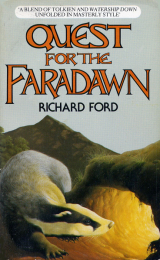

Текст книги "Quest for the Faradawn"

Автор книги: Richard Ford

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

The animals wearily and reluctantly turned away and followed the elf as he took them back across the bracken and heather of the headland until they reached green meadows full of sheep where they had to climb over many stone walls as Faraid led them once again towards the Marshes of Blore. When they reached the edge of the marsh it was late afternoon and the storm had blown itself out. Everywhere was dripping with wet and the grass smelt fresh and clean. The light they had seen earlier on the horizon had now spread to fill the sky so that everything was bathed in a gentle golden light. Looking up, the animals saw that the sky had almost completely cleared and lots of little snow-white fluffy clouds were racing across the blue.

Nab asked Faraid whether they could rest awhile before they entered the marsh but the elf thought it advisable to press on as it was likely that the Urkku had now left Elgol and were back amongst their people. He told the friends what the Urkku had said outside the cave about the ‘pack of animals’ and the ‘two runaways’.

‘Every Urkku in the land will now be looking out for you,’ he said, ‘and if you are spotted they will pursue you relentlessly until they find you. Dréagg is feeding them with lies and rumours which will fester and grow as they spread until the stories of your misdeeds are known by all. It is the way the Evil One works; he uses deceit and trickery to play on the minds of the Urkku. You are near the end of your mission and he will do everything to stop you. If you were careful before, now you must be doubly so, for he will use the goblins again and they have the power to transform themselves into Urkku when they wish so that they may work with the Urkku against you. There is, then, no time to waste.’

It took them until the following evening to cross the marsh and somehow this time it did not seem so terrifying. They saw no goblins and although they went along the same path as that by which they had travelled before there was no trace of Golconda nor of the tree on which he had been left. They emerged out of the mists of the marsh into a calm golden evening at a place some way from that by which they had entered when they came. They stood for a little while looking out over a landscape of rolling foothills gently sloping upwards towards distant moors. It was the end of spring and the beginning of summer, and the trees, huge elms and sycamores and ash, were covered in a multitude of different greens from the deep dark emerald of the elms to the delicate lime green of the ash trees. They towered up into the blue, their leaves gently moving in the evening breeze; rows of them like giant guardians of the earth stretching along the narrow valleys between the hills where little streams gurgled their way down through banks laden with primroses and bluebells and little green shoots of bracken poked their way up through the rich dark peat moss.

Faraid turned to them and pointed to a little hummock on the skyline.

‘There is your first Scyttel. From there you will know your way to the lair of the mountain-elves by the feeling of the Roosdyche. Farewell, and may Ashgaroth guide you safely to the journey’s end.’

So saying he turned and quickly vanished into the mists of Blore so that even as they looked after him, he was gone. Then they looked at one another in silence for a few moments before Perryfoot pricked up his ears.

‘Come on, ’ he said. ‘It’s spring and the earth is full and green, ’ and he set off up the slope with the others following behind.

CHAPTER XIX

It was a perfect evening as they made their way up the green bank alongside the stream towards the Scyttel in the distance. The air was warm and scented with bluebells which covered the ground under the giant trees in a blue haze, and further down, near the stream, there were splashes of vivid orange from the marigolds that sprang up in clusters wherever there was a marshy piece of ground. The sun was almost down behind the far hills but it seemed to shine with a particular fierceness as if hoping that its light would last after it had gone so that its warm, magic glow flooded the little valley along which they were walking and sent shafts of gold through the huge green leafy tree canopies overhead. Then, suddenly, it was gone and the shadows of dusk filled the valley and soon the dew fell everywhere and their feet became wet as they walked through the long grass. The dampness on the ground filled the air with the smell of wet green leaves and grass: the unmistakable smell of a spring evening, and the animals drank it in as if it were elvenwine and indeed it had the same effect, filling their tired bodies with fresh energy and vigour so that they felt they could have walked for ever. The air stayed warm late into the night and a little breeze came up, blowing gently against their faces as if it was trying to cleanse their memories of that last morning on Elgol. The agony of walking without Sam was almost more than they could endure. They would keep forgetting he was not there and then, on turning to speak to him or look for him, would once again be hit by the shock of realizing what had happened. If it was worse for any of them, then it was worse for Brock, because he had known the dog the longest and had walked alongside him for the whole of the journey. Nab had asked Perryfoot to walk with him and the hare had willingly obliged but it did not seem to have helped much; the badger would walk along with his head down and then suddenly look up and stare at Perryfoot with blank, uncomprehending eyes until he remembered and then his head would once again slump down and he would urge his tired body to resume its shuffling gait over the grass. First Bruin, then Tara and now Sam; they had all felt the losses terribly, particularly Nab, whose life had been so intertwined with Brock’s, but it was undeniably hardest on the badger, for two of them had been his family and one his best friend and Nab now had Beth to live for so that he was able to look forward: for Brock the past had died and the future was uncertain and lonely.

They reached the mound that night and slept under the shade of a huge sycamore until the following evening when they awoke feeling refreshed after a deep dreamless sleep. Even Brock felt a bit better as they started out once again towards a range of mountains in the far distance. They were quite high now and they walked through green fields cropped short by grazing sheep which were criss-crossed by white stone walls. High up in the clear blue sky larks sang while lower down plovers dipped and swooped over the ground and curlews sent out their liquid warbling cries into the still evening air. Behind them, from the valleys through which they had walked the previous night, they heard the occasional screech of an owl or the bark of a fox or else a cuckoo calling out his spring song. The daisies and dandelions which in the heat of the day had sprinkled the meadows with whites and oranges were now closing up and drawing their petals in for the night.

On they walked throughout the remainder of the spring; then summer came, and the hot sun beat down on them, making their throats dry and parching their mouths so that they walked from stream to stream, but as the days wore on and rain refused to fall the ponds and streams got low and the water that was left in them was brackish and musty. They were still making for the far mountains, which appeared hazy and bluish in the distance, but they had dropped down again now into the lowlands where there was little if any breeze to relieve the unrelenting heat which poured down from the blue sky into the lanes and between the hedges along which they cautiously made their way. They slept only in the afternoons now for Nab was anxious that they should move as quickly as possible and he and Beth each carried a share of her winter clothes: the brown cape and the jerseys which had helped her to survive the cold. Nab had wanted her to bury them under a hedge somewhere but she had been adamant in her refusal.

‘They’re all I have left of my old life,’ she had said, ‘and of my home. I could no more part with these than you could throw away your bark from Silver Wood.’

So, because he loved her, he reluctantly agreed and had ended up carrying her heavy cape and two jerseys while she took the remaining one and thanked him for being so thoughtful and kind.

It was in the height of summer, one hot morning when they were trudging along a dry dusty cattle track through a field, that they saw for the first time a thick black column of smoke rising in the distance. It went straight up in the humid windless air and the animals could smell the acrid stench of its fumes from where they were standing. They stopped still and looked at it; they had all seen smoke before from the chimneys of the Urkku but this was somehow different. The smoke was blacker, thicker and more dense, and the smell was sickly-sweet and nauseating; it reminded Beth of the smell caused when people put chicken carcasses on fires to burn them after the Sunday dinner.

‘Look, there’s another,’ Brock said, and he pointed to a thicker column round to their right and as they looked around they saw more and more until there must have been a dozen fires, all with their black plumes drifting up into the sky. There was something ominous and evil about them and Nab felt a chill go down his back as he watched.

‘Come on,’ he said, ‘we can't stay here all day.’

‘What are they, Nab?’ said Beth.

‘I don’t know but there’s something about them which makes me afraid. We must move on.’

‘It’s almost Sun-High,’ said Perryfoot. ‘Couldn’t we stay here for the afternoon by the hedge? It seems as good a place as any.’

Nab looked at Warrigal and the owl spoke.

‘It may be our last opportunity to rest for quite some time. I think we should stay here and move on in the early evening.’

So the animals walked over the field towards a thick hedge which ran along one side. Growing in the hedge were a number of large oak trees and they settled down in the shade of one of these, huddled around the trunk with Warrigal perching on one of the high branches to keep a watch for any signs of danger. It was beautifully cool in the green shade of the oak and they were soon asleep.

When evening came and the dusk began to fall they awoke and moved on. In the darkness they could not see the black smoke fromthe fires but they could smell them and occasionally they caught sight of red flickering flames in the distance and heard noises of shouting and crying coming from the direction of the fires.

As dawn arose they were walking along a little grassy ridge with wooded heathland on one side and meadows on the other. The ground was blackened and scorched so that there was very little grass left in the field and all that remained of the heath was an expanse of charred black scrub and bushes. The smell of burnt wood was everywhere and their feet became sooty as they walked. They could see now that the countryside all about was the same and the air was full of black smuts.

It was mid-morning when they saw the Urkku. They had been making their way up the scorched slope of a little hill when suddenly they froze at the sound of two shots from the far side followed by ferocious guttural shouts as if an argument was going on. They crawled through the blackened grass until they could just see over the top. There was quite a deep valley the other side and halfway up the far slope stood a number of Urkku, all with guns, yelling at one another. On the ground were some dead rabbits and the Urkku seemed to be in two groups, one on each side. Beth looked in amazement at the men, for she had never before seen any like them. Their clothes, if that is what they had once been, hung off them like strips of dirty rag and their bodies were so emaciated that the ribs stuck through their puny barrel chests and the skin hung in loose folds. They were wearing what appeared to be trousers and out of the bottom of these protruded thin bony ankles like matchsticks, and bare feet. She looked in mounting horror at their faces and was transfixed by what she saw. The hair was long, dirty and matted so that it hung down in tangled knots or else stuck out in greasy spikes, and beneath this filthy thatch, deep-set sunken eyes stared out of a face so covered in grime and dirt that as they shouted their teeth seemed to flash silver in the sunlight. Their cheeks were sunken and hollow and the cheekbones appeared to be all that held the covering of skin from falling away. Beth held her nose and had to stop herself from retching when the stench from their bodies, exaggerated by the heat, was carried over in the breeze.

The cause of the argument seemed to be the rabbits for each group was pointing at them and then gesticulating wildly and shouting. Suddenly an Urkku from one group ran forward and, flinging himself on one of his adversaries, began wrestling with him on the ground. They rolled around spitting and biting and kicking and a cloud of dust rose up around them. The others transferred their attention from the rabbits to their mauling companions, each side yelling encouragement to its own until finally one of them, whose hair under the grime was a ginger colour and who looked the bigger and stronger of the two, grabbed hold of a rock on the ground and brought it smashing down on his opponent’s head. There was silence while the one who had been hit went still and rolled back on to the grass with blood pouring from his head. The ginger one was just disentangling himself from his grip when one of the other group shouted at him and, raising his gun to his shoulder, shot the victor in the chest and sent him flying back to end up lying on top of his opponent. The friends then looked on in amazement as the two groups began blasting away at each other from where they were standing. It was over in seconds and the crashing noise of the guns seemed to have only just started when it had already finished, the echoes dying away in the still silent air and the smell of gunpowder clogging up their nostrils for a fleeting instant before it blew away in a little cloud of light brown smoke. Eight Urkku lay dead on the grass and the survivors from the winning group were running away across the field carrying the rabbits by the back legs so that as they ran the heads jerked crazily up and down as if they were rag dolls. They were laughing in a high-pitched, hysterical way.

The animals remained where they were for a long time, in silence. The sun beat down on their backs and the smell of burning was heavy in the air. Finally Warrigal broke the silence.

‘Most odd. Most peculiar, ’ he said. ‘Something is happening in the world of the Urkku. I’ve never seen them look or behave like that before. Beth, what do you think?’

‘I don’t know. Those men. They seemed so – I don’t know – so strange. And that fight; all that shooting. It was horrible. I don’t like it. Let’s move on quickly; get away from here.’

The girl felt a cold chill all over despite the heat of the sun. She was horribly afraid; more so than she had ever been before, and she, who had lived nearly all her life with humans, had felt it more than the animals. Something was going terribly wrong. She turned to Nab. ‘Hold me,’ she said, and he put his arms around her and she closed her eyes for a second and with her head snuggled against his shoulder she felt better.

On they walked but they could not escape the ghastly black columns of smoke nor get out of the scorched blackened landscape which seemed to stretch for mile upon mile around them in every direction. The sickly stench from the fires grew steadily more unbearable until even the act of breathing became something which they dreaded. Their hands, faces and feet were ingrained with black from the soot and the charred ground, and nowhere was there enough clean water to wash it off properly. When they came to a pond now it was almost certain to be dried up, its bed split open and cracked in great mud fissures, and they would search for a little corner somewhere where there might be a remaining puddle of foul-smelling brackish liquid with which they would attempt to slake their ravening thirst.

Every day now they saw two or three bands of Urkku like the first, wandering ragged and aimless on the burnt ground, guns under their arms and eyes constantly moving as if they were afraid of being seen. This made it harder for the animals to avoid them as they were far quieter and less easily spotted than they used to be and the travellers were only able to move slowly with Warrigal flying ahead to make sure everything was clear to go on. Often now he would come back and report Urkku in front and they would have to wait for agonizing hours until they had moved on and it was safe to go ahead. They slept during these waiting periods and travelled when they could rather than sleeping every afternoon, and they found that they made better progress after Sun-High because the heat was so intense then that there were fewer Urkku around. The sound of shooting was also common, either a single crack or a battery of shots such as they had heard that first time, and then they would come across the casualties of these random fights and be careful to avoid going too close to them for fear of disturbing the flies and because of the smell. There was very little shade from the searing heat of those afternoons because all the green foliage from the hedges and trees had been burnt off. Giant oaks and sycamores, whose leaves had once cast a fragrant cool green shade on the grass, now stood gaunt, black and naked, their charred limbs standing out starkly against the clear blue sky.

One afternoon they saw a city in the distance. No smoke came from its factory chimneys and no hum of traffic from its roads and streets. Instead it lay like a huge slumbering giant and sizzled under the heat; the sun baking the concrete and sending out dazzling reflections from the empty office block windows. A shimmering heat haze hung over it and the unearthly silence was only very occasionally shattered by the wailing of a siren.

While the animals stood on the brow of a little hill from which they could see the sprawl of concrete stretching away into the far horizon, they suddenly became aware of a column of smoke just beginning to claw its way up into the sky on their right.

‘I’ll fly over and try and see what’s happening,’ said Warrigal. ‘It’d be quicker and safer for me than any of you and I think we ought to find out.’

‘Yes, that’s a good idea. But take care,’ Nab replied. ‘We’ll wait for you back in that little hollow.’

The owl flew off slowly and quietly and the others went back down the hill. It did not take Warrigal long to come within sight of the fire and he went as close as he could, perching on the branch of one of a number of what had once been sycamores situated around the outside of a clearing. Inside the clearing a large number of Urkku were milling around and shouting and in the middle a fire was crackling and spitting fiercely. The flames were hard to see in the bright glare of the sun but he could feel its heat even from where he was perched and there was no mistaking the sickening smell of the thick black smoke as it billowed its way up from the fire. Through the smoke Wsirrigal could see two large mounds from which the Urkku kept feeding the fire but it was too thick for him to make out what they were so, very cautiously, he flew round to the other side of the clearing. The sight that met his eyes filled him with horror. The mound furthest away from him was composed of dead Urkku and the other of dead animals; but it was when he forced himself to look more closely that the full impact of what he was seeing made itself felt. Warrigal was the least emotional of any of the animals but even he was unable to contain a flood of terror as he realized that the dead animals on the second pile were all either badgers, hares, fawn-coloured dogs or owls. They had been thrown together carelessly on to the pile as if they were pieces of wood and their heads and limbs stuck out at odd angles.

Suddenly the owl’s trance-like state, caused by the horror in front of him, was shattered by a piercing shout from an Urkku who had come over to the pile to collect some more carcasses for the fire.

‘There’s one. Quick. Kill it.’ There was a roar from the other Urkku who all began to rush forward to the tree where he was perching and then the crack of a gun sounded above the noise of the fire and Warrigal heard the thud of a bullet as it hit the branch above him. He flew quickly back through the belt of trees that surrounded the clearing while behind him the mob of yelling Urkku crashed their way through the undergrowth below and the air around him hummed and whistled with the sound of bullets. Swiftly he sped through the branches, using every trick he knew to gain extra speed and keeping an eye on the ground below to lead his pursuers through the thickest undergrowth. Eventually, to his intense relief, the sounds of pursuit began to fade away into the distance and the cracking of the guns stopped. Nevertheless he did not slacken his speed until he arrived back in sight of the little hollow where the others were waiting. He did not fly straight back to them but perched for a time on a tree at the edge of the field they were in, in case he was still being followed. There was no sight of Urkku anywhere and the smoke from the fire was getting thicker so he assumed they had returned and were continuing to feed it with its grisly fuel. He put his head on one side and listened intently but, apart from the shouting in the distance, everywhere was still and quiet. Then, certain that he was not being followed, he rejoined the others.

Ever since they had heard the commotion and the shooting from the direction of the fire the others had been frantic with worry and when the owl’s familiar silhouette glided gracefully over the edge of the hollow, they were overjoyed with relief. Perryfoot jumped up and down and standing on his hind legs danced about, tapping the others with his front paws and chanting ‘Warrigal’s safe, Warrigal’s safe,’ over and over again.

The owl looked at the hare with affection and then said sadly, ‘I’m afraid I don’t bring good news. ’ Slowly he recounted every detail of what he had seen and when he had finished his tale Perryfoot was sitting slumped against the bank with his ears drooping along his back and Brock, Nab and Beth sat quietly staring at the ground. They did not understand the meaning of the dead Urkku but they slowly began to realize the awful significance of the pile of animals by the fire. Finally Warrigal spoke again.

‘Until they’re certain they have found us they will kill every badger, every owl, every hare and every dog like Sam that they can find. The longer we delay, the more will die.’

Silently they got up and climbed to the top of the hollow. The mountains, towards which they were heading and where they would find Malcoff and the mountain elves, were shimmering in the haze and appeared soft and grey in the late summer afternoon.

‘How long will it take to get there?’ Beth asked Nab.

‘I don’t know. Perhaps two days.’

They made their way, as quickly as they dared, in the direction of the mountains, but they saw nothing. No Urkku, no animals, no birds; the countryside was empty and desolate. When darkness fell they welcomed the coolness that came with the night although there was still not a breath of wind and the air was heavy and thick with heat. From the earth beneath their feet they could feel the day’s sunshine coming back up at them and their mouths became dry and parched. By Moon-High their exhausted sweating bodies were demanding a rest but in the animals’ minds was a vision of the pile of dead bodies which Warrigal had seen and it haunted them, spurring them on and on. Any delay now was unthinkable.

It was in the deepest hours of the night, between midnight and dawn, that they first heard the noise. It came from a long way behind them and at first they paid no attention to it, their minds being so intently fixed on the path ahead, but soon it grew louder and the blur of sound became distinguishable. They could make out the yelping and barking of dogs and mingled with them the shouts of the Urkku. They had all heard the sound before when Rufus and the other foxes of Silver Wood had been chased by packs of hounds and Urkku riding on horseback, whooping and cheering. But it had always been in the daytime; never at night. What were they doing out now?

They tried to ignore the noise in the hope that it would go away, and they tried also to quell the chill of fear that was fluttering in their stomachs. Dawn finally broke and a vivid gash of orange appeared over the mountains ahead of them but the barks and yelps, far from disappearing had grown louder and eventually Warrigal voiced their unspoken dread.

‘I fear we are being followed,’ he said.

‘They’re bound to find us with the dogs,’ said Perryfoot. ‘They never fail. How far behind us are they, do you think, Brock?’

‘I used to hear them starting out from the village for Silver Wood and they were louder than this so we still have some time.’

Then Nab spoke. ‘We shall have to hope that we can find Malcoff as soon as we get to the mountains. Otherwise they’ll be upon us. We must move quicker.’

Beth shrank inwardly. She was already utterly exhausted and had been hoping that they could take a little break some time soon. Now they were going to have to move faster, perhaps even to run. The sun had now appeared in the clear blue sky and it looked as if it was going to be another scorching day. She could not go on, yet if she insisted on a rest or on taking the pace more slowly she would be holding them up and once again becoming a burden to them. No; she would not give up! She would go with them until she dropped.

‘Come on, Beth. We shall have to run.’ Nab smiled down at her where she sat on the ground. Her long hair was tangled and streaked with soot from the smuts that floated everywhere and there were smudges of black on her nose and her cheeks and forehead. Her arms and legs were red and blistered from the sun and her face was flushed with the heat. She still wore her black Wellington boots but she had torn her jeans off above the knee. He thought back to the first time he had seen her, looking crisp and clean and fresh in the red gingham dress she had worn that wonderful spring afternoon down by the stream so many seasons ago. He stooped down, put both his arms around her and gently lifted her to her feet.

‘We’ll soon be safe in the mountains,’ he said. ‘Don’t worry. Everything will be all right.’

She clung on to him as if trying to draw some of his energy and strength to her own worn-out body. Then suddenly she straightened up and looking deep into his dark eyes she said, laughing, ‘Come on then, slowcoach,’ and began to trot away over the fields.

All that day they ran at a steady loping pace over the flat burnt out meadows and all that day the yelps and barks and shouts behind them grew louder and clearer. By late afternoon they had reached the foothills of the mountains. As they climbed the gradually sloping fields they noticed that the grass became greener and soon they left the charred and blackened landscape of the lowlands behind them. Mercifully also the air became cooler and a little breeze began to blow against them, lifting their hair from their faces and blowing through Brock’s and Perryfoot’s fur. The fragrance of the long summer grass and the coolness of the breeze went to their heads like wine and their spirits lifted as they ran through little green valleys and up alongside gaily tinkling streams. After the desolation they had been through everywhere seemed so fresh and the greenness all around seemed to envelop them with its lush protection so that they felt safe and comforted. The sound of the pack was muffled by the trees and when they stopped to listen it seemed as if the barking was receding into the distance so they went more slowly, often stopping to drink from one of the cool clear streams or to nibble at something tasty. It was late summer now and some of the early autumn toadstools were beginning to appear in the dark and shady places.

It was just before dawn when they emerged from the trees and valleys of the foothills into the beginning of the mountains. Before them stretched a vast sea of purple heather interspersed with clumps of cotton grass waving their white heads gently in the breeze. It wasvery hard travelling over the heather and at first they kept to the little narrow sheep tracks, but Nab was afraid that if they strayed too far from the Roosdyche they would never find it again so they had to strike up and leave the paths.

They had not travelled far when suddenly they heard the sounds of the pack again, only this time it seemed as if it was just behind them. It had emerged from the trees and, now that there was nothing to smother the noise, the closeness of their pursuers was revealed to the animals with a shock of horror. They could not see them but the frantic baying was so near that it could only be a matter of minutes before they were spotted.

Desperately they ran over the heather urging their tired worn-out bodies to go faster until the breath rasped in their throats and their legs went numb with pain. Then suddenly Beth’s knees buckled under her and she fell face down on to a large clump of heather. For a second or two, with her eyes closed, she luxuriated in the wonderful feeling of lying there and giving in to the demands of her body but then she dragged herself back to reality as she felt herself being shaken and heard Nab’s frantic voice calling to her. She looked at him and his face seemed far away. She forced herself to speak.

‘I can’t go any further. Leave me here. You go on. I’ll be all right.’ Then she closed her eyes again and a haze of swirling blackness engulfed her.