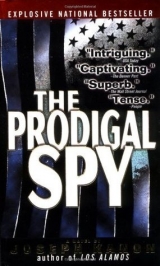

Текст книги "The Prodigal Spy"

Автор книги: Joseph Kanon

Жанры:

Шпионские детективы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 27 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

“Yes, that pink.”

He snorted. “Not far from the tree. Well, not with my agents, you’re not. Don’t expect any help from this office. And keep the Bureau out of it.” Hoover held up a finger. “I mean that. I’m not interested in history.”

And Nick saw suddenly that it was true, that all the stagecraft was there not to trick the future but to keep things going now, attorney general after attorney general, Hoover still at the desk. The only idea he’d ever had was to hold on to his job.

“Then it won’t matter,” he said.

“You know,” Hoover said, more slowly now, “a lot of people come into this office just set on showing me they’re not afraid of me. It’s a thing I’ve noticed. Smart talk. They don’t leave that way.”

“How do they leave?”

“With a little respect for this office and what we’re doing. They find it’s better to be a friend of the Bureau.” The eyes so hard that Nick had to look away.

“Would you tell me something?” he said.

“For your research?” Almost spitting it.

“No, for me. Just one thing. It can’t possibly matter to you anymore.”

Hoover looked up, intrigued.

“Who told you about Rosemary Cochrane? You told Welles, but someone told you.”

“What makes you think I told Welles?”

“Because he told me you did. He didn’t intend to, but he told me.”

Hoover twitched, annoyed. “Well, that’s not what I would call a reliable source. Ken doesn’t know enough to come in out of the rain. Never did. Did a lousy job with your father, too.”

“Despite all the help.”

Hoover said nothing.

“You knew about her. How? It can’t matter anymore.”

“It always matters. That’s Bureau business. We never divulge sources–wouldn’t have them, otherwise.” He paused. “But in this case, since it matters to you.” He glanced up. “It was an anonymous tip. A good one, for a change. We never knew who.”

“Yes, you did,” Nick said.

“You’re sure about that,” Hoover said, toying with him.

“Yes.”

Hoover glanced away. “I don’t remember.”

Nick stood, waiting.

“I don’t think you understand how things work here,” Hoover said, looking back at Nick. “Information, that’s like currency to us. We don’t spend it. We don’t trade for it.”

“Yes, you do.”

For the first time there was a trace of a smile. “But you see, you’re not a friend of the Bureau’s.”

Nick stared at him, stymied.

“Now I’ll ask you something,” Hoover said. “Why you? All those years, and you’re the one he sends for, says he wants to come home. Why not just go to our people in the embassy?”

“Would you trust them? Every embassy has informers. If the Russians had found out—”

“Well, they did, didn’t they?” A shot in the dark.

“If they did, Mr Hoover, then they got it from you. Only the Bureau knew. Is that what you think happened, a leak in the Bureau?”

“No, I do not,” he said, steel again. “We don’t have leaks.”

“You must have had one once. My father had his file.”

Hoover frowned. “Lapierre said you’d seen that,” he said, diverted now to the office mystery. Another witch-hunt, irresistible.

“But he might have got it a while ago. Actually, I never thought the Russians did know. But if they did, that means—”

“I know what it means. And that never occurred to you.”

“No. I thought he committed suicide.”

“With you there? He makes you go to Czechoslovakia so he can kill himself while you’re around.”

“People who commit suicide don’t always make a lot of sense.”

Hoover looked at him, then turned to the window, pretending to be disappointed. “I don’t think you do either,” he said, looking down at Pennsylvania Avenue. “Don’t have too much fun at our expense–it’s not worth it. I’ve been here a long, long time. And I knew your father. I studied your father. You want me to think it was just a pipe dream. Our man didn’t think so. Some pipe dream. Your father knew how things worked. If he wanted to come back, he knew he’d have to buy his way back. But what was he going to buy it with? You’d need a lot of currency to do that.” He turned back and stared at Nick. “And somebody to make the deal. Close, like family.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Nick said, holding his gaze.

“I hate to see good information go to waste, get in the wrong hands. Hate it.” He paused. “Most people find that it makes sense to be a friend to the Bureau.”

“I can’t afford it. It’s too expensive.”

Hoover nodded and moved toward the table behind the desk. “There’s all kinds of information,” he said, and pressed a button on a tape recorder. Nick heard a scratch, then his voice, Molly’s.

“Here’s an idea. Let’s smoke a joint and make love. All night. No microphones.”

“I liked the microphones. Where’d you get the stuff?”

“Well, I did see Richie.”

Hoover clicked it off and looked at him for a reaction.

Not the Alcron, looking up at ceilings. The Plaza, where they were safe.

“Where was the bug?” Nick said, stalling.

“The phone.”

“You can’t use it.”

“No? For two cents I’d set you up, you and your hippie girlfriend. I can do it. For two cents.”

Nick stared at him, the bantam chest and dyed hair, his eyes shining, about to win. The way it worked. “But you won’t,” he said finally. “You can’t afford it either. Larry Warren’s a friend to the Bureau.”

Nick saw the tic, the flesh of Hoover’s cheek quivering as if he’d been slapped.

“Two cents,” Hoover said, machine gun speed again, trying to recover. But the air had gone out of it, his skin now slack with age.

Nick turned away. “Keep it with the lighter, just in case. Can I go now?”

“Think about what I said. Hard. Maybe something will come back to you.”

Nick walked toward the door.

“Don’t push your luck,” Hoover said, wanting the last word. “Not with me. I hear you had a rough time over there. You might learn something from that. How things are.”

Nick turned from the knob and looked at Hoover. “I did learn something. You know, when I walked in here I was afraid of you. The Boss. You want some history? That was Stalin’s nickname too. Just like you. But you’re not that scary. You’re just a guy who likes to go through people’s wastebaskets.” Hoover’s face went blank, amazed. “You know what I learned? Nothing is forever. You think you are. You’re going to be disappointed.”

For a moment Hoover just stood there, seeming paralyzed by the impertinence, then his eyes narrowed. “You’ll change your mind. They always do. It’s better to be a friend.” He walked back toward his desk, pulling himself together. “So I’ll give you something free. As a friend. The Bureau isn’t following you. Maybe we should be, but we’re not. And maybe you’re not as smart as you think you are. Just a little paranoid.”

“Maybe.”

“You see how it works. Now you give me one. I know he talked to you. How else would you know about the lighter?”

Nick smiled and opened the door. “An anonymous tip.”

He walked over to the Mall and sat on a bench watching them build the scaffolding for the rally. Kids in T-shirts and Jesus hair with hammers. Portable toilets. In a few days the buses would pour in. Speeches and peace balloons. All of it happening somewhere else, in the present, while he waited to find someone in the past. Hoover hadn’t dyed his hair then. He’d been a real monster, not a creaky vaudeville turn, hanging on. He’d made Welles, McCarthy, Nixon, all of them. Passing out his currency. Now some were dead and one was in the White House and everyone had moved on to the next thing. Except Nick.

He noticed some men in suits loitering by the construction site. The Bureau, getting ready? He should get up and go home. Which was where? A hotel with a piano player in the lobby. A room in London he couldn’t even remember. He looked up toward Capitol Hill. That wasn’t home either. But he was still living there, on 2nd Street, trying to find his way out. The trouble with history, his father had said, is that you have to live through it. A crime story where everyone did it, without even thinking, as careless as an anonymous tip. And then went on. But what if it stopped, a freeze frame? What if you were the one caught in the picture? Stuck–unless you found the one with his finger on the shutter. Who had told Hoover?

Molly was already at the hotel when he got back. “They said no?” Nick said.

“No. Half-day. Orientation. They jumped at it once I said temp–no health plan.”

“Her department?”

“Well, they rotate. But I told them that’s where I’d done it before, so it should be okay. I start with ties–no sizes, even I can do it. She was doing hats today. I mean, who wears hats anymore? Everybody switches around except for the men selling suits. I suppose you really have to know about suits.”

“What was she like?”

“Nice, but not too nice. She probably thinks I’m going to be a pain. You know, who needs a trainee? But the point is, I can see her no matter where they put me. It’s all open except for the fitting rooms. So.”

“So now we wait.”

“You do.” She grinned. “I’ll be on my feet. And they’re already killing me.” She took her shoes off and lay back on the bed, looking up at the ceiling. “I wonder if she’s in love with him too.”

“He’d be a little long in the tooth now, don’t you think?”

“Oh, men just keep going.” She smiled at him. “At least I hope they do.”

He sat on the bed and began rubbing her feet.

“Mm. What every working girl needs. Brown’s still not back, by the way.”

“You went out there?” Nick said.

“Well, I had the time. Just a drive-by. I was curious. There’s something going on–it doesn’t make sense.”

Nick shook his head. “We should leave the others alone. What if they spot us? We don’t want to complicate things now.”

“I don’t think anyone followed me.”

“No. Hoover said they’re not tailing us.”

“Really? What about the man outside the hotel? He wasn’t just waiting for a cab. I know he wasn’t.”

“That’s what he said. Of course, it wouldn’t be the first time he lied.”

The real waiting began in the morning. Nick stayed at the hotel, afraid he’d miss Molly’s call if he left, unable to read or think about anything else. So close. He played a game with the United Charities list, checking it against the phone book to see who was still alive, still in Washington. The others he could run through the Post obituary files, finally winnowing it down. Some names he could deal with by sight–politicians gone after failed elections, senators old even then, his parents, still together on the list. But there were too many. He might as well be doing crossword puzzles, just passing time. His father had said the reports were irregular. How was it done? Was there a prearranged signal, a call, or did he just stroll into the store, a man shopping on his lunch hour? Nick’s worst fear was that he might appear without their even knowing it, the waiting all for nothing.

The next day, too restless to stay inside, he walked over to 14th Street and circled the building to fix the likely exits in his mind. When he walked into the men’s department, Molly looked up in surprise, then cocked her head toward the blond girl folding sweaters. There were only a few customers. Nick moved slowly past the counters, browsing, familiarizing himself with the floor layout. You could see everything from the fitting rooms. He made his way to the shirt counter, where Molly was waiting, glancing at him nervously.

“Fifteen and a half, thirty-three,” he said, then stopped. Not even his size. When she reached behind her and handed him the shirt, he felt, eerily, that he had crossed some invisible line into his father’s life. Exactly the way it must have been, no one noticing. He fingered the shirt wrapped in plastic. You could slip an envelope underneath. Rosemary could take it, hand you another, ring up the sale, and carry the shirt back to the stockroom. A crime so easy no one would ever see. He realized then that Molly was staring at him, disconcerted.

“I’ll come back,” he said, embarrassed, and walked away.

After that he stayed with the list, not trusting himself to go out. He reread Rosemary’s letter, trying to imagine what her voice had been like. Throaty, maybe, like Molly’s. The hotel room was claustrophobic, so he sat for hours gazing out the window, going over everything that had happened in Prague, some clue he might have missed. He wondered what had happened to Zimmerman, what Anna Masaryk had done with the exit visas. He could see them both vividly and realized that this is what people in prison did–floated out of their cells into some imaginative other life. She had been putting lipstick on when the bellboy brought the setup. Two glasses. Happy to see him.

The phone rang twice before Nick came back to his own room.

“She asked to switch with me Friday. Tomorrow. To do the shirts,” Molly said. “I don’t know if it means anything or not. But why switch? Nick?”

“I’m here.”

“So what do you think?”

He paused, not sure.

“Well, it might be, don’t you think?” Molly said eagerly. “Why don’t you buy yourself a suit tomorrow?”

He tried on several, lingering in front of the mirror with one eye fixed on the shirt counter. Finally, when the salesman became impatient, he picked a blue pinstripe and stood on a raised platform while the tailor measured for alterations. But how long could he string it out? A few men, all of them too young, bought shirts. The blond girl, Barbara, kept looking around as if she were expecting someone, but nothing happened.

When the floor manager told her to go to lunch, Nick followed. A sandwich in a coffee shop, eaten quickly. When she went back to Garfinkel’s, Nick stopped himself at the door, his excuses to go inside exhausted. He went across the street and kept watch from a doorway. Smoking, waiting to meet a friend. Then another corner, a newspaper. The afternoon dragged on. How much longer?

He went back into the store and caught Molly’s eye. A quick shake of her head. He crossed the floor, positioning himself next to ladies’ scarves, then bought some perfume, all the while keeping the men’s department in sight. Almost closing time. Barbara looked at her watch and then toward the door. A missed connection, or just a salesgirl eager to go home?

When the bell rang, Nick’s heart sank. He’d made himself conspicuous and no one had showed. He watched her close the register with Molly, chatting, then had no choice but to follow the other customers out. He waited across the street again and then, on the chance that she was meeting him after work, moved toward the employee entrance. A group of women, talking. He picked out the blond hair easily and began to track it back toward Dupont Circle. Maybe a drink after work? But Barbara, the reliable tenant, went straight home, and when he saw her go through Mrs Baylor’s door he knew the day, with all its nervous expectations, was gone.

“But she asked to switch again,” Molly said later. “Maybe he couldn’t make it for some reason.”

“And maybe she just likes shirts,” Nick said, depressed.

“No, she never asked before. It has to be. Anyway, you could use the clothes.”

The next morning was like the first: sleepwalking past the sales tables, picking through the suits, the clerk puzzled at his being there again but still wanting to make a sale. Nick said he’d try a few on, hoping the salesman would go away, and went into one of the changing rooms. The door was louvered, so that if you bent a little you could see between the slats. Barbara at the shirt counter. But he couldn’t stay here forever, peering out. The clerk had someone else now and was leading him toward the tailor, but he’d knock in a minute, wanting to know if everything was all right. Nick thought suddenly of the station men’s room, the sick feeling as the footsteps came closer.

He was about to give up and open the door when he saw Barbara’s head rise, relieved, recognizing someone. She turned and pulled two shirts off the shelf, ready, then glanced to either side of her to see if the coast was clear as the man’s back came into view. For a second Nick didn’t breathe. The man was picking up a shirt, handing the other back to her, turning slightly as she went to the register. Nick grabbed the slats with his fingers, lightheaded, steadying himself as his stomach heaved. He’d seen the face. A shouting in his head. He opened the door.

“Ah, and how did we like the gray?” the salesman said, but Nick walked by him, one foot in front of the other, as if he were underwater. Moving toward the shirts, a hundred pictures flashing by him, rearranging themselves in place. The same face through the cubicle slats, in a slice, just like the crack at the study door. Molly watching him, her mouth open. And then he was there, behind the familiar shoulders.

“Hello, Larry,” he said.

Chapter 19

“HE TOLD YOU.” They were on a bench in Lafayette Square, across from the Hay-Adams, everything around them drenched in sun, surreal, Larry’s voice as calm as the quiet park. A man feeding birds, a young woman pushing a pram–no one had the slightest idea. Larry had led him here by the arm, guiding him out of the store as if he were a patient, one of those men in Nick’s unit who’d been too near a bomb and had to be helped away.

“No. He never knew,” Nick said, almost whispering, foggy. “Except at the end.” His voice was coming back now. “That’s why he changed his plan that day. He figured out the lighter–that you were the only one who could have taken it. From the study.”

“That was an accident. I must have put it in my pocket. But then I had it—”

“He was going to use you to make the deal for him. Then he realized you were the one person he couldn’t use. He’d have to do it himself.”

“He must have been out of his mind.”

“Yes.”

“Come back. Really, Nick—”

“Are you going to kill me too?”

“Don’t be ridiculous. You’re my son.”

“You killed the other one.” Then, to Larry’s blank expression, “She was pregnant. Rosemary Cochrane. It was yours, wasn’t it?”

Larry was silent. “I didn’t know,” he said finally, past denial.

“Would it have made any difference?”

“No.” He looked away. “It was too dangerous.”

“She wouldn’t have named you. She was in love with you.”

“You can’t trust that,” he said dismissively. “She was just a girl. Then she got–emotional. And she slipped up somehow. They got on to her. It was dangerous. She knew about me.”

“But he didn’t.”

“No. But he was going to crack. I saw it that night.” He glanced over. “When you were spying on us.”

“I didn’t understand anything.”

Larry sighed. “Well, neither did Walter. That was the problem. He didn’t understand how serious it was. He thought–I don’t know what the hell he thought. Buy them off with a name and live happily ever after? It doesn’t work that way. Once you start, you go to the end. And what name? He only had Schulman.”

“Who recruited him.”

Larry looked back, surprised. “That’s right. And me. At Penn. The one point of connection. I couldn’t risk that. If he’d given them Schulman, it might have led them to me.” He wrinkled his face. “The way things work out. I was the one who suggested he try Walter. He was always looking for prospects. I told him Walter might be promising material. But he turned out to be the weak link. You see that, don’t you? He might have brought the whole thing down.”

Nick looked at him, incredulous. Was he being asked to agree?

“They had to protect me. I was in the White House. We’d never had a chance like that.”

“Why didn’t you just kill him too?”

Larry looked at him with an indulgent expression. “Is that what you think of us? Of course we didn’t kill him. Anyway, you take care of your own, unless there’s no other choice. That would have been a foolish risk to run. Two deaths? No one would have believed the other was suicide. There’d be no end to it.”

“The police didn’t believe it anyway. You made sure of that. With the lighter.”

“No, I was making sure of him. I wasn’t sure he’d go. Walter was unpredictable.” He paused. “He had reasons to stay. He might have thought he could tough it out, not accept our invitation.”

“But not if he thought he’d be accused of murder. Then he’d have to go.”

“Well, it never came to that. It was just a precaution. He did go.”

“Convenient for you.”

“Convenient for everybody. Except old Ken Welles, I suppose, but that couldn’t be helped. Oh, you think we wanted him stopped? No–he was useful. He was so busy looking for Commies in all the wrong places, nobody thought to look in the right ones. Loyalty oaths for schoolteachers –Christ. But even a fool gets lucky once.”

“You had Hoover looking too.”

“Well, I didn’t want him looking at me. All I had to do was suggest that Walter must have been tipped off by someone in the Bureau and he was off. Catching his rats.” He stopped. “I never wanted to hurt Walter.”

“You killed him.”

“We got him out. It was the best we could do. He had a life there, you said so yourself. We had to do it.”

“Not then. Now. You killed him. Or had him killed.”

“You don’t know that.”

“We’re sitting here, aren’t we? How do you think I got to you?”

Larry looked up at him, serious. “How did you?”

“First tell me why.”

“Why. What else could we do? Coming back. That could only mean one thing. He found out. I don’t know how–we were careful about that. All those years. I knew how he’d react. He’d make it personal.”

“It was personal.”

“No. I was just another agent.”

“Who took his wife. And set him up for a murder charge. And got rid of him to cover your own ass. You ruined his life, Larry. What do you call personal?” Larry turned away. “Why did you have to kill him? He was never going to get out–you know that.”

“He didn’t have to get out. Once he knew, he could have told anybody. A journalist. The spooks at the embassy. He wasn’t safe if he knew.” He paused. “Given everything.”

“But he didn’t know, Larry. Not until the end. You had him killed for nothing.”

“What do you want me to say, Nick? I’m sorry? It’s a death wish, to want to defect. There’s only one way to do it. If he didn’t know about me, then he knew others. He was going to turn them. This isn’t school. What did you expect them to do?”

“Once you told them.”

“Yes, once I told them,” he said impatiently. “Of course I told them. You don’t wait. We’re all at risk when somebody defects. He had to be stopped before anything got out. It had to die with him.”

“It didn’t,” Nick said quietly. “He told me. That’s what led me to you. Names. Her, your new friend. You ought to change your pattern, Larry. You made it easy. It didn’t die with him.”

Larry crossed his legs and looked down at his trousers, picking at the fabric, seemingly at a loss. “Well, that creates a little situation, doesn’t it?”

“Yes. You’ll have to kill me too.”

“Does anyone know?” Larry said.

“Just me. Once I’m gone, you’re safe.”

“I didn’t mean that. I was thinking of you. Are you sure? What about that girl?”

“No,” Nick lied. “Just me. You’d be safe.”

“Don’t talk crazy. Kill you.” He turned to Nick, his eyes suddenly old and unguarded. “You’re all I care about. Don’t you know that?”

Nick felt a tremor, another shock to the system. Not a lie. His boy, the unexpected thing in his life, a knot too tangled to untie. Nick looked away.

“You should have been more careful in Prague then,” he said. “I almost didn’t make it. Or were you going to get me out of that one too?”

“But I didn’t know you were there,” Larry said, reaching over and putting his hand on Nick’s arm. “I didn’t know. You have to believe that. I would never involve you. Nobody said you were there.”

“Didn’t Brown tell you?”

“Brown?”

“One of yours. Over in Justice—”

Larry held up his hand. “Don’t. I’m not supposed to know. It’s safer.”

“Then who did?”

“Hoover. He called. He had a report from one of his legats saying that Walter was planning to come back. Did I know anything about it? I suppose he thought I might, because of your mother. He never said anything about you. Why would I even think it? It was a damn fool thing for Walter to do, involving you. What was in his head? You don’t do that.”

“He trusted me.”

“He didn’t even know you. I was there, not him. No matter what you think of me now, that part’s still true. He wasn’t there. I was. I gave you everything.”

Nick looked at him, amazed. “No,” he said. “You took everything.”

A pause. Then Larry looked down at his watch. “Well, this isn’t getting us anywhere. And I have a meeting.” He looked up. “You’re being sentimental. Walter was a damn fool. But you’re all right, that’s the main thing.”

“You have a meeting?” Nick said. Was he just going to walk away?

“Yes, at the White House. Walk over with me.” He stood up.

“Do you really think I’m going to let you do that?”

Larry raised his eyebrows, genuinely puzzled.

Nick got up, facing him. “I know everything you’ve done. Your code name. What happened at the hotel. How you report. All of it.”

“You’ll make an awful mess trying to prove it.”

“I can do it. I have documents. He gave them to me.”

“Ah,” Larry said, looking away. “Then I guess I’m in your hands. You might say we’re in each other’s hands. Sort of a protection racket.”

“I’m not in your hands.”

“Well, a minute ago you said I was going to kill you. Which I’m not, of course. But you’re not going to do anything either. What did you have in mind? Turning me in? Your own father? I don’t think so. You know, Nick, you’re more like me than you think. We’re both pragmatists. We take the world as it comes. You just got thrown a curve, that’s all. But don’t do anything foolish. What’s in it for you? Patriotism? Not very pragmatic.”

“You bastard. Listen to me—”

“No, you listen to me. Calmly. We’re going to walk out of the square, and in a few minutes I’m going to sit down at a table and listen to fools and crooks tell me how they want to run the world. I’ve been listening to them for thirty years, different crooks, same fools. But I’m at the end. This is my last job. After that I won’t be a threat to anybody, least of all the country. That you think you care so much about. It’s over. Walter told you things he had no right to tell. You’re lucky, no one knows except me. So you come back playing detective, all fired up to change the world. Just like Walter used to be. But you’re not going to change it. Nobody does. What you might do is cause a scandal that would embarrass the Government–not a bad thing in itself, given who they are. But it’ll be a lot worse for us. It would kill your mother.”

“No, it wouldn’t.”

“And what about you? You know what it would mean. Do you want to go through all that again? I’m not doing anything more than what Walter did. You want to make him a saint, that’s your business, but don’t drag the rest of us down trying. Do you think anybody wants to know? That time is over. You think Nixon wants his old Red-baiting days brought up again? Mr Statesman? Hell, the only one who still cares at all is Hoover, and he’s been nuts for years. No one wants to know. Who would you be doing it for?”

“For me.”

“For you. Why? Settling someone else’s scores. And you’d still have to prove it. I don’t know what you think you have – is it really enough? I’d have to fight you, and I’m good, I’ve been doing it for a long time. I don’t want to fight you, Nick. You’re my son. You are, you know. We’d be killing each other. Like scorpions. We’d both go down.”

“You killed someone, Larry. Doesn’t that mean anything to you?”

“Listen, Nick, I’m going to a meeting now with men who are killing thousands, and people think they’re heroes. I didn’t make the world. At least I did it to protect myself – that’s the oldest instinct in the book. What’s their excuse? Come on, walk with me. I’ll be late.”

Numbly Nick fell in step at his side. “I don’t care about them, Larry. You killed him.”

“He killed himself, Nick. He killed himself the moment he decided to turn. Those are the rules. They’d do the same thing to me–or you. Be smart. Let’s all just retire in peace. Think of your mother. You don’t want to do this to her.”

“Look what you’ve done to her.”

“I hope I’ve made her happy.” He turned. “She can’t know about this.”

“What’s the difference? A wife can’t testify against her husband.” Nick stopped. “Is that why you married her?”

“Of course not. I love your mother. I always have.”

“You’re a liar, Larry. You don’t even know her.”

“I’m not going to argue with you, Nick. I did my best, that’s all I can say.”

“You even lie to yourself.”

“Well, we all do that.” They stopped near the entrance to the White House, across the lawn behind the tall railings. Barriers along the street to keep protestors away. Larry waved to one of the guards and turned. “But I’m not lying to you. There’s no advantage here. Be smart.”

“Like you. Maybe I’m one of the fools. Are any of them smart, or are you the only one?” Nick cocked his head toward the gate, where a black limousine was pulling onto the driveway.

“Well, they’re not very bright,” Larry said. “Anyway, it won’t be much longer. I’ll be out this fall. Would you like me to resign sooner? Would that ease your conscience?”

Making a deal, the way he always did. Sure of himself. Nick looked at him, the familiar face suddenly inexplicable. “Tell me. Why did you do it?”

“I thought I explained—”

“No. It. Are you a Communist? I mean, do you believe in it?”

“I used to. I thought it would fix things.”

“But not anymore.”

“I’m too old to believe you can fix things.”

“Then why did you keep going?”

“Well, you have to.” An easy answer, but then he stopped, thinking. “I don’t know if you’d understand. It was the stakes. It was–you’d sit at a table, in there.” He jabbed his thumb toward the gate. “You’d sit there while they all talked, and none of them knew .”

“That you were betraying them.”

“That you had the secret. This big secret. None of them knew.” He shrugged. “But that’s all over now. My son’s going to insist I retire.” He smiled his old Van Johnson smile and turned to the gate. “Call me after lunch.”

“But—” Nick reached out to stop him, but Larry had already moved out of reach, so that Nick’s arm just hung in the air, as if he were holding a gun. Then slowly he dropped it, unable to pull the trigger.

Molly was still at the store, waiting.

“I didn’t know what else to do,” she said. “What happened?”

“Where’s the girl?”

“She split. But I got this.” She held up the envelope. “She was too freaked to argue. Just ran.”

“Did you look?”

Molly nodded. “What we’re going to say in Paris. Talk about a stacked deck. If this doesn’t put him away, nothing will. What happened? No more than what your father did–another lie. He was prolonging the war.