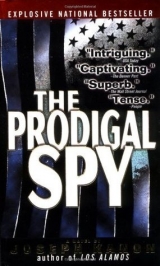

Текст книги "The Prodigal Spy"

Автор книги: Joseph Kanon

Жанры:

Шпионские детективы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

No note. The papers were bills, scattered now from what must have been a neat pile, making sure everything was paid before he got on the train. Nick opened a drawer. Was there really a list? There seemed to have been no effort to find it, no search. The inside of the desk was untouched, folders of letters and bills and what seemed to be official documents with his name, the paper trail of socialist life.

Nick heard a noise in the hall, the whirring of the elevator. One of the neighbors would see the body now, glance across the lawn as he went out, curious, then cry out and run back for the telephone. Should he do it first? But the idea of calling the police in Czech defeated him. Let someone else do it. Maybe instead he should slip down the stairs, go back to the hotel and his own life. Call Anna later. What more could he do here? All this paper, receipts and letters, some in Russian, the desk of a foreigner. Only on the grass, strangely young again, had he been his father.

In the top drawer he brushed aside pens and paper clips. A passport, Russian, his father’s. He drew out a manila envelope dark with age. Newspaper clippings, in English. His disappearance, his press conference, a loose scrapbook of disinformation. Why had he saved them? Then Nick saw that each of the clippings had family photographs–the three of them in front of the house on 2nd Street; the old wedding picture, blurred on newsprint; his parents shaking Truman’s hand at a reception. Their tabloid life. At the bottom of the pile were two real photographs, worn at the edges. His mother, young, maybe during the war, shoulder pads and short skirt, a vivid lipstick smile, her mouth open with the beginning of a laugh. The other was a boy in hockey gear at Lasker Rink, a wintry Central Park in the background, the boy unaware that he was being photographed by a spy. Nick looked at himself. He wished now that he had been smiling, that every time his father had looked at it he’d seen what he wanted to see, his happy boy, not somebody caught from behind a tree. Too late. His eyes filled, and he wanted to make a noise again. The photographs were like the stillness of death. If you gave in to them, you drifted away to another place. Nothing ever came back.

He was still looking at the pictures when he heard the sound in the next room. He raised his head. Two policemen faced him, guns drawn, the small machine guns they held with two hands, more menacing than revolvers. One of them shouted in Czech, looking at the blood on his pants.

“I’m sorry. I didn’t hear—”

Another shout. He pointed Nick toward the wall with the gun and said something in Czech, brisk. Now the gun was being jerked up, a signal to raise his hands. When he did, staring at the gun, the other frisked him, patting up and down his sides.

“I was going to call—”

Then a storm of Czech, perhaps to each other, their voices rising in frustration when he didn’t answer.

“I don’t understand.” But then he did. When they snapped on the handcuffs and pushed him out of the room, the gun poking at his back, he understood, dazed, that he was being arrested.

Chapter 12

THERE WERE PEOPLE on the lawn now, huddled over the body, some in uniform, one old lady standing behind, clutching at her winter coat–the neighbor, finally?–but they wouldn’t let him stop, pushing him with the guns down the path. He bumped his head against the car when they shoved him in, the sharp crack of pain the only thing real in what seemed to be a cartoon. His wrists, clamped behind him, were caught in the metal cuffs. One of the policemen in the front seat swiveled around, pointing the gun at him, and he watched the barrel bounce against the seat as the car took off down the rough road. A pothole could set it off. He closed his eyes. No siren, just the racing car, rumbling now over cobbles, taking a corner too fast, the speed itself official. He was pitched forward when they stopped, almost into the gun, then doors slammed and a hand pulled roughly at his arm.

The building was a blur, bulletin boards and clicking typewriters, heads looking up. They’d take him to a desk now, to someone who spoke English, so he could explain.

Instead he was thrown into a chair and photographed, the flash blinding him, then yanked down the hall to a bare room. Not a cell. A plain table, two chairs, a picture of Husak on the wall. They pushed him down into one of the chairs, hands still behind his back, delivered another volley of incomprehensible Czech, then left. The door slammed.

No one came. What should he do–kick the door, demand to see someone, to have his one telephone call? But there were no rights here. He was a foreigner with blood on his clothes. Maybe they were watching him. He looked around. No mirror, just blank walls, Husak looking down. The bump on his head throbbed. They couldn’t leave him here, throw away the key–a child’s fear. An interior room, one small window facing a wall, the light always the same, no way to tell the time until it was dark. The story was the important thing now, what to say. The truth would start another web, catching him, sticking to him like his pants. He looked down. Would it never dry? He felt his eyes fill again. You always brought me luck. But he hadn’t. Dancing, careless, while his father made a new plan, an emergency exit that hadn’t opened. Why the change? He sat back, still dazed, and waited to see what would happen.

It was at least an hour before they came, or had waiting distorted his sense of time? His hands were numb. The two policemen again, with another, not in uniform, his fat neck spilling over his collar. He gave an order, the cuffs were taken off, and while Nick rubbed his wrists, the new man leaned over the table, glaring and talking into his face. When Nick didn’t answer, signaling that he didn’t understand, he said, “Ach,” a sound of disgust, and sent one of the policemen out. Now they all waited, the big man in the suit pacing. Eventually there was a knock on the door and another man in a suit came in. This one was slight, with a moustache, and his eyes took Nick in like a jeweler. Then he listened to the big man grumble in Czech. He turned to Nick.

“This is Chief Novotný,” he said, pointing to the big man. “Criminal Investigation Department.”

“Am I under arrest?”

“He’d like to ask you a few questions,” he said formally, sidestepping it. “I will translate. My name is Zimmerman.” He caught Nick’s glance. “Sudeten,” he explained, “but Czech.” An unexpected courtesy, almost social.

Novotny snapped at him, evidently telling him to get on with it. He nodded. Good cop, bad cop. Novotný handed him Nick’s passport. What had happened to Molly’s?

“You are Nicholas Warren.”

“Yes.”

“And how do you come to be in Holečkova this morning? In Pan Kotlar’s flat. You were acquainted?”

“We met at a concert last night.”

“Concert?”

“Yes, Benny Goodman.” The sound of it absurd, even to him. Novotný grunted. “He invited me to come for coffee.”

“A kaffeeklatsch,” Zimmerman said. “Why?”

“He used to be an American,” Nick said. Used to be. “I think he wanted—”

“News from home,” Zimmerman finished.

“Something like that.”

“So early. In the morning. Not the afternoon coffee.”

“I’m leaving Prague today. It was the only time. So I went. But he was–I found him on the grass. He was dead. He’d been dead for a while.”

Zimmerman looked at him sharply. “How do you know?”

“His skin was cold.”

“I see. You examined him?”

“To see if he was alive. That’s why the blood.”

Novotný interrupted in Czech; the other answered him, annoyed but polite. Then he turned back to Nick.

“But you went into his flat?”

“To call the police.”

“But you didn’t.”

Nick pointed to the policeman. “He got there before I had the chance. Someone else must have called.”

“Yes. You were there long?”

“A few minutes. Look, what’s this all about? He was dead. Do you think I killed him?”

“I don’t know, Mr Warren. I don’t know that anyone killed him,” he said carefully. “Do you have reason to believe someone did?”

“I didn’t mean that.”

“No. Last night, at the concert, how did he seem to you? Was he upset in any way?”

Desperate, Nick wanted to say. But had he been, or did it just seem that way now? “I don’t know. I don’t know what he was usually like. He seemed all right to me.”

“So you were surprised, this morning.”

“Of course. It was–horrible.”

There was another exchange of Czech, then Novotný went to the door, said something, and came back with Nick’s canvas bag. By the body. Why had he forgotten? Novotný handed Zimmerman Molly’s passport and the tickets.

“You were going on from coffee? To the station?”

Caught. “Yes, later.”

He opened Nick’s passport. “Your visa includes an entry permit for a car. You are aware that it is illegal for you to sell a car to a Czech citizen?”

“I didn’t sell it.”

“A present, then, perhaps? You were not by any chance leaving it for Pan Kotlar?”

A hopeless tangle now. “No, why would I do that?”

“If you had just met. Yes, I agree. But you were traveling by train?”

Think. “It was acting up. I was going to have it fixed and come back for it.”

“You’re very trusting, Mr Warren. To leave a car.”

“The hotel would take care of it.”

“But you couldn’t wait.”

“No, I had to be in Vienna.”

“What is your business, Mr Warren? You’re a journalist?”

“No. I’m at the London School of Economics.”

“A student?”

“A research assistant.”

“With business in Vienna.”

“I’m traveling with someone. She had to be there.”

He fingered Molly’s passport. “Miss Chisholm,” he said, pronouncing it correctly. “Your friend?”

“Yes.”

“She was not invited for coffee?”

“She had other things to do.”

“It’s a pity you did not join her, Mr Warren.”

He turned to Novotný and reported in Czech, a brief summary.

“You had better think of a better explanation for the car, Mr Warren,” he said, almost confiding. “He’s interested in the car. By the way, the next Vienna train doesn’t leave until late afternoon. I thought you should be aware of that.” Nick stared at him. “Now, quickly please, what did you see in the flat? Had anyone been there?”

“I think so. Furniture was pushed around, as if there had been some kind of fight. Chair moved out of the way. I suppose he might have done it himself, but why?”

“Anything else?”

“Scrape marks on the railing. But there was nothing on him to make a scrape with, so I assume it was someone else.”

Zimmerman nodded approvingly. “If it was made then. How long did you say he’d been dead?”

“I don’t know. I can’t tell. He wasn’t stiff, just cold.”

“All right. Thank you.” He stood up, talking again to Novotny. “Think about the car.”

“Can I go now?”

“Go? Mr Warren, I’m afraid you are in difficulties. Unless of course Pan Kotlar seemed–agitated to you last night. It might have been. Otherwise, the police will be interested in you.”

“I don’t understand. Aren’t you the police?”

He smiled. “Actually, I was chief of police. Until last year. A year can make a great difference here, you see. Today, Chief Novotný. He’s more comfortable with the regime, or perhaps they with him–it depends how you look at it. Now I help him.” Another tram driver. “A research assistant,” he said, his voice ironic. “But I’m glad of the work. It’s hard, you know, to break the habit.”

They brought Molly in sometime after noon.

“Nick. Thank God,” she said, her face drawn and nervous. “What’s going on? I’ve been frantic.” She moved toward him, then looked at the police and stopped. Novotny watched them blankly, shut out by language, but Zimmerman followed her with interest.

“I don’t know. There’s some kind of mistake. The man we met last night, at the concert–I found him this morning, dead. They didn’t tell you?”

“Dead?” she said, stunned, not taking in the rest of it. Her face softened. “Oh, Nick.”

“Mr Warren was with you this morning?” Zimmerman said.

Molly nodded.

“What time did he leave?”

Molly looked to Nick for help. “I don’t know. I was asleep.”

“The maid said very early,” Zimmerman said. “You don’t know exactly when?”

“I didn’t want to wake her,” Nick interrupted. Then, to Molly, “I went to get the tickets. For the train this afternoon. You know. I didn’t want to wait till the last minute.”

“Evidently,” Zimmerman said dryly, still watching Molly, who simply stared, following a game. “And yet you waited there,” he said to Nick. So they’d already checked.

“I had a coffee. It was too early to go to his place.”

“So much coffee,” Zimmerman said. “You have business in Vienna?” he said to Molly. But she seemed not to have heard him.

“Dead?” she said to Nick. “He was dead? How?”

“That is what we’re trying to determine, Miss Chisholm. A fall from the balcony. An accident, perhaps,” Zimmerman said blandly. “But Mr Warren’s presence there naturally raises some questions for us. You understand. You have business in Vienna?” he said again.

Molly looked at him, unsure, then gave a nod, faint enough to be retrieved. He took up her passport, thumbing through it.

“You’ve been to Prague before. May I ask what brings you back?”

“I wanted to show Nick.”

“Not on business then, this time? You did not apply for a journalist’s visa, I see.”

“No. It was a personal trip.”

“To see Prague,” Zimmerman said. “Again.” He put down the passports. “So you cannot tell me when Mr Warren left this morning.”

“Sometime after six. He was still in bed then. I saw the clock.” Had she?

“He left around six?”

“Later. I don’t know when exactly. I fell back to sleep. Why?”

“It’s useful to know these things. Chief Novotny will want it for his report.” Novotny looked up at his name. “Or perhaps not. Perhaps he has his own idea. Don’t be alarmed, Miss Chisholm. If you were under suspicion, we would have questioned you separately, before you could talk to Mr Warren here. That’s the usual procedure. Of course, Chief Novotný may not know that. He is new.” Zimmerman sighed. “But it’s useful, these details. For instance, you have not yet packed for your trip?” The disheveled room, noticed.

“Molly leaves everything to the last minute,” Nick said.

Zimmerman looked at him. “Now she will have more time.”

“But she has to leave today,” Nick said evenly, facing her.

“I think Chief Novotný would prefer her to stay,” Zimmerman said easily, “until we finish. Don’t worry, the tickets will still be good. Unless, of course, your car is fixed in time.”

Molly raised her eyebrows, finally thrown, but before Nick could say anything there was a knock and another policeman handed Novotný a folder. He pulled out a report sheet and grunted as he read, only handing it to Zimmerman when he had finished. Zimmerman went through it quickly, nodding and speaking to Novotný as he read. A small explosion of Czech back, then more talk, not quite an argument, Novotný bristling, clearly irritated by an inconvenience. Nick watched them, then looked over at Molly and saw that she was frightened. When he placed his hand on hers, it was cool to the touch.

“There was no blood in the flat,” Zimmerman said, not a question. “Tell me again about the blood.” He nodded to Nick’s pants.

“When I was checking. To see if he was alive.”

“Is that why you went back to the flat? To wash it off?”

Nick looked at him. “I didn’t go back. I’d never been there. I found him and then I went in to call you.”

“But not right away. First you went through his desk.” He glanced down again at the report. “Pani Havlíček–that’s the neighbor–said she saw you holding his head.” Molly took her hand away as if the blood were there, drawing her in. But her eyes were soft, upset now, the death real, not a story. “Is that usually the way you check a pulse?”

Someone watching, even then. “I don’t know. I didn’t know what I was doing. You know, I didn’t expect—”

“What, Mr Warren?”

“To see a body there.”

“Pani Havlíček didn’t expect to see you there either. She said you stayed for some time. Holding him.” He glanced over at Novotný, who, bored, was now stretching his tight collar and looking out the window. “Of course, it might have seemed long to her. It’s often the case. She also said she heard noises in the apartment. Just before dawn. Another light sleeper.” He glanced at Molly. “A little commotion. Of course, it may have seemed louder to her than it was. It’s possible, at that hour.” He was walking around the table, talking to himself. “A noise when you don’t expect it. Pan Kotlar himself, perhaps. There was alcohol in his blood. If he was unsteady– It’s difficult to be precise about these things.”

Nick looked up at him. “What time is dawn?”

Zimmerman paused, a sliding look toward Novorny. “Before six,” he said to Nick. “There were pills,” he continued, walking again. “For illness. No marks on the balcony. Of course, these may have been missed, if no one was looking for them.”

“They were there.”

“So you said. What caused them, do you think?”

“I don’t know. A belt buckle, buttons–something metal.”

“And what could that mean?” Zimmerman said, almost playing.

“That someone scraped against it when he pushed him over,” Nick said flatly.

For a minute no one said anything. Zimmerman looked down at the folder as if he were thinking it over, not just playing for effect. It was when Nick saw him glance at the window that he realized Zimmerman was just waiting to see if Novotný had understood.

“I see,” he said finally. “That is your idea?”

“Yes.”

“Oh, God,” Molly said quietly.

“I don’t know if Chief Novotný would agree with you. As I said, he has his own idea. And you know, sometimes the obvious solution is the right one. I’ve seen this many times.”

“He didn’t kill himself.”

“You’re sure? If I may say so, Mr Warren, the obvious solution would be more convenient for you.” Directly to Nick, almost an instruction. “An older man, sick, it’s a common thing. Even the method. It’s a disease with us Czechs, you know. I’m not sure why. All through our history. Defenestration. So many have chosen it.”

A courtyard in the Czernin Palace. What had Masaryk said?

“The housemaid’s way out,” Nick said.

Zimmerman’s eyes widened in appreciation. “I see you know our history.”

“He wouldn’t have taken it either.”

“You know that, after so little acquaintance?”

Nick lowered his head, quiet.

“No, Mr Warren, it would all be very simple. A sick man, a little drink. Our chief would sign the papers. Everybody goes home. Except, of course, for you. A foreigner. At the death scene. Now it’s not so simple.” He took one of the chairs and sat down, facing Nick. “What are you doing here, Mr Warren? Why did you come to Prague?”

Nick looked away. “To see it.”

“A tourist. Who drives in and takes the train out. Who meets a stranger, and the next morning he’s dead. Mr Warren, this is a charade. I’m not like our good chief. I like to know the truth. It’s a habit. So.”

Why not? Hadn’t he been telling Nick all along that he knew it was someone else? The wrong time. The blood. Then why press at all? Simple curiosity? Or a final trick question before he’d have to let him go? There was no one to trust here. Nick said nothing.

Zimmerman looked down, opened the folder, and shuffled through papers. Newsclippings, yellow. Of course they’d gone through the apartment. Now he was fingering the hockey picture.

“A remarkable resemblance,” Zimmerman said quietly, still shuffling, indifferent for Novotný‘s benefit. He didn’t want him to know. “A relative?”

Nick said nothing.

“It’s unusual, Mr Warren, to hold the head of a dead man you didn’t know.” He paused. Tell me, please.“

“Why? You already know.”

“I would rather you told me. It’s better. For the report.” He continued looking down, as if they were talking about something else.

“He was my father,” Nick said.

“And yet you have different names.” Zimmerman looked up. “A detail.”

“My mother remarried. I took my stepfather’s name.”

“I see. Thank you. And now will you tell me why you didn’t say this before? What are you doing here, Mr Warren?”

“I came to see him. I didn’t want anyone to know.”

“Why?”

“It would hurt them, if they knew. My family.”

“No, why did you come?”

“I wanted to see him.”

“After so many years?”

“Before it was too late.”

“You knew he was dying?”

“No. Old.”

Zimmerman closed the folder. “You got here just in time. I’m sorry. This must be difficult for you. May I offer you a piece of advice? Do not create more difficulties.”

“He didn’t kill himself.”

“How can we know that, Mr Warren? From a few scrape marks?”

“Somebody killed him.”

“Why?”

Nick looked down. “I don’t know.”

“Then let us confine ourselves to what we do know. For the moment. I understand that Pan Kotlar was much affected by the death of his friend Miloš Brokov. There was a discussion about suicide. You were there, I believe.”

“That’s not—” Nick stopped. “How do you know that?”

A flicker of embarrassment. “Pan Kotlar’s wife returned this morning from visiting relatives.” He looked up. “She was, by the way–visiting relatives.” Had his father suggested it, knowing? Or had he just wanted to make it easier to get on the train? Had he said goodbye? “Chief Novotný was busy, so I took the opportunity to interview her. Separately. Our usual procedure.”

“She told you about me.”

Zimmerman nodded and touched the folder. “I confess I am not so clever, even with the resemblance.” He paused. “Was there any reason for her not to mention this?”

“No.” She hadn’t known any of it.

“So you remember this discussion? She said Pan Kotlar was depressed. Is that so?” Building another case, away from the truth.

“No, he was drunk.”

Zimmerman started, surprised by the bluntness.

“An emotional time,” he said calmly. “A friend’s death. And of course seeing you. Your presence—”

“Is that what she said?”

“She said he was not himself.” The denunciations, already begun. The way his father said it would be, the standard procedure. “Was that your impression also?”

“I don’t know what he’s usually like.”

“But he was upset by his friend’s news?”

“Yes.” A pinprick of disloyalty; so easy. “Anybody would be.”

“Your visit, it was a pleasant one?”

“Yes.”

“No quarrels? Sometimes, I know, these things don’t always go smoothly. So many years. And of course the events of his life.”

“That was a long time ago.”

“Yes, but often there are feelings–you think it’s over and then they come up.”

“He was happy to see me.”

“And you, were you happy to see him?”

Had he been? “Yes, very.”

“Yet you were leaving today. A short visit.”

“This time.”

“A kind of trial run?” Zimmerman said, pleased with himself for knowing the idiom.

“Yes.”

“Your father knew you were planning to return?”

“Yes.”

“But would you say he was distraught? At your leaving? With his health—”

“No, I would not say that. You would. What are you trying to prove?”

“I’m trying to understand, Mr Warren. How it was.”

“No. You just want me to say he killed himself. I don’t want any part of this. You don’t need me–you already know. Can we go now?”

Zimmerman looked at him carefully. “I’m afraid you don’t understand the situation. Miss Chisholm may go if she likes,” he said, turning toward her. “Though I must ask you to cancel your business in Vienna. It would not be advisable for you to leave Prague just now. You, Mr Warren, are another matter. It is not, of course, my decision–I’m only assisting Chief Novotný. But I suspect he would wish you to stay here.”

“Am I under arrest? What for?”

“No, you are being detained for questioning.”

“Whatever that means.”

“It means you are being detained for questioning. You see, Mr Warren, you are a spanner.”

“What?”

“A spanner in the works. It’s not correct?”

“A monkey wrench,” Nick said.

“Ah, it’s a Britishism, spanner?” Zimmerman nodded. “A wrench. It gets stuck in the machinery. A cause of industrial accidents. This is what has happened to Chief Novotný. Everything runs smoothly and then you fall in. Now he must decide what to do with you to fix it. How does he explain you? Just the fact of you raises questions. What if his idea is wrong?”

“It is.”

“Then he must find another. I have been trying to suggest to you–I hope you understand–that you should not make this difficult for him. He might–this can happen–he might find the wrong idea. He might find it in you.”

Nick stared at him. “You don’t think I did it.”

“It doesn’t matter what I think. I’m only an assistant now. You want him to believe this was a crime? Then it becomes a problem for him. Given the victim, perhaps a political problem. That would be serious. Me, I don’t interest myself in politics. But I am interested in you. I’m a policeman. A man is dead and I want to know why, I can’t help it.” He paused. “I would like you to help me. But Chief Novotný has other concerns. Not why. What to do. You must understand that difference. For him, the wrong solution, any solution, might become the right one. Unless, of course, I can explain you.”

“He can’t prove anything.”

“Proof can be a small thing, Mr Warren, if you want to believe it. A telephone call that isn’t made. A presence in someone’s flat, stained with blood.” He touched the folder again. “Perhaps a resentment that explodes–just like that, a kind of accident.” He looked up. “A car that isn’t broken. Many things. Which are important? Which do you believe? It’s difficult to know, until they fit. Help me, Mr Warren.”

And not Novotný. Unless they were really one person, not separate at all, like the mimes’ shadows at Laterna Magika.

“Nick, let me call your father,” Molly said, anxious.

“No,” he said quickly. The last thing he wanted, the wounded surprise on Larry’s face, then the mess that would follow, with everyone in on the act. “We can work it out here.”

“How? This is ridiculous.” He turned to Zimmerman. “Do I get a lawyer?”

“If you are officially charged. Let’s hope that won’t be necessary. We can inform your embassy, if you like, that you have been detained. Though I should warn you that that might take some time. I don’t want you to think it’s a lack of interest on their part, but there are procedures to follow.” He lowered his voice. “And of course it makes difficulties for the chief. Questions asked. Paperwork. I speak from experience. I can recommend that you be allowed to return to your hotel tonight, if we need to continue tomorrow.”

“But you can’t guarantee it.”

“No. Not if you are charged.”

“Nick—” Molly said.

“It’s all right. You go back to the hotel and wait.” He turned to Zimmerman. “Can I call her later?”

“As you wish.”

“I’ll stay with you,” Molly said.

“No.” He looked at Zimmerman. “May I talk with her privately?”

Zimmerman shook his head. “It’s not allowed.”

“Can I go to the bathroom, then?”

Zimmerman held his eyes for a second, then nodded, a faint smile. “With an escort.”

After an exchange with Novotný in Czech, one of the policemen led them out. In the hallway Nick hugged her goodbye.

“Nick, stop arguing with him.” Her voice was low, worried. “It doesn’t do any good.”

He stood still. Larry’s advice to his father, years ago, in the study. You’re not doing yourself any favors in there. Were they so alike?

“Somebody killed him, Molly.”

“But he thinks you did. You’ve got to call your father.”

“No.”

“Nick, you’ve got to get out of here. You’re only going to get in deeper. How are you going to explain—”

“Ssh. I’ll think of something. Look, go to the embassy. They won’t keep me here if someone makes a stink. Novotný doesn’t want to charge me with anything–it would be a real pain. It’s Zimmerman who can’t get enough. By the way, I told him there was something wrong with the car–that’s why we were taking the train. You heard the noise in the motor when we came back from the country, okay?”

“I don’t understand any of this. I hate it. What train? What happened?”

“Later.” The guard came over to nudge them apart. “Just go to the embassy.”

“The embassy?” Nervous, her face dismayed.

“Yes, tell them to get me out of here. They can’t keep me without a formal charge.”

“And what if they do charge you?”

“Then they were going to do it anyway.”

“What if he’s right? That it takes them forever to—”

“Molly,” he said, stopping her. But what if it did? An in-box of tourist problems? He’d have to flash their attention. A flare, someone they’d know. “Tell them I’m working for Jack Kemper. In the London embassy. They’ll move. I guarantee it.”

“Who?”

“Just do it. Please. I’ll explain it all later.” He kissed her. “Do it.”

“Nick, what are you doing?”

“Kemper,” he said. “Don’t forget. His wife’s name is Doris.”

“Doris?” she said, flailing, but before he could say anything else, the guard led him away.

“Later,” he said over his shoulder, watching her fold her arms across her chest as if she were cold.

The guard stood at the door while he washed his hands. Flakes of dried blood, forgotten, came off in the water, turning it rust-colored. He stared at the drain, suddenly weak, then washed again, and again, until the water ran clear. On the way back, passing a long row of cubicles, he spotted Anna over a waist-high partition. She was bent over a desk, her arm moving, and for a moment he thought she was washing her hands too. Then he saw that she was writing, signing a paper. He imagined the statement–his father’s depression, the upheaval of the weekend, his state of mind, all signed away now, more blood down the drain. When she looked up, her face blotchy from crying, she was startled to see him, as if Nick had died too. Then she took in the guard leading him by the arm and looked away, refusing to meet his eyes.

“Anna,” he said, forcing her to turn back. “I’m sorry.”

“They said you found him,” she said, her voice distant with grief.

“Yes.”

“He wanted me to go to my sister’s. After the concert. I thought he wanted to be with you. Was that it?” The troubling detail.

“No.”

She nodded, piecing it together, then turned away again, cutting him out.

“I wish you had never come,” she said.

Zimmerman was waiting with a pot of coffee, talking to Novotný, who sat on the windowsill eating a salami sandwich.

“Tell me about your trip to the country,” Zimmerman began.

“It rained,” Nick said dully.

“Yet you told the hotel you were going to Karlovy Vary. Why?”

Deeper. Zimmerman’s voice droned on, elaborately polite, refusing to be discouraged by Nick’s vague replies. There was always another question. He had all the time in the world, his patience as relentless as a light in the face. Wasn’t that the way they were supposed to do it? The bright lamp hurting your eyes. No sleep. Shouts. Beatings. But nothing here was what he’d expected. He thought of the watchtowers at the border, his first sensation of fear, a movie iron curtain bristling with menace. But the countryside had been placid, the pokey guard interested only in his car. Now Zimmerman talked patiently, lulling him. But what did he really want? There was no way of knowing. The polite questions might be as deceptive as the placid landscape, still after all lined with barbed wire. So Nick stalled, repeating himself, giving away nothing that mattered. And after a while it was easier. The story became real to him. There was something wrong with the car. Molly did have business in Vienna. Why not? He saw that Zimmerman recognized it too, the tipping point after which nothing would be revealed, because the lies were now true. His eyes, shrewd, witnesses to a hundred interrogations, began to anticipate Nick’s answers –the cards fell where he expected them. Why go on? Unless this was part of the weakening process.