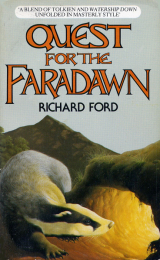

Текст книги "Quest for the Faradawn"

Автор книги: Richard Ford

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

CHAPTER XIII

Beth was in the middle room decorating the Christmas tree. They were late doing it this year because everyone had been so busy; her father at work, her mother with the new baby and she herself had been unable to find the time because of all the little things that need to be done at this time of year; buying presents for the family, visiting grannies and grandpas and seeing friends. There had also been a lot more for her to do in the house because her mother’s time seemed totally taken up by little James and she had found herself making meals, washing and cleaning somewhat more than usual. So now it was Christmas Eve, snow was on the ground outside, the atmosphere in the house was full of excitement and anticipation and she was hanging tinsel and coloured balls on the tree. Life was perfect; and yet she was not content. She had not felt truly at peace with herself since the spring day when she had come face to face with that extraordinary boy down by the stream. She had told no one and the secret had burned away inside her with the effort of not telling but to her surprise she had succeeded in keeping it quiet. Something about the boy had sparked off within her a restlessness that had troubled her ever since and she had taken to going for long walks by herself through the woods and fields; at first in the hope of meeting him again but, when this seemed to become more and more of an improbability as the days passed and there was still no sign of him, she had simply walked because it was only while she was out amongst the trees and fields that she felt content. Eventually though, she had fought this feeling within herself and had settled down to her school work again, which had begun to suffer terribly from her inability to concentrate on any one thing for more than a few seconds at a time. She had then become more like her old self to everyone around; her mother, her father, her elder brother, her teacher and her friends. Once more she was a pretty, studious, diligent, polite and cheerful little girl. She was pleased because she loved all these people and it hurt her to worry them but she knew that it was only an act, a facade put up for their sakes, and that behind it she still burnt with energy and felt as restless and bored as before. Still, she hoped that if she worked at it hard enough, the feeling would eventually go away and, as time went on and the memory of his face and those dark eyes began to fade, she even started to believe that she was succeeding. She had been to some parties this autumn and winter and had quite enjoyed them and was due to go out tonight to a dance in the Village Hall. She was looking forward to this and as soon as the tree was finished she would go upstairs to her bedroom and get ready.

However, just a few weeks ago she had had a dream; it was not an unpleasant dream, in fact quite the reverse, but it had brought all her old feelings of unrest flooding back. She had dreamt of his face, and it had been as vivid in the dream as if he had been standing in front of her; his vibrant eyes had searched hers the way they had that day and she had felt strangely drawn to him. Then there were disconnected snatches of other pictures; in one of them she was walking at his side along a mountain path and they were followed by a dog, a badger, a hare and a large brown owl; in another he was giving her a ring, a beautiful ring of a deep golden amber with silver wisps inside it.

These dreams had recurred almost every night since then and, although the images of his face and the ring remained constant, as did the animals, the others changed so that in some of them they were walking along a beach and the sea was crashing against the shore and in others they were in a marsh, lonely, desolate and lost in the middle of the night. The dreams occurred so often and were so real that she sometimes felt as if they were her real life and it was her daytime life that was a dream. She began to exist in a strange twilight world where the two became confused and intermingled to such an extent that she was frequently surprised to find, during the day, that she was not with the boy and the animals and she found herself referring to incidents in her dream life when she was talking to her mother or to friends.

Now it was Christmas and she was hoping that the excitements and joys of this time would help her to return to normality. She hoped for this and yet the strangest thing of all was that although the dreams made her muddled and uneasy she longed for the end of the day when she would once again inhabit their world and be with the little band of companions as they journeyed through the countryside.

She was just putting the finishing touches to her arrangement of the lights on the tree when her mother called through to her from the kitchen.

‘Beth, lay the table would you, dear? Your father will be home soon and the meal is almost ready. Get some sherry glasses out for us; you can have a little glass as well.’ There was a pause and Beth heard the clatter of pans in the kitchen. ‘Have you finished the tree? I suppose we’ll have to get your father to look at the lights again. They never work; it’s the same every year.’

Beth switched them on at the plug socket and nothing happened.

‘No, they haven’t come on, Mummy,’ she said, and stood back to admire her handiwork. ‘The tree looks nice though,’ she called.

She went over to the big oak dresser which stood against one wall of the room and pulled out the cutlery drawer so that she could lay the table. The mats she fetched from a ledge which ran along the bottom of the dresser and she then walked across to the middle of the room and began to lay four places on the large oval dining table which smelt of polish and shone in the flickering light of the candles which she had lit and placed in the centre. Upstairs she could hear sounds of movement as her elder brother who, at fifteen, was two years older than her, though he sometimes acted as if it were ten, got up from the desk where he had been reading a book and walked over to the door of his room.

‘What time is it, Beth?’ he shouted down.

‘Five o’clock,’ she told him. ‘Come and fix these lights before Father gets home.’

‘Fix them yourself.’

‘Pig!’

‘Children, don’t bicker tonight. I’ve got enough to cope with feeding James and getting the meal ready without you two going on at each other.’

Beth finished laying the table.

‘I’ll go upstairs and get changed now,’ she called through to the kitchen, ‘so that Daddy can take me to the dance as soon as we’ve had the meal.’

‘All right, dear. I’ve ironed your new dress; it’s over the back of the chair in your room. Don’t be too long; Daddy should be home any minute.’

The girl walked across to the open wooden staircase which ran up one side of the little room. She loved this room; this was the old room, the one that had always been here ever since she could remember, unlike the new room at the end which had been built as part of an extension to the house four years ago and which, although it had been designed to be in keeping with the rest, she had never taken to as being a part of it. It was too well-planned and neat. But the old one seemed to have grown out of the earth itself and she never felt shut in inside it because it gave her the feeling of being outside in the woods. When the winds blew and the rain poured down on winter evenings she felt as if she were underground, and the rough and gnarled black oak beams in the ceiling which glimmered in the firelight were the roots of a large tree. Even when her restless moods were on her she felt content here and would often sit alone, reading, when the others had gone through to the new room to watch television. The magic of the books she read seemed to be intensified by the room with its flickering shadows and atmosphere of secret history.

Beth had reached the stairs and was about to start climbing them when her eye was caught by a movement through the window in the wall behind the stairs. She stopped and bent her face to the glass to look outside. There, to her disbelief, was the face which had grown so familiar to her in her dreams, the face of the boy from the stream. She closed her eyes, counted to ten and opened them again to make sure it wasn’t a dream but the face was still there, looking at her, the smouldering eyes searching into her soul. Now the dream had become reality and she felt strangely calm for she had been with the boy so often in her dreams it was as if she had known him for a long time. This was a moment she had lived through on countless occasions in the twilit world she had been inhabiting, so she knew exactly what she would do.

Outside, Nab was a mass of doubts and uncertainty. He had been to the first window and when he had seen no one in that room he had moved cautiously along to this and had been standing watching Beth for quite some time while she set the table. At the sight of her again, he had been unable to do anything except stare, transfixed, as she moved around the room. She was of course older than that spring day when he had first seen her and she had begun to acquire a grace and delicacy in the way she moved which captivated him; the way her hair flowed around her face as she walked and the way she tucked the sides behind her ears so that it would not get in the way when she bent her head to put the cutlery on the table; the way she had folded her arms when she called upstairs and the way her lips had set when the voice came back down; and the way she had stood talking to her mother with both her hands tucked in the back pockets of her jeans. There were a hundred little mannerisms, indefinable and unconscious, all of which came together to weave a spell under which Nab became entranced so that when she looked through the window and he knew she had seen him he was unable to think what he should do. Then he remembered the ring and he fumbled under the layers of his garments until he found the second locket on the belt. With hands that were shaking in confusion he pushed the catch, the top sprang open and he placed his two first fingers inside to draw it out.

When she saw the boy delicately hold out the ring to her on a hand that was dark and seamed with use Beth knew without any doubts that she had to go with him. It shone with the colours of an autumn morning, just as she had seen it in the dreams. She looked up at the boy’s anxious face and their eyes met. She knew he was nervous and tense, as he had been when they first met. He stood there, ragged and wild, the breeze gently moving the layers of bark that hung around him and blowing his hair over his face so that only his eyes were uncovered. He was as a wild animal; the tension in his body filling him with the energy which is at the source of life itself, magnetic and powerful, his entire being tuned to the rhythms of the earth and the sky. At the same time his eyes, which burned so desperately into hers, were full of sadness and mistrust, of constant persecution, but deep within them was an anger, the perception of which frightened Beth, so resolute and enormous did it appear. ‘I would not like to be the cause of that anger,’ she thought to herself. ‘It would destroy the world.’ She did not know it and neither did Nab but what she was seeing was the fury of Ashgaroth.

Their eyes held each other for a long time and, because it was the only way they could communicate, worlds passed between them. Suddenly Beth became vaguely aware of her mother calling from the kitchen. It sounded far away as if it came through a room filled with cottonwool but Nab heard it and his face froze with tension.

He watched her, through the window, as she called something to her mother; then she turned back to him and placing her finger over her lips in the universal gesture of silence she pointed up the stairs and then down again, and then out to him.

While Nab was thinking about this she began to climb the stairs and he then realized what she had meant. He crouched down under the window up against the back wall to wait for her.

Beth passed the door to her brother’s room and opened the door to her own which was next to it along the corridor. Thankfully she closed it behind her and went to sit on the bed for a minute or two to gather her thoughts. Now that the boy was no longer in front of her she began to wonder again whether it was just one of her dreams; even if it was not, was she mad to think of running away on this freezing snowy night with a boy whom she had known for no longer than ten minutes in her whole life. And the boy! The more she thought about it the more incredible did the idea seem. Every possible rational argument was against it and there was no way in which she could logically justify what she was thinking of doing. Then she remembered the ring and somehow the thought of it filled her with a strange feeling of security. That had been no mere coincidence; neither had it been part of a dream. Something was calling her and she had to go; what it was she did not know but that it was there she could not doubt. There was no real choice, for if she did not go she would be unable to live with herself for the rest of her life.

With her mind resolved into certainty she began to think about what she should take with her. She got up and went over to her little dressing table in the corner and ran her hands slowly along the front edge and then, when they reached the two corners, back along the sides until they came to the wall. She loved this dressing table; it had been given to her last Christmas and was the first big thing of her very own that she had ever had. She sat at it for hours, staring into the mirror and thinking about everything and nothing. At the front was a small crocheted woollen mat that had been made for her by her grandmother and given to her last birthday, and along the back and sides were all her bric-a-brac and personal things; bottles of different types of perfume and scent, hairslides, tubes of make-up, bottles of nail varnish. In the middle was a wooden jewellery box, made for her by her father when she was a little girl; she opened it sadly and looked at the jumble of rings, bracelets and necklaces that spilled over the edges on to the surface of the dressing table. Pushed into the frame around the mirror were rows of little photographs; some were with friends from school and there was a column of four that had been taken with a boy she had known. He was the son of some friends of her parents and had taken her a few months ago to see a film in the city, miles away. When they had come out he had taken her to a restaurant and they had had a meal with some friends of his. She had learnt a lot about herself that day and had lain awake in bed all night, thinking. In this way, as she looked at all the things on the dressing table, fragments and images of the past flashed through her mind.

She was leaving them now and, although for months she had been dominated by insatiable restlessness, now that she was actually going, she was unable to leave without sadness. She smiled ruefully to herself at all the things she saw; there would be no need for any of them now, she thought, and turned away quickly lest she start to cry. She must write a note for her mother and father; they would be bound to worry but perhaps she could ease their fears a little. She picked up a pen and paper but the words she searched for did not come; how could she express what she felt and explain why she was going away? She sat wrestling with the sentences and then suddenly, from nowhere, they came and seemed to write themselves. The words were the words of poetry, gentle magic words filled with awe and beauty so that when her parents later found the note pinned on to the front of the dressing table they were glad, even in their sorrow at losing Beth, for there was no doubt in their minds but that she was safe and happy and would always be. They knew, for they were of the Eldron.

When the note was finished she opened the drawer of the dressing table and out sprang her clothes. She selected three tee-shirts; green, red and black, and three jerseys, starting with a fairly closely knit cardigan and ending with the enormous chunky polo neck sweater which she had bought this winter; it was a dark muddy green colour and had a red and white patterned band around the chest. When she had put these on, she got a large brown corduroy jacket from the wardrobe which stood at the side of the dressing table and finally, over everything, she put on the dark brown tweed cape with the lion’s head fastening which had been her grandmother’s. Beth had been given it on her tenth birthday after admiring it constantly every time she had gone for a visit. It was perfect, she thought. Apart from the purely practical point that it was the only thing that would go over the top of all these layers of clothing and that it was wonderfully warm, she felt that it was the right sort of thing to be wearing for walking over moonlit fields; she had always had a feeling that there was something special about it, an aura of mystery and magic, and for that reason she had never worn it before, preferring to wait until an occasion which would warrant it. She placed the heavy cape over her shoulders, pulled the fastening chain across from the lion’s head on one side to the metal tongue behind the head on the other and slipped it over. The cape fell around her and lay, draped in heavy folds, all the way down to the carpet on the floor. She buried her hands amongst the rest of the clothes in the drawer, found the fawn coloured woolly hat she had been looking for and, when she had put it on, pulled the hood of the cloak up and was ready.

She took a last look in the mirror and then turned away to go towards the door. The pretty little red dress that her mother had ironed for her ready for the dance lay over the back of a chair on the other side of the room; it’s funny, she thought, how only half an hour ago everything had been so normal and ordinary. The dress looked lost and forlorn lying there waiting to be put on and Beth too felt sad even in her excitement. Then she suddenly remembered the Christmas presents and she reached under the bed, where they had been hidden, and laid them out on top. Luckily she had wrapped them last night and put on little cards with names. There was a pewter bracelet for her mother and a pen for her father; a record for her elder brother and for the little baby James she had bought a big brown teddy bear. Both grandmothers had been given the same to stop possible accusations of favouritism, a wildlife calendar, and both grandfathers had been given socks. The sight of all these presents laid out in a row in their gay Christmas paper and the thought of giving them out around the tree tomorrow morning was almost too much for her and tears began to run down her cheeks.

She had to go now, without thinking any more about anything. Resolutely she made for the door, opened it and walked out without once looking back. Silently she walked down the stairs and went over to the cupboard opposite the back door where she kept her Wellington boots. There was a pair of thick white woolly socks pushed down one of them and she put these on before she pulled the wellingtons over her jeans. Then she heard, with a stab of pain, the familiar miaow of Meg and felt the black furry body of the cat rubbing up against her leg. She bent down and picked her up and Meg closed her eyes and began to purr loudly. Beth held the cat closely to her and then lifted her up so that they were face to face.

‘Look after yourself, little friend,’ she said softly. I'll never, ever forget you, ’ and she gently put the cat down on the floor where she sat upright looking at Beth. ‘I’ll have to go now,’ she said, and without daring to look at Meg again, she put her hand on the back door knob and turned it. The door creaked as it opened slowly.

‘Is that you, Beth?’ her mother called from the kitchen.

‘I’m just going out to get some coal for the fire,’ she shouted back, her heart thumping with the fear of being discovered. How would she explain all the clothes she was wearing?

‘Well don’t be long, dear; your father will be home soon.’

As she stepped outside, the icy air of the freezing winter night hit her and she shivered involuntarily. Then she slowly shut the door and it was only when she removed her hand from the knob that she realized the full impact of what she had done. She put her hand back on it as if to make sure of an escape route if things went wrong and looked frantically in the dark shadows under the window for the boy. ‘No, it was all a dream,’ she thought, and suddenly felt very stupid. But then, as she was about to go back inside, she saw him stand up and move nervously towards her. At the sight of him all her doubts and fears instantly vanished; this was her world now and he, whoever he was and whatever he did, was her life. He stopped unsure of himself, and she began to walk slowly towards him. When she was just a pace away she smiled and then with a sudden rush of emotion she flew to him and flung her arms around his neck. Tightly she clung to him and the more she held him the more she found that all the restlessness and the anxieties she had suffered since she first met him flowed away. While holding him like this, she was also able to forget her worries and her deep sadness at leaving home and leaving all the people she loved. This was the only way they could communicate; through her body she was trying to transmit all these emotions and fears to him and, along with the fears, the great joy and happiness she felt at seeing him again and being with him. It was as if a dam, against which water had been building up for three years, had suddenly burst and all the water was gushing out.

Nab, who when the girl had first put her arms around him had been unable to understand what she was doing and had grown even more tense and afraid than he already was, now began to relax and respond by slowly lifting his arms and closing them around her. Like all animals his senses were very highly attuned to emotions and he understood what she was trying to tell him, so that he equally, in the only way he could, tried to reassure her and comfort her in her uncertainty and sadness. Beth, when she felt his body relax and his arms around her, could have cried for joy and relief. For the first time since she had been very young she felt totally at peace with herself; the cold night air that she breathed went to her head, and the trees in the back garden which stood stark and winter-bare silhouetted against the dark sky, their twigs like the long bony fingers of an old wizard, seemed to be her friends and guardians.

They stood like that for a long time in the shadows at the back of the house, each trying to reassure and comfort the other; so lost in their own world that nothing mattered except the moment which was timeless. Then suddenly their world was shattered by two great beams of light that cut away the darkness on their left then moved across to catch them in its glare for a moment and finally vanish inside the garage to the right of the cottage.

‘Daddy’s home. We must rush,’ she said and, although Nab could not understand what she was saying, he detected the note of urgency in her voice and in any case he also felt that they should leave as quickly as possible. As they heard the noise of the car engine stop they were halfway across the back garden and by the time the garage door slammed shut they were passing the belt of trees under which Brock had been waiting anxiously and with not a little irritation for them to come away from the house. How much longer they would have stood there if the car had not arrived he did not know nor did he like to think but he was thankful that Nab was here at last, with the girl, and they were safe.

Beth wondered what the boy was doing when he uttered some sounds in the direction of the trees but when the badger emerged stealthily from the shadows she was not altogether surprised as she had seen him so often in her dreams. Nevertheless she was very excited; despite all her time spent in the woods, particularly at dusk which was her favourite part of the day, she had never before seen a live badger. Now here was one walking beside her and never even giving her a sideways glance. Then she saw the owl perched on the fence apparently waiting for them. She heard the boy make some more noises to it and to her astonishment the owl responded. Then the truth occurred to her; although he could not speak the human language he was able to speak in the language of the animals and they likewise spoke to him. The noises that he made to her were in their language and that was why she could not understand them.

They were just crawling under the wooden fence when they heard the crunch of footsteps walking along the gravel drive from the garage to the house and then the sound of the front door opening and closing and, muffled from inside the house, the traditional evening greeting from her mother to her father and his to her. ‘Hello dear; had a good day?’ ‘Yes thanks; and you? Any post?’ Then a pause while he looked at any letters that had arrived. ‘What’s for supper?’ he would add finally before he went up the stairs to change out of his work clothes.

Beth heard each piece of the familiar jigsaw pattern of her life and wondered whether it would be for the last time. The security of that routine had been the foundation of her life; now she was scrambling up the hill with a badger on one side of her, this strange and beautiful boy on the other and a large brown owl flying low ahead of them over the field leading the way. Where she was going she did not know nor even why, but now that she was on the way she was hardly able to contain the exultant feeling of joy and freedom which surged through every part of her body. And then finally, when they were at the top of the hill, she heard a different note in the house and knew that the jigsaw, for a while anyway, had been broken. It was the sound of her father she heard, calling down in panic to her mother, ‘Where’s Beth? Have you seen her?’ and then the back door flying open, releasing a stream of light into the darkness, as her mother dashed out to see whether she was still by the coal-shed and stood framed in the doorway shouting her name out loud over the fields. ‘Be-eth, Be-eth,’ a long drawn out cry which cut the girl through with guilt and remorse and almost made her run back down and tell them she was all right and safe and that she loved them. But she knew that she could not. She had caught hold of Nab’s shoulder when they heard her father shout and they were both standing now looking down at the scene of panic below them. Nab understood the pain she was feeling; it was as if he were to leave Brock and Tara, never, perhaps, to see them again, and he found her hand where it lay hanging limp and cold by her side, and clasped it in his. She turned to him and her eyes were misty and sparkling with tears and once again they held each other tightly for comfort until the voice of her father, calmer now, came down to her mother calling her in to look at something. He had found the note in her bedroom. Beth could do no more; she turned away quickly from the sight of home and, still holding each other’s hand, the two walked slowly away over the frozen snow until they found Brock and Warrigal waiting for them under a large ash tree at the side of the field. Then the four set out under the moonlight for Silver Wood.