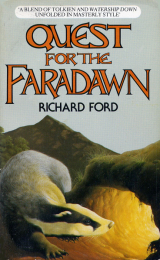

Текст книги "Quest for the Faradawn"

Автор книги: Richard Ford

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

‘Beth, Beth,’ shouted Nab but it was no use; her eyelids did not even flicker. He looked at the others; they were all stretched out panting on the heather, their bodies heaving with the effort of drawing breath. It was useless to think about going on but where could they hide? Suddenly Warrigal swooped down and landed beside him.

‘Where’ve you been? I didn’t even know you’d gone,’ said Nab.

‘I’ve been scouting around the hillside. There’s an Urkku dwelling nearby; just a little way down the hill and across. We shall have to take a chance that they are of the Eldron and will help us; I saw smoke coming out of a chimney so it is definitely occupied.’

‘We’ve got no choice, have we? We either stay here and get torn apart by the dogs for certain or else we take the risk of being handed over to them. I can carry Beth but I can’t carry these clothes as well. Brock’ll have to take them in his mouth.’

They cut off across the side of the hill with the sound of the dogs growing louder all the time. Then just below them they saw the dwelling. It was a croft. The walls were of rough white stone and they supported a roof of turf out of which grew a green haze of moss. There was a hole for a window and a hole for a door and out of the little chimney came the sweet smell of burning peat. The long low dwelling seemed to have grown out of the earth and this impression was confirmed by the heaps of peat squares piled up against the two end walls and the fact that the building itself was in a little hollow. There was a stone wall around it enclosing a garden and at the back the animals could see a small vegetable patch while at the front were a few pink and white flowers. The ground immediately outside the wall was dotted with troughs and squares from which the peat had been cut and a few sheep grazed around the outside of these while others lay inside hoping for some shade from the sun. Two white goats munched away vigorously just outside a little gate in the stone wall through which the garden was entered. There was something about the croft, and the scene below them, that was so peaceful that for a second they forgot their danger; it seemed impossible that anything bad could happen there. The place filled them with a feeling of trust and calm so that they felt no fear or doubt as they made their way down the slope. The latch on the gate made a loud click as Nab lifted it and the goats looked up and bleated, staring at them curiously for a second or two before resuming their grazing. Brock and Perryfoot walked quietly across the little garden and sat down against the wall of the croft to wait and see what happened while Warrigal flew up and perched on the roof. Still carrying Beth, Nab slowly walked up to the front door. As he got nearer he heard low voices and the clink and clatter of cups and plates. Finally he reached the door, which was open, and stood wondering what to do next. Gently he laid Beth down on the ground. What was the human word for greeting which she had taught him? Then he remembered.

‘Hello,’ he said quietly, but the sounds and voices in the kitchen carried on unchanged. They haven’t heard me, he thought, and repeated it again more loudly. This time the sounds stopped and the voices took on a different tone.

‘See who that is, Jim. I can’t think who it might be. It’s very early. Look! It’s only half past seven.’

Nab heard the sound of a chair being scraped back across the floor and then the pad of footsteps came towards the door. It was so dark inside that he could see nothing until suddenly a man stood in front of him. He was old and his hair was white and sparse but out of his wrinkled brown face shone two blue eyes that danced with light. He wore a collarless shirt with a blue pin-stripe waistcoat and on his legs a pair of baggy blue serge trousers tied around the waist by a piece of string. He stood with one hand on the door and in the other he held an old briar pipe.

‘Hello, young feller. What can I do for you? You’re a long way from the road.’ Then he spotted Beth on the grass. ‘Oh, I see. Your friend’s ill. Well, fetch her in then and we’ll see what we can do. Probably the heat.’

‘Danger. Hide,’ said Nab and lifted three fingers of one hand.

‘What? There are three more of you? What danger?’

Frantic with frustration at not being able to find the words he wanted, Nab called to the others.

‘Well, blow me down. Ivy,’ Jim called into the kitchen. ‘Here a minute!’

The owl, the badger and the hare stood in a line outside the front door while the old couple looked at them in amazement. Then Ivy spoke. She was small with grey hair and wore a navy blue dress with a faint white flowered pattern on it. When she spoke her hands shook a little with age, but her eyes, like Jim’s, were bright and merry.

‘You know who they are, don’t you, Jim?’

‘Yes.’

‘Well let’s get them inside quickly and hide them. Listen!’ She paused and waited while the barking and shouting got louder. ‘Come on, young man. Hurry up, and bring your friends in with you. Jim; put them in the bedroom.’

The old man led the animals through the front room and the kitchen until they came to an old wooden door which he opened. In the middle of the room was a large bed and around the whitewashed walls were a few pieces of furniture; an old wardrobe, a chest of drawers and a beautiful carved dressing table with photographs of Jim and of Ivy’s parents on it along with her brush and comb and one or two bottles of lavender water and scent.

‘Now, don’t worry. Get behind the bed and keep very quiet. We’ll see to them.’ He closed the door and there was silence except for muffled voices from the front room and the barking of the dogs. Nab lay Beth down gently on a piece of matting which was on the floor and sat beside her. Perryfoot and Brock squeezed under the bed and Warrigal perched on top of one of the brass bed-posts. It seemed to the animals as if they had only just settled in their places when the little house was suddenly filled with the sound of a loud thumping and banging on the door. They held their breath and their hearts quickened. It had all happened so fast that they had not had time to think whether or not they could trust the old couple; yet as soon as the seed of doubt entered their heads they dismissed it with a certainty that they could not explain. The old couple were of the Eldron; of that there could be no question. The animals had felt the goodness and warmth which flowed out towards them.

The knocking came again, only louder this time. Then a voice shouted out harshly. ‘Anyone in?’ Nab felt a tingle of fear rush up and down his spine and lodge, prickling, at the back of his neck. He instantly recognized the voice, it came to him as a terrible ghost from the past. The voice belonged unmistakably to the Urkku called Jeff; the one who, with his brother, had captured him from Silver Wood and taken him back to be locked up in the little room and, worst of all, the one who had shot Bruin. There were now voices at the door; the old man had finally answered it and his deep gentle lilting voice contrasted sharply with the jagged staccato tones of the other. ‘I must hear what they are saying,’ thought Nab, and he crawled forward very slowly and quietly until he was up against the bedroom door with his ear pressed to it. He could not understand all the words but the sense of their conversation came across to him. The old man was speaking.

‘I’m sorry I didn’t hear; I’m a bit deaf. What do you want?’

The Urkku Jeff replied harshly. ‘We’re looking for the animals. They were seen a while back; at least the owl was, and the dogs have been following them ever since. Right up here to your front door. They must have gone past. Did you not see them?’

The old man replied steadily.

‘What animals? We’ve seen nothing other than the occasional rabbit all morning.’

There was a silence which was almost menacing in its stillness. Even the dogs stopped their barking and growling.

‘Don’t play games with me, old man. You live a long way out but don’t pretend you don’t know what’s going on. If you had seen them, you would tell us, wouldn’t you?’

‘You mean the little group of animals who are rumoured to have a boy and a girl with them. The ones who are supposed to have started the plague. I have heard something of it on the wireless when they have been able to broadcast. No, I haven’t seen them. I didn’t know they were in this area.’

‘They were seen and followed here. To your house.’

‘Well, I shall look out for them; though myself, I don’t believe the stories that have been put round. There’s no proof that the plague began with them.’

Again there was a silence. When the Urkku spoke his voice was low and guttural.

‘Take care, old man. That kind of talk is dangerous. You had best forget it. Have you not had the government circulars? They must be found and destroyed, as must all their kind, for they too may be carriers and only in that way will we be sure we have got rid of it. The boy and the girl must be found and questioned as to all they know. Then they will be cleansed and educated; at least the boy will, for it appears that the girl may have led a normal life until she left her home. Apparently the disease does not affect them though they are the carriers. Now, old man; let’s not hear any more of this foolish talk. Your attitude has been noted. If you see them you will have to walk down to the village and contact the police who will inform the authorities. As you must know, very few phones are still working.’

Then the dogs began barking loudly again as the Urkku moved off down the hill. It was only when the noise had faded into the distance that the door opened and Ivy came in. ‘Well, they’ve gone for now,’ she said, half to herself and half to Nab. ‘Let’s see how your friend is, shall we?’ She knelt down beside Beth and raised her so that the girl was sitting up. She moaned and her eyelids fluttered but still she did not come round.

‘Thank you,’ Nab said and pointed outside to the door to show what he meant. Ivy looked at him and smiled gently.

‘It’s all right,’ she said. ‘Here, you hold her up while I go and get some cold water to bathe her face.’ Nab was longing to ask her and Jim what the Urkku had said exactly but his command of human language was not yet such that he could put his questions into words. He would have to wait until Beth was better.

Ivy came back with a white enamel basin full of water and began splashing the girl’s face. Perryfoot and Brock came out from under the bed and watched anxiously while Warrigal surveyed the proceedings curiously from his vantage point on the bed-post. Outside, through the window, he could see dark banks of cloud beginning to gather in the distance beyond the far peaks and he smelt rain in the air. The atmosphere was heavy and close and there was not a breath of wind.

Soon Beth was showing signs of regaining consciousness and Ivy called out, ‘Jim, bring in a cup of tea for the poor girl.’ He fetched the kettle off the range where it always sat and poured hot water from it into their little brown tea pot to warm it. Then he refilled the kettle and put it back on the hot plate to boil. The tea was in a caddy in the sideboard and as he went across to it he looked outside through the open front door and noticed that a sudden wind was getting up. ‘Storm won’t be long now,’ he muttered. ‘About time it broke. Should clear the air a bit.’ He put four spoonfuls in the pot and then called out. ‘I’ll just go and fetch the goats in, Ivy; before it rains. Kettle will have boiled when I get back.’ He went quickly out of the front gate and called the two goats over. They came running across when they heard him and he led them back through the garden to a little stone shed at one end of the house. ‘Keep your eyes off those,’ he said as the goats strayed over to the little flower bed under the wall. ‘Come on, you rascals. Let’s get you in before it rains.’ He had just put some fresh straw down ready for the coming winter and the shed smelt sweet and clean. ‘Stop chewing my trousers. Go on, get in.’ They looked at him quizzically as he began to shut the door and he laughed and gave them a friendly pat.

Great spots of rain were just beginning to fall as he went back in through the door and he heard the distant rumble of thunder. The kettle was boiling fit to burst so he quickly made the tea and took it into the bedroom. Beth was just regaining consciousness and was trying very hard to understand what they were doing in this beautiful little croft with a kindly white-haired old lady who fussed over her and now this lovely old man who had brought in a cup of tea. Tea! How she had longed for a cup of tea. Ivy poured it into a delicate little cup with a pale blue, yellow and red flower pattern on it and handed it to her. She took a sip and closed her eyes. It was like nectar. ‘It’s beautiful,’ she said, and Jim and Ivy chuckled.

‘How about your friend?’ said Jim.

‘He’s never had it before. I’m sure he’d love to try some though. Nab,’ she changed to the language of the wild, ‘try this drink. It’s a little hot but I think you’ll enjoy it. It’s very common among the Urkku and the Eldron. I used to drink it a lot. And try one of these to eat,’ she said, pointing to a plate of chocolate digestives.

Between mouthfuls of biscuit and sips of tea, Nab explained to her all that had happened since she had passed out, and told her of the way Jim had kept their presence secret to the Urkku whom he had recognized at the door. Beth was amazed. ‘Jeff Stanhope. Here. But he’s miles from his home. As we are.’ Then Warrigal spoke.

‘Remember what Saurélon said about goblins taking Urkku form. This may well be one such case. I remembered his voice as soon as he spoke.’

‘And I did,’ said Brock. ‘He killed Bruin. How could I forget?’

Jim and Ivy listened unbelievingly as the animals and the humans talked away together in this strange language.

‘I’m sure you’ve a lot to tell us,’ said Ivy, whose curiosity was growing by the second. ‘Come into the kitchen and we’ll have a good old chat. What do the animals want to eat?’

‘Well, I’m sure the badger, Brock, would love one of those biscuits if you don’t mind too much.’ Ivy nodded and Beth told Brock to try one. The badger was delighted, and wolfed down two or three, whole, in quick succession. Perryfoot and Warrigal decided to wait until later when they would go out and forage amongst the heather and made do with a bowl of water each, which they drank greedily for they were very thirsty.

In the kitchen Jim pulled up two easy chairs for Nab and Beth; Ivy sat in her high backed chair opposite him on the other side of the range and he sat down in his old wooden rocking chair on a cushion, the cover of which had been crocheted by his mother years ago. He took out his pipe and, cutting a plug of twist, began rubbing it in between his palms. He had pulled the front of the range down and the red glow of the ashes cast shadows on the low beams of the ceiling for it had gone very dark outside now although it was only mid-morning. The rain was coming down in torrents, spattering against the window-panes and running down them, and through the window they could see the wind driving great sheets of rain across the heather-covered moors. The sky was black and occasionally they saw a flash of lightning or heard thunder rolling around high above them in the clouds. Nab felt that same secure feeling of cosiness that he remembered from the times he’d watched the rain while in the shelter of the rhododendron bush in Silver Wood. He looked all around him at the kitchen; the pictures on the walls, the stove, the pots and pans, the great dark oak chest in the comer and the carved oak dresser with plates on it. Everything fascinated him; from the taps over the sink to the brass ornaments on the mantelpiece over the range. Warrigal perched on the back of his chair looking round at everything slowly; his huge round eyes resting first on one object, then another. Perryfoot and Brock were sitting in front of the range on the maroon and black rag rug that Ivy had made three winters ago and the heat of the fire with the exhausted state of their bodies had sent them both to sleep.

Jim lit his pipe and the smoke drifted languidly up and disappeared into the room. ‘Now,’ he said to Beth. ‘Tell us your tale,’ and Beth started, from the beginning; at first telling what Nab had told her and occasionally breaking off to ask him a question and then, with more confidence, talking about the time since she had left home and joined the animals. Nab understood most of what she was saying and sometimes he broke in to add something which she had forgotten or perhaps to correct her. This happened particularly over the part where she was trying to relate what the Lord Wychnor had told them and Nab felt instinctively that it was very important to Jim and Ivy that they properly understand it. They listened intently without once interrupting and the only sounds apart from Beth’s voice were the crackling of the logs in the fire, the rain outside and the quiet popping noise Jim made with his lips as he puffed steadily on his pipe while rocking slowly to and fro in the chair.

It was halfway through the afternoon when she had finished and it was still raining. No one spoke for a long while and no questions were asked. The old couple were thinking deeply and quietly about this strange story which they had just heard while Nab and Beth stared at the dancing flames in the fire and the animals dozed. Jim and Ivy were quite startled to find that they were not really surprised by what Beth had told them. Rather they felt fulfilled and in some strange way, gratified by it in that it seemed to be the inescapable, logical conclusion to the beliefs they had held all their lives and a warm glow of satisfaction spread slowly through them. The dark sky outside was still heavy with the promise of more rain and the heather was dripping with the wet. Ivy looked across at Nab and Beth and she smiled at them with such warmth and love that Beth got up and went across to her and, kneeling down, laid her head on the old lady’s lap, the way she used to with her grandmother. Jim looked at them and saw a little tear come out of the corner of Ivy’s eye and trickle slowly down her cheek. Nab also felt the love in the old lady’s smile and for him it was a strange experience. The only ones of his own race that he had known before, apart from Beth, had been figures of fear or hatred, to be avoided and despised. He had never known any Eldron and so had not experienced the goodness and warmth they were capable of. Now here he was with two of them, in their peculiar dwelling and sitting on their seats, and yet he had rarely felt more secure and safe and contented. He looked down at the rug in front of the range and chuckled to himself. Brock was curled round in a tight little ball, snoring loudly and wheezing in his sleep while Perryfoot was sitting snuggled up against him with his eyes closed, his head down and his ears pressed flat along his back. Turning his head he looked up at Warrigal who was still perched on the back of his chair and saw that he too was sleeping; his great round eyelids closed like shutters over his eyes.

Eventually Ivy broke the silence. ‘You must be starving,’ she said, and then, after gently lifting Beth’s head off her lap, she got up and began opening drawers and getting out pots and pans.

‘Can I help?’ said Beth.

‘Well, you can peel some potatoes if you don’t mind while I get on with the beans,’ replied Ivy. ‘Would you like a glass of wine? I’m sure you would. Jim,’ she called, ‘get out the elderflower and some glasses.’

The old man got up and, opening the doors of a small oak corner cupboard, fetched four glasses and a decanter cut with pictures of barley stalks and wheat around its bowl. He poured the clear light golden wine into the glasses, took one over to Nab and then two across to Beth and Ivy where they were standing by the sink. When he had picked up his own he turned round and said, ‘Let’s drink a toast.’ They all turned to face each other and then when they had lifted their glasses and Beth had explained to Nab what to do, Jim said in a quiet steady voice, ‘Let us drink to every creature, whether human or animal, that has ever suffered at the hands of any other creature.’

They were simple words but they were all deeply affected by them and as they drank the wine and considered them they each became lost in their own thoughts. For Nab, the pain of thinking was almost too much to bear. He thought of all the animals he had seen mutilated and ripped apart because of the Urkku and then into his mind, slowly and clearly, appeared pictures of Rufus, Bruin, Tara and lastly Sam. He saw them as if they were there beside him and he felt a flood of tears begin to well up inside. But then his sorrow turned to anger and his anger into resolve and an iron certainty such as he had never felt before. He lifted his glass again and said quietly to himself:

‘For you. We shall succeed for you,’ and took another mouthful of the wine.

Jim and Ivy thought not only of all the animals they had seen abused and tortured by man but also of all the hungry and the poor and the oppressed of their own race. They thought of those who were dying of illnesses which could be cured but were not and they thought of the stupidity of war and the misery and suffering of its casualties. They thought until they could think no more and then suddenly Jim spoke and his voice trembled slightly with emotion.

‘Nab. Come and give me a hand to milk the goats and get the eggs if in.’

The boy was glad of the opportunity to break free of the cloud of depression which had filled his mind and he got up and followed Jim through the front door and into the dark wet evening.

‘Here; put this over your shoulders,’ said the old man and handed Nab a big blue tattered greatcoat. ‘And put these on your feet,’ he said, handing him a pair of wellingtons. The rain spotted against their faces as they walked along the path at the front of the house until they came to the door into the goats’ shed. Inside it was warm and smelt of hay and Jessie and Amy came rushing across and began nibbling and snuffling at Jim’s hands.

‘Give these to them,’ Jim said to Nab and handed him three thick crusts of bread. The goats immediately turned their attention to him and Nab broke the crusts up and tried to share them equally between the two as they pushed against him and jostled him in their anxiety to get more than their fair share. The bread was gone in an instant, wolfed down greedily, but still they nuzzled and pulled at the pockets of the coat which Jim usually wore.

‘Show them your hands; like this,’ he said, and opened his hands so that the palms were flat to indicate to Nab what he meant. The goats sniffed disconsolately at Nab’s empty hands and then, with a look of crushing disappointment, they turned away and went over to the buckets of bran which Jim had ready for them. As they ate, he milked them and Nab watched fascinated as the old man squeezed the frothy white liquid rhythmically out of the two teats; first one, then the other, then back to the first and so on, and the jets of milk splashed into the bucket underneath. Amy was milked first and then, as Jim moved round to Jessie, he beckoned to Nab to come over and tried to show him how to milk her. It took a little while and a lot of fumbling but eventually the boy succeeded in getting a thin stream of milk out of one of the teats into the bucket. Jim shouted ‘Hooray’ and clapped his hands in applause while Nab laughed.

The old man then took over as it would have taken too long if Nab had carried on and soon he had finished.

‘We’ll take this back to the house,’ he said, picking up the buckets of milk, ‘and then we’ll go and get the eggs in and feed the hens. Goodnight, you two,’ he said to the goats and Nab gave them a stroke and a pat but they were too concerned with finishing off the bran in the bottom of their buckets to pay much attention and they only looked up when the door closed, whereupon they gave a little bleat of farewell and carried on eating.

They dropped the milk off at the house, leaving it just inside the front door, and then, pausing only to get some corn out of a little stone lean-to, they made their way around to the back and walked over to a large hencote which nestled at the side of a stone wall. The rain was still pouring down and the high craggy mountains behind them were shrouded in low cloud. It was too wet for any of the hens to be out and as they opened the door of the shed and went in there was much squawking and fluttering.

‘They’re not used to strangers. That’s why they’re making more noise than usual,’ said Jim as he went round the boxes, carefully picking up the eggs and putting them in a little brown wicker basket which he had brought from the house. ‘Put the corn in the bucket into that trough in the middle, could you,’ he said to Nab and, as he did so, the hens all flew down off their perches around the shed and began pecking away furiously. The rain pelting down on the roof sounded very loud in contrast to the muffled quietness inside as the hens concentrated on eating and Jim looked for eggs.

‘Well,’ he said, when he had walked all round and come back to the door where Nab was standing, ‘I don’t think I’m going to find any more. They’ve done well though; we’ve got plenty. I’ll just fill up their water trough and then we’ll go.’

They walked back round the other end of the house and Nab looked at the neat little vegetable patch around which Jim had put a tall fence to keep the goats and the sheep out. It was a mass of green; the fern-like tops of the potatoes, not yet dug up for the winter, rows of broccoli and sprouts and curly kale to see them through the long cold days ahead; smaller rows of autumn and winter cabbage and then at the end the high stakes on which the runner beans climbed. Jim had taken the onions in only yesterday and they were.drying in one of the outbuildings.

When they got back in through the front door Nab took off his dripping coat and passed it to J im who shook it outside and then hung it on a peg alongside his own on the back of the door. They left their muddy wellingtons on a mat at the side.

‘You’re just in time,’ Ivy called out. ‘I’m putting the soup on the table.’

‘Come on,’ Jim said to Nab. ‘I’ll bet you’re starving.’

Four steaming bowls of vegetable soup had been laid out on the kitchen table and Beth and Ivy were just about to start. Nab sat down on the chair next to Beth and she showed him how to use a spoon to drink his soup. He remembered, with a shiver of fear, the last time he had done this, so long ago. They all laughed as the soup dripped from his spoon over the table or else dribbled down his chin but he soon learnt the knack of it and began to enjoy the delicious flavour. On a plate beside the bowl, Ivy had given him a thick slice of freshly made brown bread which was still warm and he copied the others who were breaking chunks'of it off and eating it between spoonfuls of soup. Soon he had reached the bottom of the bowl and was spooning up all the pieces of vegetable that were left; cubes of tender young carrot and potatoes and turnip, peas and beans and barley. He and Beth had another bowlful and then Ivy went over to the range and fetched out of the oven four plates, on each of which stood a golden yellow green pea omelette garnished with sprigs of parsley and tomatoes.

‘Jim,’ she said. ‘Can you get the fried potatoes and the vegetables.’ The old man got up and brought across a huge bowl full of crinkly fried potatoes and another bowl, in one half of which was a heap of french beans and in the other a little mound of green sprouting broccoli spears.

‘Help yourselves,’ said Ivy. ‘I hope I’ve done enough. Anyway, have as much as you want. I’m sure you’d like some more wine. I’ll go and get the glasses and fill them up.’

Nab found handling a knife and fork a lot more difficult than a spoon so after a few awkward attempts Ivy fetched another spoon and he used that. He savoured and enjoyed every single mouthful, as did Beth, who could never remember a meal tasting so wonderful before. Jim kept topping up their wine glasses as they became empty until by the time they had finished eating they not only felt gloriously satisfied but also rather lightheaded so that they found themselves laughing with each other and with Jim and Ivy at all sorts of little things which they found inexplicably and hilariously funny. For that short magic spell of time they forgot the horrors of the past and the frightening uncertainty of the future and were suspended in the present; totally carefree and living only for the joy and happiness of those moments of laughter.

When they’d finished the omelette they had gooseberry pie and then finally cream crackers and cheese; a lovely soft goat’s-milk cheese which Ivy had made early that morning.

‘Now, to finish off, have a piece of cake,’ she said, and although Nab and Beth were full to bursting they were unable to resist the rich dark chocolate cake that Ivy pushed towards them.

‘Just a little slice,’ said Beth. ‘We’re really only being greedy.’ ‘No. You mustn’t say that. It may be a long time before you’re able to eat properly again. This will have to last you.’

‘Well, it was delicious,’said the girl, taking a bite of the cake. How she had enjoyed the evening! She wished with all her heart that they could stay here with these two warm and gentle old people in this beautiful little house. It had been like a dream from which she never wanted to wake. She looked at Nab sitting next to her with a smile all over his face and his big dark eyes twinkling with laughter in the candlelight and knew that he too would have liked to stay. Then Jim asked the question she had been afraid to ask herself all night.

‘When will you have to be leaving, Beth? You know that you’re welcome to stay for as long as you want but we don’t want to hold you or keep you.’