders scurrying about their business and metallic green beetles walking slowly along the bracken branches. As he moved he could feel the bracken dust which he had disturbed catch in his throat and he could smell and touch the damp peat, still moist under its covering of dead bracken. Sometimes he would come across a cluster of wood sorrel with their delicate white flowers and would pick a leaf and chew it to refresh himself.

Eventually Nab began to notice the first harbingers of autumn; although the sun still shone and it was hot during the day, the evenings grew damp and chill where before they had been balmy, and now there was a dew on the ground. By the stream, meadowsweet appeared with its tall stalks and clustered heads of creamy white flowers which scattered as they were knocked, and in the wood the autumn toadstools made their way out of the mat of damp decaying leaves on the floor; the blusher with its scarlet cap covered in little rough skin-like flakes and the great orange boletus which felt shiny and shone in the dew but whose flesh, when the spongy gills had been removed, was one of the treats of autumn. In the mornings and evenings the hollows filled with mist which disappeared as the sun fought its way through to light up the golden leaves; Nab would lie on his back in the warmth of the midday sun under the great beech and watch the leaves gently floating down; if they appeared to be drifting near he enjoyed trying to guess whether or not they would land on him, and he was always surprised at how few, out of the hundreds that fell, succeeded.

The animals feared autumn; not because of its natural sadness or because it heralded the beginning of winter but because it was the season in which, after a period of delicious peace during the summer, the Urkku amply compensated for the rest with a time of killing and slaughter which was the most terrible of the year. Nab was now allowed to watch the Urkku from the shelter of his bush, although Brock was always with him to make sure he did nothing foolish. Although Nab had been told, when he had seen animals that had been shot, that their death was the doing of the Urkku he had become confused this summer because he could not reconcile the image he had built up of them as a race of savage killers with the reality of the two he had actually seen. However, as he watched with mounting horror and shame the activities of members of his own race as they spread terror and pain throughout the wood, his confusion gave way to a seething anger. With every crack of a shot which echoed through the wood his whole body ached as he imagined the pain that was being inflicted, and Brock was always having to restrain him from rushing out of the bush to attack the Urkku.

That autumn the killing seemed to be particularly bad; more Urkku seemed to Come and they came more often. The wood seemed to be constantly full of the lingering smells of gunpowder and cigarette smoke and wherever Nab went he found reminders of them. The undergrowth was crushed, branches were broken, toadstools had been kicked over and tufts of bloody fur and feathers lay amongst the withering brown leaves. The wood seemed defiled and, unable to escape the oppressive weight of their almost constant presence, Nab’s moods wavered from a brooding silent depression to a seething rage.

The animals crept furtively through the bushes, moving quickly and quietly so that the whole wood seemed to have died. The rabbits, led by Pictor, had suffered particularly severely this autumn as the result of a new method of killing which meant that they were now no longer safe even at night. Nab had been out in the wood the first time it was used and watched it in operation. He had been crouching down behind the old rotten stump of a silver birch picking a toadstool and examining it for worms when he had suddenly become aware of the most terrible noise, grinding and clanking, coming from the direction of the pond. Looking up he had seen an enormous Urkku machine lumbering and lurching its way ponderously over the field towards the wood. The clouds were covering the moon that night and it was dark but Nab could make out the shape of the machine; it seemed like an ordinary tractor with a large trailer behind such as he had seen in the fields on hundreds of previous occasions, but somehow, at night, it seemed terrifying, like an enormous beast. When it arrived in the middle of the field at the front of the wood it shuddered to a halt and suddenly Nab was blinded by a bright shaft of light that shone straight in his eyes; he could see nothing and do nothing; he shook his head and screwed up his eyes in panic but when he opened them again he found that the light had gone from directly in front of his eyes and was moving away to his left in a great white beam that came from the trailer and searched across the field. As the light moved on, it found three rabbits who had been eating just to the front of the wood; they stopped exactly as they were when the light had caught them, paralysed with fear and unable to see just as he had been. Two shots split through the night and two of the three toppled over onto their sides, their legs kicking in the air. The third one was galvanized into action by the shots and began to scurry away but, instead of turning to its side and so getting out of the light, it ran down the path of light which shone from the trailer. Nab heard the guttural sounds of an Urkku as it whooped with delight at the prospect of some sport and the machine started to clank and grind on in pursuit of the rabbit, which was now hopping pathetically from side to side in its prison of light. The laughter and shouts of the Urkku as they tried to make it run faster filled Nab’s ears and head and his stomach felt sick. He watched as the rabbit eventually became so tired and confused that it stopped and, turning round, ran back up the shaft of light towards the tractor in a last panicking attempt to escape from its torment. Nab’s ears rang from the shot and the rabbit looked as if it had run into an invisible wall as it was suddenly flung over into a backward somersault and landed kicking on the grass. The boy watched as the tractor stopped and two Urkku jumped down and ran to pick up the dead rabbits. They threw them into the back of the trailer and then the machine went back the way it had come to disappear finally as it went behind the hill at the back of the pond.

The mellow autumn golds eventually turned into the cold grey shades of winter and the winds came to blow off the few remaining leaves from the trees; only the oak leaves clung stubbornly to their branches, the last to come and the last to leave. Nab was out with Rufus in the late afternoon not many moons after the incident with the rabbits. The fox had been showing Nab the spot where he’d seen some chickweed growing at the back of the wood by the little stream and the boy had gathered a handful to take back for his meal with a few hazel nuts from his store. The fox’s head bobbed up and down beside him as they made their way back to the front of the wood.

‘You’ll be able to pick at that chickweed all winter; I’ve never seen it there before,’ said Rufus.

‘Yes. I had to go down to the big stream before. It will be a big help,’ the boy replied. He didn’t often go out with the fox who always foraged for food on his own, but Rufus often came to the rhododendron bush to tell the boy about places which none of the other animals had been to or else to recount legends of the Fox from the time Before-Man, when foxes lived, not as they did now in isolated individual holes but in a vast underground colony which stretched as far as the mind could think about and were ruled by the Winnat – three foxes whose bodies were covered in beaten copper wrought for them by the Elvensmiths in return for an alliance with the Elflords.

They walked in silence for a while until suddenly Nab felt a sharp tap on his leg as the fox knocked him with the side of his head. As he stopped Rufus motioned to him to get down. The boy dropped quietly to the ground and followed on all fours as Rufus silently led the way to some cover behind the base of an oak.

‘Look,’ whispered the fox.

Nab looked out over the bleak winter fields but could see nothing at first. Then he saw, just coming into sight on his left, two Urkku walking along the front of the wood, both with their guns tucked under their arms. They were talking very quietly and looking intently all around. Nab looked at the fox, who motioned him to lie down flat; he himself was crouched as if to spring, with his whole body quivering, his sharp ears erect and the black tip of his nose twisted to one side as it strained to pick up every scent on the air. The Urkku stopped and looked around them; for one long agonizing spell they seemed to be staring straight at the oak tree and then their gaze moved on. Suddenly, to Nab’s horror, he saw one of them motion with his head to the other in the direction of the part of the wood where he and Rufus were. They took the guns from under their arms and held them with one hand under the barrel and the other by the trigger, ready to raise to their shoulders and shoot, then they began to advance slowly in to the wood. Nab looked at the fox in panic.

‘Listen,’ said Rufus. ‘They don’t know we’re here but if they carry on as they are doing they are bound to find us. If they come too close I’ll run off towards the front of the wood so that they can see me. That should take their attention away. You must stay here and not move until you feel it’s safe. Then go straight for your bush and stay there. Above all, stay where you are until they’ve gone; I’ll try and get them to follow me.’

‘But what about you?’ Nab whispered.

‘I'll be all right. They rarely manage to kill us with their death sticks. We’re too quick for them. Now, keep quiet.’

They lay side by side on the earth behind the oak. Nab could feel the damp coming through his layers of bark and his knees were sore. As the Urkku came closer and he became more frightened, his hands reached out to feel the rough bark of the oak and he gained comfort from the power and strength of the tree. He looked at Rufus. The fox’s eyes were staring at the Urkku with a black intensity and his quivering body seemed about to explode with energy. They were now barely twenty paces away and Nab’s heart was pounding so strongly that he felt certain they must have heard his frightened rasps of breath. Rufus looked at him and put his paw on the boy’s arm; then he burst out from behind the tree and glided noiselessly away through the tufts of grass and around the fallen logs that littered the floor, his great bushy tail flowing away behind him.

Nab watched as one of the Urkku caught sight of a flash of brown and shouted to the other, pointing excitedly at the undergrowth. They both raised their guns and the boy’s heart stopped as two shots echoed through the wood; desperately he looked for the fox and then to his relief he saw him by the stile at the edge of the field running across to the other side of the wood where the trees were thicker and he would be safe. Then he heard another guttural shout and two more shots shattered the air. Rufus crumpled up and toppled over on his side; in a blind fit of grief the boy ran out from behind the oak tree and dashed across the wood until he fell on his knees beside his friend. His whole body was seized with uncontrollable spasms as he sobbed hysterically. ‘Rufus,’ he cried, and cradled his arms under the fox’s head to bury his face against the warm fur. The eyes slowly opened; a few short heartbeats ago they had shone with life and energy; now they were liquid brown and still and they looked at the boy with sadness and love and hope. The boy felt his hand warm and sticky where it held the fox and then the eyes closed and the head sagged. Nab knew he was dead and a surge of sickness welled into his stomach as the full horror of what had happened suddenly hit him. Through a blurred veil of tears he looked at the black nose and the mouth which was drawn back in death so that the teeth could be seen; he looked at the two triangular ears and he buried his hand in the deep fur around his neck. He was unable to accept that life had gone when the body was here exactly as it had been when they were both behind the oak. The eyes would never again look at him; he would never again see the fox’s head as it poked its way through the rhododendron bush and there would be no more stories on winter evenings. He kept going over these things in his mind to try to make himself understand but he could not grasp it; it was too much to comprehend. Still shaking violently as the tears flowed down his face he threw himself over the dead body of the fox.

‘Look, Jeff; I told you. It’s a kid.’

Nab heard the Urkku behind him and felt pressure on his shoulder as a hand gripped him and tried to raise burn up from Rufus’s body. He had forgotten the fox’s last words to him, that he was not to move until it was safe, and he realized with a shock of remorse that Rufus had been killed trying to protect him but now, through his own fault, it had been in vain.

The boy tried to jump up but found that he couldn’t; the Urkku had too firm a hold of him.

‘Steady, kid. Who are you? Chris, look at it! It’s dressed in bark; and look at its hair. I don’t think it can speak. What’s your name, kid? See if the fox is dead, Chris.’

Nab watched in horror as the other Urkku put his boot under Rufus’s body and kicked it over; the head pointed straight up for a second or two and then toppled over the other way. Then the Urkku pulled out a knife and hacked at the tail; when it had come off he kicked the fox over so that it landed nose down in the ditch, its once magnificent body spreadeagled and twisted crazily so that its back legs faced one way and its front legs the other. Suddenly all the sadness and grief that Nab felt turned into a searing anger and hatred and he tore free of the Urkku’s hand and flew at him, biting and scratching at the man’s face. The force and energy with which the boy charged were enough to knock him over and they rolled on to a tussock of grass as the gun went flying. Nab felt his nails sink into the man’s cheek and as he drew his hand down he felt blood.

‘Get him off! For God’s sake get him off.’

The other Urkku grabbed the boy tightly around the waist and pulled him away; he struggled ferociously but the Urkku was too strong and he was unable to break free. The man on the ground slowly got up, cupping a hand over his cheek where three large gashes oozed blood.

‘Come here, you little brat. I’ll teach you,’ and, while the other held Nab, he struck him across the face repeatedly with the back of his hand.

‘Take it easy Jeff; it’s only a kid.’

‘I don’t care – look at my face.’

‘You’ll be all right, it’s only a scratch. Well, we can’t leave him here. Best take him back home where Ma can decide what to do.’

Nab redoubled his efforts to get free as he realized with sudden panic that the Urkku intended to take him away from the wood. His mind swirled as hundreds of thoughts raced through it; images of the Urkku homes he had built up from conversations with Bibbington and Cawdor and Rufus; plans of escape; dreadful worries about where he would sleep tonight and what the Urkku were going to do with him; thoughts of Brock and Warrigal and Perryfoot and Tara coupled with terrible fears that he might never see them again. Then through all his panic would flash, clear and still, a picture of Rufus as he lay on the damp bracken dying, and the tears once again began to flood from him.

He felt himself being half dragged, half carried through the wood towards the stile and he was pulled roughly over it into the field. He was still struggling and biting and scratching but the numbness in his face and jaw and his desperate fight with the Urkku had taken their toll of his body and he could no longer muster the energy to do more than wave his arms around in a pathetic token gesture of aggression. He saw Silver Wood recede as he was taken across the field; the winter evening was now drawing in and the wood looked black, deep and impenetrable. Nab was somehow amazed that through all the terrible events of that afternoon it had remained exactly the same, nothing had changed; his rhododendron bush was still there and so were all the great trees. It had simply watched impassively as the horrors had unfolded before it and he felt vaguely resentful at its inability to help him.

They passed the pond as great black clouds began to appear in the grey sky bringing little spots of rain in the wind which stung his face and mingled comfortingly with his tears, as if all Nature were crying with him. As they reached the rise at the top of the little hill past the pond the Urkku stopped for a rest. Nab looked back at the wood standing aloof in the distance. It was his home, he had never slept anywhere else and now he was being taken away, perhaps never to see it again. His heart was heavy and his stomach felt as if a thousand butterflies were fluttering inside him; suddenly he felt the arms round his stomach tighten and he was pulled off again down the far side of the slope. Desperately he tried to fix a picture of the wood m his mind and his eyes clung to the treetops as they got smaller, until eventuallу they disappeared out of sight behind the top of the hill.