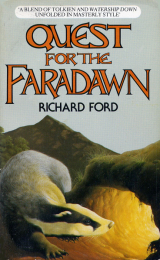

Текст книги "Quest for the Faradawn"

Автор книги: Richard Ford

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

Richard Ford

Quest for the Faradawn

Illustrated by Owain Bell

PANTHER

Granada Publishing

For Reena, Daniel and all the Animals

Spring 1982

CHAPTER I

It was still snowing in Silver Wood. All night large flakes had been falling relentlessly, covering everything until now every blade of grass had a thick round column down one side and every twig supported a white replica of itself. Brock looked up and was mesmerized by the myriad of white specks in the air. They seemed to come down directly into his eyes as if they were being pulled towards the earth by a magnet; and yet not hurrying, more a determined drifting. He shook himself and a flurry of flakes flew off, so he retreated further under the Old Beech until only his head was exposed from the hole amongst the great roots which formed a low wall at either side of the entrance to his sett. He was enjoying the night; there was that stillness and complete quiet that occurs when every sound is muffled immediately by a thick blanket of white, and despite the snow the sky was quite clear so that he could see almost to the pond in the field at the front of the wood.

Beech Sett had been in Brock’s family for generations, some said since Before-Man, and had in those times, of course, been right in the centre of the vast primeval forests that covered all the land. Now, since nearly all those forests had been consumed by man for his cultivating or living space, the fields had encroached almost up to the sett so that it was on the very edge of the wood and Silver Wood itself was only a short walk in length and width. The sett thus formed a useful look-out post and Brock had taken on the role of guardian of the wood, spending most nights looking out over the fields or walking along the edge while he looked for food. The other animals were happy with this arrangement because Brock had learnt to distinguish between real danger, when he would bark loudly two or three times, and a mere need for caution, when he would very often not alarm the wood at all but simply watch and wait until the incident was finished.

Tonight he was relaxed. On nights like this the great enemy almost never came out or if they did it was only to scurry past in the distance in that curious upright fashion of theirs, balanced on two legs with their heads down, and were very often gone as soon as Brock had spotted them. In a way he felt sorry that the peace and beauty of these nights were so seldom seen by them and he wondered whether this was one of the causes of their nature or the result of it. It was because of their hostility towards everything that they had been called, in the language of the Old Ones, Urkku or the Great Enemy.

Lost in these thoughts he was suddenly jolted into the present by a scent coming to him through the snow; he crouched lower and put his ear to one of the great roots at the side. Urkku were approaching; he could hear the unmistakable two-legged footfall, but there were only two and they were walking slowly and evenly. Keeping low, he peered hard through the flakes, which were now a nuisance as they got in his eyes and blurred his vision. Then he could see them walking round the side of the pond and starting to cross the big field at the front of the wood. They rested for a moment, leaning against the old wooden gate that led into the field, and then came on straight across it heading towards the sett. He wondered whether or not he should give the alarm; he rarely did at night, even when Urkku approached, because the few who came after dark rarely, if ever, caused damage and it was only if they carried the long thin instruments that blasted out death or that were used to dig with that he would alert the wood.

Every muscle tensed, his black nose-tip twitching, he watched as they came slowly forward, apparently now making for the stile into the wood which was only some thirty paces from the Old Beech. It was obvious that they knew the wood well for they did not hesitate or look around as most Urkku did but instead climbed over the stile and made straight for the Great Oak in the centre. To watch them now, Brock had to come out of the sett and pad slowly towards the little stream which ran across the middle of Silver Wood, from where he could see them clearly. He crouched in close against the bank of rhododendron bushes that went down to the stream and studied the scene. It was most strange. The first thing that struck him was that he did not have that awful feeling of fear which he nearly always felt whenever Urkku were near; somehow, all his instincts told him that there was no danger here and that, even if he were seen, no harm would come to him. Secondly, he now noticed that the taller of the two, the one with the shorter hair, was carrying a bundle which he handled very carefully and which was making a strange noise. The other one, who had much longer hair which was now flecked with white, simply stood quietly whilst the first placed the bundle down, right up against the oak, at the very base of the enormous trunk. He then proceeded to dig away at the snow and cover the bundle with the leaves and peat moss which he found underneath until only a small portion at the top was left from which Brock could hear strange noises, almost like those made by the river in the shallow places where it runs over pebbles.

Just as the man stood up, a peal of bells suddenly filtered through the still air. It was the church in the village calling the people to Midnight Communion on Christmas Eve. To Brock it was a death knell. The Midnight Bells came once a year and two days later came the slaughter. The wood must be warned. He turned back to the strange picture under the oak and saw the two kneeling over the bundle. The one with long hair placed her head close to the uncovered space, lingered there a second or two and then moved away. Then they both got off their knees and for a moment held each other in a way Brock had not seen before in the Urkku. He felt a great sense of tenderness and sadness radiate from them and in his own blood he felt a tingling sense of excitement and anticipation as he watched them walk slowly away, arm in arm, leaving the bundle there, under the Great Oak.

He waited until he saw them go back through the stile and begin to cross the field and then he began, very slowly and cautiously, to inch his way across the log which was the only way of crossing the stream other than going all the way round by the stile. The log was slippery at the best of times, being covered with moss and constantly wet from the water, but now, with a layer of snow on top, it was treacherous. He should have gone the long way round but he had always been a hasty badger and he was now so curious to examine the strange bundle that it would have been impossible for him to delay a second longer. His enormous front claws gripped tight either side of the log as he inched his way very slowly over it. He could see the brackish water beneath him, jet black against the white of the two banks, and he could see the way the snowflakes dissolved and vanished almost as soon as they hit the surface. He was nearly at the far bank now. The flakes had almost stopped falling and a familiar silver light began to reflect back from the water. He clambered carefully off the log and felt the snow soft and yielding again beneath his paws. This part of the wood was full of bracken and the snow was thick, so he had to be careful not to walk on a mound and fall right through; it was no use following the rabbit tracks either as the rabbits were so light they could walk over the treacherous bumps. He made his way carefully towards the oak, sniffing the air as he went, and every few paces he would stop and listen. The wood was bathed in moonlight now and there wasn’t a sound; nothing was abroad tonight and even Brock began to feel cold on his back where the snow had made him wet and where it was now beginning to freeze on his fur. Finally he arrived within a pace or two of the noisy bundle and was able to look at it closely. What he saw astonished him; from the only part that had not been covered over he could see a small round pink face which, when it spotted Brock, broke into a wide smile. Happiness shone from its two little eyes and, despite its strangeness, Brock felt an overwhelming, impulsive surge of sympathy which overcame his caution and astonishment. He moved closer and put his nose against the baby’s cheek. The face grinned even more and began to emit the strange gurgling noises Brock had heard earlier. He had only once before seen a creature like this; two or three summers ago two Urkku had come into the wood carrying one and had sat down and eaten right next to the Old Beech. They had still been there when evening fell and he had watched them closely for some time from the shadows of the entrance to the sett. He had reasoned it out then that it had been a human baby, and this little creature lying under the oak was unmistakably the same.

‘Well, well,’ he muttered to himself. ‘This is odd. What am I going to do with you?’ He looked curiously at the little face. His first thought was that it had been left temporarily and that the two Urkku who had brought it would come back for it soon; he realized now that they must have been its parents. But it was too cold to leave a young thing out in the wood and there had been something strange in the way the two had parted from it; something very final and sad yet beautiful. Brock felt all this intuitively, for badgers are known throughout the animal kingdom as the most sensitive of creatures; it is this, coupled with their wisdom born of centuries of history, that gives them their special place.

Now all his senses combined to give him that feeling of excitement which had come to him when he first saw the little bundle. In the recesses of his mind he was certain there were legends and prophecies which began with just such an incident as he was now witnessing and a thrill ran through him, making the hackles on his back rise.

He was still thinking about this when suddenly the night was shattered by an unearthly noise. The only time he had ever heard such a cry before was when the hares who lived in the fields round Silver Wood were injured by the Urkku with their death sticks. He looked down quickly to see the little face that had previously been one big smile transformed into a bawling horror. Brock concluded quickly that it was the cold; even he, with all his fur, was beginning to shiver. There was no time for thought; he must quickly get the baby warm and that meant he would have to take it back with him to the sett, where it would have to stay, at least for the remainder of the night. He gave a little snuffle of laughter as he thought what Tara, his sow, would say when he brought home a human baby: he had done some strange things in his time but nothing to compare with this. The baby was still crying away at the top of its lungs and Brock was afraid that soon all the creatures of the wood would be aroused and flock round to see what was causing the noise. The hatred that some of them felt for the Urkku was so strong that they would kill the baby on the spot, so Brock must quieten it down. He leant over it and, with his two big front claws around it, began to walk backwards, pulling the little creature along under his front legs with its body nestled against his chest. The warmth that came from his fur seemed to do the trick and it was soon gurgling happily again. There was no chance now of taking the short cut back across the log, so he began to go the long way round, through the new part of the wood and round, by the stile. The journey took a long time; Brock had to be careful not to get too much snow on the baby and to try to hold it up off the ground to keep it from getting damp and cold. Despite these difficulties, however, he enjoyed it; the baby kept putting its hands out and pulling at his fur or stroking the front of his leg and sometimes he would stop for a second or two and rub his wet nose under the baby’s chin or around its neck to which it would react by breaking into a wide smile and giggling. He met no other creatures on the way, for which he was extremely grateful, as it would not have been easy to explain exactly what he was doing walking backwards with a human baby tucked under his legs. Finally, just as the clear silver light of the moon began to give way to a pale yellow sun, he arrived back at the Old Beech, exhausted, and braced himself to face the barrage of questions which he knew would come from the rest of his family. Weary but satisfied he began to descend backwards down the hole with his little human friend gurgling and smiling, blissfully unaware of the part that destiny had chosen for it to play.

CHAPTER II

Brock’s forecast of Tara’s reaction to his ‘find’ turned out to be completely accurate. As he came into the main chamber bearing his little charge she simply got up on her hind legs, put her two front paws on her hips and rocked in silent astonishment from side to side. She had thought none of the antics of her boar could shock her any more, ever since the time he had gone off with their two cubs Zinddy and Sinkka to explore the streets of the nearby village and brought back with them a dog they had befriended. This dog, who was called Sam, still visited them at fairly frequent intervals with news about the village. His master was one of the men who waged war on the wood and Sam would bring them advance knowledge of when he and the others were coming. The friendship with Sam had therefore turned out to be very useful; but this!

‘This time you’ve gone too far. An Urkku; a member of the race that has persecuted and tortured our ancestors for generations, and not only ours but the ancestors of every living creature in this wood. Have you forgotten the tales of your great-great grandfather who was chained to a barrel and then had fierce dogs set on him to pull him to bits? And when he beat one lot, they set another lot on to him, and another, and another, until finally he was tom apart. And have you so soon forgotten the story that reached us of the killing of the entire sett over in Tall Wood that happened some ten full moons ago. They pumped some kind of poisonous air down the sett which made them vomit and which scorched their lungs so that they died a most horrible death. And this little thing here when it grows up will be a member of the Great Enemy! What are we going to do with it? How will we protect it from the other creatures in the wood, who hate the Urkku, if anything, more than we do? What will it live on?’

But somehow, when she looked at the helpless little creature lying on the earthen floor of the sett, it seemed so remote from the race of which she had been speaking that it seemed a different animal and her heart went out to it. It met her eyes with its wide smile and happy gurgle, putting out its little hand to grab at the air. She looked back at Brock, who had said nothing in reply to this avalanche of questions because there was nothing he could say. He was not the kind of badger who could leave a creature to die in the cold, and the only thing he could do was to bring it home. Besides, and he hadn’t explained this yet, partly because he didn’t quite know how to and partly because he wasn’t certain whether Tara would understand anyway, he had a feeling that the whole thing had somehow been meant to happen and that he was really only playing a part that had been chosen for him.

He went up to her and they rubbed noses; she closed her eyes with pleasure and Brock thought how much he loved her. He began to stroke her head with his front paw. ‘Our cubs aren’t due until the Awakening and I thought perhaps it could have some of your milk until then. We could have it in here with us until it grows too big and I am sure that berries and fruits and toadstools will be as tasty for it as they are for us. Don’t worry; it will be all right.’ He wanted to say more but he was so exhausted that his eyes had closed against his will and he began to drift off into the world of sleep. ‘Wake me at Sun-High,’ he managed to mutter and then he rolled over on to the heap of dead bracken that was piled into the corner and began to snore heartily.

Tara then took the baby over to the far side of their large round room, and laid it to rest on the cushion of meadowsweet she had collected and saved from last year for her own cubs. The smell of the meadowsweet tended to overpower any other smells and so was extremely useful for cubs and, she supposed, human babies as well. She then took off the various layers of clothing and material with which it had been wrapped and put them in a comer to take out and bury later on. There was one article, though, which she decided to keep; it was a beautiful multi-coloured silk shawl and Tara liked both the colour and the feel of it. In later years, she thought, the little male creature lying there so peacefully might be glad of some reminder of his past; some link with his heritage. This shawl she carried over to one of the walls of their room and, having dug a small hole in the wall, placed it in and then covered it with soil. By the time she had finished, the baby had begun to screw up his little face again and started to cry. ‘He must be famished,’ she thought and lay down next to him. She hoped that her teats were full enough with milk; if not, she would really be lost as to what to give him to eat. Still her own cubs were due not too far away, as Brock had said, so she should be all right. She pulled the baby up towards her and drew his face near her teats with a paw. For an agonizing minute or two nothing happened but then, to Tara’s intense relief, he began to suck. Physically he could have been one of her own cubs suckling, but emotionally she felt very strange; here she was, giving food from her own body to a baby human. It would have been odd enough if she had been suckling another sow’s cub but this was a different animal and an Urkku at that!

Yet despite this strangeness she also felt the warmth and tenderness that Brock had experienced earlier towards the baby, and she undeniably felt a sense of excitement and adventure as she sat cradling this strange head in her paw and feeling the baby suck.

He was soon satisfied and Tara laid him down carefully on the meadowsweet and covered him with strips of birchbark on top of which she laid dead bracken. He was very soon asleep and Tara set about cleaning the room; dragging out all the old and soiled bedding and putting new fresh stuff on the floor from the piles around the outside of the room. She occasionally ran her paws along the roof to clear it of cobwebs for the ceiling was latticed with the roots of the Great Beech and the spiders liked to build along and at the side of them. She finally went over to the entrance to the tunnel and ran her paws down the three large roots that framed the doorway; one at the top and two down either side. This had been done so often through the centuries that they were now a wonderfully rich dark brown colour and they shone and felt smooth to the touch. There were also little gashes down them where, on the darkest wettest nights, badgers had been unable to go to the scratching post outside the sett and so had sharpened their claws on the two old hard roots at the side. These scratch marks always reminded Tara of the past generations of badgers who had lived here. She wondered how they had died; how many had been killed by the Great Enemy and how many had simply gone peacefully in their sleep.

When she had finished her housecleaning she went through the door and up the short passage which led out to the wood. She put her nose out into the air and immediately had to screw up her eyes to protect them from the glare, for the sun was shining brightly from a clear blue sky and was reflecting up from the snow which lay in thick white smoothness all around. She could tell without looking that the sun was high in the sky, shining down through the branches of the Great Beech. It was time to rouse Brock. She backed down the passage (for there was no space to turn round) and had to wait awhile when she was back in the room to let her eyes adjust to the light. She went over to Brock and gently placed the tip of her nose against his. He awoke without a start, yawned, stretched and got up.

‘Hello,’ he said sleepily and then saw the baby. ‘Oh my goodness,’ he exclaimed as the events of the previous night began to come back and the full impact of what he had done dawned on him.

‘You wanted me to wake you at Sun-High,’ Tara said.

‘Yes; there’s a lot to do and not much time. I heard the Midnight Bells last night and you know what that means for tomorrow, so I must call a Council for tonight. And then there is this baby Urkku. Did you manage to feed him?’ Tara nodded. ‘Good. But some of them won’t like it and they may even try to kill him. They will have to be told, of course; we could never keep him secret when he gets bigger and it’s better to tell them now when he is so helpless and harmless than later when he begins to grow and look more like an Urkku. It’s a bad time, though, with the deaths and injuries that the Enemy will cause tomorrow. I must go and tell Warrigal to summon the Council and then we’d better have a talk with the rest of the sett.’ He went towards the door. ‘Everywhere looks very clean,’ he said, and vanished up the passage.

He emerged into the day and, like Tara, was almost blinded by the glare from the snow. ‘It’s too bright,’ he muttered, ‘too bright.’ But the warmth of the sun felt wonderful on his back and face. It seemed to spread through his body and fill him with new life. He barked quietly twice, looking up at the Old Beech. There was no reply. ‘He’ll be fast asleep,’ he thought. He barked again. Suddenly he felt someone behind him and turned round. It was Warrigal the Wise, standing blinking at him. ‘Don’t do that,’ Brock said. ‘You frightened me.’ You could never hear Warrigal; it was almost uncanny the way he could fly, even through branches and thick rhododendrons, without making a sound.

‘You want me to summon the Council,’ Warrigal said. ‘I heard the bells last night as well.’

‘Yes,’ said Brock. ‘Call them for tonight. And listen, Warrigal; there’s another matter which I want to raise and which I should like to mention to you briefly now.’ Brock felt it would be prudent to tell Warrigal about his strange guest and get him on his side before the others were told. Everyone admired Warrigal for his knowledge and what he advised was always regarded with respect by the rest of the wood, albeit somewhat grudgingly by some of the loners like Rufus the Red. He also felt that a private chat with him might clear his own mind on a few matters before the whole affair came out into the open. Badgers and Owls had been allies in the protection of the Wood as far back as the beginning of legend. The Badgers’ knowledge of the ground and the Owls’ command of the air made a good combination. They were both creatures of extremely ancient heritage and tradition, unlike some of the more recent additions like the pheasants and squirrels, and between them they could muster a great deal of knowledge and intuitive wisdom. Brock therefore felt that if anyone could understand his feelings of the previous night, it was this trusted friend. Besides, the fact that he had a baby Urkku down in the sett this very minute was quite a devastating piece of news and it was a nice change to be able to tell Warrigal, who always seemed to hear all the news first, something which he did not already know.

Surprisingly, and to Brock’s annoyance, the owl did not seem very shocked although he obviously had not known. He merely listened attentively, occasionally giving a long slow blink, while Brock told the whole story. When he had finished Warrigal looked down at the snow and shifted his feet slightly on the root where he was standing. He stood like that for a few seconds and then turned his head round, first to the right and then to the left, as if looking for anyone who might be listening. Then he stared hard at the badger. ‘Well,’ Brock said impatiently, ‘what do you make of it?’

‘If I am right in my belief,’ he said, with the air of someone who knew he always was, ‘then you, Old Friend, have been picked for a task which will go down in legend as the most significant event in the history of the animal kingdom. An Honoured Badger indeed; one whose name will live for ever along with the names of the great heroes of Before-Man and whose role in history may be seen perhaps as even greater than theirs.’

‘Stop, stop, for goodness sake,’ the badger said. He had begun to feel extremely alarmed; it was one thing being a Guardian of the Wood who shared responsibility with Warrigal and whose task it was to call the Council together for emergency meetings, but quite another to be told of all this stuff about legend and history and how he would become famous. The owl exaggerated, of course; he took everything seriously and tended to make the simplest of events take on significant proportions. Still he really did look grave.

‘But all I’ve done is rescue a human baby from dying of cold,’ he said, not really unaware of the enormity of that event but trying now to make it less important by talking about it as being less important. ‘Oh dear,’ he said, as Warrigal just stood there, looking at him.

‘Legend tells of an Urkku Saviour who arrives in the way your young friend arrived last night. I know no more than that. Your grandfather, Bruin the Brave, probably also knows of it but it is not a tale that is told often; partly because it is too unbelievable and partly because the ending has become lost in the mists of time. No one knows it,’ he added, remembering with a sigh that sometimes his poetic turns of phrase, of which he was extremely proud, were misunderstood. ‘The Elflord must be told; he, of course, knows of the legend and he will tell us how to proceed. I will see to that. In the meantime we must simply get the Council to agree to his remaining here, unmolested. Don’t breathe a word to anyone, except Tara, of the legend or of the Elflord. We must keep things as quiet and normal as possible, otherwise the Urkku might sense something different about the wood and begin poking around. Leave things to me tonight; I know how to handle the Council. Till Moon-High then,’ he said, and flew silently away.

Brock sat stunned, staring out at the field and thinking. He didn’t want to go back down the sett just yet; he needed time to collect himself. The mention of the Elflord had sent shivers of fear and apprehension down his back. He remembered his strange feelings of destiny and fate when he first saw the baby, but he had never dreamt that it would come to this. The animals all knew, of course, of the Kingdom of the Elves but very few of them had actually seen an elf, let alone spoken to one, and it was frightening to think that his name was to be made known to the Elflord. Warrigal had seemed very nonchalant about telling him, as if he ate with the Elflord every day but Brock didn’t really believe that the owl was that familiar with him. This was in fact the first time that Warrigal had mentioned the elves although, from certain oblique references in conversation, Brock had guessed that there was some contact between them and his friend. Still, it was extremely daunting to actually know of it; like everyone else in the Wood he had an uneasy fear of the elves even though they had never done him any harm. It was said that they had strange powers and could perform magic and that, although they normally used these powers for helping, sometimes they would use them to cause harm to an animal who had displeased them by threatening the stability of the wood. Stories were told of animals who had suddenly disappeared for no reason or who were found dead with no apparent injury. Brock therefore liked to keep these things at the back of his mind, and now, here he was, being brought to the attention of the elves, by what he was beginning to believe was an extremely unfortunate chain of events.

The sun was beginning to move down from the high place it had occupied in the middle of the day and had started to turn pale and watery the way it does on winter afternoons. The clear blue sky had given way to one streaked with wisps of grey cloud, so that now Brock was able to look at the expanse of snow which spread out before him without being dazzled.

The only sound to be heard was the three, evenly spaced ‘Toowitt-Toowoos’ of Warrigal as he glided, silent as a shadow, between the trees. This was the summons to the Council Meeting that night at which the leaders of the woodland animals would discuss tactics for the Killing tomorrow. The trees stood out, stark and black against the pale sky, each branch taking on an identity and character of its own and the twigs looking like the long bony fingers of an old woman. There was a feeling of utter calm in the scene before him which gave him a strength and resolve he had never before ex-perienced; perhaps because he had never needed it. He turned slowly and made his way back through the earthen passage into the familiar sett, with its comforting atmosphere of home.