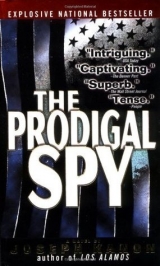

Текст книги "The Prodigal Spy"

Автор книги: Joseph Kanon

Жанры:

Шпионские детективы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

“Call Uncle Larry,” Nick said.

“Larry?”

“He’ll know what to say. Before they come back.”

His mother shook her head. “It doesn’t matter,” she said, dropping her hand.

“It does. They’ll blame him. Where is he?”

“I don’t know, Nick.”

“I’m good at secrets. I’ll never tell. Never.”

“So many secrets,” his mother said vaguely. “You don’t understand. I don’t know.”

“But he’s safe?”

She nodded.

“Mr Welles won’t get him?”

She looked at him, and then, as if she were starting to laugh, her voice cracked and she sobbed out loud, so that Nora looked over from the phone table. “No,” she said, her voice still in the in-between place. “Not now. Nobody will.”

“Why not?” Nick whispered, his voice throaty and urgent. “Why not?”

Then she did laugh, the other side of the crying. “He’s gone,” she said wispily, moving her hand in the air. “He’s fled the coop.”

Before Nick could take this in, Nora loomed in front of them, her face white and dismayed.

“I’ll take her upstairs,” Nick said quickly. “She’s upset.” It was his father’s voice.

Nora stared at him, more startled by his self-possession than by his mother’s behavior. When he took his mother’s elbow to lead her out of the room, Nora moved aside, stepping back out of their path.

He led her down the hall, but at the stair railing she stopped, slipping out of his hand. “I’ll be all right,” she said softly, her voice coming back. “I’ll just lie down for a while.”

But Nick stopped her, placing his hand over hers on the rail. “Why won’t they get him?”

His mother turned her head, looking for Nora, then lowered it. “He’s not here,” she said finally. “He’s left the country.”

She took in his wide eyes, then looked nervous again, so that Nick knew she hadn’t meant to tell. He felt lightheaded, the same frightened giddiness as that time when their car had skidded on the ice coming down the hill from the cabin, spinning them sideways. Steer into the slide, his father had said aloud, giving himself instructions, gripping the wheel hard until finally they connected with the road again and he heard the solid crunching of snow. There wasn’t time to think, just to steer.

“Mom?” he said, looking into her frightened eyes. “Don’t tell anyone else.”

By the next day his father was no longer unavailable for comment: he was missing. There were more men outside, and Nick saw that one was now watching the back too. Nora moved into the guest room, bringing her things over in a small valise, settling in for a siege. The radio said his father had been distraught at the news of the Cochrane suicide, but how did they know? Mr Benjamin came, and Uncle Larry, and the police again, two men from the FBI. The phone rang.

Each day that week, as the spill spread, the headlines grew larger, so that the mystery itself became the news, begging for an answer. Welles appealed to his father to come out of hiding, implying that he had become guilty simply by being absent. Still, there was a new hesitancy in his voice, as if, having pushed one victim to a desperate act, he did not want to be blamed for another. Walter Kotlar had eluded him after all. There was an article about the rot in the State Department, the pumpkin field again, the China lobby, the unaccountable disappearance, proof of some larger conspiracy. But the story refused to stay political. The mystery seemed too complete for that–it frightened people. Nobody ran away from a hearing. It seemed to belong instead to the tabloid world of personal scandal and WANTED posters and cars speeding away in the night, a more familiar fall from grace. Was he still alive, sitting in some hotel room with his own open window? One day the papers ran some old family pictures. Nick and his mother, she squatting next to him proudly on the pavement as he showed off his new suit to the camera. His father as a young man, smiling. The house on 2nd Street. The car, still parked in the garage. All the pictures of a crime story, without any crime.

All week, as the newspapers grew louder and louder until finally, like a fire out of oxygen, they choked and went out, what struck Nick was the quiet in the house. With all the phones and visitors and black headlines that seemed to carry their own sounds, hours went by when there was nothing to hear but the clock. People spoke in low voices, when they spoke at all, and even Nora walked softly, not wanting to disturb the patient.

His mother was the patient. She spent long stretches sitting on the couch, smoking, not saying a word. Her silence, her intense concentration on nothing at all, frightened him. At night, alone, she drank until finally, her eyes drooping, she would curl up on the couch, avoiding her bedroom, and Nick would wait until he heard her steady breathing before he tiptoed over and covered her with the afghan. In the morning, she never wondered where it had come from. She seemed to forget everything, even what had really happened. She told the police–a relief– that his father had left Sunday morning, just as Nick had said. Yes, they’d played Scrabble. No, he hadn’t seemed upset. When Uncle Larry suggested she get away for a few days until things died down, she said to him in genuine surprise, “I can’t, Larry. I have to be here, if he calls.” The secret, at least, was safe. She had begun living in Nick’s story.

“Are you all right for money?” Larry said.

“I don’t know. Walter took care of all that.”

“You have to know, Livia. Shall I go through his things? Would you mind?”

She shrugged. “It’s all in the desk. At least I suppose it is. The FBI went through it yesterday. I don’t think they took anything away.”

“You shouldn’t let them do that, Livia,” Larry said, a lawyer. “Not without a warrant.”

“What’s the difference, Larry? We don’t have anything to hide,” his mother said, and meant it.

The FBI came often now. In an unexpected seesaw of attention, as the newspapers grew bored with the story, the FBI became more interested. They went through his father’s papers, opened the wall safe, asked the same questions, and then went away, as much in the dark as before. His father had signed a power of attorney for her on Saturday, which seemed suspicious, but his mother didn’t know anything about it. And what, anyway, did they suspect? In the quiet study, everything was in order.

Nick grew quiet too. He wanted to go over things with his mother, plan what to do, but she didn’t want to talk, so he sat listening to the sounds of the house. He thought of everything that had happened, every detail, studying the Cochrane photograph to jolt him into some idea for action, but nothing came back but the creak of floorboards, a windowpane shaking back at the wind, until it seemed that the house was giving up too, disintegrating with them. He read the Hardy Boys books he had got for Christmas, with their speedboats and roadsters and mysteries that were always solved. They rescued their father in one, wily and resourceful. One day, after the snow melted, he walked down A Street to check on the drain, but the shirt was gone, and he barely paused at the corner before turning back.

It was his decision to go back to school, stifled finally by the airless house. When he opened the door that Monday, the reporters swarmed around, expecting his mother, then backed away to let him pass, like the water of the Red Sea. “Hi, Nick,” one of the regulars said, and he gave a shy wave, but they let him alone. At school, the lads backed away too, nodding with sidelong glances, deferential to his notoriety. His teacher pretended he’d been out sick and apologetically piled him with back homework. She never called on him in class. He sat quietly, taking notes, then went home and worked all evening while his mother sat smoking, still drifting. He finished all the make-up work in three days, turning in assignments that were neater and more complete than before, because now it was important to be good, to be blameless.

In the weeks that followed, nothing changed at home, but outside the reporters dwindled and at school people began to forget that anything had happened. When Welles suspended the hearings, the papers barely noticed. As Uncle Larry had predicted, things moved on. And it was Larry who brought his mother back.

“You can’t just sit in the house. I’m taking you to New York for the weekend.”

“To do what?”

“Go to a show, go out to dinner. Get dressed up and show your pretty face all over town,” he said, winking at Nick, Van Johnson again, cheerful and take-charge.

“I can’t.”

“Yes, you can. Livia, you can’t sit here. You’ve got to get on with things.”

“By going to New York with you?”

Larry looked at her and smiled. “For a start. We’ll take the train. I’ll pick you up here at five. Five, no later. And no buts,” he said, waving his forefinger.

Surprisingly, she went. Nora stayed the weekend and she and Nick went to the movies, treating themselves to tea at the Willard. In the long lobby of red carpets and potted palms, no one noticed them. On Sunday, when they went to meet his mother at Union Station, he glanced at the telephone booth, then averted his eyes, as if he were being watched. But his mother seemed better, the quiet around her beginning to thaw, like the melting snow.

It was only at night that it came back, the dread. It was the not knowing. Everyone acted as if his father were dead, but Nick knew he wasn’t. He was somewhere. Nick lay under the covers watching the tree branch and tried to play the cabin game. Over the years, they’d thought of a lot of places where the wind was blowing–the cabin in the mountains, a tent in the desert, that big hotel at the Grand Canyon where they’d gone one summer–but Nick couldn’t picture any of them. Instead there was the committee room, Welles glowering and accusing. A body falling in the cold. The strange walk to the telephone booth. And then, always, the back courtyard filling with snow.

I hope you die, his mother had said. But she hadn’t meant that. Nick just wanted to know, and then he could rest. It seemed to him that their lives on 2nd Street had ended without any explanation. There had to be a reason. The hearings were starting again. They were looking for more Communists. So things went on. Was that all it had been? Politics, a piece of history? The trouble with history, his father had said, is that you have to live through it. But he hadn’t meant this, half-living in a mystery. One day it will all seem like a dream. But it wouldn’t, just the same mystery. That was the dread: he would never know.

His mother ended it that spring by selling the house. They would start over in New York, where nobody cared, and Nick would go to Rhode Island, where Father Tim had arranged for a place at his old school. Tim was taking them there himself, in the big DeSoto he drove like a carriage, hands on either side of the wheel as if he were holding reins.

Nick went with him for gas while his mother finished packing–an excuse, Nick suspected, for one of Father Tim’s chats. But Tim was bubbly, as far away from homilies as a man on a picnic. They drove around the Mall, a last tour. “You’ll like the Priory,” he said. “Of course, people always say that about their schools. I suppose they’re really remembering themselves when they were young.” Nick looked over at him, unable to imagine the ruddy face over the white collar as anything but grown up. “But this time of year,” he continued, taking one hand away to gesture to the tree blossoms, “well, you won’t find a finer sight. And then you’ve got Newport down the road. All the boats. I used to love that. Hundreds of sails, all across the bay.” He stopped, aware of Nick’s silence. “You’ll like it,” he repeated. “You’ll see.”

“My father wouldn’t like it,” Nick said. “He didn’t want me to go to a Catholic school.”

Father Tim didn’t say anything to that. Nick watched him shift uncomfortably in his seat, avoiding the subject, his father’s name like a cloud over the bright day.

“Well, give it a chance,” Father Tim said. “You’ll see. But a fair chance, mind. You don’t want to be a burden to your mother. Not now. She’s had worries enough to last a lifetime. Rose isn’t as strong as she looks. It’s been a difficult time for her, you know.”

What about me? Nick wanted to say, but he was quiet. Then, “Why do you call her Rose?”

Father Tim smiled. “Well, she was Rose when I first knew her. She hated ‘Livia’ in those days. Like a Roman wife, she said. You know, Calpurnia. Names like that.” He smiled again, glad to reminisce. “She was just Rose Quinn then. The prettiest girl at Sacred Heart.”

“Maybe you should have married her,” Nick said, curious to see if his father’s joke had been right.

“Well, I married the church,” Father Tim said, but he’d misunderstood Nick and looked at him, troubled. “He’s still your father, Nick. No matter what.”

This was so far from what Nick had been thinking that he didn’t know what to say. Instead, he changed the subject. “Is it a sin to wish somebody would die? To say it, I mean.”

“Yes,” Father Tim said, “a great sin.” Then, misunderstanding again, “You don’t wish that, do you? No matter what he’s done.”

“No,” Nick said. “I don’t.” But he was disconcerted. Tim had opened a different door. What did Tim think his father had done?

They stopped for a red light and Nick looked across at the Smithsonian, surrounded by flowering trees.

“Of course you don’t,” Father Tim said. “Anyway, that’s all past now. You’ll both have a fresh start.”

But not together, Nick thought. He remembered the night his father went away, his mother clinging to Nick. He’d imagined going on like that, just the two of them. Now it seemed she’d be better on her own, putting Nick behind her with everything else. Maybe it was because he looked like his father, a visual reminder of what they were all supposed to forget.

“It’s not easy making a new life,” Father Tim said, as if they’d already disposed of the old. “But she’ll have you to help her now.”

This struck Nick as unfair, coming from the man who’d arranged to send him away, but he said nothing.

“You’ll settle in before you know it,” Father Tim went on. “And it’s just a train ride from New York. You’ll make new friends. It’ll be a fresh start for you too.”

“They’ll know,” Nick said. “At school.”

Father Tim paused, framing an answer. “It’s not Washington, Nick. They’re a little out of the world up there. That’s one of the nice things about the old Priory. They don’t hear much.”

“I don’t care anyway,” Nick said, looking out the window at the Mall. They were climbing the hill now, up toward the Capitol.

“You mustn’t mind what people say, Nick,” Father Tim said gently. “We’re not responsible for what our parents do. There’d be no end to it then. God only asks us to answer for ourselves.”

Nick said nothing, staring up at the Capitol, where everything had started. The flashbulbs and microphones. Maybe the committee was meeting now, banging gavels on the broad table, driving someone else away.

“If you commit suicide, do you go to hell?”

Father Tim glanced at him, visibly disturbed, then nodded. “Yes.”

“Always?”

“Yes, always. You know that, Nick. It’s a sin against God.”

“What if you helped? What if you made someone do it? Then what?”

“You mean that poor woman,” Father Tim said quietly. “We don’t know why she did that, Nick. You mustn’t judge. It may not have anything to do with your father.”

“No, not him. I was thinking about Mr Welles.”

Father Tim looked at him in surprise. “Mr Welles?”

“They said in the papers he was pressuring her. What if—”

“I don’t think that’s true, Nick. And even if it were, we mustn’t judge. He’s only doing what he thinks is right.”

“No. I saw him. He’s—” Nick searched for a word, but it eluded him. “Bad,” he finally said, knowing it was feeble and childish.

But his inadequacy seemed to relieve Father Tim. “Not necessarily,” he said smoothly. “I know it’s hard for you to understand. I don’t condone his methods either. But Communists are godless people, Nick. Sometimes a man does the right thing the wrong way. That doesn’t make him bad.”

Nick looked at him, stunned. Tim thought his father was godless–that’s what he’d done. We mustn’t judge. But Tim had judged and now he was going to save Nick, shipping him off to the priests and a world where people didn’t hear much. Save him from his father.

“Now this won’t do, you know,” Father Tim said, catching his look. “Taking the world on your shoulders like this. They’re still pretty young shoulders, Nick. The right and wrong of things–that’s what we spend our whole lives trying to figure out. When we grow up.” He smiled. “Of course, some people never do, or I’d be out of business, wouldn’t I?”

Nick saw that he was expected to smile back and managed a nod. There was nothing more to say, and now he was frightened again. Even Father Tim was with the others.

“What you’ve got to do now,” Father Tim said with a kind of forced cheer, “is get on with your own life. Never mind about your father and his politics and all the rest of it. That’s all over. You’ve got to look after your mother now. Right?”

Nick nodded again, pretending to agree.

“You have to let go,” Father Tim said quietly, his final point.

“He’s still my father,” Nick said stubbornly.

Father Tim sighed. “Yes, he is, Nick. And you’re right to honor him. Just as I do mine. That’s what we’re asked to do.”

“Your father’s dead.”

“But your father’s gone, Nick,” he said as if Nick hadn’t interrupted. “Maybe forever.” His voice was hesitant, struggling for the right tone. “He wanted it that way, I don’t know why. You can’t hold on to something that isn’t there. No good comes of that. It just makes it harder. He’s gone. I’m not telling you to forget him. But you have to go on. He’s like my father now. It’s an awful thing. And you so young. But it would be better if—” He floundered, slowing the car at the light, then turned to face Nick, his eyes earnest and reassuring. “You have to think of him as dead.”

He reached over and placed his hand on Nick’s, a gesture of comfort. Nick stared down at it, feeling the rest of his body slip away, skidding on ice. Nobody was going to help. Ever. Tim was waiting for him to agree. His father was godless and he was gone, better for everybody. It’s what they all wanted, all the others. If he nodded, Father Tim would pat his hand, the end of the lesson, and leave him alone. You’ve got to stop fighting with him, Uncle Larry had said in the study, and his father had.

“I’ll never do that,” Nick said quietly, sliding his hand out from under, free.

Father Tim glanced at him, disappointed, and took his hand back. He sighed again as he made the turn into 2nd Street. “You will, though, you know,” he said wearily, sure of the future. “Things pass. Even this. Nothing is forever. Except God.”

And suddenly Nick knew what he would do. He would remember everything, every detail. He looked at the street, the pink-and-white blossoms, the bright marble of the Supreme Court Building catching the sun, and tried to fix them in his mind. The curly iron railing in front of Mrs Bryant’s house. Lamp-posts. The forsythia bush. Then he saw the moving van, the big packing boxes scattered all over the sidewalk in front of his house like the mess their lives had become. The prettiest girl at Sacred Heart was standing on the stoop, her vacant eyes animated now, giving directions to the movers. Crates for the china. The end tables sitting on the patch of city yard, spindly legs wrapped in protective brown paper. Two men in undershirts sweating as they heaved a couch into the van. Suitcases by the door, ready. They were really going.

In that instant, as his mother saw the car and waved to them, picking her way through the boxes to the curb with a fixed smile, he thought, finally, that his heart would break. He wondered if it could literally happen, if sadness could fill the chambers like blood until finally they had to burst from it. He wouldn’t cry. He would never let them see that. And now his mother was there, pretending to be happy, and Nora, all blubbery hugs, was handing them a thermos for the ride, and Father Tim was saying they’d better be starting. In a minute they’d be gone.

Nick said he had to go to the bathroom and raced into the house, leaving them standing at the car. He walked through the empty rooms, trying to fix them in his memory too, but it felt like someone else’s house. Maybe Father Tim was right. Things passed, whether you wanted them to or not.

He went up to his father’s study and stood at the door. His mother hadn’t taken the desk and it still sat there, just the desk and the blank walls. The window was closed, and in the stale air he thought he could still smell tobacco. His chest hurt again. Why did it have to happen? He stared at the desk. He wouldn’t cry and he wouldn’t do what Father Tim had said. He wouldn’t forget anything. His father was somewhere. But not in the empty room. There was nothing left but a trace of smoke.

He heard his mother calling and went down the stairs to the car. Nora cried, but he got into the back seat, determined not to crack. He wouldn’t even look back. But when the car turned the corner, he couldn’t help himself and swiveled in his seat toward the back window. It was then he realized, trying to remember details, that something was missing. There were no reporters. It was over. There were just the boxes being loaded into a van.

Three years later, in the summer of 1953, after the death of Stalin and the murder of Beria, Walter Kotlar at last gave a press conference in Moscow. In the chess game of the Cold War, the move was meant to dismay the West, and it did, another blow after the disappearance of Burgess and Maclean. Like them, Kotlar denounced Western aggression as a threat to world peace. But his remarks were limited, and he made no reference to the circumstance of his defection. His presence was the story.

Nick had waited so long for his answer that when it came, a grainy newsclip, he felt a numb surprise that it didn’t explain anything after all. It solved a puzzle, but not the one he wanted to solve. His father looked well. There was the expected storm in the papers, the events of 1950 retold as news, and for a day Nick and his mother wondered if their lives would be exploded again. But no one called. The country had moved on. And by that time Nick had a new father and a new name, and their troubles, everything that happened to them, had become just a part of history.