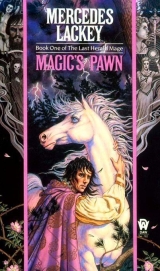

Текст книги "Magic's Pawn"

Автор книги: Mercedes Lackey

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

It was – amazing. Warm, and welcoming, paneled and furnished in goldenoak, and as well-appointed as his mother’s private chamber. Certainly nothinglike his room back at Forst Reach. A huge bed stood against one wall, a bed almost wide enough for threeand covered with a thick, soft red comforter. In the corner, a wardrobe, not a simple chest, to hold his clothing. Beside it a desk and paddedchair – Havens, an instrumentrack on the wall next to the weapons-rack! Next to the window a second, more heavily padded chair, both chairs upholstered in red that matched the comforter. His own fireplace. A small table next to the bed, and a bookcase. But that wasn’t the most amazing thing -

His room had its own private entrance, something that was either a small, glazed door or an enormous window that opened up on a garden.

Idon’t believe this,he thought, staring stupidly through the glass at the sculptured bushes and the glint of setting sun on the river beyond. I just do not believe this. I expected to be in another prison. Instead – He,tried the door Iwindow. It was unlocked, and swung open at a touch.

– instead, I’m given total freedom. I do not believe this!His knees went weak, and he had to sit down on the edge of the bed before he collapsed. The breeze that had been allowed to enter when he opened the window made the light material used as curtains flap lazily.

Gods– he thought, dazedly. Idon’t know what to think. She saves Star– then she humiliates me in front of the trainees. She gives me this room– then she tells me I’m the next thing to worthless and she threatens to beat me herself. What am I supposed to believe ?

He could hear the murmuring of voices beyond the other door, the one the tall blond had closed after himself. They sound so comfortable out there, so easy with each other,he thought wistfully. They were terribly un-alike, the three of them. The one called Donni could have been Erek’s twin sister; they looked to have been cast from the same mold – dark, curly-haired, phlegmatic. The shorter boy, Mardic, had the look of one of Withen’s smallholders; earthy, square, and brown. But the third -

Vanyel was experiencing a strange, unsteady feeling when he thought about the tall, graceful blond called Tylendel. He didn’t know why.

Not even the minstrel Shanse had evoked this depth of – disturbance – in him.

There was a burst of laughter beyond the door. They sound so happy,he thought a bit sadly, before his thoughts darkened. They’re probably laughing at me.

He clenched his teeth. Damn it, I don’t care, Iwon’t care. I don’t need their approval.

He closed his walls a little tighter about himself, and began the mundane task of settling himself into his new home. And tried not to feel himself left on the outside, telling himself over and over again that nothing mattered.

The slender girl Vanyel’s aunt had called “Donni” looked askance at all the padding and armor Vanyel picked off his armor-stand and weapons-rack. “Are you really taking all that?” she asked, hazel eyes rather wide with surprise.

He nodded shortly.

She shook her head in disbelief, her tight, sable curls scarcely moving. “I can’t see why you want all thatstuff, but I guess it’s your back. Come on.”

There’d been no one in the suite when Vanyel woke, but there hadbeen cider, bread and butter, cheese, and fruit waiting on a sideboard in the central room. He had figured that was supposed to be breakfast, seeing that someone– or several someones, more like – had already made hearty inroads on the food. He had helped himself, then found a servant to show him the way to the bathing-room and the privies, and cleaned himself up.

He’d pulled on some of his oldest and shabbiest clothing in anticipation of getting’ them well-grimed at the coming weaponry-lesson. He was back in his own room and in a very somber mood, sitting on the floor while putting some new leather lacings on his practice armor, when Donni came hunting him.

He gathered up his things and followed one step behind her out through his garden door and into the sunlit, fragrant garden, trying not to let any apprehension seep into his cool shell. She took him on a circuitous path that led from his own garden door, past several ornamental grottoes and fish ponds, down to a graveled pathway that followed the course of the river.

They trudged past what looked like a stable, except that the stalls had no doors on them, and past a smaller building beside it. Then the path took an abrupt turn to the right, ending at a gate in a high wooden fence. By now Vanyel’s arms were getting more than a little tired; he was hot, and sweating, and he hoped that this was at least close to their goal.

But no; the seemingly placid trainee flashed him what mighthave been a sympathetic grin, and opened the gate, motioning for Vanyel to go through.

“There,” she said, pointing across what seemed to be an expanse of carefully manicured lawn as wide as the legended Dhorisha Plains. At the other end of the lawn was a plain, rawly new wooden building with high clerestory windows.

“That’s the salle,” she told him. “That’s where we’re going. They just built it last year so that we could practice year ‘round.” She giggled. “I think they got tired of the trainees having bouts in the hallways when it rained or snowed!”

Vanyel just nodded, determined to show no symptoms of his weariness. She set off across the grass with a stride so brisk he had to really push himself to keep up with her. It was all he could do to keep from panting with effort by the time they actually reached the building, and his side was in agony when she slowed down enough to open the door for him.

Once inside he could see that the structure was one single large room, with a mirrored wall and a carefully sanded wooden floor. There were several young people out on the floor already, ranging in apparent age from as young as eleven or twelve to as old as their early twenties. Most of them were sparring -

Vanyel was too exhausted to take much notice of what they were up to, although the pair nearest him (he saw with a sinking heart) were working out in almost exactlythe weapons style Jervis used.

“This him?”

A woman with a soft, musical contralto spoke from behind them, and Vanyel turned abruptly, dropping a vambrace.

“Yes, ma’am,” Donni said, picking the bracer up before Vanyel had a chance even to flush. “Vanyel, this is Weaponsmaster Kayla. Kayla, this stuff is all his; I guess he brought it from home. I’ve got to get going, or I’ll miss my session in the Work Room.”

“Havens forfend,” Kayla said dryly. “Savil would eat me for lunch if you were late. Don’t forget you have dagger this afternoon, girl.”

Donni nodded and slipped out the door, leaving Vanyel alone with the redoubtable Weaponsmaster.

For redoubtable she was. From the crown of her head to the soles of her feet she was nothing but sinew and muscle. Her black hair, tightly braided to her head, showed not a strand of gray, despite the age revealed by the fine net of wrinkles around her eyes and mouth. Those gray-green eyes didn’t look as if they missed much.

For the rest, Kayla’s shoulders were nearly a handspan wider than his, and her wrists as thick as his ankles. Vanyel had no doubt that she could readily wield anyof the blades in the racks along the wall, even the ones as tall or taller than she. He did notparticularly want to face this woman in anysort of combat situation. She looked like she could quite handily take on Jervis andmop the floor with his ugly face.

Vanyel remained outwardly impassive, but was inwardly quaking as she in turn studied him.

“Well, young man,” she said quietly, after a moment that was far too long for his liking. “You might as well throw that stuff over in the corner over there – “ she nodded toward the far end of the salle, and a pile of discarded equipment, “ – we’ll see what we can salvage of it. Youcertainly won’t be needing it.”

Vanyel blinked at her, wondering if he’d missed something. “Why not?” he asked, just as quietly.

“Good gods, lad, that stuff’s about as suited to you as boots on a cat!” she replied, with a certain amusement. “Whoever your last master was, he was a fool to put you in thatgear. No, young man – you see Redel and Oden over there?’’

She pointed with her chin at a pair of slender, androgynous figures involved in an intricate, and possibly deadly dance with very light, slender swords.

“I’ll make Duke Oden your instructor; he’ll be pleased to have a pupil besides young Lord Redel. That’s the kind of style suited to you, so that’swhat you’ll be doing, young Vanyel,” she told him.

His heart rose to its proper place from its former position – somewhere in the vicinity of his boots.

Kayla graced him with a momentary smile. “Mind you, lad, Oden’s no light taskmaster. You’ll find you work up as healthy a sweat and collect just as many bruises as any of the hack-and-bashers. So let’s get you suited for it, eh?”

If the morning was an unexpected pleasure – and it was; for the first time in his life he received praisefor weapons work, and preened under it – the afternoon was an unalloyed disaster.

It started when he returned with equipment that weighed a third of what he’d carried over. He racked it with care he usually didn’t grant to weaponry, and sought the central room of the suite.

Someone – probably the hitherto invisible Margret – had taken away the food left on the sideboard this morning and replaced it with meat rolls, more fruit and cheese, and a bottle of light wine.

Tylendel was sprawled on the couch, a meat roll in one hand, a book in the other, a crease of concentration between his brows. He didn’t even look up as Vanyel moved hesitantly just into the common room itself.

Once again he got that strange, half-fearful, fluttery feeling in the pit of his stomach. He cleared his throat, and Tylendel jumped, dropping his book, and looking up with his eyes widened and his hair over one eye.

“Good gods, Vanyel, make some noise,next time!” he said, bending to retrieve his book from the floor. “I didn’t know there was anyone here but me! That’s lunch over there – “

He pointed with the half-eaten roll.

“Savil says to eat and get yourself cleaned up; she’s going to present you to the Queen before the noon recess. Then you’ll be able to have dinner with the Court; the rest of us get it on the fly as our schedules permit. Savil will be back in a few minutes so you’d better move.” He tilted his head to one side, just a little, and offered, “If you need any help. ...”

Vanyel stiffened; the offer hadn’t sounded at all unfriendly, but – it could be Tylendel was looking for a way to spy on him. Savil hadn’t necessarily told the truth.

– if only -

“No,” he replied curtly, “I don’t need any help.” He paused, then added for politeness’ sake, “Thank you.”

Tylendel gave him a dubious look, then shrugged and dove back into his book.

Savil wasback in moments; Vanyel had barely time to make himself presentable before she scooped him up and herded him off to the Throne Room.

The Throne Room was a great deal smaller than he had pictured; long and narrow, and rather dark. And stuffy; there were more people crammed into this room than it had ever been intended to hold. Somewhere down at the farther end of it was the Throne itself, beneath a huge blue and silver tapestry of a rampant winged horse with broken chains on its throat and legs that took up the entire wall over the Throne. Vanyel could see the tapestry, but nothing else; everyone else in the room seemed to be at least a hand taller than he was, and all he could see were heads.

The presentation itself was a severe disappointment. Vanyel waited with Savil at his side for nearly an hour while some wrangle or other involving a pair of courtiers was ironed out. Then Savil’s name was called; the two of them (Vanyel trailing in Savil’s formidable wake) were announced by a middle-aged Herald in full Court Whites. Vanyel was escorted to the foot of the Throne by that same Herald, where Queen Elspeth (a thin, dark-haired woman who was looking very tired and somewhat preoccupied) nodded to him in a friendly manner, and said about five words in greeting. He bowed and was escorted back to Savil’s side, and that was all there was to it.

Then Savil hustled him back to change outof Court garb and into ordinary daygarb for his afternoon classes. Mardic practically flew in the door from the hallway and took him in tow. They traversed a long, dark corridor leading from Savil’s quarters, out through a double door, to a much older section of the Palace. From there they exited a side door and out into more gardens – herb gardens this time, and kitchen gardens.

Mardic didn’t seem to be the talkative type, but he could certainly move. His fast walk took them past an l-shaped granite building before Vanyel had a chance to ask what it was, and up to a square fieldstone structure. “Bardic Collegium,” Mardic said shortly, pausing just long enough for a couple of youngsters who were running to get past him, then opening the black wooden door for him.

He didn’t say another word; just left him at the door of his first class before vanishing elsewhere into the building.

He was finding it hard to believe that Savil was going so far in ignoring his father’s orders as to put him in lessoningwith the Bardic students. Nevertheless, here he was.

Inside Bardic Collegium. Actually inside the building, seated in a row of chairs with three other youngsters in a small, sunny room on the first floor.

More than that, pacing back and forth as he lectured or questioned them was a real, live Bard in full Scarlets; a tall, powerful man who was probably as much at home wielding a broadsword as a lute.

At home Vanyel had always been a full step ahead of his brothers and cousins when it came to scholastics, so he began the hour with a feeling of boredom. History was the proverbial open book to him – or so he had always thought. He began the session with the rather smug feeling that he was going to dazzle his new classmates.

The other three boys looked at him curiously when he came in and sat down with them, but they didn’t say anything. One was mouse-blond, one chestnut, and one dark; all three were dressed nearly the same as Vanyel, in ordinary day-clothing of white raime shirt and tunic and breeches of soft brown or gray fabric. He couldn’t tell if they were Heraldic trainees or Bardic; they wore no uniforms the way their elders did. Not that it mattered, really, except that he would have liked to impress them with his scholarship if they wereBardic students.

The room was hardly bigger than his bedroom in Savil’s suite; but unlike the Heralds’ quarters, this building was old, worn, and a bit shabby. Vanyel had a moment to register disappointment at the scuffed floor, dusty furnishings, and fuded paint before the leonine Bard at the window-end of the room began the class.

After that, all he had a chance to feel was shock.

“Yesterday we discussed the Arvale annexation; today we’re going to cover the negotiations with Rethwellan that followed the annexation.” With those words, Bard Chadran launched into his lecture; a dissertation on the important Arvale-Zalmon negotiations in the time of King Tavist. It was fascinating. There was only one problem.

Vanyel had never even heard of the Arvale-Zalmon negotiations, and all he knew of King Tavist was that he was the son of Queen Terilee and the father of Queen Leshia; Tavist’s reign had been a quiet one, a reign devoted more to studied diplomacy than the kind of deeds that made for ballads. So when the Bard opened the floor to discussion, Vanyel had to sit there and try to look as if he understood it all, without having the faintest idea of what was going on.

He took reams of notes, of course, but without knowing why the negotiations had been so important, much less what they were about, they didn’t make a great deal of sense.

He escaped that class with the feeling that he’d only just escaped being skinned and eaten alive.

Religions was a bitbetter, though not much. He’d thought it was Religion, singular. He found out how wrong he was – again. It was, indeed, Religions in the plural sense. Since the population of Valdemar was a patchwork quilt of a dozen different peoples escaping from various unbearable situations, it was hardly surprising that each one of those peoples had their own religion. As Vanyel heard, over and over again that hour, the law of Valdemar on the subject of worship was “there is no ‘one, true way,’ “ But with a dozen or more “ways” in practice, it would have been terribly easy for a Bard – or Herald – to misstep among people strange to him. Hence this class, which was currently covering the “People of the One” who had settled about Crescent Lake.

It was something of a shock, hearing that what hispriest would have called rankest heresy was presented as just another aspect of the truth. Vanyel spent half his time feeling utterly foolish, and the other half trying to hide his reactions of surprise and disquiet.

But it was Literature – or rather, an event just before the Literature class – which truly deflated and defeated him.

He had been toying with the idea of petitioning one of the Bards to enroll him in their Collegium before he began the afternoon’s classes, but now he was doubtful of being able to survive the lessons.

Gods, I – I’m as pig-ignorant compared to these trainees as my cousins are compared to me,he thought glumly, slumping in the chair nearest the door as he and the other two with him waited for the teacher of Literature to put in her appearance. But– maybe this time. Lord of Light knows I’ve memorized every ballad I could ever get my hands on.

Then he overheard Bard Chadran talking out in the hallway with another Bard; presumably the teacher of this class. But when he heard his own name, and realized that they were talking about him,he stretched his ears without shame or hesitation to catch all that he could.

“ – so Savil wants us to take him if he’s got the makings,” Chadran was saying.

“Well, has he?” asked the second, a dark, sensuously female voice.

“Shanse’s heard him sing; says he’s got the voice and the hands for it, and I trust him on that,” said Chadran, hesitantly.

“But not the Gift?” the second persisted.

Chadran coughed. “I – didn’t hear any sign of it in class. And it’s pretty obvious he doesn’t compose, or we’d have heard about it. Shanse would have said something, or put it in his report, and he didn’t.”

“He has to have two out of three; Gift, Talent, and Creativity – you knowthat, Chadran,” said the woman. “Shanse didn’t see any signs of Gift either, did he?”

Chadran sighed. “No. Breda, when Savil asked me about this boy, I looked up Shanse’s report on the area. He didmention the boy, and he wasflattering enough about the boy’s musicality that we could get him training as a minstrel if – “

“If-”

“If he weren’t his father’s heir. But the truth is, he said the boy has a magnificent ear, and aptitude for mimicry, and the talent. But no creativity, and no Gift. And that’s not enough to enroll someone’s heir as a mere minstrel. Still – Breda, love, youlook for Gift. You’re better at seeing it than any of us. I’d really like to do Savil a favor on this one. She says the boy is set enough on music to defy a fairly formidable father – and we owe her a few.”

“I’ll try him,” said the woman, “But don’t get your hopes up. Shanse may not have the Gift himself, but he knows it when he hears it.”

Vanyel had something less than an instant to wonder what they meant by “Gift” before the woman he’d overheard entered the room. As tall as a man, thin, plain-she still had a presencethat forced Vanyel to pay utmost attention to every word she spoke, every gesture she made.

“Today we’re going to begin the ‘Windrider’ cycle,” she said, pulling a gittern around from where it hung across her back. “I’m going to begin with the very first ‘Windrider’ ballad known, and I’m going to present it the way it should be dealt with. Heard, not read. This ballad was neverdesigned to be read, and I’ll tell you the truth, the flaws present in it mostly vanish when it’s sung.”

She strummed a few chords, then launched into the opening to the “Windrider Unchained” – and he no longer wondered what the “Gift” could be.

Because she didn’t just sing– not like Vanyel would have sung, or even the minstrel (or, as he realized now, the Bard)Shanse would have. No – she made her listeners experienceevery word of the passage; to feel every emotion, to see the scene, to live the event as the originals must have lived it. When she finished, Vanyel knew he would never forget those words again.

And he knew to the depths of his soul that he would never be able to do what she had just done.

Oh, he tried; when she prompted him to sing the next Windrider ballad while she played, he gave it his best. But he could tell from the look in his fellow classmates’ eyes – interest, but notrapt fascination – that he hadn’t even managed a pale imitation.

As he sat down and she gestured to the next to take a ballad, he saw the pity in her eyes and the slight shake of her head – and knew then that sheknew he’d overheard the conversation in the hallway. That this was her way of telling him, gently, and indirectly, that his dream could not be realized.

It was the pity that hurt the most, after the realization that he did not have the proper material to be a Bard. It cut – as cruelly as any blade. All that work – all that fighting to get his hand back the way it had been – and all for nothing. He’d never even had a hope.

Vanyel threw himself onto his bed, his chest aching, his head throbbing -

I thought nothing would ever be worse than home – but at least I still had dreams. Now I don’t even have that.

The capper on the miserable day was his aunt, his competent, clever, selfless, damn-her-to-nine-hells aunt.

He flopped over onto his stomach, and fought back the sting in his eyes.

She’d pulled him aside right after dinner; “I asked the Bards to see if they could take you,” she’d said. “I’m sorry, Vanyel, but they told me you’re a very talented musician, but that’s all you’ll ever be. That’s not enough to get you into Bardic when you’re the heir to a holding.”

“But – “ he’d started to say, then clamped his mouth shut.

She gave him a sharp look. “I know how you probably feel, Vanyel, but your duty as Withen’s heir is going to have to come first. So you’d better resign yourself to the situation instead of fighting it.”

She watched him broodingly as he struggled to maintain his veneer of calm. “The gods know,” she said finally, “ Istood in your shoes, once. I wanted the Holding – but I wasn’t firstborn son. And as things turned out, I’m glad I didn’t get the Holding. If you make the best of your situation, you may find one day that you wouldn’t have had a better life if you’d chosen it yourself.”

How couldshe know?he fumed. Ihate her. So help me, I hate her. Everything she does is so damned perfect! She never says anything, but she doesn’t have to; all she has to do is give me thatlook. If I hear one more word about how I ‘m supposed tolike this trap that’s closed on me, I may go mad!

He turned over on his back, and brooded. It wasn’t even sunset – and he was stuck here with his lute staring down at him from the wall with all the broken dreams it implied.

And nothing to distract him. Or was there?

Dinner was over, but there were going to be people gathered in the Great Hall all night. And there were plenty of people his age there; young people who weren’tBard trainees, nor Herald proteges. Ordinary young people, more like normal human beings.

He forgot all his apprehensions about being thought a country bumpkin; all he could think of now was the admiration his wit and looks used to draw at the infrequent celebrations that brought the offspring of several Keeps and Holdings together. He needed a dose of that admiration, and needed its sweetness as an antidote to the bitterness of failure.

He flung himself off the bed and rummaged in his wardrobe for an appropriately impressive outfit; he settled on a smoky gray velvet as suiting his mood and his flair for the dramatic.

He planned his entrance to the Great Hall with care; waiting until one of those moments that occur at any gathering of people where everyone seems to choose the same moment to stop talking. When that moment came, he seized it; pacing gracefully into the silence as if it had been created expressly to display him.

It worked to perfection; within moments he had a little circle of courtiers of his own flocking about him, eager to impress the newcomer with their friendliness.

He basked in their attentions for nearly an hour before it began to pall.

A lanky youngster named Liers was waxing eloquent on the subject of his elder brother dealing with a set of brigands. Vanyel stifled a yawn; this was sounding exactlylike similar evenings at Forst Reach!

“So he charged straight at them – “

“Which was a damn fool thing to do if you ask me,” Vanyel said, his brows creasing.

“But – it takes a braveman – “ the young man protested weakly.

“I repeat, it was a damn fool thing to do,” Vanyel persisted. “Totally outnumbered, no notion if the party behind him was coming in time – great good gods, the rightthing to do would have been to turn tail and run! If he’d done it convincingly, he could have led them straight into the arms of his own troops! Charging off like that could have gotten him killed!”

“It worked,” Liers sulked.

“Oh, it worked all right, because nobody in his right mind would have done what he did!”

“It was the valiantthing to have done,” Liers replied, lifting his chin.

Vanyel gave up; he didn’t dare alienate these younglings. They were all he had -

“You’re right, Liers,” he said, hating the lie. “It was a valiant thing to have done.”

Liers smiled in foolish satisfaction as Vanyel made more stupid remarks; eventually Vanyel extricated himself from thatlittle knot of idlers and went looking for something more interesting.

The fools were as bad as his brother; he could not,would neverget it through their heads that there was nothing “romantic” about getting themselves hacked to bits in the name of Valdemar or a lady. That there was nothing uplifting about losing an arm or a leg or an eye. That there was nothing, nothing“glorious” about warfare.

As soon as he turned away from the male contingent, the female descended upon him in a chattering flock; flirting, coquetting, each doing her best to get Variyel’s attention settled on her.It was exactly the same playette that had been enacted over and over in his mother’s bower; there were more players, and the faces were both different and often prettier, but it was the identical seript.

Vanyel was bored.

But it was marginally better than being lectured by Savil, or longing after the Bards and the Gift he never would have.

“ – Tylendel,” said the pert little brunette at his elbow, with a sigh of disappointment.

“What about Tylendel?” Vanyel asked, his interest, for once, caught.

“Oh, Tashi is in love with Tylendel’s big brown eyes,” laughed another girl, a tall, pale-complected redhead.

“Not a chance, Tashi,” said Reva, who was flushed from a little too much wine.

She giggled. “You haven’t a chance. He’s – what’s that word Savil uses?”

“Shay’a’chern,”supplied Cress. “It’s some outland tongue.”

“What’s it mean?” Vanyel asked.

Reva giggled, and whispered, “That he doesn’t like girls. He likes boys. Lucky boys!”

“For Tylendel I’d turn into a boy!” Tashi sighed, then giggled back at her friend. “Oh. what a waste! Are you sure?”

“Sure as stars,” Reva assured her. “Only just last year he broke his heart over that bastard Nevis.”

Vanyel suppressed his natural reaction of astonishment. Didn’t – like girls. He knew at least that the youngling courtiers used “like” synonymously with “bedding.” But – didn’t “like” girls? “Liked” boys?

He’d known he’d been sheltered from some things, but he’d never even guessed about this one.

Was this why Withen –

“Nevis – wasn’t he the one who couldn’t make up his mind whichhe liked and claimed he’d been seduced every time he crawled into somebody’s bed?” Tashi asked in rapt fascination.

“The very same,” Reva told her. “I am soglad his parents called him home!”

They were off into a dissection of the perfidious Nevis then, and Vanyel lost interest. He drifted around the Great Hall, but was unable to find anything or anyone he cared to spend any time with. He drank a little more wine than he intended, but it didn’t help make the evening any livelier, and at length he gave up and went to bed.

He lay awake for a long time, skirting the edges of the thoughts he’d had earlier. From the way the girls had giggled about it, it was pretty obvious that Tylendel’s preferences were something short of “respectable.” And Withen -

Oh, he knew now what Withen would have to say about it if he knew that his son was even sharing the same quarters as Tylendel.

All those times he went after me when I was tiny, for hugging and kissing Meke. That business with Father Leren and the lecture on ‘ ‘proper masculine behavior.’’ The fit he had when Liss dressed me up in her old dresses like an overgrown doll. Oh, gods.

Suddenly the reasons behind a great many otherwise inexplicable actions on Withen’s part were coming clear.

Why he kept shoving girls at me, why he bought me that – professional. Why he kept arranging for friends of Mother’s with compliant daughters to visit. Why he hated seeing me in fancy clothing. Why some of the armsmen would go quiet when I came by– why some of the jokes would juststop. Father didn’t even want a hint of this to get to me.

He ached inside; just ached.

I’ve lost music – no; even if Tylendel is to be trusted, I can’t take the chance. Not even on– being his friend. Ifhe didn’t turn on me, which he probably would.

All that was left was the other dream – the ice-dream. The only dream that couldn’t hurt him.

* * *

The chasm wasn’t too wide to jump, but it was deep. And there was something – terrible – at the bottom of it. He didn’t know how he knew that, but he knew it was true. Behind him was nothing but the empty, wintry ice-plain. On the other side of the chasm it was springtime. He wanted to cross over, to the warmth, to listen to bird-song beneath the trees– but he was afraid to jump. It seemed to widen even as he looked at it.