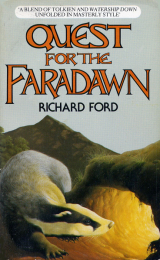

Текст книги "Quest for the Faradawn"

Автор книги: Richard Ford

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

She turned and spoke to Nab.

‘How do you feel now?’ he said.

‘A lot better,’ she answered reluctantly.

‘Well, I think we should leave in the morning. We’ll get a good night’s sleep and then leave at first light. We don’t know how far away the Urkku are and anyway I have a feeling that time is running out.’ He reached out and put his hand over hers. ‘I want to stay as well,’ he said, ‘but you know we can’t.’ He smiled at her tenderly, wishing that he could promise her that some day they would have a little home like this. ‘Perhaps…’ he started to say, but then stopped.

Beth turned back to the old couple.

‘We’ll have to go in the morning,’ she said.

‘Well, if you’re sure you’re up to it. You know best. I’ll make you some sandwiches.’

Beth laughed. ‘You’re very kind,’ she said. ‘That would be lovely.’ Now suddenly, the wine, the food and the warmth hit the exhausted bodies of Nab and Beth all at once and a great wave of tiredness engulfed them. The animals were still fast asleep around the fire and it was all Nab could do not to join them then and there, although he was unable to stifle a huge yawn.

Jim saw it and smiled. ‘You’re worn out,’ he said. ‘You must get to sleep now. We’ll be in here for a bit washing up and so on so you two had better sleep in our room at the back, where you hid this morning. We won’t disturb the animals. If they wake up we’ll see what we can find for them to eat. Otherwise we’ll leave something out.’

Wearily Nab and Beth pushed back their chairs and got up from the table. Then Beth, moved by a sudden impulse of affection, went round the table to where Ivy was sitting and, putting her arms around her neck, kissed her on the forehead.

‘Goodnight,’ she said, ‘and thank you, for a lovely day.’

Ivy looked up and her eyes were misty with tears.

‘Goodnight, dear,’ she said. ‘Sleep well.’

Then Jim got up and led them through into the bedroom. To her delight Beth saw a washbasin and towel in one corner of the room.

‘Can I have a wash?’ she said. ‘It’s a long time since I’ve used soap. Oh, and talcum powder. Do you think I could borrow some?’

‘Of course,’ Jim replied, chuckling. ‘Have a good sleep and I’ll see you in the morning. You must have some breakfast with us before you go.’

He went out and shut the door, leaving a candle on the chest of drawers next to the bed.

‘Come on,’ Beth said. ‘I’m going to teach you how to use soap and water.’

It felt strange washing in a basin instead of a stream or a pond; turning on taps for water and getting the strange foamy lather from the white block of soap. For Nab it was a series of new and exciting experiences and for Beth a poignant reminder of all that she had left behind; the smell of the soap, the feel of the towel on her face, the gurgle of the water as she pulled the plug out of the basin and the scent of the talcum powder. When she had finished washing, she went over to Ivy’s dressing table and, bracing herself, sat down on the little stool and looked in the mirror. What she saw surprised her. She had expected to be shocked and a little dismayed but instead she was strangely fascinated. Her hair hung in a great shock of curls down to her shoulders and looked fairer than she remembered it because it had been bleached by all the sun that summer, and her face was brown and weatherbeaten. But it was her eyes that really surprised her. They seemed much bigger and rounder than before and she saw in them what she had seen in Nab’s that very first time they had met, so long ago, down by the stream. They were indescribably clear and deep and she had the uncanny feeling that when she looked at them in the mirror, she was looking straight down into her own soul. But she saw more than that. Her eyes were those of a wild animal; full of energy, constantly alert, and with an innocence and purity that made them shine back at her from the mirror with such intensity that she sat riveted for so long that eventually Nab came over to her and put his face next to hers so that, to his delight, it too was reflected. They looked at their reflections in the mirror and smiled at them and then Nab pulled a funny face and Beth stuck out her tongue and they began to laugh.

There was a wooden-handled hairbrush on the dressing table top and Beth began brushing out all the tangles and curls and tousles in her hair while Nab watched entranced. It felt lovely to be using a brush again and she spent a long time running it slowly down her head from the top of the crown right down to the very ends of her hair. When she had finished she got up from the little stool and told Nab to sit on it.

‘It’s about time you had a brush through yours, ’ she said, laughing. 'You look as if you’ve been dragged through a hedge backwards.’

Nab marvelled at the confident way she handled all these hundreds of different human instruments and at all their many uses, taps, knives, forks, plates, towels, brushes: the list went on for ever and he tried to go through them all in his head while Beth brushed his hair but he soon became muddled and confused. It was all very complicated, he thought with amusement.

Finally she finished and, going over to the bed, Beth pulled back the sheets. Ivy had put them clean on that day and they were white and crisp and smelt of lavender. Slowly she got between them until, at last, she lay full length on the big soft bed and savoured to the full that delicious first moment of utter relaxation when the whole weight of her body was supported by the bed and she was able to let go of it completely. She closed her eyes and sighed; a long blissful sigh of happiness and contentment. Nab stood looking down at her. It had been a long time since they were able to relax together and he was enjoying the sight of her golden hair spread out on the white pillow and the look of perfect peace on her face.

When she opened her eyes and saw him still standing, she patted the bed beside her. ‘Come on,’ she said, ‘get in; it’s lovely.’

Carefully he copied what Beth had done and pulling back the sheets, gingerly climbed into the bed. At first as he sank into it he felt terribly unsafe and insecure as if he were lying on a bed of air and he lay tense and stiff, but after a minute or two he began to relax and by the time Beth leant over to blow the candle out he was fast asleep. She smiled to herself and gently kissed him on both his closed eyelids.

‘Goodnight, Nab,’ she said softly. ‘Sleep well,’ and, snuggling up with her arms around him, was soon lost in a deep and peaceful sleep.

CHAPTER XX

In the kitchen, Warrigal had woken up to see the dying embers of the fire casting red shadows on the inert sleeping bodies of Brock and Perryfoot and, in the middle of the room, he saw the old couple lying fast asleep on some cushions on the floor. Everything was quiet except for the sound of the wind outside and the gentle snores and heavy breathing of Brock and Jim inside. He felt refreshed and invigorated after his long sleep and decided that he would go outside to explore for a while. Luckily a window had been left open and soon the owl was out in the night, winging his way under the stars over the gorse and heather of the silent, sleeping moorland. The rain had stopped now and the smell of the damp earth filled the air, but the storm had broken the hot weather and the wind that blew down off the mountains was cool; an autumn wind, Warrigal thought, that signals the ending of summer. The sky was clear, black and infinitely deep and although there was only a tiny arc of the new moon, the stars twinkled and danced brightly.

The cool fresh night air felt wonderful to Warrigal as he glided silently, like a dark shadow, through the night. He felt happier and more contented than he had for a long, long time. Nab, Beth and the others were safely resting inside the house; tomorrow they would leave and, if luck was with them, they would very soon arrive at the home of the mountain elves and their journey would have come to its conclusion. 'What then?’ he thought. 'Where would it all end?’ and for a few moments he allowed his mind to wander back to Silver Wood and to the early days. They seemed a long way off now, almost a dream, and when a picture of the wood as they had left it at the end flashed in front of his eyes he felt a wave of bitter grief and anger well up inside so that he wrenched his mind away from those painful memories and gave himself up to the sheer joy of flying.

He dipped and dived and swooped and glided, feeling the wind rush through his feathers and clear them of all the dust and grit that they had gathered during the long dry arid days when they had been making their way across the lowlands. He was flying back along the Roosdyche they had been following the previous day when they were being pursued by the Urkku when gradually he became aware of sounds in the air. It was nothing very much at first and he dismissed it but the further he flew back down the hill the more persistent and loud did the noise become. It seemed to be coming up the hill towards him; a steady regular noise, constant with no breaks and yet punctuated by a steady relentless rhythm in the background. Warrigal felt his brief moment of optimistic confidence evaporate until it was entirely gone and he was left with the empty sick feeling of fear with which he was becoming more and more familiar.

There was a large bushy hawthorn tree on his left and he decided to perch there in the cover of the branches until he could see what was causing the noise. He made his way silently into the thickest part of the foliage and found a good spot where he could see out quite clearly through gaps in the leaves but experience told him he could not be seen. He settled down nervously to wait and then, suddenly, way down in the valley below and just beginning the long climb up on to the moors, he saw it. At first he was not quite sure what it was; it looked like an enormous caterpillar, the body of which was black but which had a bright red streak stretching all the way along its back. It wound its slow and ponderous way through the twists and turns of the foothills, weaving like a snake alongside the meanders of the stream in the valley up which it was coming.

The owl watched mesmerized as the thing came nearer and then as it left the foothills and started out on to the edge of the moors, he realized with a shudder what it was. Its body was made up of hundreds of Urkku wearing dark clothing and walking in twos and threes as if they were in a procession. Most of them were carrying flaming torches raised above their heads and it was these that had looked at a distance like the flickering red gash along the caterpillar’s back.

He shook himself free of the nausea that had gripped him and forced himself to think. They were coming up the same path that the animals had followed yesterday, and so they would probably be at the cottage in a very short while. They must leave now. Quietly he flew out of the hawthorn and, keeping low so that he was flying just above the tops of the heather and bracken, he sped back up the hill, keeping the path in sight but flying some distance away from it so that he would be less likely to be spotted. In fact he was soon out of sight of the Urkku although he could still hear the constant low murmur of their voices and the steady drum of marching feet along the ground.

Fortunately the wind was behind him and it seemed no time at all before the little cottage loomed up out of the darkness. The immense peacefulness of the scene with its quietly slumbering croft and the gentle waving of the tall grasses in the wind contrasted jarringly with the turmoil in Warrigal’s mind and he had to stop on the wall outside and gather his thoughts. It was almost as if he had dreamt the whole thing. He flew back in through the open window and inside everything was exactly as he had left it with Brock and the old man still snoring contentedly. His first task was to wake everyone, so he flew up to the top of the Welsh dresser and called loudly. There were grunts and mumbles from the sleepers and Brock turned over but no one woke up so he called again, a piercing cry so loud that the plates rattled and the window-panes vibrated. This time Brock sat bolt upright as did Perryfoot; their eyes blinking and the hackles raised on their backs. They had heard Warrigal’s first Toowitt-Toowoo through a mist of sleepy dreams about Silver Wood but the second had been full of such intensity that it had shattered the dream and left them awake and frightened. Warrigal flew down.

‘We’ve got to leave now,’ he said. ‘I’ve just been outside and seen a whole mob of Urkku coming up the hill. I’m certain they’re coming here. Come on, rouse yourselves. Ah, good, the Eldron are awake,’ he added, looking over to the cushions where Jim and Ivy were yawning and rubbing their eyes.

‘What’s to do?’ said Jim. He looked at the clock on the wall. ‘Half past three,’ he said. ‘Oh dear, what a time. Do you want to go out? I left the window open for you,’ he said, looking at Warrigal, ‘but we couldn’t leave the door open for you, Brock.’

Warrigal had flown over the windowsill and kept looking at Jim and then outside in an attempt to explain to the old man the danger that was coming up the hill.

‘Let’s have a light on,’ said Ivy, and she found the box of matches which she had left by the bed on the floor and lit a candle.

‘I think he’s trying to tell us something, ’ she said, seeing the owl on the sill. ‘We’ll have to wake up Nab and Beth.’

There was no need, for just then the bedroom door opened and they came in.

‘Warrigal,’ said Beth. ‘Was that you? What is it?’

Quickly the owl described what he had seen. When he had finished Beth repeated it to the old couple.

‘You must go now,’ said Jim. ‘It seems they know you’re here. I think perhaps they knew all along; I thought my story was accepted a bit too easily. They just wanted time to organize themselves.’

‘You must come with us then,’ said Beth. ‘If they know you’ve hidden us you’ll be in some danger, won’t you?’

Jim laughed. ‘Don’t worry about us,' he said, ‘but thank you. Now listen; there are things you ought to know about what’s been going on since you left home, Beth. You’ll have to tell Nab in his language, when you’ve both gone. There’s a lot that’s been happening that folk like Ivy and me don’t really understand so I can only tell you what we know and what we’ve heard in the village and so on. Anyway, it seems that our world, the human world, Beth, is about to collapse. The countries are all at war with one another and no one trusts anyone else. Everything is in short supply so they’re all fighting for what little is left. The rivers are dirty and stagnant, fish are dying in the sea and the crops won’t grow. It’s every man for himself, Beth. Even the police have long since stopped being able to control things; in fact they hardly even exist any more and the ones there are, are worse than useless. We’re quite lucky up here because we can grow most of what we need and we keep out of the way but it’s been terrible in the towns. And then, to make everything worse, about six months ago a terrible disease began to spread throughout the world. It started here, so they say, and was carried overseas so that now it’s everywhere. Thousands have died and those that are left scrabble over what little there is. How it started no one really knows but the rumour, and the story which the authorities put out, is that it came from you, the five of you, and that it is you who are spreading it around the country. That’s why they’re after you. There’ve been patrols out everywhere looking, spurred on by fanatical leaders who have been killing all the animals like you that they’ve seen in the hope that in the end they’ll get you. They’ve burnt great areas of the countryside in the hope of containing the disease, and the bodies of those who’ve died along with those of the animals they’ve killed, are burnt to try and stop it spreading. Fire, they think, kills the germs, and in any case nobody will dig the graves. So you see there’s not only war between countries; this disease has meant that there is virtual civil war in each country as well.’

Jim stopped talking and listened. Carried on the wind they could hear, outside in the distance, the tramping of the column coming up across the moors. Beth sat silent on one of the chairs by the dining table; unable to take in or even begin to comprehend all that she had just heard. She shook with fear; suddenly the night seemed very cold and she began to shiver.

‘But you,’ she said. ‘Why did you let us in and help us if we are the carriers of this plague?’ She began to cry and she buried her face in her hands. Jim put his arm round her gently.

‘Come on, don’t cry. There are many who don’t believe it; even in these parts, that we know of, and over the whole world there must be many more. Before the disease started, they were messing around a lot, experimenting with different kinds of weapons; germ warfare and so on. We’ve always thought that something went wrong at one of the places where this research was being done but of course no one will admit it and they’ve blamed it on you. You are the scapegoats. They may not even know anything has gone wrong themselves and so they really believe you are the cause. I don’t know.’ He paused again. ‘Listen, Beth, you must all go now. While there’s still time. The place that you want, I think, is what we call Rengoll’s Tor. There’s an old legend that I heard from my grandfather that the mountain elves live there. Follow the path straight up; it cuts through a cleft between two large hills at the top and then straight ahead you’ll see, some way ahead but still easily spotted, a strange collection of large rocks leaning against one another and sticking out of the earth at odd angles. It’s on top of a large mound and to get to it, it’s about half a day’s walk through rough moorland country, but it’s quite flat so you’ve not got much more climbing to do. Come on; you must go out the back way. There’s less chance of being seen.’

‘Here,’ said Ivy, ‘take this; and think of us when you look at it.' She took off a beautiful little gold ring with a deep green stone set in the top, which Beth had noticed and admired when they had been cooking last night’s meal. ‘And here is something for the journey,’ she added, passing Nab a bag full of sandwiches and fruit. ‘I packed it last night, ready for this morning.’

They were at the back door now. Jim opened it and they felt the cold night air on their faces.

‘Are you sure you won’t come with us?’ Beth said, but they both shook their heads.

‘Don’t you worry about us,’ said Jim. ‘We’ll be all right. Now, off you go. Take care and good luck.’

Beth kissed them both goodbye sadly. Ivy gave Nab a quick hug and Jim grasped both his hands in his, in what Nab realized was a gesture of affection.

‘Goodbye. Thank you,’ said the boy and then resolutely they turned their backs on the little house where they had been so happy and started to run steadily and slowly up the path through the heather following Warrigal, Brock and Perryfoot. Beth did not dare look back, for if she had, she knew she would have burst into tears and it would have been impossible to leave. Jim and Ivy watched them go, their eyes misty and damp with emotion, and then when the darkness had swallowed them up they turned and went back in the house.

‘You know what to do?’ said Jim, for they had discussed this last night.

‘Yes,’ Ivy replied, and she started barricading all the doors and windows with furniture while Jim nailed battens of wood across them on the outside, both for extra strength and, more important, to make it appear obvious that the cottage had been barricaded.

At just about the same moment that Nab, Beth and the animals arrived at the top of the path and began making their way through the little valley between the hills that Jim had described, the Urkku reached the cottage. Because of what they saw, they assumed, as Jim and Ivy had intended, that the travellers were inside so they immediately surrounded it and began trying to bargain with Jim and Ivy to make them hand them over. It must have been at least half an hour before Jeff and the other leaders lost their patience and began more direct methods of persuasion. Hearing the bleats from the goat shed they first of all dragged Amy out and killed her and then, when Jim still refused to release his guests, they killed Jessie, only more slowly so that every whimper and cry of pain shot through Jim and Ivy like a red hot poker in their stomachs and tortured them with doubt and anguish.

When that proved no more successful, and another half-hour had been wasted, they began to break in through the doors and windows until finally, after yet more precious time, the Urkku, having smashed their way in and searched in every corner and cupboard in the house, realized that they had been tricked. Their anger was horrible, and cruel were the deaths they inflicted on the old couple and yet, even as they died, their faces were fixed with such an expression of confidence and contentment that those who killed them, and all those who witnessed their deaths, were frightened deep within at the force that could inspire such strength.

The hounds by now had picked up the scent at the back of the house and were straining at their leashes to get away up the path, barking and yelping in a bedlam of noise. Many of the Urkku, having looted the house for anything of value, were now packing hay from one of the outbuildings around the outside walls and inside in the kitchen. Then coals from the fire, still red-hot from last night, were gathered in a bucket and scattered over the hay, which flared up immediately into high crackling flames that danced and flickered against the walls in the early dawn. Soon the flames were leaping over the roof and, by the time the column of Urkku, led by the hounds, was halfway up the back slope, the little house had been almost completely consumed by the fire.