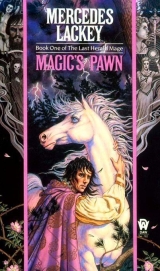

Текст книги "Magic's Pawn"

Автор книги: Mercedes Lackey

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

She looked so hopeful that Vanyel didn’t have the heart to say anything to contradict her. “Do that, Liss. I – I’ll be all right.”

She hugged him, and kissed him, and then left him.

And thenhe turned to the wall and cried. Lissa was the only support he had had. The only person who loved him without reservations. And now she was gone.

After that, he stopped even pretending to care about anything. They didn’t care enough about him to let Liss stay until he was well – so why should he care about anything or anyone, even enough to be polite?

“Armor does more than protect; it conceals. Helms hide faces – and your opponent becomes a mystery, an enigma.

Seldasen hadthat right. Just like those two down there.

The cruel, blank stares of the helm-slits gave no clues to the minds within. The two opponents drew their blades, flashed identical salutes, and retreated exactly twenty paces each to end at the opposite corners of the field. The sun was straight overhead, their shadows little more than pools at their feet. Twelve restive armored figures fidgeted together on one side of the square. The harsh sunshine bleached the short, dead grass to the color of light straw, and lit everything about the pair in pitiless detail.

Hmm. Not such enigmas once they move.

One fighter was tall, dangerously graceful, and obviously well-muscled beneath the protection of his worn padding and shabby armor. Every motion he made was precise, perilous – and professional.

The other was a head shorter. His equipment was new, the padding unfrayed, the metal lovingly burnished. But his movements were awkward, uncertain, perhaps fearful.

Still, if he feared, he didn’t lack for courage. Without waiting for his man to make a move, he shouted a tremulous defiant battle cry and charged across the sun-burnt grass toward the tall fighter. As his boots thudded on the hard, dry ground, he brought his sword around in a low-line attack.

The taller fighter didn’t even bother to move out of his way; he simply swung his scarred shield to the side. The sword crunched into the shield, then slid oif, metal screeching on metal. The tall fighter swept his shield back into guard position, and answered the blow with a return that rang true on the shield of his opponent, then rebounded, while he turned the momentum of the rebound into a cut at the smaller fighter’s head.

The pale stone of the keep echoed the sound of the exchange, a racket like a madman loose in a smithy. The smaller fighter was driven back with every blow, giving ground steadily under the hammerlike onslaught – until he finally lost his footing and fell over backward, his sword flying out of his hand.

There was a dull thudas he hit his head on the flinty, unforgiving ground.

He lay flat on his back for a moment, probably seeing stars, and scarcely moving, arms flung out on either side of him as if he meant to embrace the sun. Then he shook his head dazedly and tried to get up -

Only to find the point of his opponent’s sword at his throat.

“Yield, Boy,” rumbled a harsh voice from the shadowed mouth-slit of the helmet.

“Yield, or I run you through.”

The smaller fighter pulled off his own helm to reveal that he was Vanyel’s cousin Radevel. “If you run me through, Jervis, who’s going to polish your mail?”

The point of the sword did not waver.

“Oh, all right,” the boy said, with a rueful grin. “I yield.”

The sword, a pot-metal practice blade, went back into its plain leather sheath. Jervis pulled off his own battered helm with his shield hand, as easily as if the weight of wood and bronze wasn’t there. He shook out his sweat-dampened, blond hair and offered the boy his right, pulling him to his feet with the same studied, precise movements as he’d used when fighting.

“Next time, you yield immediately, Boy,” the armsmaster rumbled, frowning. “If your opponent’s in a hurry, he’ll take banter for refusal, and you’ll be a cold corpse.”

Jervis did not even wait to hear Radevel’s abashed assent. “You – on the end – Mekeal.” He waved to Vanyel’s brother at the side of the practice field. “Helm up.”

Vanyel snorted as Jervis jammed his own helm back on his head, and stalked back to his former position, dead center of the practice ground. “The rest of you laggards,” he growled, “let’s see some life there. Pair up and have at.”

Jervis doesn’t have pupils, he has living targets,thought Vanyel, as he watched from the window. There isn’t anyone except Father who could even give him a workout, yet he goes straight for the throat every damned time; he gets nastier every day. About all hedoes give them is that he only hits half force. Which is still enough to set Radev on his rump. Bullying bastard.

Vanyel leaned back on his dusty cushions, and forced his aching hand to run through the fingering exercise yet again. Half the lute strings plunked dully instead of ringing; both strength and agility had been lost in that hand.

I am never going to get this right again. How can I, when half the time I can’t feel what I’m doing?

He bit his lip, and looked down again, blinking at the sunlight winking off Mekeal’s helm four stories below. Every one of them will be moaning and plastering horse liniment on his bruises tonight, and boasting in the next breath about how long he lasted against Jervisthis time. Thank you, no. Not I. One broken arm was enough. I prefer to see my sixteenth birthday with therest of my bones intact.

This tiny tower room where Vanyel always hid himself when summoned to weapons practice was another legacy of Grandfather Joserlin’s crazy building spree. It was Vanyel’s favorite hiding place, and thus far, the most secure; a storage room just off the library. The only conventional access was through a tiny half-height door at the back of the library – but the room had a window – a window on the same side of the keep as the window of Vanyel’s own attic-level room.

Any time he wanted, Vanyel could climb easily out of his bedroom, edge along the slanting roof, and climb into that narrow window, even in the worst weather or the blackest night. The hard part was doing it unseen.

An odd wedge-shaped nook, this room was all that was left of the last landing of the staircase to the top floor – an obvious change in design, since the rest of the staircase had been turned into a chimney and the hole where the roof trapdoor had been now led to the chimney pot. But that meant that although there was no fireplace in the storeroom itself, the room stayed comfortably warm in the worst weather because of the chimney wall.

Not once in all the time Vanyel had taken to hiding here had anything new been added to the clutter or anything been sought for. Like many another of the old lord’s eccentricities, its inaccessibility made it easy to ignore.

Which was fine, so far as Vanyel was concerned. He had his instruments up here – two of which he wasn’t even supposed to own, the harp and the gittern – and any time he liked he could slip into the library to purloin a book.

At the point of the room he had an old chair to sprawl in, a collection of candle ends on a chest beside it so that he could read when the light was bad. His instruments were all safe from the rough hands and pranks of his brothers, and he could practice without anyone disturbing him.

He had arranged a set of old cushions by the window so that he could watch his brothers and cousins getting trounced all over the moat while he played – or tried to play. It afforded a ghost of amusement, sometimes. The gods knew he had little enough to smile about.

It was lonely – but Vanyel was always lonely, since Lissa had gone. It was bloody awkward to get to – but he couldn’t hide in his room.

Though he hadn’t found out until he’d healed up, the rest of his siblings and cousins had gone down to bachelor’s hall with Mekeal while he’d been recovering from that broken arm. He hadn’t, even when the Healer had taken the splints off.

His brothers slandered his lute playing when they’d gone, telling his father they were just as happy for Vanyel to have his own room if he wanted to stay up there. Probably Withen, recalling how near the hall was to his own quarters, had felt the same. Vanyel didn’t care; it meant that the room was his, and his alone – one scant bit of comfort.

His other place of refuge, his mother’s solar, was no longer the retreat it had been. It was too easy for him to be found there, and there were other disadvantages lately; his mother’s ladies and fosterlings had taken to flirting with him. He enjoyed that, too, up to a point – but they kept wanting to take it beyond the range of the game of courtly love to the romantic, for which he stillwasn’t ready. And Lady Treesa kept encouraging them at it.

Jervis drove Mekeal back, step by step. Fools,Vanyel thought scornfully, forcing his fingers through the exercise in time with Jervis’ blows. They must be mad, to let that sour old man make Idiots out of them, day after day– maybe break their skulls, just like he broke my arm!Anger tightened his mouth, and the memory of the shuttered satisfaction he’d seen in Jervis’ eyes the first time Vanyel had encountered him after the “accident” roiled in his stomach. Damn that bastard, hemeant to break my arm, Iknow he did; he’s good enough to judge any blow he deals to within a hair.

At least he had a secure hiding place; secure because getting into it took nerve, and neither Jervis, nor his father, nor any of the rest of them would ever have put him and a climb across the roof together in the same thought-even if they remembered the room existed.

The ill-assorted lot below didn’t look to be relatives; the Ashkevron cousins had all gone meaty when they hit adolescence; big-boned, muscled like plow horses -

– and about as dense-

– but Withen’s sons were growing straight up as well as putting on bulk.

Vanyel was the only one of the lot taking after his mother.

Withen seemed to hold thatto be his fault, too.

Vanyel snorted as Mekeal took a blow to the helm that sent him reeling backward. That one should shake up his brains! Serves him right, too, carrying on about what a great warrior he’s going to be. Clod-headed beanpole. All he can think about is hacking people to bits for the sake of ‘ ‘honor.’’

Glorious war, hah. Fool can’t see beyond the end of his nose. For all that prating, if he eversaw a battlefield he’d wet himself.

Not that Vanyelhad ever seen a real battlefield, but he was the possessor of a far more vivid imagination than anyone else in his family. He had no trouble in visualizing what those practice blades wouldbe doing if they were real. And he had no difficulty at all in imagining the “deadlie woundes” of the ballads being inflicted on hisbody.

Vanyel paid close attention to his lessons, if not to weapons work. He knew allof the history ballads and unlike the rest of his peers, he knew the parts about what happened afterthe great battles as well – the lists of the dead, the dying, the maimed. It hadn’t escaped his notice that when you added up those lists, the totals were a lot higher than the number of heroes who survived.

Vanyel knew damned well which list he’dbe on if ever came to armed conflict. He’d learned his lesson only too well: why even try?

Except that every time he turned around Lord Withen was delivering another lecture on his duty to the hold.

Gods. I’m just as much a brute beast of burden as any donkey in the stables! Duty. That’s bloody all I hear,he thought, staring out the window, but no longer seeing what lay beyond the glass. Whyme? Mekeal would be a thousand times better Lord Holder than me, and he’d justlove it! Why couldn’t I have gone with Lissa?

He sighed and put the lute aside, reaching inside his tunic for the scrap of parchment that Trevor Corey’s page had delivered to himafter he’d given Lissa’s “official” letters into Treesa’s hands.

He broke the seal on it, and smoothed out the palimpsest carefully; clever Lissa to have filched the scraped and stained piece that no one would notice was gone! She’d used a good, strong ink though; even though the letters were a bit blurred, he had no trouble reading them.

Dearest Vanyel; if only you were here! I can’t tell you how much I miss you. The Corey girls are quite sweet, but not terribly bright. A lot like the cousins, really. I know I should have written you before this, but I didn’t have much of a chance. Your arm should be better now. If only Father wasn’t so blind! What I’m learning isexactly what we were working out together.

Vanyel took a deep breath against the surge of anger at Withen’s unreasonable attitude.

But we both know how he is, so don’t argue with him, love. Just do what you ‘re told. It won’t be forever, really it won’t. Just– hold on. I’ll do what I can from this end. Lord Corey is a lot more reasonable than Father ever was and maybe I can get him talked into asking for you. Maybe that will work. Just bereally good, and maybe Father will be happy enough with you to do that. Love, Liss.

He folded the letter and tucked it away. Oh, Liss. Not a chance. Father wouldnever let me go there, not after the way I’ve been avoiding my practices. “It won’t be forever, “ hmm? I supposethat’s right. I probably won’t live past the next time Jervis manages to catch up with me. Gods. Why is it that nobody ever asks me whatI want– or when they do ask, why can’t theymean it andlisten to me?

He blinked, and looked again at the little figures below, still pounding away on each other, like so many tent pegs determined to drive each other into the ground.

He turned restlessly away from the window, stood up, and replaced the lute in the makeshift stand he’d contrived for it beside his other two instruments.

And everywhere I turn I get the same advice. From Liss– ‘ ‘don’t fight, do what Father asks.’’ From Mother-crying, vapors, and essentially the same thing. She’s not exactly stupid; if she reallycared about me, she could manage Father somehow. But she doesn’t care – not when backing me against Father is likely to cost her something. And when I tried to tell Father Leren about what Jervis wasreally like -

He shuddered. The lecture about filial duty was bad enough– but the one about “proper masculine behavior”– you’d have thought I’d been caught fornicating sheep! And all because I objected to having my bones broken. It’s like I’m doing something wrong somewhere, but no one will tell me what it is andwhy it’s wrong! I thoughtmaybe Father Leren would understand since he’s a priest, but gods, there’sno help coming from that direction.

For a moment he felt trapped up here; the secure retreat turned prison. He didn’t dare go out, or he’d be caught and forced into that despised armor – and Jervis would lay into him with a vengeful glee to make up for all the practices he’d managed to avoid. He looked wistfully beyond the practice field to the wooded land and meadows beyond. It was such a beautiful day; summer was just beginning, and the breeze blowing in his open window was heady with the aroma of the hayfields in the sun. He longed to be out walking or riding beneath those trees; he was as trapped by the things he didn’t dare do as by the ones he had to.

Tomorrow I ‘II have to go riding out with Father on his rounds,he gloomed, And no getting out ofthat. He’ll have me as soon as I come down for breakfast.

That was a new torment, added since he’d recovered. It was nearly as bad as being under Jervis’ thumb. He shuddered, thinking of all those farmers, staring, staring – like they were trying to stare into his soul. This was not going to be a pleasure jaunt, for all that he loved to ride. No, he would spend the entire day listening to his father lecture him on the duties of the Lord Holder to the tenants who farmed for him and the peasant-farmers who held their lands under his protection and governance. But that was not the worst aspect of the ordeal.

It was the people themselves; the way they measured him with their eyes, opaque eyes full of murky thoughts that he could not read. Eyes that expected everything of him; that demandedthings of him that he did not want to give, and didn’t know how to give even if he had wanted to.

Idon’twant them looking to me like that! I don’twant to be responsible for their lives!He shuddered again. Iwouldn’t know what to do in a drought or an invasion, and what’s more, I don’t care! Gods, they make my skin crawl, all those– people, eating me alive with their eyes-

He turned away from the window, and knelt beside his instruments; stretched out his hand, and touched the smooth wood, the taut strings. Oh, gods– if I weren’t me – if I could just have achance to be a Bard -

In the days before his arm had been hurt he had often imagined himself a Court Bard, not in some out-of-the-way corner like Forst Reach, but one of the Great Courts; Gyrefalcon’s Marches or Southron Keep. Or even the High Court of Valdemar at Haven. Imagined himself the center of a circle of admirers, languid ladies and jewel-bedecked lords, all of them hanging enraptured on every word of his song. He could let his imagination transport him to a different life, the life of his dreams. He could actually see himself surrounded, not by the girls of Treesa’s bower, but by the entire High Court of Valdemar, from Queen Elspeth down, until the visualization was more real than his true surroundings. He could see, hear, feel, all of them waiting in impatient anticipation for him to sing – the bright candles, the perfume, the pregnant silence –

Now even that was lost to him. Now practices were solitary, for there was no Lissa to listen to new tunes. Lissa had been a wonderful audience; she had a good ear, and knew enough about music to be trusted to tell him the truth. She had been the only person in the keep besides Treesa who didn’t seem to think there was something faintly shameful about his obsession with music. And she was the only one who knew of his dream of becoming a Bard.

There were no performances before his mother’s ladies, either, because he refused to let them hear him fumble.

And all because of the lying, bullying bastard his father had made armsmaster -

“Withen – “

He froze; startled completely out of his brooding by the sound of his mother’s breathless, slightly shrill voice just beyond the tiny door to the library. He knelt slowly and carefully, avoiding the slightest noise. The lastthing he wanted was to have his safe hiding place discovered!

“Withen, what isit you’ve dragged me up here to tell me that you couldn’t have said in my solar?” she asked. Vanyel could tell by the edge in her voice that she was ruffled and not at all pleased.

Vanyel held his breath, and heard the sound of the library door being closed, then his father’s heavy footsteps crossing the library floor.

A long, ponderous silence. Then, “I’m sending Vanyel away,” Withen said, brusquely.

“What?”Treesa shrilled. “You – how – where – why?In the gods’ names, Withen, why?”

Vanyel felt as if someone had turned his heart into stone, and his body into clay.

“I can’t do anything with the boy, Treesa, and neither can Jervis,” Withen growled. “I’m sending him to someone who can make something of him.”

“You can’t do anything because the two of you seem to think to ‘make something of him’ you have to force him to be something he can never be!” Treesa’s voice was muffled by the intervening wall, but the note of hysteria was plain all the same. “You put him out there with a man twice his weight and expect him to – “

“To behave like a man! He’s a sniveler, a whiner, Treesa. He’s more worried about damage to his pretty face and delicate little hands than damage to his honor, and you don’t help matters by making him the pet of the bower. Treesa, the boy’s become nothing more than a popinjay, a vain little peacock – and worse than that, he’s a total coward.”

“A coward!Gods, Withen – only youwould say that!” Lady Treesa’s voice was thick with scorn. “Just because he’s too clever to let that precious armsmasterof yours beat him insensible once a day!”

“So what does he do instead? Run off and hide because once – just once– he got his poor little arm broken! Great good gods, I’d broken every bone in my body at least once by the time I was his age!”

“Is that supposed to signify virtue?” she scoffed. “Or stupidity?”

Vanyel’s mouth sagged open. She’s– my gods! She’s standing up to him! I don’t believe this!

“It signifies the willingness to endure a little discomfort in order to learn,”Withen replied angrily. “Thanks to you and your fosterlings, all Vanyel’s ever learned was how to select a tunic that matches his eyes, and how to warble a love song! He’s too damned handsome for his own good – and you’ve spoiled him, Treesa; you’ve let him trade on that pretty face, get away with nonsense and arrogance you’d never have permitted in Mekeal. And now he has no sense of responsibility whatsoever, he avoids even a hint of obligation.”

“You’d prefer him to be like Mekeal, I suppose,” she replied acidly. “You’d like him to hang on your every word and never question you, never challenge you – “

“Damned right!” Withen roared in frustration. “The boy doesn’t know his damned place! Filling his head with book-learned nonsense – “

“He doesn’t know his place?Because he can think for himself? Just because he can read and write more than his bare name? Unlikecertain grown men I could name – gods, Withen, that priest of yours has you parroting every little nuance, doesn’t he? And you’re sending Van away because he doesn’t measure up to hisstandards of propriety, aren’t you? Because Vanyel has the intelligence to question what he’s told, and Leren doesn’t like questions!” Her voice reached new heights of shrillness. “That priesthas you so neatly tied around his ankle that you wouldn’t breatheunless he declared breathing was orthodox enough!”

– ah,Vanyel thought, a part of his mind still working, while the rest sat in stunned contemplation of the idea of being “sent away.” Now Treesa’s support had a rational explanation. Lady Treesa did not care for Father Leren. Vanyel was just a convenient reason to try to drive a wedge between Withen and his crony.

Although Vanyel could have told her that this was exactlythe wrong way to go about doing so.

“I expected you’d say something like that,” Withen rumbled. “You have no choice, Treesa, the boy is going, whether you like it or not. I’m sending him to Savil at the High Court. She’IIbrook no nonsense, and once he’s in surroundings where he’s not the only pretty face in the place he mightlearn to do something besides lisp a ballad and moon at himself in the mirror.”

“Savil?That old harridan?” His mother’s voice rose with each word until she was shrieking. Vanyel wanted to shriek, too.

He remembered his first – and last – encounter with his Aunt Savil only too well.

Vanyel had bowed low to the silver-haired stranger, a woman clad in impeccable Heraldic Whites, contriving his best imitation of courtly manner. Herald Savil – who had packed herself up at the age of fourteen and hied herself off to Haven without word to anyone, and then been Chosen the moment she passed the city gates – was Lissa’s idol. Lissa had pestered Grandmother Ashkevron for every tale about Savil that the old woman knew. Vanyel couldn’t understand why– but if Lissa admired this woman so much, surely there must be more to her than appeared on the surface.

It was a pity that Liss was visiting cousins the one week her idol chose to make an appearance at the familial holding.

But then again – maybe that was exactly as Withen had planned.

“So this is Vanyel,” the woman had said, dryly. “A pretty boy, Treesa. I trust he’s something more than ornamental.”

Vanyel went rigid at her words, then rose from his bow and fixed her with what he hoped was a cool, appraising stare. Gods, she lookedlike his father in the right light; like Lissa, she had that Ashkevron nose, a nose that both she and Withen thrust forward like a sharp blade to cleave all before them.

“Oh, don’t glare at me, child,” the woman said with amusement. “I’ve had better men than you try to freeze me with a look and fail.”

He flushed. She turned away from him as if he was of no interest, turning back to Vanyel’s mother, who was clutching a handkerchief at her throat. “So, Treesa, has the boy shown any sign of Gift or Talent?”

“He sings beautifully,” Treesa fluttered. “Really, he’s as good as any minstrel we’ve ever had.”

The woman turned and stared at him – stared through him. “Potential, but nothing active,” Savil said slowly. “A pity; I’d hoped at least one of your offspring would share my Gifts. You can certainly afford to spare one to the Queen’s service. But the girls don’t even have potential Gifts, your four other boys are worse than this one, and this one doesn’t appear to be much more than a clotheshorse for all his potential.”

She waved a dismissing hand at him, and Vanyel’s face had burned.

“I’ve seen what I came to see, Treesa,” she said, leading Vanyel’s mother off by the elbow. “I won’t stress your hospitality anymore.”

From all Vanyel had heard, Savil was, in many ways, not terribly unlike her brother; hard, cold, and unforgiving, preoccupied with what she perceived as her duty. She had never wedded; Vanyel was hardly surprised. He couldn’t imagine anyonewanting to bed Savil’s chill arrogance. He couldn’t imagine why warm, loving Lissa wanted to be like her.

Now his mother was weeping hysterically; his father was making no effort to calm her. By that, Vanyel knew there was no escaping the disastrous plan. Incoherent hysterics were his mother’s court of last resort; if theywere failing, there was no hope for him.

“Give it up, Treesa,” Withen said, unmoved, his voice rock-steady. “The boy goes. Tomorrow.”

“You – unfeeling monster – “That was all that was understandable through Treesa’s weeping. Vanyel heard the staccato beat of her slippers on the floor as she ran out the library door, then the slower, heavier sound of his father’s boots.

Then the sound of the door closing -

– as leaden and final as the door on a tomb.

Two

Vanyel stumbled over to his old chair and collapsed into its comfortable embrace.

He couldn’t think. Everything had gone numb. He stared blankly at the tiny rectangle of blue sky framed by the window; just sat, and stared. He wasn’t even aware of the passing of time until the sun began shining directly into his eyes.

He winced away from the light; that broke his bewildered trance, and he realized dully that the afternoon was gone – that someone would start looking for him to call him for supper soon, and he’d better be back in his room.

He slouched dispiritedly over to the window, and peered out of it, making the automatic check to see if there was anyone below who could spot him. But even as he did so it occurred to him that it hardly mattered if they found his hideaway, considering what he’d just overheard.

There was no one on the practice field now; just the empty square of turf, a chicken on the loose pecking at something in the grass. From this vantage the keep might well have been deserted.

Vanyel turned around and reached over his head, grabbing the rough stone edging the window all around the exterior, and levered himself up and out onto the sill. Once balanced there in a half crouch, he stepped down onto the ledge that ran around the edge of the roof, then reached around the gable and got a good handhold on the slates of the roof itself, and began inching over to his bedroom window.

Halfway between the two windows, he paused for a moment to look down.

It isn’t all that far– if I fell just right, the worst I’d do is break a leg– then they couldn’t send me off, could they? It might be worth it. It just might be worth it.

He thought about that – and thought about the way his broken arm had hurt -

Not a good idea; with my luck, Father would send me off as soon as I was patched up; just load me up in a wagon like a sack of grain. “Deliver to Herald Savil, no special handling. “ Or worse, I’d break my arm again, or both arms. I’ve got a chance to make that hand work again– maybe– but if I break it this time there isn’t a Healer around to make sure it’s set right.

Vanyel swung his legs into the room, balanced for a moment on the sill, then dropped onto his bed. Once there, he just lacked the spirit to even move. He slumped against the wall and stared at the sloping, whitewashed ceiling.

He tried to think if there was anything he could do to get himself out of this mess.

He couldn’t come up with a single idea that seemed at all viable. It was too late to “mend his ways” even if he wanted to.

No– no. I can’t, absolutely can’t face that sadistic bastard Jervis. Though I’m truly not sure which is the worst peril at this point in the long run, Aunt Ice-And-Iron or Jervis. Iknow what he’II do to me. I haven’t a clue to her.

He sagged, and bit his lip, trying to stay in control, trying to think logically. Allhe knew was that Savil would have the worst possible report on him; and at Haven – the irony of the name! – he would have no allies, no hiding places. That was the worst of it; going off into completely foreign territory knowingthat everybody there had been told how awful he was. That they would just be waiting for him to make a slip. All the time. But there was no getting out of it. For all that Treesa petted and cosseted him, Vanyel knew better than to rely on her for anything, or expect her to ever defyWithen. That brief flair during their argument had been the exception; Treesa’s real efforts always lay in keeping her own life comfortable and amusing. She’d cry for Vanyel, but she’d never defend him. Not like Lissa might well have –

If Lissa had been here.

When the page came around to call everyone to dinner, he managed to stir up enough energy to dust himself off and obey the summons, but he had no appetite at all.

The highborn of Forst Reach ate late, a candlemark after the servants, hirelings and the armsmen had eaten, since the Great Hall was far too small to hold everyone at once. The torches and lanterns had already been lit along the worn stone-floored corridors; they did nothing to dispel the darkness of Vanyel’s heart. He trudged along the dim corridors and down the stone stairs, ignoring the servants trotting by him on errands of their own. Since his room was at the servants’ end of the keep, he had a long way to go to get to the Great Hall.