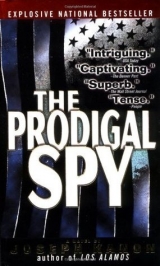

Текст книги "The Prodigal Spy"

Автор книги: Joseph Kanon

Жанры:

Шпионские детективы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

Nick followed him out of the room, then past the walls of impaled martyrs. “But we have to talk.”

“We will. Later.”

They were out on the cobblestoned square.

“Don’t worry. I’ll tell you exactly what to say.” He reached into his breast pocket and drew out an envelope.

“I can’t carry anything out,” Nick said, flustered, physically drawing away from it.

His father looked at him, then smiled, holding out the envelope. “No. These are tickets, for tonight.”

“Oh.”

“Benny Goodman. They’re hard to get. Everyone wants to see Benny. Nothing changes, you see.”

Nick said nothing, feeling teased. An evening out.

“I didn’t know he was still alive,” he said finally. They were crossing the square toward the Czernin Palace. There were no cars.

“Oh yes. He’s very popular here–we’re a little behind. His goodwill tour. You’ll enjoy it. We can eat afterward.”

Nick stopped, annoyed. “Look, I need to talk to you.”

“I know,” his father said, putting a hand on his arm. “You’re worried. There’s no need. You’ll see.” He continued walking. “This is where Masaryk was killed, by the way.” He indicated the high palace walls. “In the interior courtyard.”

“They found the lighter,” Nick said suddenly.

“What lighter?” his father said, still walking.

“Yours. The one Mom gave you.”

Now he stopped, his face bewildered. “What are you talking about?”

“They found it in the hotel room. That night. It’s in the police report.”

His father frowned, as if he’d misunderstood, then looked away, thinking to himself. Nick watched him as he stared at the ground, apparently at a loss. Was he thinking of what to say?

“That’s interesting,” he said finally, but not to Nick, working instead on some interior puzzle.

“Is that all you can say?” Nick said, thrown by his response.

“But how is that possible?” his father said, again to himself.

“That’s what I’m asking you.”

“A police report? But it’s a mistake. The FBI handled the case, not the police.” He paused, still thinking. “Of course they would have been called first. At the hotel. But the FBI took it over. It was a Bureau case always. There’s nothing like that in their file.”

“How do you know?”

His father looked up at him. “Because I’ve seen it. Don’t you think I would have remembered that? Why would they leave it out?” He shook his head. “It’s a mistake.”

“No,” Nick said. But what made him so sure? “It’s in the police report. Don’t you understand what I’m saying? You can’t go back. They know.”

“Know what?” He looked at him again. “Oh, I see. I left it there. After I—” He paused, a new idea. “Is that what you think?”

“You tell me.”

“Nick, how could I have left it? I already told you—”

“You don’t tell me anything. Except what you want me to hear.”

“I’ll tell you again,” his father said quietly. “I wasn’t there.”

“Then how do you explain this?”

“I can’t.” He looked down. “I don’t know what it means. I have to think.”

“Let me know what you come up with. But maybe you should think twice about traveling. They think you were there. The statute of limitations doesn’t run out on this.”

His father touched Nick’s elbow. “You know who was there. We’ll find him. Trust me.” The cord again, pulled tighter.

“No questions asked,” Nick said. “I’m not supposed to know what’s going on. You said last night you had something valuable. What? Or am I not supposed to know that either?”

“It would be better.”

“No. I need to know what you’re doing. What I’m doing. You need to trust me. I’m not just a messenger.”

“No,” his father said. “You’re the key to everything.”

Nick stared at him.

“Listen to me, Nick. They’re not going to accuse me of anything. Not some old crime.” He glanced up. “Which I didn’t commit. They’re going to ask for me.”

“They’re what?”

“How else do you think this can work? A rescue mission to smuggle me out? I’m not worth an international incident. The Americans would never do that. It has to be a trade, a quiet trade. I can’t escape–think what that would mean for Anna. I have to go legally. A plane from Ruzyně. With the comrades waving.”

“What’s the trade?”

“They can offer Pentiakowsky, a prize catch. For one broken-down defector. Do you think Moscow would resist such a deal?”

“Why would they do that?” Nick said, trying to follow the thread. “Why would they ask for you in the first place?”

“Because you asked. You and your mother. A humanitarian request. You came to see me–I know, all this secrecy, but that’s only for now, until we’re ready. Once the arrangements start, it’s in their interest to protect me. They’ll have to know you were here so the story makes sense. There’s always the personal element, even in politics. You were shocked by what you saw. My health. I need an operation. That’s true, by the way, I do. They know that. I can’t get it here. So the trip would have a certain appeal, even to a dedicated old socialist. How we cling to life. So you appealed to your father, the other one. A man close to the President.”

“What?”

“Yes, to Larry. No one else. He can make the deal, arrange things. I’ll tell you what to say.”

The surprise of it made Nick feel giddy, as if a missed step were pitching him farther down. “Larry,” he said, trying to catch himself. “Why Larry?”

“Because he can do it. Arrange things. And he’ll believe you. He’ll know it’s not a trick.”

“No,” Nick said quickly, not wanting to hear the rest. “You don’t know what you’re asking. He can’t.” Isn’t it enough to involve me? He saw the mad plan spreading like a stain, touching everybody.

“I know what I’m asking. Do you think I would ask him if I didn’t have to? He took my family.” An edge, finally, in his calm voice, a bitterness not quite put away. “But now that’s an advantage. He owes me this much. One favor. He’ll do it.” He paused. “He’ll do it for you.”

And I’ll do it for you. A link snapping shut in a chain. Every link already assigned.

“It’s the right story,” his father continued, not seeing Nick’s face fall. “Pentiakowsky for an old spy? Never. But I’m not just an old spy. I have friends in high places.” He stopped. “A son in high places. Lucky for me, but even luckier for Moscow. To get Pentiakowsky back for a political favor? A stupid trade–but Americans can be stupid that way. Sentimental.” He looked at Nick. “They’ll believe you. Not just a messenger, you see. There is no story without you.”

Nick looked at the ground, feeling his chest tighten, his breath grow short. “You have it all worked out,” he said, thinking, all of us, he’ll use all of us. “What makes you think Larry will do it?”

“He wouldn’t. He’s not sentimental. Or his boss. It’s only the story, Nick. For Moscow. The truth is that I have to give them something.”

“Something valuable.”

His father nodded. “More valuable than Pentiakowsky. Then they’ll do it. It’s the only way.”

“Then why would Moscow let you go?”

“They don’t know I have it. They’ll be suspicious–that’s their nature–but they won’t know. There’s no trace–I’ve been careful. No one knows. Only you.”

“Not yet.”

“No, not yet.”

Nick waited, his silence an unspoken demand. His father looked back toward the open square, then wet his lips, an old man’s nervous gesture.

“I’m going to give them what they always wanted. Names. In America. I have a list. And documents.” He saw the dismay in Nick’s face. “I have to pay, Nick. You don’t get a fatted calf, not in real life. What else do I have?”

“And what happens to them, the people on your list?”

His father shrugged. “They’ll be replaced. Then it begins all over again. But meanwhile—”

“You get Silver,” Nick finished.

His father shook his head. “Not yet. But they can lead me to him. One of them. There’s a pattern, you see. People don’t change. There’s always a pattern if you can find it.”

“And you did.”

“I think so.” His father looked at him carefully, then said, “You disapprove.”

“They’re your people.”

“My people,” he said, almost scornfully. “Yes. Agents expect it, you know, sooner or later. Somebody always gives it away. What do you want me to say, Nick? That it’s not a dirty business?” He looked away. “It never seems so in the beginning. You just think you’re doing the right thing, like a soldier. But in the end—”

His voice drifted and Nick followed it down the gray street, unable to look at him.

“So you do want me to take something,” he said quietly. “The documents.”

“No, of course not. I would never put you at risk. I told you that. Anyway, they’re a passport for me. I take them.”

“Then how will Larry know that all this is for real?”

His father looked at him curiously, as if Nick hadn’t been listening. “Because it’s you. He’ll believe you.”

Nick’s chest, already tight, seemed to clench further. Not just a messenger.

“You see how important–that no one know. Just the fact of it, that such a list exists, is dangerous for me.” His father paused. “Now you.”

“Are you trying to frighten me?”

“No, protect you. I’ll tell you what to say when you leave, not before. Just in case. Who Larry should contact. No one else, just the principals. He must understand this. Everyone talks. On both sides. But if we move quickly—”

“Before your names can run for cover, you mean,” Nick said. “Your chips.”

“No,” he said, cut by the edge in Nick’s voice. “Before the leaks. There are always leaks. Before he knows. I wouldn’t be safe here.”

“You won’t be safe there either. They’ll know it was you.”

“That depends. Sometimes it’s better to let people stay in place for a while.”

“To watch them.”

His father nodded. “Or turn them. It’s been known to happen.”

“Come play on our side,” Nick said evenly. “Your choice.”

“Nick—”

“Do you know them, the people you’re going to sell?”

“No.”

“That must make it easier.”

“Yes, it does.” He looked at Nick steadily. “Your scruples are misplaced,” he said, his voice cool, a kind of reprimand. Then, backing down, “Nick, it’s the only way.” He turned, wanting to bring it to an end. “Walk with me. I’ll be late.”

Nick stared at his back, the familiar hunch of his shoulders, then took a step, pulled along.

“And what if they don’t leave them in place? Then what happens?”

“What you’d expect. The usual scurrying.”

“I mean, what happens to you? Your life wouldn’t be worth—”

“Like the old Comintern days? Send someone out to deal with me? Not anymore. I’ll be all right, once I’m there.”

“And if you’re wrong?”

He smiled a little. “Never bet against yourself, Nick.” Nick glanced up, recognizing it, his old rule of thumb, when they played cards at the cabin. “That sort of thing’s a little old-fashioned, even for the comrades. I’ll be all right, if we move quickly.”

“How quickly? Larry’s in Paris. You know, at the peace talks. He won’t be able to just drop everything.”

“To negotiate for me? Yes, he will. Nobody wants peace. But they’ll want this.”

I don’t want it, Nick thought, so clearly that for a second it seemed he’d said it out loud. But his father’s face, eager, full of plans, registered nothing, and Nick looked away before it could show on his own, the one betrayal his father did not expect. And was it true? Maybe it would be different later, when it was over. Maybe it was this he didn’t want, the plotting and covered tracks, looking over his shoulder, the tired city, gray, expecting the worst.

“Then why wait?” he said suddenly, an escape hatch. “I could go this afternoon.”

“This afternoon?” His father turned to him. “So soon.”

“What’s the difference? Nobody knows I’m here anyway.”

“But they will later. They’ll check. Visa dates. The hotel. It has to look right. It wouldn’t make sense, your coming for a day. That’s not a visit.” He stopped. “Besides, I don’t want you to leave.”

“But the sooner we—”

“Just in case.”

“In case what?”

“In case.”

“Don’t bet against yourself,” Nick said,

“No. But sometimes—” He paused again. “In case it goes wrong,” he finished. “At least we have this time.” He put his hand on Nick’s shoulder. “It’s not so long for a visit. I’ll show you things.” A weekend parent, offering treats.

Nick nodded, embarrassed. How could he go?

But before he could say anything else, make an excuse that would play, he saw his father look past him. He withdrew his hand, alert.

“Valter, jak se máte?”

Nick turned.

“Anna,” his father said, but it was another Anna, broader and short, slightly out of breath from climbing the hill. She said something in Czech, but his father answered in English, “No, we have ten minutes. I’ll walk with you. An American,” he said, nodding toward Nick, an explanation for the English. “I was showing him the way to the Loreto.”

“Dobre odpoledne,” Nick said, offering his hand. “Nick Warren.”

“How do you do? Anna Masaryk.”

“Masaryk?”

“My uncle,” she said automatically, smiling a little at his surprise.

For a second he was jarred, as if she had stepped out of history, straight from the death scene in the Czernin courtyard over the wall. But she was no older than his father, someone you could meet in the street.

“You heard they took Miloš‘s book?” she said to his father.

“Now it begins all over again. How many years this time? All that work.”

“Maybe he kept a copy.”

“What difference? They’ll never allow it now. They don’t want us to know.”

“You know,” his father said, consoling.

“Me? I always knew. But to prove it–they’ll never allow it. They’re afraid of the truth.” She caught Nick’s glance and said, “Excuse me. You’re visiting Prague?” Then Nick saw her look quickly at his father and back again, as if there were something she didn’t understand. Had she noticed the resemblance?

“He’s just been to the Národní Gallery,” his father said before he could answer. “Now the Loreto.” A tourist.

“Ah, yes. There’s a very good Goya. I hope you saw it.”

Nick nodded, hoping he wouldn’t have to describe it. What Goya? Were they going to talk about art?

“Of course, the best are in the Prado. But this is very good. It’s lucky that we have one.”

“Perhaps one day you’ll see the others,” Nick said. “In Madrid.”

The woman looked at him wryly. “I doubt it. It’s not allowed, to go there.”

“Oh,” Nick said, stumbling. “Well, perhaps when things are looser again.”

“It was never allowed. Not since ‘37.”

“Czechoslovakia doesn’t recognize Spain,” his father said, helping. “It’s still considered a Fascist state.”

“Oh,” said Nick, feeling awkward. Another wrong turning in the maze. The old categories, still current, like Masaryk’s death. Everything was yesterday here. No one had moved on. “I’m sorry.”

“So am I,” Anna said. “For the Goyas. You’re staying in Prague long?”

“No, only a few days.”

“Perhaps you would come to tea. If you have time.”

A casual invitation, to a stranger in the street?

“Yes, if I can,” Nick said vaguely, ducking it.

“Valter, you bring him. I never see you anymore. We’ll have a salon.” Was she trying to find out if they knew each other? “It’s good to speak English,” she said to Nick. “You can tell me about the new books. I like to keep up, but it’s so difficult now. Well, we’ll be late. Tomorrow then, if you can. Valentinská Street. It’s in the book. But of course Valter knows.” She took his father’s arm.

“Goodbye,” his father said, shaking Nick’s hand, acquaintances. “I hope you enjoy the Loreto.”

Nick looked at him, waiting for some sign, but his father avoided eye contact and moved off with her, an old couple on their way to a funeral. They reached the corner, and then his father stopped and walked back.

“I told her I forgot to ask your hotel,” he said quickly. “There’s something–the police report. How did you see it?”

Well, how? “A friend got it for me,” Nick said.

His father nodded to himself, thinking. “Was it a copy? You know, a carbon?”

“I don’t remember. Why?”

“They turned everything over to the Bureau. But if they kept a copy, that would explain it. Why they have it.”

“Does it matter? It’s there.”

“But not in the Bureau file. It doesn’t make sense.” He shook his head. “If they found the lighter, what happened to it? It would have been evidence, something like that. So why didn’t they use it?”

“You were gone.” Nick looked at him. “Maybe they will.”

“They still have it?”

Did they? “I don’t know. All I know is they found it. Or said they did.”

“In the hotel room,” his father said to himself. “My lighter.”

“Yes. The one with your initials.”

“But how did it get there?” he said, frustrated, like someone searching for his glasses.

“Well, that’s the question.”

“Yes,” his father said slowly, preoccupied again. “If I could remember—” His eyes narrowed in concentration, lost in his puzzle.

Over his shoulder, Nick saw Anna Masaryk still waiting on the corner. “I’m staying at the Alcron,” he said.

His father glanced up, then nodded and turned without a word, the way old people hang up the phone without saying goodbye, their part of the conversation finished. Nick watched him go, his head bent in thought, until Anna called something to hurry him and he was back in his Czech life, offering her his arm, almost courtly. Then they turned the corner and Nick was alone.

Now what? Unexpectedly, he had the afternoon. But he didn’t want to see anything. Not the Loreto and its famous chimes. He wanted it to be over. He stared down the empty street.

When he heard the footsteps behind him, he froze. Had someone been watching? The steps grew nearer, then passed–a man in a long winter coat, glancing at Nick out of the corner of his eye. He stopped a little farther along and turned, and Nick waited for him to speak, but instead he whistled, and then Nick felt the dog sniffing at his feet. The man said something, presumably apologizing for the dog, then called and began to walk again, looking back once over his shoulder, suspicious. Nick smiled to himself, relieved. What if everything were just as it seemed? A man with a dog. A friendly invitation to tea. Maybe she did like to talk about books, ordinary after all, just a dumpy woman with a magical name. Maybe they were all what they seemed here. Except his father.

He turned down the hill, toward the Malá Strana, replaying the conversation in his head. Easier not to know them. Was he any different? He remembered them shooting blindly into the jungle, everyone in his platoon, ten minutes of random fire. And then the odd stillness afterward, no sound at all, his ears still ringing. You couldn’t trust yourself there either, all of your senses on alert. A twig snapping was enough to set them off. They were lucky that day, no snipers when they located the bodies. One had been shot in the face, his jaw blown open, hanging slack with blood and pieces of bone, and Nick had stared at him, wondering if he had done it. There was supposed to be a connection, the thud of your bullet hitting a body, maybe a scream, but he hadn’t heard anything over the noise of the fire. Some actually claimed victims, like pilots after a dogfight, but they were lying. No one knew. It was easier. Later, in his safe job at the base, he walked around the airstrip with a clipboard, taking inventory on the shipments, and he would see the body bags lined up for the flight home, plastic, like garbage bags, held together with tape. He checked his list, then handed in the manifest and went for a beer. That easy, if you didn’t know them.

He stopped for a minute on the street near some scaffolding where workmen were replastering an old melon-colored facade, and he realized he was sweating. When you started thinking about it, all of it came back, even the heat.

He followed the streets downhill, zigzagging as if he were shaking off a tail, a real spy game, so that when he reached the river he saw that he had overshot the Charles Bridge. It was warmer near the water, the trees in late bloom, and he stood for a few minutes looking at the city, couples huddled on benches, trams, everything ordinary. He started walking downstream toward the next bridge. Could a voice be the same if it lied? What did you trust, a muddled story full of loose ends, or an old man’s hand, the same touch, unmistakable. He stopped to light a cigarette, leaning against a tree. It was when he looked up, blowing smoke, that he saw her on the bridge.

She was standing with a man, talking down at the water, and Nick, startled, moved further behind the tree. Who did she know here? His anger surprised him, a jealousy that went through him like a quick flash of light. Jiří, whom she wasn’t going to see again. When had she arranged it? This morning while he was still asleep, drunk with sex? Nick leaned forward to see what he looked like. But he was ordinary too, his body hidden in a raincoat, his face down, a head full of brown hair. Anybody. But they’d been to bed, making private sounds, holding each other afterward. Until he’d moved on, feckless. Why see him again?

Now they seemed to be arguing, Molly shaking her head. He put his hand on her and she brushed it away. He took her by the arms, turning her toward him, saying something, but she broke away, stepping backward, and Nick realized suddenly that he had got it wrong. Not a meeting she’d wanted. She shook her head again, and Nick could imagine her refusal. No. There’s someone else. He felt a flush, possessive. There was someone else now. Was she as surprised as he had been? Maybe she was tying up her own loose ends, sure now that it had happened. The one thing you could trust. Eyes deceived, not bodies. When he had been inside her, he had felt it, a different touch, just as unmistakable.

Jiří was talking again, and Nick saw her nodding, not looking at him. Then he leaned over and kissed her on the cheek, a goodbye, and this time she didn’t resist it, letting his mouth stay next to her until he was finished and turned away. Nick saw him reach the end of the bridge and dodge across the street, not even a wave back, and felt in spite of himself a last prick of jealousy. Just an old boyfriend, but still a part of her he would never know.

He had moved away from the tree, but she continued staring at the river, absorbed, and even when she looked up her eyes went past him, not seeing what she didn’t expect. Was she thinking about what to say to him later? I saw Jiří. He imagined her voice, breezy and matter-of-fact. I mean, I was curious. Wouldn’t you be? But he’s just the same. Her face, however, was somber, not jaunty at all, and in a minute she looked at her watch and walked away. Should he follow her? There was still the afternoon. But by the time he reached the bridge she was already gone, getting on a tram, her secret safe.

She was gone for hours. He lay on the bed waiting, listening to the maids pushing their carts in the hall, gossiping in Czech.

“You’re back,” she said when she opened the door, surprised. “What happened?”

“He had to go to a funeral.”

“Oh. I wish I’d known,” she said easily. “We could have spent the day together.”

He looked at her. She wasn’t going to say a word. Why not? “Where did you go?”

“The usual. Old Town Square, the clocktower.” Not a word.

She held up a Tuzex bag. “Shopping. I got something for your father. Rémy, no less. Not cheap, either, even with dollars.”

“That’s the last thing he needs.”

“I know, but it’s what he’ll want.”

“That was nice.”

“We didn’t take anything yesterday. You know, for a house present. So I figured—” She smiled at him. “I’m a well-brought-up girl.”

“You could have fooled me.”

She grinned. “Yeah. Well.”

“So you’ve been busy.”

“A little bee. What about you? Have you been here all day?”

“No. I took a walk. Down by the river.”

He watched, expecting to see her hesitate, but she was fishing for something in her bag. Not a nicker. “Look what else I got.” She held up tickets. “Laterna Magika. The hit of the Czech pavilion.”

“The Czech what?”

“You know, at Expo, in Montreal. Don’t be dense. Everybody’s heard of them. We can’t go without seeing Laterna Magika.”

“Yes, we can.”

“No, really, they’re good. I promise you. Don’t you like mimes?”

“I didn’t mean that.” He reached into his shirt pocket for the other tickets. “Benny Goodman. My father got them.”

“You’re kidding.”

“He’s very big here. So I’m told.”

She sat next to him on the bed, taking the tickets. “What time? Maybe we can go after. Anna looks like the early-to-bed type.” She slipped the tickets onto the bed. “Okay, no Magic Lantern. He’s full of little surprises, isn’t he?”

“All the time.”

“What happened today?”

“Nothing. That was the surprise. We didn’t even get to talk.”

“So do you want to go out? Do something?”

“No.”

“Nothing?” She leaned over him. “We have the afternoon.”

“Let me think about it.”

“I only do it once, you know.”

“What?”

“Seduce you. After that you have to ask.”

He looked at her. What had she really said on the bridge?

“So ask,” she said, bending to him.

When he reached up to her he was sure again, the feel of her skin as familiar now as his own.

Chapter 11

IT WAS LATE when they woke up, the bed tangled again from lovemaking, and they had to hurry to dress. The concert hall was nearby, in the New Town, and it seemed his father was right–the bright doorways were crammed with people, a mix of middle-aged suits and young people in jeans. Everybody loved Benny. Prague, usually so reserved, almost sullen, had turned noisy and eager. Inside, people shouted to each other over the crush, passing beers along from the lobby bar, and Nick wondered if the high spirits themselves were a kind of defiance, if simply listening to American jazz, even thirty-year-old jazz, had become a political act. But the mood, whatever its source, was contagious, and for the first time he began to look forward to the evening, ready for a good time.

His father and Anna were already in their seats, looking slightly frumpy in the younger crowd. Why such a public meeting, where everyone could see? Or was this part of the plan too, something that could be verified later? Anna was friendly, pleased to see them, but his father seemed preoccupied, as if he already regretted having come, bothered by the noise. When the lights blinked on and off, no one paid any attention, still talking in the aisles. Then the curtains opened on the band playing ‘Let’s Dance’ and there was a roar of recognition applause and a scrambling for seats. An emcee appeared at the mike, speaking Czech, then Benny in English saying how happy he was to be here, then the opening notes of ‘Don’t Be That Way’, more applause, and the evening, in this unlikely place, began to swing.

The music was wonderful. It was the standard program–next the ‘King Porter Stomp’–but the audience made it seem fresh, their enthusiasm flowing up to the band with such force that Nick saw some of the sidemen grin, bending into their instruments to send it back. “You Turned the Tables on Me‘, with its funny, innocent lyrics. How many of them knew what the words meant? But the music, just as they always said, was its own language, and the audience was answering it, some actually tapping their feet, squirming in their seats to the beat. Nick thought they might leap up to dance, and he saw that in the back of the hall, where the bar was, some of them had. Upstairs in the ring of boxes there were men in bulky suits, Party bureaucrats, their wives fat and shining with costume jewelry, but the crowd on the floor ignored them. There were no uniforms anywhere. Just the music, an official time-out. ”Elmer’s Tune’, where the gander meandered. American music, the happiness of it, as much a part of him as childhood stories. He smiled at Molly, who was drumming her fingers.

When Goodman started the clarinet lick of ‘When It’s Sleepy Time Down South’, the notes jetting out like liquid, he turned to his father. Nick expected to see his face soft with nostalgia, but it was cramped, white, and he realized that his father hadn’t been preoccupied but worried. Even the music couldn’t reach him, wherever he was. Nick looked at him for a second, wondering what was wrong, then made himself turn back. Don’t ruin it. He’d find out later. Now they were here, not in some troubled past, not even anymore in Prague.

There was an intermission after ‘Avalon’ and he went with Molly to the bar, his father staying behind, sitting it out. The lobby was filled with smoke and spilled beer, and the crowd was even more energetic than before, loud with drink. It took a while to get the beers, then a few more minutes to find Molly. She was standing near the door, her back to him, talking to someone. For a moment Nick hesitated. Jiří again? Then she moved slightly and he saw that it was Marty Bielak. Why not? It was his music too.

“Hello,” Bielak said. “Enjoying it?”

I was, Nick wanted to say, but just nodded, handing Molly her glass.

“Of course, I remember the Meadowbrook,” Bielak said. “Before your time. Helen Ward was the vocalist then. And the Long Island Casino. That was something.”

Nick tried to imagine him young, skinny, with a date by the bandstand, raring to go.

“The good old days,” Nick said.

Bielak glanced at him. “Well, the music was good. Maybe not the days.” And then, wanting to be pleasant, “It was another time. Everybody danced. It was always dance music, you know. Not for sitting. To think I’d be here in a concert hall—”

“In Prague,” Nick finished.

“Yes, in Prague. But the music doesn’t change.”

The lights flashed, the signal to return.

“Well, it’s good you could come,” Bielak said. “A taste of home, eh?”

Did he really think this is what they still danced to? An exile’s memory, stopped in time. Nick saw his father suddenly, walking down streets he thought he knew, amazed at buildings that shouldn’t be there.

“They seem to like it,” Nick said, nodding to the crowd.

“What’s not to like? Well, it’s that time.” He tossed back his drink.

He seemed to be waiting for them, but when Nick said, “We’ll just finish these,” he nodded and said, “Enjoy. I’d better get back upstairs. I don’t want to miss anything.”

“You’re in a box?” Nick said involuntarily. With the Party men. A bird’s-eye view, to look over the crowd.

Bielak smiled weakly. “No, higher. The cheap seats.” He moved toward the stairs.

“C’mon,” Molly said, “they’re starting.”

“No. I don’t want him to see us.” A legman. “Wait a minute.”

The crowd had started yelling and clapping, and Nick heard the opening drums of “Sing, Sing, Sing.”