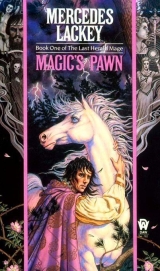

Текст книги "Magic's Pawn"

Автор книги: Mercedes Lackey

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

Eight

Vanyel stared nervously at his own reflection in the window – a specter, pale and indistinct; ghostlike, with dark hollows for eyes. Beyond the glass, night blanketed the gardens; a moonless night, a night of wind and cloud and no light at all, not even starlight.

Sovvan-night; the night of celebration of the harvest, but also the night set apart for remembering the dead of the year past. The night when – so most traditions held – the Otherworld was closer than on any other night. A night of profound darkness, like the one a moon ago when Staven had been slain.

Savil was with the rest of the Heralds, mourning theirdead of the year. Donni and Mardic, having no one in need of remembrance, were with some of the other trainees at a Palace fete, indulging in a certain amount of the superstitious foolery associated with Harvestfest that was also a Jpart of Sovvan-night, at least for the young.

Lord Evan Leshara had gone home to Westrel Keep. Presumably well satisfied with himself. There was no doubt in Vanyel’s mind that Lord Evan had somehow extracted enough good information from what had been fed to him to deduce exactly what bait would serve best to lure Staven to his death. They had tried to use him – and had ended up being used by him.

And that was a blackly bitter thought.

Tylendel and Vanyel had been left alone in the suite -

Tylendel and Vanyel would not be mewed up in the suite much longer.

“Are you ready?” Tylendel asked from the door behind him.

Vanyel nodded, and pulled the hood of his dark blue cloak up over his head, trying not to shiver at his own reflection. With the hood shrouding his face, he looked like an image of Death itself. Then Tyiendel moved silently to his side, and there were twoof the hooded figures reflected in the clouded glass; Death, and Death’s Shadow.

He shook his head to free it of such ominous thoughts, as Tyiendel opened the door and they stepped out into the cold, blustering night.

This morning he had slipped out into Haven and bought a pair of nondescript horses from a down-at-the-heels beast-trader, using most of the coin he and Tyiendel had managed to scrape together over the past three weeks. He’d taken them off into the west end of the city and stabled them at an inn just outside the city wall.

Tylendel had told Vanyel that before he worked the spell to take them within striking distance of the Leshara holding, he wanted-to be out of the easy sensing range of the Herald-Mages. They needed transportation, but it didn’t matter how broken-down the beasts were; their horses only needed to last long enough to get them an hour’s ride out of the city. After that it wouldn’t matter what became of them.

Obviously, riding Gala was totally out of the question. They weren’t taking Star or “borrowing” any of the true horses from the Palace stables, because if their absence were noticed, Tyiendel didn’t want any suspicions aroused until it was too late to stop them. Vanyel had concurred without an argument; if they couldn’t force their mounts through Tylendel’s Gate – and the trainee had indicated that they might not be able to or might not want to – they were going to have to turn them loose to fend for themselves. He didn’t want to lose Star, and he didn’t want to be responsible for the loss of anyone else’s prized mount, either.

The ice-edged wind caught at their cloaks, finding all the openings and cutting right through the heavy wool itself. Vanyel was shivering long before they slipped past the Gate Guard at the Palace gates and on out into the streets of the city. The Guard was preoccupied with warming himself at the charcoal brazier beside the gate; he didn’t seem to notice them as they hugged the shadows of the side of the gate farthest from him and took to the cobblestoned street beyond.

Now they were out in the wealthiest district of the city. The high buildings on either side of them served only to funnel the wind right at them, or so it seemed. Tylendel, who was still not entirely steady on his feet, grabbed Vanyel’s arm and hung on. Vanyel could feel him shivering, partly with cold, but from the way his eyes were gleaming in the shadows of his hood, partly also with excitement.

These mansions of the wealthy and highborn were mostly dark tonight; the inhabitants were either at Temple services or attending the Harvestfest gathering at the Palace. Vanyel had notreceived an invitation – and although he was anything but displeased, he wasn’t entirely certain why he had not. His apparent about-face with regard to Tylendel had confused not only his own little circle, but the trainees and Heralds as well. And no one had enlightened them; Savil had reckoned that keeping the rumormongers confused would keep the real story from reaching Withen for a while and buy them additional time.

Assuming Lord Evan hadn’t told him, just for the pure spite of making things difficult for Tylendel and Tylendel’s lover. It would suit the man’s character.

Vanyel thought briefly of the Sovvan-fete he was missing. It was possible that those in charge of the festivities had assumed he would be staying at Tylendel’s side, especially tonight. It was also possible that they blamed him for Tylendel’s condition (Mardic had reported several stories to that effect) and were “punishing” him for his conduct.

Whatever the reason, this had proved to be too good an opportunity to slip out undetected to let pass by.

They turned a corner, and the buildings changed; now they were smaller, crowded closer together, and no longer hidden behind walls. Each had candles in the otherwise darkened windows – another Sovvan-custom. It was by the light of these candles that the two were finding their way; the torches that usually illuminated the street by night had long since blown out.

Tylendel had been growing increasingly strange and withdrawn in the past several days since Vanyel had purloined Savil’s magic books for him. Vanyel would wake up in the middle of the night to find him huddled in the chair, studying his handwritten copies of the two spells with fanatic and feverish concentration. During waking hours he would often stare for hours at nothing, or at a candleflame, and his conversation had become monosyllabic. The only time he seemed anything like his old self was when he’d begin a nightmare and Vanyel would wake him from it; then he would cry for a while on Vanyel’s shoulder, and afterward talk until they both fell asleep again. Thenhe sounded like the old Tylendel – not afraid to share his grief or his fears with the one he loved. But when day arrived, he would be back inside his shell, and nothing Vanyel would do or say could seem to crack that barrier.

Vanyel had long since begun to think that he would neverbe his old self again until his revenge had been accomplished, and he had begun to long for that moment with a fervor that nearly equaled his lover’s.

They reached the sector of shops and inns long before they saw another human out on the streets, and that was only the Nightwatch. The patrol of two men gave them hardly more than a passing glance; they were obviously unarmed except for knives, were too well-dressed to be street-toughs, and not flashy enough to be young high-borns out to find some trouble. The two men of the Watch gave them nearly simultaneous nods, curt and preoccupied, nods which they returned as the light from the Watchlantern in the hands of the rightmost one fell on them. Satisfied by what they saw, the Watch passed on, and so did they, bootheels clattering on the cobbles.

Here the buildings were only one or two stories tall, and the wind howled and ramped about them unimpeded. The quality and state of repair of these buildings – mostly shops, inns, lodging-houses and workshops – declined steadily and rapidly as they neared the west city-wall of Haven.

The Guards on the great gates of Haven were not in evidence tonight, although there was a viewport in the wall, and Vanyel could almost feel eyes on him as they passed below it. Obviously the Guards found as little to alarm them in the two younglings as the Watch had; they passed out under the wall with no challenge whatsoever.

Once outside the west wall, they were in the lowest district in the city. Vanyel led the way to the ramshackle inn where he’d left their sorry nags; fighting the wind every inch of the way, as it nearly tore the edges of his cloak out of his half-frozen hands.

The Red Nose Inn was brightly lit and full to bursting with roisterers; Vanyel heard their out-of-tune singing and hoarse laughter even over the moaning of the wind as they passed by the open door. Smoke and light alike spilled out that door, and the wind carried a random puff of the smoke into their eyes as they passed, a noisome smudge that made them cough and their eyes water for a moment before cleaner air whipped it out of their faces again. They ignored that open door and passed around the side of the inn to the dirty courtyard and the stabling area.

There was a single, half-drunk groom on duty, slumped on a stack of hay bales by the stable door, illuminated by a feebly burning lantern. His head lolled on his chest as he snored, smelling, even in this wind, as if he’d fallen into a vat of cheap beer. Tylendel waited in the shadows beyond reach of the light from the smoking lantern that had been hung in the lee of the stable door, while Vanyel shook the man’s shoulder until he roused up.

“Eh?” the man grunted, peering into the shadows under Vanyel’s hood in an unsuccessful attempt to make out his features. His breath was as foul as his clothing; his face was filthy and unshaven, and his hair hung around his ears in lank, greasy ringlets. “What ye want, then? Where be yer nags?’’

“Already here,” Vanyel replied, in a tone as adult, brusque, and gruff as he could manage. “Here – “ He shoved the claim-chits at the groom, together with two silver pieces. The man stared stupidly at them for a moment, blinking in surprise, as if he were having trouble telling the chits from the coins. Then he grinned in sudden comprehension, displaying a mouthful of half-rotten teeth, and nodded.

“ ‘Muff celebratin’, eh, master? Just ye wait, just ye wait right here.” He shoved the coins and chits together into the pocket in the front of his stained, oily leather apron, heaved himself up off his couch of hay bales, and staggered inside the stable door. He emerged a great deal sooner than Vanyel would have thought possible, leading a pair of scruffy-looking, nondescript brown geldings that were already saddled and bridled with patched and worn tack. Vanyel squinted at them in the smoky light, trying to make out if they were the same ones he’d bought this morning, then realized that it didn’t matter if they were or not. It wasn’t as if the horses he’d purchased were any kind of prize specimens – in fact, if these weren’t“his” horses, they were likely as not to be an improvement over the ones he’d bought!

He took the reins away from the groom without another word, turned, and led them across the dirt court to where Tylendel was waiting, huddled against the inn wall in a futile attempt to avoid the biting wind. When he looked back over his shoulder, he could see that the groom had already flopped down on the straw bales and resumed his interrupted nap.

He handed Tylendel the reins of the best of the two mounts, and scrambled into his own saddle. His flea-bitten beast skittered sideways in an attempt to avoid being mounted, and gave a half-hearted buck as Vanyel settled into his seat. Vanyel made a fist and gave it a good rap between the ears; the nag stopped trying to rid itself of its rider and settled down.

The spine of his saddle was broken; the horse itself was sway backed, and its gait was as rough as he’d ever had the misfortune to encounter. He hoped, as Tylendel took the lead and they headed down Exile’s Road into the west, that they wouldn’t be riding for too very long.

* * *

The wind had died down – at least momentarily – when Tylendel finally stopped. It was so dark that the only way he really knew that Tylendel had pulled up was because the sound of hooves on the hard surface of the road ahead of him stopped. They’d trusted to the fact that Exile’s Road was lined on either side with hedges to keep their sorry beasts on the roadway. He kicked at his own mount and forced it forward until he could feel the presence of Tylendel and his horse bulking beside him.

There was a flare of light; Vanyel winced away from it – it was quite painful after the near-total darkness of the last candlemark or so. When he could bear to look again, he saw that Tylendel had dismounted and was leading his horse, a red ball of mage-light bobbing along above his head.

He scrambled off of his own mount, glad enough to be out of that excruciatingly uncomfortable saddle, snatched the reins of the beast over its head, and hastened to catch up.

“Are we far enough away yet?” he asked, longing for even a single word from the trainee to break the silence and tension. Tylendel’s face was drawn and fey, and strained; Tylendel’s attention was plainly somewhere else, his whole aspect wrapped up in the kind of terrifying concentration that had been all too common to him of late.

“Almost,” he replied, after a long and unnerving silence. His voice had a strange quality to it, as if Tylendel was having to work to get even a single word out past whatever it was he was concentrating on. “I’m – looking for something…”

Vanyel shivered, and not from the cold. “What?”

“A place to put the Gate.” They came to a break in the hedge. No – not a break. When Tylendel stopped and led his horse over to it, Vanyel could see that it was the remains of a gated opening in the hedge, long since overgrown. Beyond the gap something bulked darkly in the dim illumination provided by the mage-light. Tylendel nodded slightly. “I thought I remembered this place,” .he muttered. He didn’t seem to expect a response, so “Vanyel didn’t make one.

It was obvious that the horses were not going to be able to force themselves through so narrow a passage; Tylendel stripped the bridle from his, hung it on the saddlebow, and gave the gelding a tremendous slap on the hip that made it snort with surprise and sent it cantering off into the darkness. Vanyel did the same with his, notsorry to see it go, and turned away from the road to see that Tylendel had already forced his way past the gap in the hedge and was now out of sight. Only the reddish glow of the mage-light through the leafless branches of the hedgerow showed where he had gone.

Vanyel shoved his way past the branches, cursing as they caught on his cloak and scratched at his face. When he emerged, staggering, from the prickly embrace of stubborn bushes, he found that he was standing knee-deep in weeds, in what had been the yard of a small building. It could have been anything from a shop to a cottage, but was now going to pieces; the yard was as overgrown as the gate had been. The building seemed to be entirely roofless and the door and windows were mere holes in the walls. Tylendel was examining the remains of the door with care.

The gap where the door had been was a large one, easily large enough for a horse and rider to pass through. Tylendel nodded again, and this time there was an expression of dour satisfaction on his face. “This will do,” he said softly. “Van, think you’re ready?”

Vanyel took a deep breath, and tried to relax a little. “As ready as I’m ever likely to get,” he replied.

Tylendel turned and took both Vanyel’s hands in his; he looked searchingly into Vanyel’s eyes for a long moment. “Van, I’m going to have to force that link between us wide open for this to work. I may hurt you. I’ll try not to, but I can’t promise. Are you still willing to help me?”

Vanyel nodded, thinking, I’ve come this far; it would be stupid to back out at this point. Besides – he needs this. How can I not give it to him?

Tylendel closed his eyes; his face froze into as impassive a mask as Vanyel had ever worn. Vanyel waited, trembling a little, for something to happen.

For a long while, nothing did. Then -

Rage flamed up in him; a consuming, obsessive anger that left very little room for anything else. One thing mattered: Staven was dead. One goal drove him: deal the same painful death to Staven’s murderers. There was still a tiny corner of his mind that could think for itself and wonder at the overwhelming power of Tylendel’s fury, but that corner had been locked out of any position of control.

The truism ran “Pain shared is pain halved” – but this pain was doubled on being shared.

He turned to face the ancient doorway without any conscious decision to do so, Tylendel turning even as he did. He saw Tylendel raise his arms and cast a double handful of something powderlike on the ground before the door; heard him begin a chant in some strange tongue and hold his now empty hands, palm outward, to face that similarly empty gap.

He felt something draining out of him, like blood draining from a wound; and felt that it was taking his strength with it.

The edges of the ruined doorway were beginning to glow, the same sullen red as the mage-light over Tylendel’s head; like the muted red of embers, as if the edge of the doorway smoldered. As more and more of Vanyel’s energy and strength drained from him, the ragged border’ brightened, and tiny threads of angry scarlet wavered from them into the space where the door had stood. More and more of these threads spun out, waving like water-weeds in a current, until two of the ends connected across the gap.

There was a surge of force out of him, a surge that nearly caused his knees to collapse, as the entire gap filled with a flare of blood-red light -

Then the light vanished – and the gap framed, not a shadowed blackness, but a garden; a formal garden decorated for a festival, and filled with people, light and movement.

He had hardly a chance to see this before Tylendel grabbed his arm and pulled him, stumbling, across the threshold. There was a moment of total disorientation, as though the world had dropped from beneath his feet, then-

Sound: laughter, music, shouting. He stood, with Tylendel, facing that garden he had seen through the ruined doorway, and beyond the garden, a strange keep. Lanterns bobbed gaily in the branches of a row of trees that stood between them and the gathered people, and trestle tables, spread with food and lanterns, were visible on the farther side. Near the trees was a lighted platform on which a band of motley musicians stood, playing with a vigor that partially made up for their lack of skill. Before the platform a crowd of people were dancing in a ring, laughing and singing along with the music.

Vanyel’s knees would not hold him; as soon as Tylendel let go of his arm, his legs gave way, and he found himself half-kneeling on the ground, dizzy, weak and nauseated. Tylendel didn’t notice; his attention was on the people dancing.

“They’re celebrating,”Tylendel whispered, and the anger Vanyel was inadvertently sharing surged along the link between them. “Staven’s dead, and they’re celebrating!”

That small, rational corner still left to Vanyel whispered that this was onlya Harvestfest like any other; that the Leshara weren’t particularly gloating over an enemy’s death. But that logical voice was too faint to be heard over the thunder of Tylendel’s outrage. A wave of dizziness clouded his sight with a red mist, and he could hear his heart pounding in his ears.

When he could see again, Tylendel had stepped away from him, and was standing between him and the line of trees with his hands high over his head. From Tylendel’s upraised hands came twin bolts of the same vermilion lightning that had lashed the pine grove a moon ago. Only thislightning was controlled and directed; and it cracked across the garden and destroyed the trees standing between him and the gathered Leshara-kin in less time than it took to blink.

In the wake of the thunderbolt came startled screams; the music ended in a jangle of snapped strings and the squawk of horns. The dancers froze, and clutched at each other in clumps of two to five. Tylendel’s mage-light was blazing like a tiny, scarlet sun above his head; his face was hate-filled and twisted with frenzy. Tears streaked his face; his voice cracked as he screamed at them.

“He’s dead, you bastards! He’s dead, and you’re laughing, you’re singing! Damn you all, I’ll teach you to sing a different song! You want magic? Well, here’s magic for you– ‘‘

Vanyel couldn’t move; he seemed tethered to the still-glowing Gate behind him. He could only watch, numbly, as Tylendel raised his hands again – and this time it was not lightning that crackled from his upraised hands. A glowing sphere appeared with a sound of thunder, suspended high above him. About the size of a melon, it hung in the air, rotating slowly, a smoky, sickly yellow. It grew as it turned, and drifted silently away from Tylendel and toward the huddled Leshara-folk, descending as it neared them, until it came to earth in the center of the blasted, blackened place where the trees had been a moment before.

There it rested; still turning, still growing, until it had swelled to twice the height of a man.

Then, between one heartbeat and the next, it burst.

Another wave of disorientation washed over him; Vanyel blinked eyes that didn’t seem to be focusing properly. Where the globe had rested there seemed to be a twisting, twining mass of shadow-shapes, shapes as fluid as ink, as sinuous as snakes, shapes that were thereand not thereat one and the same time.

Then they slid apart, those shapes, separating into five writhing mist-forms. They solidified -

If some mad god had mated a viper and a coursing-hound, and grown the resulting offspring to the size of a calf, the result mighthave looked something like the five creatures snarling and flowing lithely around one another in the gleaming of Tylendel’s mage-light. In color they were a smoky black, with skin that gave an impression of smooth scales rather than hair. They had long, long necks, too long by far, and arrowhead-shaped heads that were an uncanny mingling of snake and greyhound, with yellow, pupilless eyes that glowed in the same way and with the same shifting color that the globe that had birthed them had glowed. The teeth in those narrow muzzles were needle-sharp, and as long as a man’s thumb. They had bodies like greyhounds as well, but the legs and tails seemed unhealthily stretched and unnaturally boneless.

They regarded Tylendel with unwavering, saffron eyes; they seemed to be waiting for something.

He quavered out a single word, his voice breaking on the final, high-pitched syllable – and they turned as one entity to face the cowering folk of Leshara, mouths gaping in unholy parodies of a dog’s foolish grin.

But before they had flowed a single step toward their victims, a shrill scream of equine defiance rang out from behind Vanyel.

And Gala thundered through the Gate at his back, pounding past him, then past Tylendel, ignoring the trainee completely.

She screamed again, more anger and courage in her cry than Vanyel had ever thought possible to hear in a horse’s voice, and skidded to a halt halfway between Tylendel and the things he had called up. Shewas glowing, just like she had during ‘Lenders fit; a pure, blue-white radiance that attracted the eye in the same way that the yellow glow of the beasts’ eyes repelled. She continued to ignore Tylendel’s presence entirely, turning her back to him; rearing up to her full height and pawing the air with her forehooves, trumpeting a challenge to the five creatures before her.

They reversed their positions in an instant as her hooves touched the ground again, facing her with silent snarls of anger. She pawed the earth, and bared her teeth at them, daring them to try to fight her.

“Gala!” Tylendel cried in anguish, his voice breaking yet again. “Gaia! Don’t– “

She turned her head just enough to look him fully in the eyes – and Vanyel heard her mental reply as it rang through Tylendel’s mind and heart and splintered his soul.

:Ido not know you: she said coldly, remotely. :You are not my Chosen.:

And with those words, the bond that had been between them vanished. Vanyel could feel the emptiness where ithad been – for he was still sharing everything Tylendel felt.

Tylendel’s rage shattered on the cold of those words.

And when the bond was broken, what took its place was utter desolation.

Vanyel moaned in anguish, sharing Tylendel’s agony, and the torment and bereavement as he called after Gaia with his mind and received not even the echo of a reply. Where there had been warmth and love and support there was now – nothing; not even a ghost of what had been.

The link between them surged with loss, and Vanyel’s vision darkened.

He heard Tylendel cry out Gala’s name in utter despair, and willed his eyes to clear.

And to his horror he watched her fling herself at the five fiends, heedless of her own safety.

They swarmed over and about her, their darkness extinguishing her light. He heard her shriek, but this time in pain, and saw the red splash of blood bloom vividly on her white coat.

He tried to stagger to his feet, but had no strength; his ears roared, and he blacked out.

He barely felt himself falling again, and only Tylendel’s scream of anguish and loss penetrated enough to make him fight his way back to consciousness.

He found himself half-sprawled on the cold ground. He shoved himself partially erect despite his spinning head, and looked for Gala -

But there was no Companion, no fight. Only a mutilated corpse, sprawling torn and ravaged, throat slashed to ribbons, the light gone from the sapphire eyes. Tylendel was on his knees beside her, stroking the ruined head, weeping hoarsely.

Beside her lifeless body lay one of the five monstrosities, head a shapeless pulp. The others flowed around the Companion’s body, as if waiting for the corpse to rise again so that they could attack it. Two of the others limped on three legs – but two were still unharmed, and given what they had done to Gala in a few heartbeats, two would be more than enough to slaughter every man, woman, and child of the Leshara.

Finally they left off their mindless, sharklike circling, and turned to face the terrified celebrants. They took no more notice of Tylendel than of the dead Companion.

A man bolted from the crowd. With a start, Vanyel recognized him for Lord Evan. Whether he meant to attack the beasts, or simply to flee, Vanyel couldn’t tell. It really didn’t matter much; one of the beasts that was still unhurt flashed across the intervening space and caught him. He did not even have time to cry out as it disem-bowled him.

A woman screamed – and that seemed to signal the beasts to move again. They began to ooze in a body toward their victims -

And a bolt of brilliantly white lightning cracked from behind Vanyel to scorch the earth before the leader.

There was a pounding of hooves from the Gate. Vanyel was momentarily blinded by the light and by another surge of weakness that sent him sagging back to the ground.

When his eyes cleared again, there were three whiteclad Heralds and their three Companions closing on the fiends, lightning crackling from their upraised hands .They were using the lightnings to herd the beasts into a tight little knot and barring their path to their prey.

He barely had time to recognize two of the three as Savil and Jaysen before battle was joined.

Once again he started to black out, feeling as if something was trying to pull his soul out of his body. He fought against unconsciousness, though he felt as if he had nothing left to fight with;both the rage and the despair were gone now, leaving only an empty place, a void that ached unbearably.

He felt a tiny inflowingof strength; it wasn’t much, but it was enough to give him the means to fight the blackness away from his eyes, to fight off the vertigo, and to finally get a precarious hold on the world again.

The first thing he saw was Tylendel; still on his knees, but no longer weeping. He was vacant-eyed, white as bleached linen, and staring at his own blood-smeared hands. Where the five creatures had been there was now nothing; only the mangled body of Gala and the burned and churned-up earth.

Taking her hand away from his shoulder was Savil – her face an unreadable mask.

Savil pulled her attention away from Tylendel, who was slumped in a kind of trance of despair beside her, and back to what Vanyel was telling the other two Heralds.

“… then she said, ‘I don’t know you, you aren’t my Chosen,’ “ the boy whispered, eyes dull and mirroring his exhaustion, voice colorless. “And she turned her back on him, just turned away, and charged those things.”

“Buying time for us to get here,” Jaysen murmured, his voice betraying the pain he would not show. “Oh, gods, the poor, brave thing – if she hadn’t bought us those moments, we’d have come in on a bloodbath.”

“She repudiatedhim,” said Lancir, the Queen’s Own, as if he did not believe it. “She repudiated him, and then-”

“Suicided,” Savil supplied flatly, her own heart in turmoil; aching for Tylendel, for the loss of Gala, for all the things she should have seen and hadn’t.. “Gods, she suicaided. She knew, she had to know that no single Companion could face a pack of wyrsaand survive.”

Tylendel sat where they had left him; unseeing, unspeaking – all of hell in his eyes. Mage-lights of their own creation bobbed overhead, pitilessly illuminating everything.

Jaysen contemplated Savil’s trainee for a long moment, but said nothing, only shook his head slightly. Then he spared a glance for Vanyel, and frowned; Savil heard his thought. :The boy is still tied to the Gate, sister. He grows weaker by the moment. If you want him undamaged -:

Unspoken, but not unfelt, was the vague thought that perhaps it would be no bad thing if Vanyel were to be “forgotten” until it was too late to save him from the aftereffects of the Gate-magic. That undercurrent of thought told Savil that Jaysen placed all of the blame for this squarely on Vanyel’s shoulders.