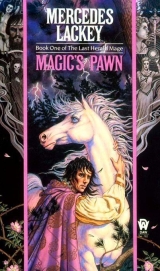

Текст книги "Magic's Pawn"

Автор книги: Mercedes Lackey

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

And with that, he jumped down from the pool ledge to the floor, and vanished again.

Twelve

“Here.” Moondance, a crease of worry between his brows, was back in a few moments with a towel and what looked like folded clothing; green, like his own. “You shall have to care for yourself, I fear. There is trouble, and I have been called to deal with it. Starwind and Savil will be with you shortly.” He hesitated a moment, visibly torn. “Forgive me, I mustgo.”

He put his burdens down on the pool edge and ran back out the doorway before Vanyel could do more than blink.

Gods– Ifeel like somebody in a tale, going to sleep and waking up a hundred years later. It seems so hard to think– like I’m still half asleep.

He dressed slowly, trying to collect his thoughts, and making heavy work of it. He didremember – vaguely – Savil telling him that he was too ill for Andrel to help; and he definitely remembered – despite the fog of drugs about the words – being told that she was going to take him to some friends of hers. He hadn’t much cared what was happening at that point. He’d either been too drugged to care, or been hurting too much.

Presumably Moondance, and the absent Starwind, were the friends she meant. They were fully as strange as those weird masks of beads and feathers that Savil had on her wall. As was this place. Wherever it was.

He pulled the deep green tunic over his head, and suddenly realized something. He wasn’t drugged – and he wasn’t hurting, either. Those places in his mind that had burned – he could still feel them, but they weren’t giving him pain.

Moondance said he Healed me. Is that why it feels like I halfway know him? Tayledras. Didn’t Aunt Savil tell us stories about them? I thought that was all those were– stories. Not real. He looked around at the strange room, half-structure, half-natural, each half fitting into the other so well he could scarcely tell where the hand of nature left off and the hand of man began. Real. Gods, if I were to describe this place, nobody would ever believe me. This– II‘ s all so different. I even feel different.

He could sense some kind of barrier around him, around his thoughts. At first it made him wary, but he tested it, tentatively, and found that it was a barrier that hecould control. When he thinned it, he became aware of presences, what must be minds, out beyond the limits of this room. Animals, surely, and birds, for their thoughts were dim and here-centered. Then two close together – very bright, but opaque and unreadable. One “felt” like Savil and the other must be the mysterious Starwind. Then two more; just as bright, just as opaque – but one he recognized by the “feel” as being Yfandes. Then a scattering of others…

Yfandes. A Companion. My Companion.

So – it was no hallucination, then. He hadsomehow gotten Herald-Gifts and a Companion.

Gifts I never wanted, at a cost I never thought I’d pay. I’d trade them and half my life to have– him– back again.

That hit like a blow to the gut. He descended from the level of the uppermost pool to the floor and sat heavily on one of the stone benches around the edge of the room, too tired and depressed to move.

Oh, ‘Lendel… gods, he thought, bleak despair overcoming him. What am I doing here? Why didn’t they just let me die?

:Do you hate me, Chosen?: said a bright, reproachful voice in his mind, :Do you hate me for wishing you to live?:

:Yfandes?: He remembered what Savil had said, about how his Companion would pine herself to death if he died, and sagged with guilt. :Oh, gods, Yfandes, no– no, I’m sorry– I just– :

He’d been able to not-think about it when he’d been drugged. He’d been able to concentrate on nothing more complicated than the next moment. Now – now his mind was only too clear. He couldn’t ignore the reality of Tylendel being gone, and there were no drugs to keep him in a vague fog of forgetting.

:You miss him.: she replied, gently. :You need him, and you miss him.:

:Like my arm. Like my heart. I just can’t imagine going on without him. I don’t know what to do with myself; where to go, what to do next.:

If Yfandes had a reply, he never heard it; just at that moment Savil and a second Tayledras, this one in white breeches, soft, low boots and jerkin, entered the room. Vanyel started to stand; Savil motioned for him to stay where he was. She and the stranger walked slowly across the stone floor and took places on the bench beside him.

Vanyel was shocked at her appearance. Although her hair had always been a pure silvery white, she’d never looked oldbefore. Now she did; she looked every year of her age and more. He recalled what Moondance had said about Tylendel’s death being as hard on her as it was on Vanyel. Now he believed it.

“Aunt Savil,” he said, hesitantly, as she and the stranger arranged themselves comfortably beside him. “Are you all right? I mean – “

“Looking particularly haglike, am I?” she asked dryly. “No, don’t bother to apologize; I’ve got a mirror. I don’t bounce back from strain the way I used to.”

He flushed, embarrassed, and feeling guilty.

“Van, this is Starwind k’Treva,” she continued. “He and Moondance are the TayledrasAdepts I told you younglings about a time or two. This,” she waved her hand around her, “is his, mostly, being as he’s k’Treva Speaker.’’

“In so much as any Tayledrascan own the land,” Star-wind noted with one raised eyebrow, his voice calling up images of ancient rocks and deep, still water. “It would be as correct, Wingsister, to say that this place owns me.”

“Point taken. This is k’Treva’s voorthayshen– that’s – how would you translate that, shayana?”

The Tayledrasat her side had a triangular face, and his long hair was arranged with two plaits at each temple, instead of one, like Moondance – and he feltolder, somehow. At least, that was how he felt to Vanyel.

“Clan Keep, I think would be closest,” Starwind said, “Although k’Treva is not a clan as your people know the meaning of the word. It is closer to the Shin’a’in notion of ‘Clan.’ “

His voice was a little deeper in pitch than Moondance’s and after a moment Vanyel recognized the “feel” of him as being the same as the “blue-green music” in his dreams.

“My lord,” Vanyel began hesitantly.

“There are no ‘lords,’ here, young Vanyel,” the Adept replied. “I speak for k’Treva, but each k’Treva rises or falls on his own.”

Vanyel nodded awkwardly. “Why am I here, sir?” he asked – then added, apprehensively, ‘ ‘What did you do to me? I – forgive me for being rude, but I knowyou did something. I feel – different.”

“You are here because you have very powerful Mage-Gifts, awakened painfully, awakened late, and out of control,” the Adept replied. His expression was calm, but grave, and held just a hint of worry. “Your aunt decided, and rightly, that there was no way in which you could be taught by the Heralds that would not pose a danger to you and those about you. Moondance and I are used to containing dangerous magics; we do this constantly, it is part of whatwe do. We can keep you contained, and Savil believes we can teach you effectively. And if we cannot teach you control, then she knows that we can and willcontain you in such a way that you will pose no danger to others.”

Moondance had not looked like this – so impersonal, so implacable. Vanyel shivered at the detached calm in Starwind’s eyes; he wasn’t certain what the Adept meant by “containing” him, but he wasn’t eager to find out.

“As to what we have done with you – Moondance Healed your channels, which are the conduits through which you direct energy. And I have taught you, a little, while you were in Healing trance. I could not teach you a great deal in trance, but what I have given you is very important, and will go a great way toward making you safe around others. I have taught you where your center is, how to ground yourself, and how to shield. So that now, at least, you are no longer out of balance, and you may guard yourself against outside thoughts and keep your own inside your mind where they belong. And there will be no more shaking of the earth because of dreams.”

So thatwas what had happened – with the music, the colors – and this new barricade around his mind.

Star wind leaned forward a little, and his expression became far more human; concerned, and earnest. “Young Vanyel, we, Moondance and I, we are perfectly pleased to have you with us, to help you. But that is allwe can do; to help you. Youmust learn control; we cannot force it upon you. Youmust learn the use of your Gifts, or most assuredly they will use you. Magic is that kind of force; I beg you to believe me, for I know this to be true. If you do not use it, it will use you. And if it begins to use you,” his eyes grew very cold, “it must be dealt with.”

Vanyel shrank back from that chill.

“But this is neither the place nor the time to speak of such things,” Starwind concluded, rising. “We have you under shield, and you are too drained to cause any problems for the nonce. Youngling, can you walk? If you can, you would do well with exercise and air, and I would take you to a vantage to show you our home, and tell you a little of what we do here.”

Vanyel nodded, not eager to be left to his aching memories again; he found on rising that he was feeling considerably stronger than he had thought. He couldn’t move very fast, but as long as Starwind and Savil stayed at a slow walk, he could keep up with them.

They went from the bathing room back through the bedroom; it looked even more like a natural grotto than the bathing room had. Vanyel almost couldn’t distinguish the real foliage from the fabric around the bed, and the “furniture,” irregularly shaped chairs, benches and tables with thick green cushions and frames of bent branches, fitted in with the plants so well as to frequently seem part of them. There was a curtained alcove (with more of those leaf-mimicking curtains) that seemed to be a wardrobe, for the curtains had been drawn back at one side enough to display a bit of clothing.

From there they passed into a third, most peculiar room. There was no furniture, and in the center of it, growing up from the stone floor, was the living trunk of a tree, one a dozen people could not have encircled with their arms. Attached to the trunk was a kind of spiral staircase. They climbed this – Vanyel feeling weak at the knees and clinging to the railing for most of the climb-to a kind of covered balcony that gave them a vantage point to see all of Starwind’s little kingdom.

This was a valley – no, a canyon;the walls were nearly perpendicular – of hot springs; Vanyel saw steam rising from the lush growth in more places than he could count. Although there was snow rimming the lip of the canyon high above, vegetation within the bowl ran riot.

“K’Treva,” Starwind said, indicating the entire valley with a wave of his hand. “Though mostly only Moondance and I dwell here-below. Beneath, the living-spaces for the hertasiand those who do not wish the trees.”

Vanyel looked over the edge of the balcony; below him was a collection of rooms, mostly windowless, but with skylights, the whole too random to be called a “house.”

“There are other living places above – which is where most of us dwell,” Starwind continued, with an ironic smile. “Moondance is not Tayledrasenough to be comfortable above the ground. The hertasiyou may or may not see; they serve us, we protect them and allow them to dwell here. They are shy of strangers – even of Tayledras;really, only Moondance is a friend to all of them. They are something like a large lizard, but they are full human in wit. If you should see one, I pray you strive not to frighten it. And although you may go where you will here-below, pray do not come here-above without invitation.”

Vanyel looked up, but couldn’t see any sign of these “living places” – only the staircase spiraling farther up the trunk and vanishing into the branches. The very thought of being up that high was dizzying, and he thought it was likely to take a great deal more than an invitation to get him to climb above.

“Tchah – I stand on Moondance’s side,” Savil replied. “I remember the first time I was here, and you made me try to sleep up in one of your perches. Never again, my friend.”

“You have no sense of adventure,” Starwind countered, putting his palms down on the rail and leaning forward a little. “The last thing, one that you may sense, so that you know it is indeed there – the barrier about the vale. It protects us from that which we would not have pass within and it keeps the vale always warm and sheltered. So – this is k’Treva. What we do here – two things. Firstly, we make places where the magic creatures of the Pelagirs may live in peace. Secondly, we take the magic out of those places where they do not live, making the land safe for man. We use the magic we take to make boundaries about the places of refuge, so that none may pass who do not belong. That is what the k’Varda, the Mage-Clans of the Tayledras, do. We guard the Pelagirs from despoilers as our cousins, the Shin’a’in, guard the Dhorisha Plains.”

“As I keep saying, you’re like we are. You guard the Pelagirs as the Heralds guard Valdemar,” Savil said.

Starwind nodded, his braids swaying. “Aye, save that your Heralds concern themselves with the people, and the Tayledraswith the land.”

“Valdemar isthe people; we could pack up and flee again, as we did at the founding, and still be Valdemar. I suspect the same would be true of you, if you’d only admit it.”

“Na, the Tayledrasare bound to the land, cannot live outside the Pelagirs; we must – “ Starwind was interrupted by the scream of a hawk somewhere above his head. He threw up his forearm, and a large, white raptor plunged down out of the canopy of leaves to land on Starwind’s arm. Vanyel winced, then saw that the Tayledraswore white leather forearm guards, which served to keep the wicked talons from his flesh.

It was a gyrefalcon; its wings beat the air for a moment before it settled, its golden eyes fixed on Starwind’s face.

The Tayledrassmoothed its head with one finger, then stared into the hawk’s eyes for a long, long time, seeming to be reading something there.

Then, without warning, he flung up his arm, launching it back into the air from his wrist. The falcon’s wings beat against the thick, damp air, then it gained height and vanished back up into the tree branches.

“Bad news?” Savil asked.

“Nay – good. The situation is not so evil as we feared. Moondance is wearied, but he shall return by sunrise.”

“I’m glad to hear something is going right for someone,” Savil replied, sighing.

“Indeed,” the Adept replied, turning those strange, unreadable eyes on Vanyel. “Indeed. Young Vanyel, I would advise you to walk about, regain your health, eat and rest. When Moondance returns and is at full strength, your schooling will begin.”

So he did as he was told to do; exploring what Starwind called “the vale” from one end to the other. It was shaped like a teardrop, and smaller than it seemed; there were so many pools and springs, waterfalls and geysers, and all cloaked in incredible greenery that effectively hid paths that came within whispering distance of each other, that it gave the illusion of being an endless wilderland.

It kept him occupied, at least. The vale was so exotic, so strange, that he could lose himself in it for hours – and forget, in watching the brightly colored birds and fish, how very much alone he was.

Half of him longed for the time – before Tylendel. The isolation of that dream-scape. The other half shrank from it. He no longer knew what he wanted, anymore, or what he was.

He certainly didn’t know what to do about Yfandes; he needed her, he loved her, but that very affection was a point of vulnerability, another place waiting to be hurt. She seemed to sense his confusion, and kept herself nearby, but not at hand, Mindspeaking only when he initiated the contact.

Savil was staying clear of him, which helped. When Moondance finally made an appearance, he made some friendly overtures, but didn’t go beyond them; Vanyel was perfectly content to leave things that way.

When he asked, the younger Tayledrasacted as a kind of guide around the vale, pointing out things Vanyel had missed, explaining how the mage-barrier kept the cold – and other things – out of the vale.

The elusive hertasinever appeared, although their handiwork was everywhere. Clothing vanished and returned cleaned and mended, food appeared at regular intervals, rooms seemed to sweep themselves.

When the vale became too familiar, Vanyel tried to catch a glimpse of them. Anything to keep from thinking.

Then he was given something else to think about.

:You fail,: Starwind said in clear Mindspeech. He was seated cross-legged on the rock of the floor beyond the glowing blue-green barrier, imperturbable as a glacier. -.Again, youngling.:

:But– : Vanyel protested from the midst of the barrier-circle the Adept had cast around him, . I– : He was having a hard time shaping his thoughts into Mindspeech.

:You,: Starwind nodded. .-Exactly so. Only you. Until you match your barrier and merge it with mine, mine will remain. And while mine remains, you cannot pass it, and I will not take you from this room.:

Vanyel drooped with weariness; it seemed that the Tayledrasmage had been schooling him, without pause or pity, for days, not mere hours. This was the seventh – or was it eighth? – such test the Adept had put him to. Starwind would go intohis head, somehow, show him what was to be done. Once. Then Vanyel fumbled his way through whatever it was. As quickly as Vanyel mastered something, the Adept sprang a trial of it on him.

There was no sign of exit or entrance in this barren, rock-walled room where he’d been taken, and no clue as to where in the complex of ground-level rooms it was. There was only Starwind, his pointed face as expressionless as the rock walls.

Vanyel didn’t know what to think anymore. These new senses of his – they told him things he wasn’t sure he wanted to know. For instance – there was something in this valley. A power – a living power. It throbbed in his mind, in time with his own pulse. He had told Savil, thinking he must be ill and imagining it. She had just nodded and told him not to worry about it.

He hadn’t asked her much, or gone to her often. If I don’t touch, I can’t be hurt again. The half-unconscious litany was the same, but the meaning was different. I’II don’t open myself, I won’t be open to loss either.

The Tayledras, Starwind and Moondance, alternately frightened and fascinated him. They were like no one he’d ever known before, and he couldn’t read them. Starwind in particular was an enigma. Moondance seemed easier to reach.

But there was always that danger. Don’t reach; don’t touch, whispered the part of him that still hurt. Don’t try.

There had been a point back at Haven when he’d tried to reach out, first to Savil, then to Lissa. He’d wanted someone to depend on, to tell him what to do, but the moment he’d tried to get them to make his decisions for him, they’d pushed him gently away.

Now – no more; all he wanted was to be left alone.

It seemed, however, that the Tayledrashad other plans.

Savil had come to get him in the morning, after several days of wandering about on his own, reminding him of what Starwind had said about being schooled in controlling these unwanted powers of his. He’d followed her through three or four rooms he hadn’t seen before into -

– something -

He wasn’t sure what it was; it had felt a little like a Gate, but there was no portal, just a spot marked on the floor. He’d stumbled across it, whatever it was, and found himself on the floor of this room, a room with no doorways.

Savil had appeared behind him, but before he could say anything, she’d just given him a troubled look, said to Starwind, “Don’t hurt him, shayana,”and left. Stepped into thin air and was gone. Left him alone with this – this madman. This unpredictable creature who’d been forcing him all morning to do things he didn’t understand, using the powers he hadn’t even come to terms with possessing, much less comprehending.

“Why are you doing this to me?” he cried, ready to weep with weariness. Starwind ignored the words as if they had never been spoken.

:Mindspeech, Chosen,: came Yfandes’ calm thought, -.That is part of his testing. Use Mindspeech.:

He braced himself, sharpened his thoughts into a kind of dagger, and flungthem at Starwind’s mind.

:Why are you DOING this to me?:

.-Gently,: came the unruffled reply. .-Gently, or I shall not answer you.:

Well, that was more than he’d gotten out of the Adept in hours. :Why?: he pleaded.

:You are a heap of dry tinder,: Starwind replied serenely. :You are a danger to yourself and those around you. It requires only a spark to send you into an uncontrolled blaze. I teach you control, so that the fires in you come when you will and where you will.: He stared at Vanyel across the shimmering mage-barrier. : Would you havethis again?:

He flung into Vanyel’s face memories that could only have come from Savil – a clutch of Herald-trainees weeping hysterically, infected with hisgrief; Mardic flying through the air, hitting the wall, and sliding down it to land in an unconscious heap; the very foundations of the Palace shaking -

:No– : he shuddered.

.-There could be worse– : Starwind showed him what he meant by “worse.” A vivid picture of Withen dead – crushed like a beetle beneath a boot – by the powers Vanyel did not yet comprehend and could not direct.

:NO!: He tried to deny the very possibility that he could do anything of the kind, rejecting the image with a violence that -

– that made the floor beneath him tremble.

.-You see?: Starwind said, still unperturbed. :You see? Without control, without understanding, you can– and will– kill, without ever meaning to. Now– :

Vanyel hung his head, and wearily tried to match the barrier one more time.

Savil ran for the pass-through, in response to Starwind’s urgent summons, Moondance a bare pace behind her. She hit the permanent set-spell, a kind of low-power Gate, at a run; there was the usual eyeblink of vertigo, and she stumbled onto the slate floor of Starwind’s Work Room and right into the middle of a royal mess.

Starwind was only now picking himself up off the floor behind her; there was a smell of scorched rock and the acrid taint of ozone in the air. And small wonder; the area around all around Vanyel in the center of the Work Room was burned black.

Lying sprawled at one side of the burned area was the boy himself, scorched and unconscious.

Moondance popped through the pass-through, glanced from one fallen body to the other, and made for the boy as needing him the most. That left Starwind to Savil.

She gave him her hands and helped him to his feet; he shook his head to clear it, then pulled his hair back over his shoulders. “God of my fathers,” he said, passing his hand over his brow. “I feel as if I have been kicked across a river.’’

Savil ran a quick check over him, noted a channel-pulse and cleared it for him. “What happened?” she asked urgently, keeping one hand on his elbow to steady him. “It looks like a mage-war in here.”

“I believe I badly frightened the boy,” Starwind said, unhappily, checking his hands for damage. “I intended to frighten him a little, but not so badly as I did. He was supposed to be calling lightning and he was balking. He plainly refused to use the power he had called. I grew impatient with him – and I cast the image of wyrsaat him. He panicked; and not only threw his own power, he pulled power from the valley-node. Then he realized what he had done and aborted it the only way he could at that point, pulling it back on himself.” Starwind gave her a reproachful glance. “You told me he could sense the node, but you did not tell me he could pull from it.”

“I didn’t know he could, myself. Great good gods – shayana, it was wyrsathat his shay ‘kreth ‘ashkecalled down on his enemies, didn’t I tell you?” Savil’s gut went cold; she bit her lip, and looked over her shoulder at Moondance and his patient. The Healer-Adept was kneeling beside the boy with both hands held just above his brow. “Lord and Lady, no wonder he nearly blew the place apart!”

Starwind looked stricken to the heart, as Moondance took his hands away from the boy’s forehead and put his arm under Vanyel’s shoulder to pick him up and support him in a half-sitting position. “You told me – but I had forgotten. Goddess of my mothers, what did I do to the poor child?”

“Ashke, what did you do?” Moondance called worriedly, one hand now onVanyel’s forehead, the other arm holding him. “The child’s mind is in shock.”

“Only the worst possible,” Starwind groaned. “I threw at him an image of the things his love called for vengeance.”

“Shethka. Well, no help for it; what is done cannot be unmade. Ashke, I will put him to bed, and call his Companion, and we will deal with him. We will see what comes of this.” He picked the boy up, and strode through the pass-through without a backward glance.

“Ah, gods – this was going well, until this moment,” Starwind mourned. “He was gaining true control. Gods, how could I have been so stupid?”

“It happens,” Savil sighed, “And with Van more so than with anyone else, it seems. He almost seems to attract ill luck. Shayana, why did you throw anything at him, much less wyrsa?”

“He finally is willing enough to learn the controls, the defensive exercises, but notthe offensive.” Starwind put his palms to his temples and massaged for a moment, a pain-crease between his eyebrows. “And if he does not master the offensive – “

“The offensive magics will remainwithout control,” Savil said grimly, the smell of scorched rock still strong about her. “Like Tylendel. I couldn’t get past his trauma to get those magics fully under conscious lock. I should have brought himto you.”

“Wingsister, hindsight is ever perfect,” Starwind spared a moment to send a thread of wordless compassion her way, and she smiled wanly. “The thing with this boy – I told you, he hadthe lightnings in his hand, I could see him holding them, but he would not cast them. I thought to frighten him into taking the offense.” He lowered his hands and looked helplessly at Savil. “He is a puzzle to me; I cannot fathom why he will not fully utilize his powers.”

“Because he still doesn’t understand why he should, I suppose,” Savil brooded, rocking back and forth on her heels. “He can’t see any reason to use those powers. He doesn’t want to help anyone, all he wants now is to be left alone.”

Starwind looked aghast. “But – so strong– how can he not – ‘‘

“He hasn’t got the hunger yet, shayana, or if he’s got it, everything else he’s feeling has so overwhelmed him that all he can register is his own pain.” Savil shook her head. “That, mostly, would be my guess. Maybe it’s that he hasn’t ever seen a reason to care for anyone he doesn’t personally know. Maybe it’s that right now he has no energy to care for anyone but himself. Kellan tells me Yfandes would go through fire and flood for him, so there has to be somethingthere. Maybe Moondance can get through to him.”

“Only if he survives what we do to him,” Starwind replied, motioning her to precede him into the pass-through, and sunk in gloom.

Vanyel woke with an ache in his heart and tears on his face; the image of the wyrsahad called up everything he wanted most to forget.

He could tell that he was lying on his bed, still clothed, but his hands and forearms felt like they’d been bandaged and the skin of his face hurt and felt hot and tight.

The full moon sent silver light down through the skylight above his head. He saw the white rondel of it clearly through the fronds of the ferns. His head hurt, and his burned hands, but not so much as the empty place inside him, or the guilt – the terrible guilt.

‘Lendel, ‘Lendel - my fault.

He heard someone breathing beside him; a Mindtouch confirmed that it was Moondance. He did not want to talk with anyone right now; he just wanted to be left aJone. He started to turn his face to the wall, when the soft, oddly young-sounding voice froze him in place.

“I would tell you of a thing – “

Vanyel wet his lips, and turned his head on the pillow to look at the argent-and-black figure seated beside him on one of the strange “chairs” he favored.

Moondance might have been a statue; a silvered god sitting with one leg curled beneath him, resting his crossed arms on his upraised knee, face tilted up to the moon. Moonlight flowed over him in a flood of liquid silver.

“There was a boy,” Moondance said, quietly. “His name was Tallo. His parents were farmers, simple people, good people in their way, really. Very tied to their ways, to their land, to the cycle of the seasons. This Tallo… was not. He felt things inside him that were at odds with the life they had. They did not understand their son, who wanted more than just the fields and the harvests. They did love him, though. They tried to understand. They got him learning, as best they could; they tried to interest the priest in him. They didn’t know that what the boy felt inside himself was something other than a vocation. It was power, but power of another sort than the priest’s. The boy learned at last from the books that the priest found for him that what he had was what was commonly called magic, and from those few books and the tales he heard, he tried to learn what to do with it. This made him – very different from his former friends, and he began to walk alone. His parents did not understand this need for solitude, they did not understand the strange paths he had begun to walk, and they tried to force him back to the ways of his fathers. There were – arguments. Anger, a great deal of it, on both sides. And there was another thing. They wished him to wed and begin a family. But the boy Tallo had no yearning toward young women – but young men– that was another tale.”

Moondance sighed, and in the moonlight Vanyel saw something glittering wetly on his eyelashes. “Then, the summer of the worst of the arguments, there came a troupe of gleemen to the village. And there was a young man among them, a very handsome young man, and the boy Tallo found that he was not the only young man in the world who had yearnings for his own sex. They quickly became lovers – Tallo thought he had never been so happy. He planned to leave with the gleemen, to run away and join them when they left his village, and his lover encouraged this. But it happened that they were found together. The parents, the priest, the entire village was most wroth, for such a thing as shay’a’chernwas forbidden even to speak of, much less to be. They – beat Tallo, very badly; they beat the young gleeman, then they cast Tallo and his lover out of the village. Then it was that the young gleeman spurned Tallo, said in anger and in pain what he did not truly mean, that he wanted nothing of him. And Tallo became wild with rage. He, too, was in pain; he had suffered for this lover, been cast out of home and family for his sake, and now he had been rejected – and he called the lightning down with his half-learned magic. He did not mean to do anything more than frighten the young man – but that was not what happened. He killed him; struck him dead with the power that he could not control.”