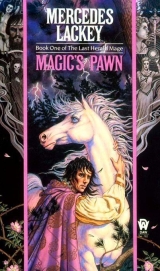

Текст книги "Magic's Pawn"

Автор книги: Mercedes Lackey

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

After all, he had nothing to lose; the worst had already occurred.

He dressed quickly; riding leathers that had originally been brown that he had ordered redyed to black – without his father’s knowledge. He was very glad that he’d done so, now. Black always made him look taller, older – and just a little bit sinister. It was a good choice for a confrontation. It was also the color of death; he wanted to remind his father of just how often the man had Vanyel – elsewhere.

He had second thoughts about his instruments, at least the lute, which he hadbeen permitted. He wouldn’t pack it, but it should behere, else Lord Withen might wonder where it was.

Besides, if he could confront Withen withit, then force the issue by packing it in front of his eyes -

It might gain him something. So he slipped quickly across to his hiding place and back before the sun actually rose, and when Withen came pounding on his door,

he was ensconced below the window with the instrument in his hands, picking out a slow, but intricate little melody. One where his right hand was doing most of the work. He had staged the entire scene with the deliberate intent to make it seem as if he had been there for hours.

Lord Withen had, no doubt, expected to find his oldest son still in his bed – had expected to rouse out a confused and profoundly unhappy boy into the thin, gray light of post-dawn. Had undoubtedly counted on rinding Vanyel as vulnerable as he had been last night.

That would have pleased you, wouldn’t it, Father – it would have given you such confirmation of my worth-lessness. . . .

Instead, he flung the door open after a single knock – to find Vanyel awake, packed, and already dressed for travel, lute suddenly stilled by his entrance.

Vanyel looked up, and regarded his father with what he hoped was a cool and distant arrogance, exactly the kind of expression one would turn upon a complete stranger who had suddenly intruded himself without invitation.

His surprise and the faint touch of unease in his eyes gave Vanyel the first feelings of gratification he’d had in a long time.

He placed his lute on the bed beside him, and stood up slowly, drawing himself up as pridefully erect as he could. “As you see, sir – “ he lifted a single finger and nodded his head very slightly in the direction of his four packs. “ – I am prepared already.”

Lord Withen was obviously taken further aback by his tone and abstracted manner. He coughed, and Vanyel realized with a sudden surge of vindictive joy that he,for once, had the advantage in a confrontation.

Then Withen flushed as Vanyel stooped quickly and caught up the neck of his lute, detuning it with swift and practiced fingers and stuffing it quickly into its traveling bag.

That was a challenge even Withen recognized. He glowered, and made as if to take the instrument from his son -

And Vanyel drew himself up to his full height. He said nothing. He only gave back Withen a stare that told him -

Push me. Do it. See what happens when you do. I have absolutely nothing to lose and I don’t care what happens to me.

Withen actually backed up a pace at the look in his son’s eyes.

“You may take your toy, but don’t think this means you can spend all your time lazing about with those worthless Bards,” Withen blustered, trying to regain the high ground he’d lost the moment he thrust the door open. “You’re going to Savil to learn something other than – “

‘ ‘I never imagined I would be able to for a moment – sir,” Vanyel interrupted, and produced a bitter not-smile. “I’m quite certain,” he continued with carefully measured venom, “that you have given my aunt very explicit instructions on the subject. And on my education. Sir.”

Withen flushed again. Vanyel felt another rush of poisonous pleasure. You know and I know what this is really about, don’t we, Father? Butyou want me to pretend it’s something else, at least in public. Too bad. I don’t intend to make this at all easy on you, and I don’t intend to be graceful in public. I have the high ground, Father. I don’t give a damn anymore, and that gives me a weapon you don’t have.

Withen made an abrupt gesture, and a pair of servants entered Vanyel’s room from the corridor beyond, each picking up two packs and scurrying out of the door as quickly as they could. Vanyel pulled the shoulder strap of the lute over his own head, arranging the instrument on his back, as a clear sign that he did not intend anyone else to be handling it.

“You needn’t see me off, sir,” he said, when Withen made no move to follow the servants with their burdens. “I’m sure you have – more important things to attend to.”

Withen winced, visibly. Vanyel strolled silently past him, then turned to deliver a parting shot, carefully calculated to hurt as much as only a truth that should not be spoken could.

“After all, sir,” he cast calmly over his shoulder, “It isn’t as if I mattered. You have four other potential – and far worthier – heirs. I amsorry you saw fit not to inform my mother of my hour of departure; it would have been pleasant to say farewell to someone who will miss my presence.”

Withen actually flinched.

Vanyel raised one eyebrow. “Don’t bother to wish me well, sir. I know what Father Leren preaches about the importance of truth, and I would not want you to perjure yourself.”

The stricken look on Withen’s face made a cold flame of embittered satisfaction spring up in Vanyel’s ice-shrouded soul. He turned on his heel and strode firmly down the corridor after the scuttling servants, not giving his father the chance to reply, nor to issue orders to the servants.

He passed the two servants with his packs in the dim, gray-lit hallway, and gestured peremptorily that they should follow him. Again, he felt that blackly bitter satisfaction; obviously Lord Withen had intended that his son should have scampered along in the servants’ wake. But the sudden reversal of roles had confused Withen and left the servants without clear instructions. Vanyel seized the unlooked-for opportunity and held to it with all his might. For once, just this once, Vanyel had gotten the upper hand in a situation, and he did not intend to relinquish it until he was forced to.

He led them down the ill-lit staircase, hearing them stumbling blindly behind him in the darkness and thankful that hewas the one carrying his lute and that there was nothing breakable in the packs. They emerged at the end of the hall nearest the kitchen; Vanyel decided to continue to force the issue by going out the servants’door to the stables. It was closer – but that wasn’t why he chose it; he chose it to make the point that he knewhis father’s thoughts about him.

The two servitors, laden as they were with the heavy packs, had to stretch to keep up with him; already they were panting with effort. As Vanyel’s boots crunched in the gravel spread across the yard between the keep and the stables, he could hear them puffing along far behind him.

The sun was barely over the horizon, and mist was rising from the meadows where the horses were turned loose during the day. It ,would likely be hot today, one of the first days of true high summer. Vanyel could see, as he came around the side of the stable, that the doors were standing wide open, and that there were several people moving about inside.

Couldn’t wait to be rid of me, could you, Father dear? Meant to hustle me off as fast as you could throw me into my clothes and my belongings into packs. I think in this I will oblige you. It should keep you sufficiently confused.

Now that he had this set of barriers, for the first time in more than a year he was able to think clearly and calmly. He was able to make plans without being locked in an emotional morass, and carry them out without losing his head to frustration. Gods, it was so simple – just don’t give a damn. Don’t care what they do to you, and they do nothing.

If I were staying, I’d never have dared to say those things. But I’m not, and by the time Father figures out how to react, I’ll be far beyond his ability to punish me. Even if he reports all this to Aunt Unsavory, it’s going to sound really stupid– and what’s more, it ‘II make him look a fool.

He paused in the open doors, feet slightly apart, hands on his hips. After a few moments, those inside noticed him and the buzz of conversation ceased altogether as they turned to gape at him in dumbfounded surprise.

“Why isn’t my mare saddled?” he asked quietly, coldly. The only two horsesbearing riding saddles were two rough cobs obviously meant for the two armsmen beside them, men who had been examining their girths and who had suddenly straightened to attention at the sound of his voice. There was another beast with a riding saddle on it, but it wasn’t a horse – it was an aging, fat pony, one every boy on the holding had long since outgrown, and a mount that was now given to Treesa’s most elderly women to ride.

“Beggin’ yer pardon, m’lord Vanyel,” said one of the grooms, hesitantly, “But yer father – “

“I really could not care less what my father ordered,”

Vanyel interrupted, rudely and angrily. “Heisn’t going to have to ride halfway to the end of the world on that hobbyhorse. Iam the one being sent on this little exile, and I am not going to ride that.I refuse to enter the capital on a beast that is going to make me look like a clown. Besides, Star is mine,not his. The Lady Treesa gave her to me,and I intend to take her with me. Saddle her.”

The groom continued to hesitate.

“If you won’t,” Vanyel said, his eyes narrowing, his voice edged with the coldest steel, “I will. Either way you’ll have trouble. And if Ihave to do it, and my lady mother finds out, you’ll have trouble from her as well as my father.”

The groom shrugged, and went after Star and her tack, leaving his fellow to strip the pony and turn it into the pasture.

Lovely. Put me on a mount only a tyro would have to ride, and make it look as if I was too much a coward to handle a real horse. Make me look a fool, riding into Haven on apony. And deprive me of something I treasured. Not this time, Father.

In fact, Vanyel was already firmly in Star’s saddle by the time Lord Withen made a somewhat belated appearance in the stableyard. The grooms were fastening the last of the packs on the backs of three mules, and the armsmen were waiting, also mounted, out in the yard.

Vanyel patted the proudly arched neck of his Star, a delicately-boned black palfrey with a perfect white star on her forehead, a star that had one long point that trailed down her nose. He ignored his father for a long moment, giving him a chance to absorb the sight of his son on his spirited little blood-mare instead of the homely old pony. Then he nudged Star toward the edge of the yard where Lord Withen stood; by his stunned expression, once again taken by surprise. She picked her way daintily across the gravel, making very little sound, like a remnant of night-shadow in the early morning light. Vanyel had had all her tack dyed the same black as his riding leathers, and was quite well aware of how striking they looked together.

So was she; she curved her neck and carried her tail like a banner as he directed her toward his father.

Lord Withen’s expression changed as they approached; first discomfited, then resigned. Vanyel kept his the same as it had been all this morning; nonexistent. He kept his gaze fixed on a point slightly above his father’s head.

Behind him, Vanyel could hear the mules being led out to have the lead rein of the first fastened to the cantle of one of the armsmen’s saddles. He halted Star about then, a few paces from the edge of the yard. He looked down at his father, keeping his face completely still, completely closed.

They stared at each other for a long moment; Vanyel could see Withen groping for something appropriate to say. And each time he began to speak, the words died unspoken beneath Vanyel’s cold and dispassionate gaze.

I’m not going to make this easy for you, Father. Not after what you ‘ve done to me; not after what you tried to do to me just now. I’m going to follow my sire’s example. I’m going to be just as nasty as you are– but I’m going to do it with more style.

The silence lengthened almost unbearably; even the armsmen began picking up the tension, and shifted uneasily in their saddles. Their cobs fidgeted and snorted restlessly.

Vanyel and Star could have been a statue of onyx and silver.

Finally Vanyel decided he had prolonged the agony enough. He nodded, once, almost imperceptibly. Then, without a word, he wheeled Star and nudged her lightly with his heels. She tossed her head and shot down the road to the village at a fast trot, leaving the armsmen cursing and kicking at their beasts behind him, trying to catch up.

He reined Star in once they were past the Forst Reach village, not wanting her to tire herself so early in the journey, and not wanting to give the armsmen an excuse to order him to ride between them.

Father’s probably told them that they ‘re to watch for me trying to bolt,he thought cynically, as Star fought the rein for a moment, then settled into a more-or-less sedate walk. And indeed, that surmise was confirmed when he saw them exchange surreptitious glances and not-too-well concealed sighs of relief. Huh. Little do they know.

For once they got beyond the Forst Reach lands that lay under the plow, they entered the completely untamed woodlands that lay between Forst Reach and the nearest eastward holding of Prytheree Ford. This forest land had been left purposely wild; there weren’t enough people to farm it at either Holding, and it supplied all of the wood products and a good half of the meat eaten in a year to the people of both Holdings.

It took skilled foresters to make their way about in a wood like this. And Vanyel knew very well that he had no more idea of how to survive in wilderland than he did of how to sprout fins and breathe water.

The road itself was hardly more than a rutted track of hard-packed dirt meandering through a tunnel of tree branches. The branches themselves were so thick overhead that they rode in a kind of green twilight. Although the sun was dispersing the mist outside the wood, there were still tendrils of it wisping between the trees and lying across the road. And only an occasional sunbeam was able to make its way down through the canopy of leaves to strike the roadway. To either side, the track was edged with thick bushes; a hint here and there of red among the green leaves told Vanyel that those bushes were blackberry hedges, probably planted to keep bears and other predators off the road itself. Even if he’d been thinking of escape, he was not fool enough to dare their brambly embrace. Even less did he wish to damage Star’s tender hide with the unkind touch of their thorns.

Beyond the bushes, so far as he could see, the forest floor was a tangle of vegetation in which hewould be lost in heartbeats.

No, he was not in the least tempted to bolt and run, but there were other reasons not to run besides the logical ones.

There were – or seemed to be – things tracking them under the shelter of the underbrush. Shadow-shapes that made no sound.

He didn’t much like those shadows behind the bushes or ghosting along with the fog. He didn’t at all care for the way they moved, sometimes following the riders on the track for furlongs before giving up and melting into deeper forest. Those shadows called to mind far too many stories and tales – and the Border, with all its uncanny creatures, wasn’t all thatfar from here.

The forest itself was too quiet for Vanyel’s taste, even had those shadows notbeen slinking beneath the trees. Only occasionally could he hear a bird call above the dull clopping of the horses’ hooves, and that was faint and far off. No breeze stirred the leaves above them; no squirrels ran along the branches to scold them. Of course it wasentirely possible that they were frightening all the nearby wildlife into silence simply with their presence; these woods werehunted regularly. That was the obvious explanation of the silence beneath the trees.

But Vanyel’s too-active imagination kept painting other, grimmer pictures of what might be lurking unseen out there.

Even though it became very warm and a halt would have been welcome, he really found himself hoping they wouldn’t.make one. The armor that had so far been proof against pressure from without cracked just a little from the pressure within of his own vivid imagination. He was uneasy when they paused to feed and water the horses and themselves at noon, and was not truly comfortable until they saddled up and moved off again. The only way he could keep his nerves in line was to concentrate on how well he had handled Lord Withen. Recalling that stupified look he’d last seen on Withen’s face gave him no end of satisfaction. Withen hadn’t seen Vanyel the boy – he’d seen a man, in some sort of control over his situation. And he plainly hadn’t enjoyed the experience.

It was with very real relief that Vanyel saw the trees break up, then open out into a huge clearing ahead of them just as the woods began to darken with the dying of the day. He was more than pleased when he saw there was an inn there, and realized that his guardians had been undoubtedly intending to stay there overnight.

They rode up the flinty dirt road to the facade of the inn, then through the entryway into the inn yard. That was where his two guardians halted, looking about for a stableboy. Vanyel dismounted, feeling very stiff, and a lot sorer than he had thought he’d be.

When a groom came to take Star’s reins, he gave them over without a murmur, then paced up and down the length of the dusty stableyard, trying to walk some feeling back into his legs. While he walked, one of the arms-men vanished into the inn itself and the other removed the packs from the mules before turning them and their cobs over to more grooms.

It was at that point that Vanyel realized that he didn’t even know his captors’ names.

That bothered him; he was going to be spending a lot of time in their company, yet they hadn’t even introduced themselves during the long ride. He was confused, and uncomfortable. Yet -

The less I feel, the better off I’ll be.

He closed his eyes and summoned his snow-field; could almost feelit chilling him, numbing him.

He began looking over the inn, ignoring the other guard, and saw with mild surprise that it was huge; much bigger than it had looked from the road. Only the front face of it was really visible when he rode up toll; now he could see the entire complex. It was easily five times the size of the little village inn at Forst Reach, and two-storied as well. Its outer walls were of stone up to the second floor, then timber; the roof was thickly thatched, and the birds Vanyel had missed in the forest all seemed to have made a happy home here, nestling into the thatch with a riot of calls and whistles as they settled in for the night. With the stables it formed two sides of a square around the stable yard, the fourth side being open on a grassy field, probably for the use of traders and their wagons. The stables were extensive, too; easily as large as Lord Withen’s, and he was a notable horsebreeder.

Blue shadows were creeping from the forest into the stableyard, although the sky above had not quite begun to darken very much. And it was getting quite chilly; something Vanyel hadn’t expected, given the heat of the day. He was just as glad when the second armsman finally put in an appearance, trailed by a couple of inn servants.

Vanyel pretended to continue to study the sky to the west, but he strained his ears as hard as he could to hear what his guardians had to say to each other.

“Any problems, Garth?” asked the one who’d remained with Vanyel, as the first bent to retrieve a pack and motioned to the servants to take the ones Vanyel recognized as being his own.

“Nay,” the first chuckled. “This early in th’ summer they be right glad of custom wi’ good coin in hand, none o’ yer shifty peddlers, neither. Just like m’lord said, got us rooms on second story wi’ his Highness there on t’ inside. No way he gets out wi’out us noticin’. Besides we bein’ second floor, Ts needful we just move t’ bed across t’ door, an’ he won’t be goin’ nowhere.”

Vanyel froze, and the little corner of him that had been wondering if he could – perhaps – make allies of these two withdrew.

So that’s why they’re keeping their distance.He straightened his back, and let that cool, expressionless mask that had served so well with his father this morning drop over his features again. Imight have guessed as much. I was a fool to think otherwise.

He turned to face his watchers. “I trust all is in order?” he asked, letting nothing show except, perhaps, boredom. “Then – shall we?” He nodded slightly toward the inn door, where a welcoming, golden light was shining.

Without waiting for a reply, he moved deliberately toward it himself, leaving them to follow.

Vanyel stared moodily at the candle at his bedside. There wasn’t anything much else to look at; hisroom had no windows. Other than that, it wasn’t that much unlike his old room back at Forst Reach; quite plain, a bit stuffy – not too bad, really. Except that it had no windows. Except for being a prison.

Inventory: one bed, one chair, one table. No fireplace, but that wasn’t a consideration given the general warmth of the building and the fact that it was summer. All four of his packs were piled over in the corner, the lute still in its case leaning up against them.

He’d asked for a bath, and they’d brought him a tub and bathwater rather than letting him go down to the bathhouse. The water was tepid, and the tub none too big – but he’d acted as if the notion had been his idea. At least his guardians hadn’t insisted on being in the same room watching him when he used it.

One of them hadescorted him to the privy and back, though; he’d headed in that direction, and the one called Garth had immediately dropped whatever it was he’d been working on and attached himself to Vanyel’s invisible wake, following about a half dozen paces behind. That had been so humiliating that he hadn’t spoken a single word to the man, simply ignored his presence entirely.

And they hadn’t consulted him on dinner either; they’d had it brought up on a tray while he was bathing.

Not that he’d been particularly hungry. He managed the bread and butter and cheese – the bread was better than he got at home – and a bit of fresh fruit. But the rest, boiled chicken, a thick gravy, and dumplings, and all of it swiftly cooling into a greasy, congealed mess on the plate, had stuck in his throat and he gave up trying to eat the tasteless stuff entirely.

But he really didn’t want to sit here staring at it, either.

So he picked up the tray, opened his door, and took it to the outer room, setting it down on a table already cluttered with oddments of traveling gear and the wherewithal to clean it.

Both men looked up at his entrance, eyes wide and startled in the candlelight. The only sound was the steady flapping of the curtains in the light breeze coming in the window, and the buzzing of a fly over one of the candles.

Vanyel straightened, licked his lips, and looked off at a point on the farther wall, between them and above their heads. “Every corridor in this building leads to the common room, so I can hardly escape you that way,” he said, in as bored and detached a tone as he could muster. “And besides, there’s grooms sleeping in the stables, and I’m certain you’ve already spoken with them.I’m scarcely going to climb out the window and run off on foot. You might as well go enjoy yourselves in the common room. You may be my jailors, but that doesn’t mean you have to endure the jail yourselves.”

With that, he turned abruptly and closed the door of his room behind him.

But he held his breath and waited right beside the door, his ear against it, the better to overhear what they were saying in the room beyond.

“Huh!” the one called Garth said, after an interval of startled silence. “Whatcha think of that?”

“That he ain’t half so scatterbrained as m’lord thinks,” the other replied thoughtfully. “Heknows damn well what’s goin’ on. Not that he ain’t about as nose-in-th’-air as I’ve ever seen, but he ain’t addlepated, not a bit of it.”

“Never saw m’lord set so on his rump before,” Garth agreed, speaking slowly.

“Ain’t never seen him taken down like that by a lord,much less a grass-green youngling. An’ never saw thatboy do anythin’ like it before, neither. Boy’s got sharp a’sudden; give ‘im that. Too sharp?’’

“Hmm..No – “ the other said. “No, I reckon in this case, he be right.” Silence for a moment, then a laugh. “Y’know, I ‘spect his Majesty just don’t want to have t’ lissen t’ us gabbin’ away at each other. Mebbe we bore ‘im, eh? What th’ hell, I could stand a beer. You?”

“Eh, if you’re buy in’, Erek – “

Their voices faded as the door to the hall beyond scraped open, then closed again.

Vanyel sighed out the breath he’d been holding in, and took the two steps he needed to reach the table, sagging down into the hard, wooden chair beside it.

Tired. Gods, I am so tired. This farce is taking more out of me than I thought it would.

He stared numbly at the candle flame, and then transferred his gaze to the bright, flickering reflections on the brown earthenware bottle beside it.

It’s aw ful wine – but it is wine. I suppose I could get good and drunk. There certainly isn’t anything else to do. At least nothing they’ll let me do. Gods, they think I’m some kind of prig. “His Majesty” indeed.

He shook his head. What’s wrong with me? Why should it matter what a couple of armsmen think about me? Why should I evenwant them on my side ? Who are they, anyway ? What consequence are they ? They ‘re just a bare step up from dirt-grubbing farmers! Why should I care what they think? Besides, they can’t affect what happens to me.

He sighed again, and tried to summon a bit more of the numbing disinterest he’d sustained himself with this whole, filthy day.

It wouldn’t come, at first. There was something in the way -

Nothing matters,he told himself sternly. Least of all what they think about you.

He closed his eyes again, and managed this time to summon a breath of the chill of his dream-sanctuary. It helped.

After a while he shifted, making the chair creak, and tried to think of something to do – maybe to put the thoughts running round his head into a set of lyrics. Instead, he found he could hear, muffled, and indistinct, the distracting sounds of the common room somewhere a floor below and several hundred feet away.

The laughter, in particular, came across clearly. Vanyel bit his lip as he tried to think of the last time he’d really laughed, and found he couldn’t remember it.

Dammit, I ambetter than they are, I don’tneed them, I don’tneed their stupid approval!He reached hastily for the bottle, poured an earthenware mug full of the thin, slightly vinegary stuff, and gulped it down. He poured a second, but left it on the table, rising instead and taking his lute from the corner. He stripped the padded bag off of it, and began retuning it before the wine had a chance to muddle him.

At least there was music. There was always music. And the attempt to get what he’d lost back again.

Before long the instrument was nicely in tune. That was one thing that minstrel – What was his name? Shanse, that was it -had praised unstintingly. Vanyel, he’d said, had a natural ear. Shanse had even put Vanyel in charge of tuning hisinstruments while he stayed at Forst Reach.

He took the lute back to the bed, and laid it carefully on the spread while he shoved the table up against the bedstead. He curled up with his back against the headboard, the bottle and mug in easy reach, and began practicing those damned finger exercises.

It might have been the wine, but his hand didn’t seem to be hurting quiteas much this time.

The bottle was half empty and his head buzzing a bit when there was a soft tap on his door.

He stopped in mid-phrase, frowning, certain he’d somehow overheard something from the next room. But the tapping came a second time, soft, but insistent, and definitely coming from his door.

He shook his head a little, hoping to clear it, and put the lute in the corner of the bed. He took a deep breath to steady his thoughts, uncurled his legs, rose, and paced (weaving only a little) to the door.

He cracked it open, more than half expecting it to be one of his captors come to tell him to shut the hell up so that they could get some sleep.

“Oh!” said the young girl who stood there, her eyes huge with, surprise; one wearing the livery of one of the inn’s servants. He had caught her with her hand raised, about to tap on the door a third time. Beyond her the armsmen’s room was mostly dark and quite empty.

“Yes?” he said, blinking his eyes, which were not focusing properly. When he’d gotten up, the wine had gone to his head with a vengeance.

“Uh – I just – “ the girl was not as young as he’d thought, but fairly pretty; soft brown eyes, curly dark hair. Rather like a shabby copy of Melenna. “Just – ye wasn’t down wi’ th’ others, m’lord, an’ I wunnered if ye needed aught?”

“No, thank you,” he replied, still trying to fathom why she was out there, trying to think through a mist of wine-fog. Unless – that armsman Garth might well have sent her, to make certain he was still where he was supposed to be.

The ties of the soft yellow blouse she was wearing had come loose, and it was slipping off one shoulder, exposing the round shoulder and a goodly expanse of the mound of one breast. She wet her lips, and edged closer until she was practically nose-to-nose with him.

“Are ye sure, m’lord?” she breathed. “Are ye sure ye cain’t think of nothin’?”

Good gods,he realized with a start, she’s trying to seduce me!

He used the ploy that had been so successful with his Mother’s ladies. He let his expression chill down to where it would leave a skin of ice OB a goblet of water. “Quite certain, thank you, mistress.”