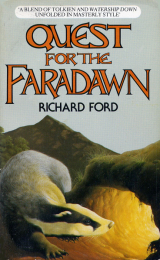

Текст книги "Quest for the Faradawn"

Автор книги: Richard Ford

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

Wythen let the hubbub continue for some time as he knew it would be useless to try and stop it, for it gave them all a chance to express their opinions before the discussion went any further. When the noise began to subside, he called out for silence and eventually the last mutterings died away. Brock was not so afraid as he felt he ought to be; in fact he felt strangely confident, although this may have been partly due to the fact that he was almost certain Wythen was on his side.

‘I shall now ask Warrigal to give you his opinions and views on the matter before us,’ said the owl, ‘and you may then ask questions. Before we go on, however, I would first like to ask Sam to tell us whether there has been any talk of this in the village.’ Sam stood up again and said that no, there had been no mention of it at all and it was the first he had heard of it.

Warrigal then flew down and stood in the centre of the open space. As he talked he turned round and round slowly so as to address every part of the meeting in turn, and he opened his wings when he wished to gesticulate or emphasize a particular point. His speech was masterful; it was full of references to legend and the time Before-Man and he sprinkled it with many veiled allusions to the Magical Peoples and the Elflord. He recited the legend of the Urkku Saviour with its ending which had been lost with the passage of time and which no one, save perhaps the Elflord himself, knew. Warrigal knew that the animals loved legends and stories and that the thought that they might actually be about to observe a legend at first hand would be enough to at least partly persuade them to allow the Urkku to stay in the wood. Coupled with this, the fear and respect with which all animals treated the name of the Elflord and the implication that he both knew of the Urkku and wished it to remain, should convince the Council and the other animals that it was right for the Urkku to stay.

When he had finished, he remained where he was and Wythen thanked him (feeling secretly very proud of his son for this extremely clever speech) and asked if there were any questions. At first there was only an embarrassed silence as every animal tried to pluck up courage to move forward and speak what was on his mind. Eventually Rufus broke it with a slightly nervous cough; he thought to himself that he would rather face six hounds than speak in public like this.

‘I, ’ he started, and gave another cough to clear his throat, ‘I think I speak for most of us when I say that none of us likes the idea of having an Urkku in the wood.’ Little murmurs of approval greeted this statement and gave him courage to carry on. His voice grew bolder and louder. ‘The Urkku have never done anything but harm to us; they destroy our homes, they poison our food and they try and kill us by any one of a hundred ways, all of which are liable to cause us the most horrible pain and suffering. Why then should we help any Urkku, even if it is only a young one?’ He stopped for he could think of no more to say: the thought of the Urkku made him angry and when he was angry he found it hard to think clearly; a fox must always remain cool and unflustered.

Pictor then voiced another point which was on all their minds. ‘How can we trust him?’ he said. ‘While he’s a baby I agree he can do us no harm but as he grows he will learn all our secrets and our defences and, worse still, he will find out where our homes are. What if then he joins the Urkku; he could destroy us all in a single day with what he knows. I don’t like it.’

Then Sterndale spoke. ‘I agree with everything Rufus and Pictor have said but I feel that we must put our trust and our faith in the opinions of our two “elder statesmen” Wythen and Bruin. In any case the Urkku can do no harm for a number of seasons yet, and if things turn out for the worse we shall have to kill him before he goes over to the Urkku. But I, for one, would like to wait and see for a while: if the legends are true then we would be foolish to get rid of him now.’

The rest of the Council agreed that the decision should be left with Wythen and Bruin. Bruin spoke first and said that, like his noble friend Sterndale, he thought that ‘wait and see’ was the best policy, although secretly he believed that the little baby in the sett would prove in some way, although he didn’t know how, to be the friend and ally of which legend had spoken ever since he could remember.

Wythen, of course, agreed. When Warrigal had told him the news he had known immediately that the time had come of which he had dreamt for so long. The baby should stay with Brock, he told the meeting, because it was obviously safe and happy there and they could all trust Bruin’s grandson whom they knew to be a brave and imaginative badger with a practical partner who would look after and guard the baby in the best possible way. The baby’s progress would be reported to the Council at the seasonal meetings and decisions as to his future would be taken then.

With that he wished them all good luck for tomorrow and, as the moon began to sink in the night sky, all the animals of the wood made their way thoughtfully back to their various holes and setts and roosts, where they pondered over the strange story they had heard.

Mystery was in the air and there was not one of them who, beneath his overriding fear of the Killing tomorrow, did not feel a little thrill of anticipation as he settled down for what remained of the night.

CHAPTER V

The next day dawned bright and clear and cold; the sun shone down from a blue sky, cloudless except for a few wisps of white that drifted purposefully across. Already drips of thawing snow could be heard all over the wood and the icy crust that had formed on the surface began to give way to a mushy layer of large wet crystals which sank as they were trodden on.

Brock was suddenly woken by the persistent hooting of an owl. He looked across at Tara and the baby; she had been fast asleep when he came in from the meeting last night and he had not told her the good news that the Council had agreed that they could keep the Urkku in the wood – at least until he began to grow into an adult. She was awake now and, when he told her, she was both pleased and relieved. ‘It’s odd,’ she said softly so as not to waken the baby, ‘in only one day and night I’ve grown really fond of him and I think he trusts me and feels comfortable with me. I was dreadfully worried that the Council might take him away.’

‘Listen,’ said Brock, ‘do you hear it; Warrigal’s warning? He’s by the pond; we arranged that he would roost there and hoot loudly when he saw the Urkku coming. You must stay down here of course when they’re in the wood and keep the baby quiet. Although there’s very little chance of their hearing him crying from above we must not take the risk.’

‘Where are you going?’ asked Tara.

‘I’m going up to the surface to see what happens. Don’t worry; I’ll stay in the passage and just poke my nose out as far as I need to be able to watch. I’m anxious to see what comes of the plans the Council arranged last night. Besides, Bruin is too old to be up during the day now – he needs his sleep – and he asked me to report to him.’

When Brock reached the top he cautiously put the black tip of his nose out and looked to left and right before proceeding, a pace at a time, until he could see almost the whole of the field at the front. All around him, in the wood, hundreds of rabbits were running in from their morning feed and vanishing into their holes. He could see Pictor in the field shouting at them to get a move on, hopping after them and herding them in like a sheepdog until he himself finally vanished down his hole in the centre of the rhododendron bush to the left of the Great Beech. He could also make out in the distance a number of hares running off over the fields, although he couldn’t tell whether Perryfoot was among them. If only they could keep their ears down when they ran, Brock thought, they would be so much more difficult to spot. Still they were far enough away from the Urkku not to be fired at and there were no mishaps.

He could see the Urkku approaching over the field. It was a frightening sight. There seemed to be very many of them and they were stretched in a single straight line right across the field. Slowly they walked towards Silver Wood with their death sticks pointing outwards and downwards from their bodies. There was a hum of conversation from the line which broke the stillness of the morning and shattered the peace. Brock could smell the unmistakable pungent smell of Urkku and the other smell which often came from them: a cloying smoky smell which rasped in his nose and stuck in his throat so that he found it hard to breathe. These smells lingered in the wood where the Urkku had been, sometimes for a whole day and night, tainting the air and serving as an awful reminder of the death and suffering they had caused, for it was extremely rare that Urkku came into Silver Wood except to kill.

When the line got to the very edge of the wood it stopped and an Urkku at one end gave a great shout; suddenly the air was full of a cacophony of strange whistles, shouts, guttural calls and the sound of the undergrowth being thrashed. This noise came from behind Brock, at the back of the wood, and slowly began to come nearer. These were the beaters.

Brock waited, his heart pounding. He could see very close to him one of the Urkku standing with his legs apart and the death stick raised against his shoulder ready to kill anything that flew out; his body was round and fat so that Brock could see, where the overjacket was open, a great roll of flesh hanging over the belt in the middle of the man’s stomach; the face was a purply-red colour and had loose jowls of skin hanging down around the neck.

Sterndale had gathered his pheasants together in the innermost part of the wood where the rhododendrons and undergrowth were so thick that the beaters were unable to get through. They had been there since before dawn and he had been talking to them in his low murmuring cackle, telling them to stay on the ground, keep their heads down and their tails low and above all not to move, no matter how close the beaters came. If they stayed where they were then they would be safe, but if they lost their nerve and flew up they would be as good as dead. Some of the pheasants were last year’s brood and there were a number of veterans of two or even three seasons; these experienced ones knew the routine and were fairly easy to handle. It was the current year’s brood that were always difficult; they had been bom and reared by the Urkku and kept in cages until they were old enough; then they had been let out into the fields and woods around the Urkku dwelling and fed with com twice a day by hand. They had therefore got used to trusting the Urkku and expecting only food and protection from them; they were far more likely to go towards the beaters than away from them and were totally unable to comprehend the fact that if they flew up and were seen they would be shot at and injured or killed. Sterndale had had to have many long and frightening talks with them but it was really only when one of the arrogant young cocks who had consistently accused Sterndale of being old-fashioned and out of touch had come limping back one day with half his chest blown away by the very same Urkku who had some short time previously been throwing down com for him, that they had begun to comprehend. The difficulty was that Sterndale couldn’t explain, because he himself couldn’t understand, why the Urkku went to such enormous trouble to protect them from poison or shooting by any of their natural enemies and then later, when they were fully grown, would organize themselves into groups and purposely try to slaughter as many as they could. In one of his talks with Wythen, the owl had told him that the Urkku were a race of creatures which enjoyed killing and that they protected the pheasants only so that they themselves could have the pleasure of killing them later on, but for a long time Sterndale had been unable to believe that.

The beaters were now coming closer. The cacophony of hoots, whistles and shouts drew slowly nearer and the thrashing of the undergrowth sounded deafening. This was the most difficult part; trying to keep his flock from panicking. He could see some of them now shifting about nervously from foot to foot and in their eyes he recognized the unmistakable glazed look of fear.

‘Don’t move, ’ he cackled as loud as he dared, but his command was lost in the din as the Urkku came nearer until the noise seemed to blot out everything and the undergrowth all around seemed to come alive. Sterndale felt his heart pounding and the blood rushing in his ears as he closed his eyes and with an enormous effort forced himself to blot out the sound and concentrate on rooting his feet to the ground and conquering all the natural instincts which urged him to fly away.

The worst happened. One of the younger cocks, thinking that he saw a chance to defy Sterndale’s leadership and prove himself, took off straight ahead towards the guns. The young hens, who were already terrified, suddenly panicked and, seeing their cock flying off, followed him. Only Sterndale and the other veterans and three or four of the less flighty new hens kept their nerve and stayed where they were. The old pheasant, feeling sick to his stomach, waited an agonizing few seconds and then suddenly the wood erupted into a hideous bedlam of explosions as the Urkku blasted away and the birds plummeted to earth, to land with a series of sickening thuds on the snow. The air was full of the squawks and cries of pain and fear as the injured birds struggled desperately to get away into the undergrowth, leaving vivid trails of crimson over the snow. The cracks of the guns had stopped now and the Urkku were shouting and laughing with joy at the size of their kill. Sterndale and the others, crouching fearfully in the rhododendrons, could hear the loud crashing of the dogs as they ran after the injured or collected the dead to take them back to their masters. Suddenly Sterndale saw a great golden shape bound past a few paces away with a grim look on his face. He stopped and turned and ran back the way he had come. ‘Sam, ’ croaked Sterndale, as quietly as he could, and the dog halted, looked round and then, spotting the pheasant, walked quietly towards him. ‘A slaughter,' growled the dog, ‘a massacre. What went wrong?’

‘Inexperience and panic, Sam, but you had better go back or your human will be leaving you without food tonight or, worse still, he might even get rid of you. You must keep in his favour; we need your information desperately. Look, there’s a young hen, she’s stone dead, pick her up and take her back quickly.’

The dog went off and picked up the dead pheasant. With a last sad look at Sterndale he ran back through the bushes and as he went Sterndale could see the limp head of the pheasant bouncing stupidly against the side of Sam’s mouth. He looked away in anger.

At the front of the wood Brock had watched the proceedings in horror. He could see the Urkku near him very clearly; he had seen the man pull the trigger, had been deafened by the explosions and felt sickened as he heard the sound all around him of falling birds. The last horror was when the man had spotted an injured pheasant, a young cock, dragging its wing along the ground and scurrying to get into the bushes near Sam. The man had laughed gleefully and run after it, to the great delight and amusement of his friends, who had jeered and shouted at him as he waddled clumsily through the snow crying to catch the terrified bird. Eventually he caught it and, after bolding it up in triumph, had wrung its neck.

After this episode they had all proceeded to walk into the wood, still in their line, and Brock had had great difficulty in stopping himself from running out and attacking the man as he moved within paces of the sett. Slowly they had gone through the wood, passing the spot where Sterndale and the others were still hiding, and jumping over the brook to get to the other side. With every shot that came to him over the snow Brock felt a surge of pain and anger as he imagined the horror and hurt that some animal was going through. Time and again, the question ‘Why?’ echoed through his mind.

There were not too many more deaths that day. Three young and inexperienced rabbits, a buck and two does, had escaped Pictor’s control and ventured out to see what was happening; no sooner had they come out of their burrow than a hail of lead cut into them, leaving the two does dead and the buck writhing on the snow with his back legs in tatters. He had pulled himself with his front paws into the cover of the bushes, where Pictor had found him later, still dying, after the Urkku had left. He had suffered horribly for a night and mercifully died the following dawn.

The other losses were five woodpigeons and a hare which had been startled as the Urkku were making their way back through the field. Eventually they had gone, leaving the wood raped and violated after their crude invasion. For days it was impossible for the animals to forget about it; the smells lingered on and the air seemed full of death: one would come across trampled undergrowth or traces of the Urkku such as red cartridge cases still smelling of gunpowder or pieces of paper or the remains of the white sticks they used in their mouths. Sometimes there were the scattered feathers of a bird that had been shot or tufts of brown fur from a rabbit; mute testaments to the sufferings of their owners. The animals were frightened and nervous; they skulked in the shadows and ran to their burrows or flew off at the slightest noise.

As the line walked back over the field in the watery afternoon sun, Brock’s mind went to the baby Urkku in the sett behind him; it was hard to believe that he was of the same race. He went back down the passage, sad and weary, to find the baby crying frantically and waving his arms in the air.

‘It was the noise,’ Tara said. ‘I couldn’t keep him quiet. Could you hear him?’

‘No,’ replied Brock quietly. ‘No, I couldn’t hear him.’

‘Was it bad?’ Tara said, getting up and coming towards him. She rubbed her nose against his and then pushed the side of her head against his neck, trying to comfort him.

‘Yes,’ Brock murmured, ‘it always is; it seems to get worse. And what can we do? Nothing, Tara, absolutely nothing.’ He lay down on the earth floor with his back curled against the wall and went to sleep. Tara watched him tossing fitfully for a while and then she went back to the baby which was quieter now the Urkku had gone. Soon there was silence again.

Outside the sky had clouded over and it had become warm. In the late afternoon the rain began to fall and on the white snow the crimson streak left by the young cock slowly spread until finally it disappeared with the last of the snow.

CHAPTER VI

The seasons changed and the baby grew into a young boy. They called him ‘Nab’ which, in the language of the Old Ones, means ‘friend’, and he became as one of the animals of the wood. He understood instinctively the joys and sorrows, the sadness and the beauty of each season: the two seasons of stillness; cruel winter, a time of survival when the weak fell and the strong grew weak as the icy winds scythed through the wood, and friendly summer, a lazy time of plenty: a time of drowsy afternoon sleeps in the fragrant green shade under the bracken. Linking winter and summer and leading each gradually into the other were the two seasons of change – spring, with its atmosphere of excitement and anticipation, full of the magic of birth when the trees showed their delicate new buds and the earth covered itself with the glory of flowers – carpets of blue and yellow and pink and white on the woodland floor; and autumn, perhaps, if it were possible to choose, Nab’s favourite time when the wood turned to gold and the air was full of falling leaves and there was a constant smell of woodsmoke and the dankness of rotting vegetation; and above all a feeling of intense and beautiful sadness so exquisite that it made Nab’s heart ache as he watched the brown leaves drifting slowly in the wind down to the floor.

When he reached the age of three Brock and Tara built him a home in the rhododendron bush to the left of the Great Beech as he had grown too big for the sett. The layers of shiny leaves formed a large waterproof canopy over the large round open area inside the bush and when they had cleared some of the branches which ran through the middle there was plenty of space for the boy. Above all, it was well hidden: the branches and leaves were so thick that it was impossible to see through them from the outside although there were a number of places on the inside from which Nab could see out. The entrance to his home was at the back of the bush and it was only possible to crawl through it.

Brock and Warrigal would spend many hours in there with the young boy talking and explaining about the ways of the wood; and often the other animals would come in and spend time with him also, for the Council had decided that although Brock and Tara would always be his special guardians and protectors, he was also the responsibility of the entire wood and was not to be brought up as a badger, or any other animal for that matter, but was instead to be allowed to develop in his own way with all the animals helping him and teaching him in their own particular skills. Thus from Perry-foot the hare Nab learned the art of running and also a lot about humour. The boy laughed a lot naturally but with the hare he could play games like hide and seek and they would cuff each other in fun.

Pictor would come and have long serious talks with him about the art of organization and of running a community while from Sterndale the Fierce he came to understand the rightful place of pride and aggression. Often in the evenings Nab would be sleeping soundly in one comer of his bush when he would suddenly feel the presence of something and, waking up, would be thrilled to see the triangular face of Rufus the Red looking at him intently. After his initial doubts, the fox had become extremely fond of the boy, and now delighted in spending time with him, teaching him the arts of cunning and stealth. The boy would sit spellbound as the fox recited tales of adventure and excitement about the amazing and daring tricks his ancestors had used to avoid the savage packs of dogs which the Urkku sent out to kill them. Rufus also spent long hours teaching him how to walk without making a sound, how to merge with his background, how to use whatever cover was available and how to freeze whenever there was the slightest sign of danger. Most important of all, perhaps, he taught Nab the art of alertness: how to remain constantly on guard and what sort of sounds to listen for as signals of Urkku. While Rufus was talking to Nab, the boy would sit close and run his hands over the fox’s soft fur or bury his fingers in it and pull them backwards so that the fur stood up in little spikes on his back.

Nab also loved talking to Warrigal and sometimes, on summer evenings, Wythen himself. From them he learnt wisdom and wood-lore and they explained to him, slowly and gently, about the Magical Peoples and the Urkku and the relationship between them. The Elflord knew about him, they said, and it was he who was helping the animals to bring him up. At some time Warrigal would take him to meet the Elflord and they would have a long talk but that would not be for quite a few seasons yet. From the time he had left the sett Nab had been aware that he was not a badger and that in fact there were no other animals like him in the whole wood. The owls had explained to him that he was of a quite different type of creature and that his race lived separately in their own area some distance beyond the hill they could see at the far end of the fields at the front of the wood. They told him he had been found under the Great Oak one snowy winter’s night by Brock and that he had taken him in to look after him. Whenever he wanted to he could leave the wood to join his own race, they said, although of course the boy had no desire now to leave his home and his friends. They took him to the brook and showed him his reflection in the dark brackish water so that he would have some idea of what he looked like for he had not yet seen an Urkku. Whenever the shoot came they took him back down the sett where he stayed with Tara until it was all over. When he asked about the noise they told him that it was thunder and lightning and that they were keeping him in the sett to protect him from it, for they did not want to influence him in any way against his own race. This had all been explained very carefully to Wythen by the Elflord. ‘We must let his attitudes and opinions towards the Urkku develop entirely independently; they must come from him,’ he had said. And so, until he was slightly older, they had decided not to let him see the Urkku killing. There was another reason why they put him in the sett when the Urkku were around; although no one had come looking for Nab they were afraid that if he were found he would be taken away and they did not yet think that he had enough skill to be able to escape detection while men were in the wood.

Nearly every night Brock would crawl through the narrow passage into the bush and Nab would see two great white stripes appearing out of the gloom. They would then go out together and Brock would take him all round the wood looking for food. All the animals had told him what they ate and explained to him how to find it but Nab did not like the idea of killing his fellow animals and then eating their flesh, so his diet consisted of berries, fruits, toadstools (which he particularly liked), bark, grass and other plants of the wood. In the autumn he would go round the wood with Digit and the other squirrels collecting acorns, beechmast and the fragrant hazelnuts and these would be buried in one corner of his room to last the winter. He would also go with Bibbington the hedgehog to the dark damp places of the wood where the best toadstools grew and these would be gathered and hung all around the inside of the bush so that the air could circulate around them and they could dry for the winter. Bibbington told him to stay well clear of any white-gilled fungi because if he ate some types of those he would die a painful death, so he gathered only those which the hedgehog had assured him were good to eat: the yellow and ragged chanterelle with its delicate perfume and peppery flavour, the field and horse mushrooms which were his favourite and the oyster mushroom which grew in abundance on the old rotting silver birches in his part of the wood. Then there were shaggy caps, puffballs which Bibbington told him to ‘be sure and gather before the brown powder comes’ and boletus of all sorts which sprouted out of the decaying autumn leaves in their shiny oranges and dark browns and which the hedgehog had taught him to recognize by their tubelike gills and their smell. The dandelion provided him with both a vegetable all year round from its leaves and a root which, when dug up in the autumn, he could dry and use to add some variety to his winter diet. In spring he would rejoice in the abundance and variety of the new foods that were growing all around; the nutty flavour of the young hawthorn leaves, the slightly bitter wood-sorrel and the sweet young beech leaves which he would chew straight off the tree. He would also nibble the fresh young shoots of nettles and collect armfuls of the new season’s chickweed which, although he could gather it all the year round, always tasted better in spring. Sometimes he would scamper down to the big brook over the fields with Perryfoot and there they would spend the afternoon enjoying the nutty flavour of the young burdock stems which grew in profusion all along the banks and collecting watercress to take back and eat in the evening. Perryfoot had shown Nab another very useful plant which grew by the big brook in summer and which was always easily found by its scent; this was mint, which he used to add variety to the flavour of some of his more staple foods. It could also be dried if hung up and he would use this in the winter with his toadstools. Often he found large patches of meadowsweet in the same area as the mint and he gathered clumps to lay on the sleeping comer of his bush and to give to Tara for the sett. Ever since he had first been taken in and laid down on the pile of meadowsweet, he had found it difficult to sleep unless he had that fragrant scent in his nostrils.

A particular delight of late summer was to wander on a balmy evening with Brock and Tara to the blackberry bushes that grew round a hollow in the bank in the fields at the back of Silver Wood and to pick these juicy succulent fruits and eat them straight off the bush until they had had their fill. They would then sit for a while looking down on the wood while Brock told a story and the moon moved slowly through the sky.

There were other fruits which summer produced; rosehips, wild gooseberries and, a rare delicacy, wild raspberries. Sometimes, when the first leaves were beginning to turn brown and the smells of autumn began to linger in the air, Brock would take the boy off over the fields to a bank where bilberries grew and they would spend all night picking the delicate black berries off the small bushes and eating them. They would then gather as much as Nab could carry and take them back to surprise Tara who would ruffle the boy’s hair with her paw in delight.