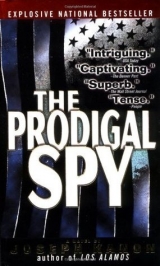

Текст книги "The Prodigal Spy"

Автор книги: Joseph Kanon

Жанры:

Шпионские детективы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

“What’s the matter?”

“Don’t you think it’s funny, his running into us like that?”

“Maybe. Anyway, he has seen us, so what’s the difference? Come on.”

But he held back. Were their seats visible from the balcony? “Not yet. Give it a minute.”

“Okay. So what’s our cover?” she said mischievously. “Want to dance? Can you?”

“Can you?”

“In this crowd?” She laughed, and Nick took in the couples around them, exuberant but awkward, as if they had picked up the steps from old movies.

“Chicken,” she said, leaning into him. On the stage, the brass section stood up, horns blaring, infectious.

“Say that again.”

“Chicken,” she said, putting her hand in his to start the movement. And then suddenly he didn’t care who was there and he swung her out and they were dancing, his arm reaching over to turn her around, then lead her back, laughing at the surprise in her face. How many years had it been? You’ll never know when it will come in handy, his mother had said. Mrs Pritchard’s class, an agony on Tuesday nights. The girls tall, in flats to mitigate their growth spurts, the boys resentful, shirts never quite tucked in. When am I ever going to have to know the rumba? On boats, darling, she’d said. They dance on boats. And the lindy, another generation’s dance, learned step by step but now, like riding a bicycle, all familiar and fluid, so that he could do it fast, Molly trying to follow, arm over, then back, finally come in handy, here of all places.

He felt the heat in his face when the drum solo began, but Molly was smiling at him, excited, and they kept up with each other now, the pleasure of the movement like a kind of foreplay that made everything else disappear. He noticed vaguely that people had made space around them, watching and stamping their feet, but he kept his eyes fixed on her. The song started its false diminuendo, everything running down and building at the same time, and they danced close, keeping pace, waiting for the break. Sweating. “Wow,” she said, laughing, panting a little. “No, you,” he said, meaning it, because he didn’t dance, not like this. Then it came, the sudden loud blast of the finale, irresistible, and they were dancing wildly, grasping hands to hold on, their circle of movement spinning wider to fit the music, until the dramatic up-tempo crash, the real climax, and they hung on to each other, winded, while the entire hall shook with applause. Goodman’s crowd-pleaser, the same frenzy.

The applause was for the band, not for them, but he heard it like an alarm clock, bringing him back. They were supposed to be inconspicuous, not drawing a crowd. He dragged Molly outside the circle of people and stood for a minute against the wall, catching his breath.

“Who would have thought?” she said, smiling, hanging on to him. She reached up and wiped his temple, smoothing back the damp hair.

“We’d better get back,” he said, but when he looked up he saw that his father had come to find them and was standing there watching. He felt embarrassed, as if they’d been caught necking. Molly followed his gaze and turned.

“Did you see?” she said to his father, still smiling.

“A killer-diller,” his father said wryly. “We were wondering what had happened to you.”

“My fault,” Molly said lightly. “I couldn’t resist.”

His father looked around. “How about a cigarette?” he said. Then, to Molly, “Tell Anna we’ll be right there.”

Molly looked surprised at her dismissal, but he took Nick’s arm before either of them could say anything and led him out the door. Nick felt the night air on his sweat and shivered.

“Outside?”

“Yes,” his father said, still leading him.

“Sorry. We shouldn’t have done that.”

His father waved it aside, a matter of no importance. “Here,” he said, lighting him a cigarette. “Listen to me, Nick. Carefully, please. We don’t have much time.”

Nick leaned against the building, still sweating, and took a gulp of air. Now what?

“We have to make a change.”

“What’s wrong?” he said, alert now.

His father shook his head. “Just listen. I need you to do something for me. Tomorrow morning go to the train station and buy a ticket for Vienna–you’ll need your passport. The Berlin train at eight-ten. You shouldn’t have any trouble. An American. Even at the last minute.”

“What are you talking about?”

He put his hand up. “Just listen. If it comes up, which it shouldn’t, you had a quarrel with Molly–these things happen. Take a bag with you, what you’d take if you were leaving. After you buy the ticket, go to the men’s room, the one near the platform. First stall on the right as you enter. You leave the ticket there–an accident, but you don’t realize it. You don’t miss it until the train is about to leave, so you retrace your steps, but you can’t find it. Too late. You don’t report it. But missing the train–maybe it’s a sign you should make up. So you go back to the hotel. You do make up–no need to take the train after all. But leave that afternoon. Drive to Vienna. Don’t stay in Prague any longer.” He paused, as if he’d forgotten a detail in the rush. “Don’t talk to anybody at the station. That’s important. You don’t see me, not even if we’re alone there. Do you understand?”

Nick stared at him, trying to catch up. Was he crazy? “You can’t do this.”

“Do you understand?” he repeated.

“You can’t just get on a train.”

“Yes. It’s the ticket that’s difficult. A Czech would get it early, with the visa. No one goes to Vienna at the last minute. But for you it’s easy.”

“No one goes to Vienna at all.”

“Russian Jews,” his father said. “They have exit visas. This is the train that connects to Vienna. It’s how they leave. Don’t worry, I have papers.”

“Yours?”

“Someone’s. They won’t bother me. Once I have the ticket I’m all right.”

“No risk at all.”

His father looked up at him but didn’t answer. “When you get to Vienna, stay at the Imperial. I’ll contact you. And don’t tell anyone you’re there–anyone.”

Nick dropped his cigarette and took him by the arms. “What’s going on? You can’t do this,” he said again. “What if it doesn’t work?”

“It has to. It’s not what I planned, Nick. But now we do it this way.”

“But why? This morning—”

When his father didn’t answer, it occurred to Nick, a chill like the night air, that it had always been the plan —not the elaborate exchange but an escape, clandestine like the rest of his life, drawing Nick in deeper, one story into another, until he was on a train platform buying a ticket, an accomplice. No risk at all, unless he was caught.

“What about your list?” he said. “Your documents?” Had he made that up too?

“There isn’t time now. But they’re also here,” he said, tapping his head. “It should be enough.”

If they exist at all, Nick thought. Now there were other papers, good enough to use on a train, insurance policies. How long had he had them?

But when he looked into his father’s face, he saw that the smooth confidence of the morning was gone. Now there was the worry he’d noticed earlier, something hasty and makeshift. A new plan, while Nick had gone dancing.

“What’s happened? Are you in some kind of danger?”

His father shook his head. “Not yet. I just have to do it differently.”

“Not like this. Let me go to Paris and—”

“No,” he said abruptly. “Go to Vienna. It’s important, Nick, please. Do this one thing for me. There’s no danger to you. A lost ticket–you can’t be blamed for that.”

“I wasn’t thinking about me.”

“No,” his father said, his eyes softening, as if he’d received an unexpected compliment. “So you understand?”

“How long do I wait in Vienna? If you don’t show up?”

“In that case you won’t have to wait at all,” he said, almost wry again. “But let’s hope for the best. It’s simple, Nick. Just keep your head. We’ll be all right.” He paused and looked around. “Well. We can’t stay here. You don’t want to be seen with me. Tell Anna to come out. Say I’m not feeling well.”

Nick raised his head to speak, but his father’s eyes were steady, pragmatic. There was nothing more to be said. Nick looked away. “I’ll get them.”

“Just Anna. You stay here.” A little smile. “Have another dance.”

When Nick moved from the wall, his father stopped him. “Nick?” he said, his voice anxious, then reached for him, a bear hug, no longer caring if anyone could see. The platform goodbye they weren’t supposed to have. He held Nick for a minute–the same clutch, unmistakable -then pulled away.

“What was that for?” Nick said, to cover his embarrassment.

“For luck. You always brought me luck, remember?” Sitting at his side while his father played poker with the other men, watching the cards, happy to be up late.

“Not always,” he said.

“Yes, you did.”

Inside, the band was still playing, the hall light and warm, as if nothing had happened. “Memories of You”, a romantic low-register solo, calming the crowd down after the raucous opening number. Anna left even before he’d finished his message, snatching her coat, an attentive nurse. Molly raised her eyes.

“Tired,” Nick whispered. “We’re on our own.”

She smiled, obviously pleased, and put her hand on his. He drifted with the music, relieved that they couldn’t talk. What could have happened? Something at the funeral? This morning there had been a plan. This was more like flight, the bag ready at the door. What had spooked him? “Goody, Goody”, a speakeasy song, fleshed out for the big band.

“You okay?” Molly said, looking at him.

He nodded, forcing himself to smile. Why was happiness so hard to fake? Everybody else was beaming, a kind of collective euphoria. This was the way his father had sat, not even hearing the music. He grinned. In case they could be seen from the balcony.

The band was brought back twice, and even when the curtain was down people kept clapping, reluctant to leave the party. They followed the crowd back to Wenceslas, where it spilled down the long street, clumping at tram stops and the few bars still open for a late drink. Molly wanted to go on to Laterna Magika–‘We can still catch the end’–and because they wouldn’t have to talk there either he went along, his arm around her shoulder, not giving anything away.

It was in a café at the bottom of the square, off Národní Street, and the minute he walked in he knew it was a mistake. The dark room, smoky, filled with shadows, was the part of him he’d been trying to push away. They couldn’t take a table without interrupting the show, so they stood at the bar in the dark, and Nick found himself scanning the room, looking at faces to see if any of them were looking back.

The mimes worked in front of a bright spot, forming shadows against a screen, like children making rabbit ears on the wall with their fingers held up to a lamp. The play between the actors and their own larger shadows caused a trick of the eye, a clever chiaroscuro, but all Nick saw were the shadows, dancing, then elusive, sliding toward the edge until you could no longer see where they ended and the real dark began. The customers, sitting at cabaret tables, gave off the same effect, sometimes visible in the light, then vanishing into the recesses. No wonder the Czechs liked Goodman, the bright lights and the simple, bouncy music. This was the native product, all shadows, a city practised at fading into doorways.

He went into the men’s room, grateful for the light. A man, cigarette dangling, stood at the urinal, so he went into the stall. What if there was someone in the stall tomorrow? What did he do, keep going back until it was empty? He pulled the chain, looking up at the flush box mounted on the wall. He’d imagined a toilet with a back, a convenient shelf. Where did you leave the ticket, on the paper dispenser? Why had his father changed his mind? The man at the urinal said something in Czech over the plywood wall, hearty, maybe a joke about the effects of beer on the bladder, but it could have been anything. What if someone spoke to him? Nick just nodded to him blandly when he came out, not even stopping to wash his hands, afraid of being caught out by language. He pushed open the door to a round of applause.

“Aren’t they wonderful?” Molly said brightly. “There’s one more set. Want to sit?”

“No. Do you really want to stay?”

“You don’t like mimes. Here, finish this.” She handed him a brandy. “Ten minutes, okay?”

He took a long pull on the drink to burn away his mood. When he looked up over the glass, a shadow had come out of the wall.

“We meet again,” Marty Bielak said. “You seem to be everywhere tonight.”

“That makes two of us.”

“Well, a nightcap.” He held up his glass. Where else had he been? The Alcron. The Café Slavia. The legman making his rounds. Items for tomorrow’s column. Just like the old days. The Stork. The Blue Angel. Another iron curtain joke. Cafe society was still alive here, lounge lizards and all.

“They’re terrific, aren’t they?” Bielak said, nodding toward the mime troupe. “I never get tired of them.”

“You’ve seen them a lot?”

“Well, there aren’t so many clubs here.” He took a drink, standing closer. “I see you met one of our local celebrities.” Prodding. “At the concert. He didn’t introduce himself?” Insistent now, close.

Nick wasn’t sure what to answer. How would it be reported? But Bielak was waiting, his lips wet with drink.

“Yes,” Nick said finally. “I thought he was in Moscow.”

Bielak nodded, his air confiding. “He married a Czech. A bourgeoise.” The term threw Nick, some bizarre leftover from the old party meetings, those hours of dialectic and self-discipline. But Bielak didn’t hear it as an anachronism, and when he saw Nick’s look, he said, “Of course, not now.”

“I didn’t know,” Nick said vaguely.

“What did he say? I’d be curious.” He had leaned even closer, his whole body a kind of insinuation.

“Not much. How I liked the concert,” Nick said. But this wasn’t going to be enough. “I think he was a little disappointed that I didn’t recognize him.”

“Too much?” But Bielak seemed pleased. “Yes. He used to be famous, you see.” He shook his head. “Nobody remembers, do they?” Delighted somehow, a press agent watching a falling star.

“We have to go,” Nick said, signaling to Molly.

“So soon? They’re not finished.”

“No, but I am. We have to be up early.”

Why had he said that? Bielak, however, was smiling, amused.

“Young people,” he said. “In my day, we could dance all night.” So he had watched. Was still watching. “One more drink?” Was it possible he just didn’t want to go home? The empty apartment.

“Thanks, some other time. Molly?”

Bielak nodded and raised his fingers from the glass in a kind of wave. “I’ll see you around,” he said, his voice pleasant, not sinister at all.

Back in the street, Nick was rattled. A chance meeting? What if he was around tomorrow? In the lobby. At the station itself. As they walked along the street he found himself looking to the side, expecting shadows to move. It’s simple, his father had said. But it wasn’t. A quarrel with Molly? Who would believe it? Not Bielak, making his rounds. Nobody just got on a train, not here. Why risk it, all of a sudden? He started picking the story apart, uneasy.

Later it was worse. When Molly fell asleep curled next to him, he stared at the street light on the ceiling, looking for microphones that might not be there. You always brought me luck. Something was wrong. And what would Vienna be like? More cat and mouse. He wanted to turn his mind off, sleep, but instead he lay still with dread, awake with night fears, the ones that didn’t even have names.

He shaved without running the water, careful not to wake her, and dressed quietly in the dim light. He put a few things in the small canvas bag, then crossed over to the desk and took her passport out of her purse. Both of them were leaving, a better story. No quarrel. She’d be late. When the floorboards creaked he stopped, but she didn’t move, a mound under the covers. He turned the knob slowly, so that when he finally closed the door behind him there was only a soft click. In the hall a maid stared at him as if she’d caught him coming out of someone else’s room, but he nodded and whispered ‘Dobre ráno’ when he passed, just an early bird. He went down the stairs. The lobby was empty, but just in case he paused and took out his street map, a tourist plotting his walk, his head still down as he passed through the revolving door.

It was early, just a few people on their way to work, but he turned off Wenceslas at the first corner and took a series of side streets to circle back to the bottom of the square. Nobody was following. Near the Powder Tower he caught a tram, and watched out the window as it traveled back across Wenceslas, past the hotel, the doorman yawning. He walked to the university and headed left toward the station. The back streets, oddly, seemed less safe, without a crowd to hide in, but he kept going, one more deliberate wrong turn, then a glance at the map, another street, and he was there, the creamy art nouveau facade, vaulting shed behind, Wilsonova Street half filled now with sleepy commuters. Policemen stood near the doorways, looking bored, guns at their sides. No one looked at him.

The woman at the ticket booth said something in Czech and repeated it until Nick tried his little bit of German: ‘Zwei nach Wien.“ She took the passports and examined them, checking against sheets in a looseleaf binder, then leaned forward to look to his side, evidently expecting to see Molly. When she spoke Czech again, he gestured with his hands to indicate that she was following. The woman said something again, then, seeing his blank expression, gave it up, shrugging and stamping the tickets. Life was too short, even here. She took the money, grumbling at having to make change. ”Pĕt.“ He stared and she repeated it, then grudgingly took a slip of paper and wrote ’5‘, pointing toward the platforms. He nodded, thanking her in German, and moved away, putting the tickets in his pocket. That was it, as easy as he had said.

He walked across the hall toward the platforms, glancing around. Coffee stalls, newspapers. Any station. He found the men’s room. Was there another one? A man stumbled out, obviously drunk, still zipping his fly. Inside was a row of stalls and sinks, urinals against the wall. He stood for a minute, too nervous to pee, then opened the door to the first stall. He couldn’t leave the ticket yet, not for an hour, but there was a shelf, easy.

He made a half-circle through the hall to make sure it was the nearest toilet, then bought a coffee, wishing he hadn’t come so early. Would the teller keep an eye on him? The newspapers were Czech. Rudé Právo, Red Truth. He walked out onto the empty platform, feeling conspicuous, then sat on one of the benches near the gate where he could see both platform and waiting hall. Where would his father be? There was nowhere to hide here. He’d walk straight to the men’s room. Nick would follow. In an hour he’d be gone.

He had nothing to read, and in any case English might be noticed, so there was nothing to do but smoke and look at his watch, a pantomime of waiting. A soldier came up, machine gun pointing down, and spoke. Nick froze. Was he asking to see his papers? Then the soldier repeated it and made the sign for a match and Nick, grateful, handed him the disposable lighter. He looked at it curiously before he passed it back, an artifact from the West, then moved on to the next platform. But whom was he guarding? The hall was deserted except for the grim commuters, and Nick wondered what it had been like before, loudspeakers announcing the overnight expresses, wagons-lits connecting Europe. Now nobody went anywhere.

A man in a hat and a boxy suit, carrying a satchel, walked out on the platform. One passenger, at least. Nick followed his shoes. Not Western. Maybe a businessman heading back to Brno. Did the train stop before Vienna? There must be a border check, a customs search, rifling through the bags of the anxious Russian Jews. Too busy to bother his father. A cleaning man in a blue smock swept his way nearer, looking over at him, interested. Nick got up and went to the men’s room again.

This time he could pee. He was alone, he could leave it now, but what if someone else found it? Why hadn’t they set an exact time? He washed his hands and went back to the bench. A suburban train had pulled into the next platform, and people were moving off as if they were still asleep. Otherwise, it was the same as before, the soldier circling, the man in the suit waiting. Another man was on the platform now, pacing. Nick sat looking from one to the other. They all moved in silence, almost orchestrated, like the Laterna Magika. A train attendant checking a pocket watch walked out to the end of the platform. Any one of them could be someone else, waiting for his father. Two older women and a young man, one suitcase. Who was leaving? The boxy suit moved back toward Nick’s bench, glancing over at him, then circled back. Would they know his father by sight? He used to be famous. Molly would be up now, wondering where he’d gone. But he couldn’t leave a note. He’d get a taxi back.

When he saw the train coming in he began to panic. This was cutting it close. A ten-minute layover. But maybe that was right. A sleight of hand, quick. Where was he? There was a slow screech as the train stopped, doors banging open, a few people getting off, handing a suitcase down through the window. The people waiting on the platform began to move toward the train. He couldn’t just stand there. Had he missed him somehow? He went back to the men’s room. Maybe he was waiting.

The first stall was closed, feet visible underneath. He stood at the sink. It would have to be now. The whistle would go any minute. If he came now, Nick would have to hand it to him, tell him to run. He turned off the tap. Come on. And then it occurred to him that the feet were his father’s, holding the stall. Of course. He’d been waiting all this time and now was late, Nick’s fault. Nick darted over and pushed open the door, ready to hand him the ticket. A curse in Czech. A man, his pants down around his ankles, glared in surprise, then yelled. “Sorry,” Nick said, yanking the door closed.

He ran out of the room and stood at the head of the platform. He’d have to pass this way, see Nick, not bother with the men’s room. Just take the ticket and go. Nick looked around, frantic, then down at his watch. Not this close. It was stupid. They’d notice. The boxy suit and the pacer were gone, settled in the car. Only the attendant was now on the empty platform, looking at him. Nick turned to the waiting hall. He’d be running across the room now, late, accidentally bumping into Nick, snatching the ticket before anyone could see. The soldier was coming back, smoking again. Then Nick heard the whistle and jumped, swiveling his head between the train and the hall. The soldier looked at him. The train was beginning to move. There was no one near, no one running. Nick looked at his watch–what else did you do when someone was late? When the soldier came up to him and said something, Nick turned his palms up and shrugged. She had missed it. Then he turned and saw the train sliding out, the attendant waving as it passed him, faster now, on its way to Vienna.

He stood for a minute, not sure what to do. The soldier was still looking at him. Play it out. The story was everything now. He’d wait for her. He arranged his face, concerned and annoyed, as if he still expected to see someone walk through the hall. He stood against the wall, giving it a few minutes, waiting for the soldier to move away. Then he picked up the canvas bag and headed toward the door, away from the ticket windows. His father would never be late. Something had happened again. For a second Nick was angry–why put him through this? Was he supposed to go back to the hotel, wait for the next plan? But all this was just pushing away the dread. He saw his father’s face outside the concert hall, tense with worry.

Outside, he got into a taxi. If something was wrong, he should avoid him, wait for the right time. But he couldn’t.

“Namesti sovetskych tankistu,” he said, almost blurting it out. The driver looked at him–had he mispronounced it, or was it too unlikely a destination?–but put the car in gear. Nick lit a cigarette, trying to calm his shakiness, and watched the streets as they started down the hill. Red street nameplates on building corners, indecipherable. Bouncing across the embedded tram rails, fast, as if the driver felt Nick’s urgency. The river. Finally the tank at the foot of Holečkova, the empty traffic circle. He paid the driver and got out, unfolding his map and pretending to read it, part of the story. Then the taxi was gone and he was running up the long hill. No one ran in Prague. A workman coming down the hill scuttled to the side, avoiding him, flattening himself against the park wall. But Nick was running from his own demons now, not caring, the sound of ragged breathing in his ears.

The hill was steep and he stopped once, gulping, then started again, out of time. The apartment buildings appeared now, rising up against the park slope, set back from the sidewalk behind patches of banked lawns. White concrete balconies with their city views. He’d been lucky to get one. There was a black metal gate in the wall and Nick hung on it, jiggling the latch, then sprinted up the row of concrete steps leading to the building. Hell in the winter, slippery for old people. The entrance was in the back, at the end of the pavement. He raced up another series of steps, past some shrubs, the steep apron of lawn, a clump of pale blue shrub on the grass.

He stopped. Not a shrub. Pajamas. He walked across the lawn in slow motion, his chest heaving. The legs were twisted, probably broken by the fall, the face lying on its side, blood underneath, a dried streak at the corner of his mouth. Nick sank to his knees, staring. He reached out to feel for a pulse in the neck, but the skin was already cold. Then, without thinking, he moved his hand up, brushing back the thin hair, stroking the side of his head, smoothing away the lines of his skin so that the face seemed to him again the one he’d always known, not old, the same high forehead and wavy hair. With his other hand he lifted the head into his lap, still stroking it, rocking back and forth a little in a silent wail. His eyes swam. How could it hurt this much?

He looked up. Everything quiet. Was there no one to help? The balcony above them. Had no one heard? Or had there only been a thud, a dull thump onto the grass cushion? He rocked harder, cradling the head, heavy in his lap, oblivious to the dampness of the blood. When he glanced at the pajamas and saw the dark stain on the pants where his father had soiled himself, a final embarrassment, he held the head closer, comforting a child, telling him it didn’t matter. The quiet was unbearable, death itself, and he saw why people keened, made any sound to break the stillness so they weren’t swallowed up in it too. But a part of you went anyway, seeping out like blood. He stared down again at the face, smooth, irretrievable, somewhere else. The only thing he had ever wanted.

He didn’t know how long he knelt there, out of the world, but when he came back all his senses were there at once –the sound of a car passing in the street, the stickiness on his pants, the tingling surge of adrenalin fear. He should call somebody. Weren’t there neighbors? Gently he moved his father’s head, laying it back on the grass, and stood up. Maybe he shouldn’t be seen at all. But now what did it matter? He walked over to the sidewalk and followed it around the building to the door.

A jumble of nameplates, two apartments to a floor, Kotlar on the top. He ignored the small elevator, afraid of being enclosed, and climbed the stairs, the landings bright through a wall of glass brick. Moderne. Instinctively he raised his hand to knock on the door, but who would be there? Then he saw that it was already ajar, as if someone hadn’t closed it properly. Who? He pushed it quietly and stepped into the chilly apartment.

“Anna?” he called out, hearing nothing but the sound of a clock. He looked around the room–low Scandinavian furniture, bookcases, everything in order. The sliding door to the balcony was closed. He opened it, stepped out, and looked down. The body was still there, slightly to the right. He saw then that the balcony extended along to the next room and that the door there was open. He moved toward it, stopping when he saw the marks on the painted rail. Here? But his father had been barefoot, in pajamas, nothing to scrape against.

The bedroom was a mess, covers flung back, pillows scattered, as if he’d got up in a hurry. The night table was upright but at an angle, some pill vials and a book knocked to the floor, the lamp pushed near the edge. The desk chair was pulled back, out of place, where someone would bump into it in the dark. The desk wasn’t ransacked, the drawers still in place, but somehow disheveled, at odds with the neat living room.

He stood for a minute, imagining how it might have been. The sudden impulse in bed, knocking against the night table as he got up, staggering (drunk?), bumping against the desk, yanking the chair out of the way, the rush to the balcony, and over. Soiling himself in the terror of the plunge. None of that happened. It would have been deliberate, planned out like everything else. A note. Nick looked on the desk, moving some of the papers aside, and then stopped. You weren’t supposed to disturb the scene of the crime. The phrase struck him, another adrenalin surge. That’s what it was, wasn’t it? He looked at the room again. Another phrase: signs of struggle. Someone pulling him off the bed, dragging him, knocking against the furniture. Had he screamed? Nick leaned against the desk, lightheaded. Had he begged them to stop, fought back, one final swing, knowing his luck had run out? But no one had heard. The body was still lying there, unreported. Nick imagined instead a hand clamped over his mouth, muffling him, his arms thrashing as they forced him out, an old man, so terrified that he went in his pants.