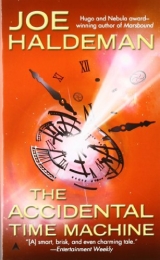

Текст книги "The Accidental Time Machine"

Автор книги: Joe William Haldeman

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

The ground was a jumble of broken metal and rock. La landed gingerly and put the ramp down. “Here you are. My part of the bargain.”

“No. You go down first.”

“Matthew, I’m an electronically generated image. What difference does it make whether I’m up here or down there?”

“I’m not sure. But it’s like you’re a component of the ship. When you’re outside, you have less power.”

“That’s very scientific.”

“Like a machine that only works if one person pushes the button.” He kept the pistol where it was and made a sideways gesture with his head.

La shrugged and walked down the ramp.

Matt worried the time machine out of its bracket and freed the alligator clip. “Are you okay?”

“I’ve been better.” Martha touched her breasts gently. “That was . . . you weren’t going to . . .”

“I wouldn’t, no. Let’s go down and see what happens.” Matt kept the pistol trained on the machine as they walked down the ramp. The air was cold but still, and smelled clean.

La was standing there with her arms crossed, not quite tapping a toe. “So how long will it be before Jesus comes to save you?”

“He wasn’t Jesus last time,” Matt said. “More like Saint George, looking for a dragon.”

“Well, if it’s me, here I am.” She looked over their heads. “And here he is. If I’m not mistaken.”

A shimmering globe half the size of the ship was descending. When it touched the ground, it disappeared like a soap bubble. Six men, or manlike creatures, stood where it had been.

Four of them seemed to be human. The one with the pear-shaped head had scales for skin. The other’s features were not fixed; it had two or more eyes and a recognizable mouth, but they constantly disappeared and reappeared elsewhere.

“Hello, Matthew. Martha.” Their savior still had a Jesus beard, but, like the others, was draped in what looked like mail. “Martha, if you would, please go back into the ship and get a day’s worth of food and water for you both. And anything else you want to take back.” She hurried back up the ramp.

“La. So you want to go all the way up.”

“That’s right. The heat death of the universe.”

“I can do that for you.” He held out his hand. “The machine, Matthew?”

He hesitated. “We won’t need it anymore?”

“Not unless you want to go with La. Believe me, the future doesn’t get any better on Earth. I’ve been there. It’s a closed book.”

Matt couldn’t figure out any way that the man might be betraying them. They were at his mercy anyhow. He handed it over.

“Thank you. You may call me, um, Jesse.” He sat down cross-legged, the machine in his lap. “You couldn’t pronounce my real name.”

His right forefinger became a motorized screwdriver. He undid the eight screws that held the cover on and set it carefully aside, slowly studying the wires that connected the top to the insides.

He gently tugged on a gray box inside the box, and it popped free.

“The virtual graviton generator?” Matt said.

“What else?” He pulled an identical-looking box from a pocket in his tunic. He pressed it home with a sharp click. “Voil а !”

“So what does that do?” La asked.

“Yeah,” Matt said.

Jesse looked at his companions and said something in a language that was mostly whistling. The human ones laughed. The pear creature made a noise like crab claws scuttling on wood. The other one’s mouth disappeared and reappeared.

“Neither of you would understand. You don’t have the math—you don’t have the worldview to understand the math.” He positioned the top cautiously and screwed it down tight. Martha came back with the bag, which was considerably heavier.

Jesse stood with balletic grace and handed the box to La. “Now the button works no matter who touches it.”

“I have only your word for that. How do I know it won’t explode?”

“You don’t,” he said cheerfully. “But you are the only entity here who’s not alive—not in any biological sense– and you’re worried about dying?”

“Dying is not the opposite of existing.”

“I guess you’ll just have to trust me. As these two must.”

She took the box and looked at Matt. “It’s been interesting. ” She walked up the ramp with it, and less than a minute later, the ship disappeared with a faint pop.

“She’s on her way?” Matt said.

Jesse nodded, looking at the space where the ship had been. “I’ve never tried to go so far up. I assume the thing will keep working, but asymptotically.”

“She’ll get closer and closer, but never quite be there?”

“As she must have known. As long as she can still push the button, the show isn’t over. By definition.”

“Why did you help her?” Martha said. “And why are you helping us?”

“With her, it’s just courtesy. People, or nonpeople, get stuck in time. Other time travelers unstick them.

“With you, it’s not so altruistic. If you, Matthew, were to die before going back, this whole bundle of universes would disappear.”

“If I hadn’t discovered the time machine?”

“Well, you didn’t actually ‘discover’ anything, did you? You just used a component that was faulty in a dimension you can’t even sense. Like the family dog accidentally starting the car. Not to be impolite.

“We’ve sent you back before.” He rubbed his brow. “Words like ‘before’ and ‘after’ become inadequate. But we have sent you back to 2058 to bail yourself out, a large number of times. We know that because we’re still here. All of us are your descendants, in a way. If time travel hadn’t started in your time and place, we wouldn’t exist.”

“Even the, um . . .” He made a helpless gesture. “The aliens?”

Jesse said something in the whistling language. The one with the scales made his crab-claw noise and the other one’s face filled up with eyes. “They’re at least as human as you are.” Martha smiled at that.

“Sorry. Sorry.” The two strange ones bowed. “So do you have a time machine?”

“The six of us area time machine.” He pulled out the virtual graviton generator. “You have to both be touching this, for calibration. It will send you back to where Matt first pushed the button.

“But there’s something like an uncertainty principle involved. We can send you back to the exact time or the exact place, but not both.”

“Time, then,” Matt said. “We can find our way back to Cambridge.”

“Well, no. Not if you appear a mile under the sea, or inside a mountain. I’d choose place, if I were you.

“You might be only a few seconds off, or you might be years. We have no control over that. Was your lab on the ground floor?”

“It was, yes.”

“If it weren’t, you’d appear on the bottom floor beneath it. If you’re in a future or a past where the lab doesn’t exist, you’ll appear at ground level where it was or will be.”

“What if I meet myself and say, ‘Don’t push that button’? ”

“It won’t happen. You can’t exist, as your former self, in this universe. When we’ve sent you back to 2058, your copy automatically showed up in a time when you were in transit, and left before you reappeared.”

Matthew rubbed his chin. “I can do anything I want? I could reinvent the time machine?”

Jesse paused. “We know that you haven’t. You could try; the dog could start the car again. But it wouldn’t be smart; you’d be well advised not to put yourself in the public eye. You’d look very suspicious if someone investigated your past. If you claimed to be a time traveler, you’d probably be locked up.”

“Even if we appear in the future?”

“Even so. You won’t have existed; there would be no Marsh Effect.”

“At least the bastard won’t win a Nobel Prize.”

“You never know.” He handed the gray box to Matt. “Are you ready?”

Matt looked at Martha. She managed a weak smile and nodded. She touched the box and he folded his other hand over hers. She did the same.

“Good luck,” Jesse said. The others murmured, whistled, and scraped similar sentiments.

There was no interlude of gray. One moment they were in the Antarctic waste, and the next, they were ankle deep in mud. It was a cool fall day. A few hundred yards away, workmen were toiling at the edge of the Charles River, building a seawall.

“Oh, my God,” Matt said. “MIT hasn’t been built yet.”

A policeman in a blue uniform walked toward them, swinging a billy club.

“The more things change,” he said, “the more they stay the same.”

21

The cop had a silly-looking tall bowler hat, a walrus moustache, and an amused expression. “And you’d be from the circus.”

“That’s right, Officer,” Matt improvised. “We’re truly lost. Could you direct us to Kendall Square?”

“You’re on the right track.” He pointed with his club. “Goin’ through this mud’s a bad idea, though. It gets deep. You go on back to the bridge, go right on Massachusetts Avenue there, and right again on the second street. It’s a longer walk but won’t take half the time.

“So you’re acrobats?”

“Tightrope walkers.” That was sort of how Matt felt.

“What are you doing on this side of the river? Is the circus coming to Cambridge?”

“No, no—we just got lost,” Matt said, Martha nodding emphatically.

The officer scowled in a comical way. “Well, you know you should put on some actual clothes.” He stared frankly at Martha and chuckled. “Miss, another policeman might arrest you for immodest dress. Allow me instead to express my gratitude.” He touched the bill of his hat with his billy club. “Just a word to the wise, you understand.”

He turned and walked away, whistling.

“That was close,” Matt whispered. He took Martha’s arm and steered her toward the bridge.

It looked brand-new, with forest green paint. In Matt’s time it had been an antique; Martha remembered it as being partly collapsed in the middle, from a bomb in the One Year War, with horse traffic taking turns each five minutes, in and out of Cambridge.

“Where are we going to get clothes without any money?”

“I’m not sure,” Matt said. “A church?” He knew the way to Trinity Church, but wasn’t sure whether it was Catholic or Protestant—just that it was old and beautiful. It took them about twenty minutes to walk there, disrupting traffic, attracting stares and the occasional rude comment, and meanwhile they made up what they hoped would be a reasonable story. They had come into town to audition for the circus, but while they were practicing, someone stole their luggage, along with his wallet and her purse. They didn’t need nice clothing; just something to cover them up.

Matt had been hoping for nuns, and was surprised to find that Trinity had a few, even though it was Episcopalian.

A calendar said 1898.

The nuns received their story with a grain of skepticism, but rummaged through the poor box and found worn but clean clothes that sort of fit, which they would loanthem until they were gainfully employed. The nuns also gave them a loaf of fresh bread from their kitchen, which they gratefully took down to the water’s edge, where there were park benches looking out over the river. They were more or less across from where MIT would start growing in a decade or so.

“I like this dress,” Martha said, rubbing the fabric. It was a burnt orange long-sleeved affair that covered her from ankle to neck. “Are you okay?”

“Fine.” He had faded patched blue jeans and a worn gray flannel shirt. “I’d rather see more of you, though. Seems funny.”

“You’ll get used to it.” Martha had packed two bottles of wine and two cups, which were made of some unbreakable polymer but looked like glass. They might have some trouble explaining a bottle of wine that cooled when you unscrewed the top, and stayed cold, not to mention the plastic containers of fish salad that did the same when you pinched a corner. So they didn’t invite anyone to join them.

Money was the first problem, of course. “Could we sell the gun? We don’t need it.”

“It has only one bullet left, anyhow. But I don’t know whether they made this kind in 1898. The cartridge says ‘.38 Special,’ but I don’t have the faintest idea what made it special. The taxi driver probably wouldn’t be carrying around an antique.” Though it did look old and worn.

“The Lincoln note ought to be worth something, but the 2052 letter of provenance, the guarantee that it’s authentic, is worthless, of course.”

“The sexual teaching box, too,” she said seriously.

“Probably get us burned at the stake. If they still do that here.”

He sat back and sipped on the cup of wine. “Once we do have some money, I could multiply it easily by betting on sure things. Like, I don’t remember who was elected president in 1900, but it’s almost certain that I would recognize his name and not his opponent’s. Likewise, investments in new companies that we know are going to succeed.”

“Invest in groceries first, though, and a room. I wonder how you go about getting a job?”

“Newspaper. If they have want ads in 1898. Advertisements for things you want.”

To find a free newspaper, they trudged back up the hill to the Boston Public Library, across the way from Trinity Church. It was a huge granite structure, still new enough to shine.

There were newspapers on spindles in the reading room, and a cigar box with scrap paper and stubs of pencils.

Not much work for quantum physicists, since Neils Bohr was only thirteen, and Planck’s Nobel Prize was a generation away. He found offers for laborer, roustabout, stable hand. None too exciting.

He struck pay dirt, so to speak, in the third newspaper: a janitor needed at MIT.

“Look at this,” he whispered. It had a Boylston Street address, not far away. “I knew the ’Toot was in Boston for a while before they moved it across the river to Cambridge.”

“Let’s go try it. Maybe they’d have something for me, too.”

It didn’t take long to walk down to the west end of Boylston, and there it was, an imposing four-story building in Classic style. Matt could visualize what this part of Boylston would look like in 150 years—this wonderful building replaced by boutiques and a two-story ranch bar.

But that was then, and this was now. So to speak. That was yet to be, and this was back then.

They went up the slightly worn marble steps into a large hall punctuated with Doric columns. To the left was the president’s office; to the right, the secretary’s. That might be the right choice.

Matt paused before the door. “I don’t know what’s proper,” he whispered. “Do I open the door for you, or precede you?”

“You first, Professor.”

He stepped in to confront a stern-looking woman in a starchy gray-and-black dress. “May I help you.” Her tone said she was sure she could not. Matt, accustomed to dressing like a graduate student, was suddenly aware of how poor he looked.

“You, uh . . . there was an ad in the newspaper for a janitorial job.”

“Janitorial?” A tall man stepped out from behind a bookcase. He looked like the old twentieth-century comedian John Cleese. “That’s an odd locution for one who aspires to be a janitor.”

“Professor Noyes, I can—”

“No, please, Vic.” He looked at Matt with his brow furrowed. “You aren’t from Boston.”

“No, sir. Professor. I was born in Ohio. Matthew . . . Nagle.”

“You sound educated.”

He took a deep breath and started to lie. “Home education, sir, and the library in Dayton. Science and mathematics. Someday I’d like to take some courses at MIT.”

Professor Noyes raised an eyebrow. “That is its name, of course. Most people call it Boston Tech.”

Matt thought it safest just to nod.

“What kind of science are you interested in?”

Local asymmetries in gravity-wave induction probably wouldn’t do it. “Physics, some astronomy.”

Noyes smiled. “I’m a chemist, myself. You know the atomic weight of hydrogen?”

“One.”

“The brightest star in the constellation Orion?”

“Betelgeuse.”

“If x squared plus two equals 258, what is x?”

“Plus or minus sixteen.”

“The integral of e to the x?”

“That’s e to the x. Plus C.”

“Miss Victoria, I think he knows enough science and math to be a janitor here.” He smiled at Martha. “And you, ma’am?”

“I don’t know any of that, sir. I’m Martha Nagle.” She swallowed. “His wife.”

Matt tried not to react.

“We offer free classes for women, you know, in the evening. You should join a few and show him science isn’t all that hard.” He lifted a top hat off a rack by the door. “You can take care of it, Vic?”

“I will, sir.” She watched him leave, smiling. “Goodbye. ” There was no “sir” in her voice.

After the door closed, she pulled a sheet of paper, a printed form, out of a drawer, and carefully dipped a pen in a crystal inkwell. “Matthew Nagle—is that G-L-E?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Middle name?”

“None.” She wrote his name in a precise Spencerian hand.

“Birth certificate or some other identification?”

“That was in our luggage . . . which was stolen. Off the train.” Hoping MIT and Trinity didn’t compare notes.

“You’ve notified the police?”

“At the station. We’ll check downtown tomorrow. It seemed prudent to start looking for employment. My wallet and Martha’s purse were in there, and we’re—we have no money.”

“Really. It’s usually good advice, to put away your purse before you go to sleep on a train. But they took everything?”

“Everything,” Martha said.

She dipped the pen again. “Any address here?”

“No.”

She left the pen in the inkwell and opened a bottom drawer and lifted out a metal box. “You didn’t ask what the salary would be.”

“I assumed it would be fair.”

“I don’t know. This is not my usual function.” She opened the box and counted out ten silver dollars, then added two more. “I’ll make a note of this advance. Come in tomorrow at eight and I will introduce you to the supervisorof maintenance. You don’t mind working under the supervision of a Negro?”

“No. Of course not.” Vic slid the stack of coins over. “Thank you. This is . . . extraordinary.”

“Boston Tech is extraordinary.” She gave him a rueful smile. “I am President Crafts’s first line of defense, so to speak, and as such I am supposed to be a good judge of character. As I judge your character, there is a small chance you will take the money, and I’ll never see you again.”

“I—”

“There’s a larger chance that someday you will be one of my bosses. Now go and find a place to stay. The rooms on Commonwealth and Newbury are nicer; the ones on Boylston are cheaper and closer.”

“Thank you.” The twelve cartwheels rattled a heavy cascade into his pocket.

“Martha, this isn’t Ohio. They won’t let you stay with your husband unless you have a marriage license. Or at least a ring.”

She reddened, and evidently decided not to make up a story. “We’ll take care of that.”

She nodded perfunctorily and put away the cash box. “It was when you said, ‘Plus C,’ Matthew. Most of his undergraduates would just say ‘e to the x.’ ”

They walked all the way to the street in silence,before Matt brought it up. “You don’t have to marry me. We’ve only known each other—”

“Three million years or so.” She took his arm. “Matthew, in my time, love isn’t part of marriage. Sometimes it happens, and some people are happy and some are jealous. But our husbands are chosen by our parents, and we make the best of it.

“I think I love you, which is a better deal than I would have gotten at home. And really, in the time we’ve known each other, these few million years, we’ve done more together than most married couples ever do.”

He chuckled. “That’s true. Been more places, had more adventures.”

“Except the one.”

He stopped walking and looked her in the face. “I wonder how much a marriage license costs. I wonder whether we could get one today.”

22

Matt got a hundred-dollar bill for the Lincoln notethat had cost him ten thousand in 2079. He bought nice wedding rings for both of them, and had enough left over to buy some decent clothes and a fine dinner at the Union Oyster House, which they both remembered from their respective futures.

Matt was surprised to find that he enjoyed being a janitor, the slow and steady predictableness of it. But he wasn’t a janitor long. He took evening classes for one year, and of course drew attention.

The Lowell Institute funded free evening “lessons” in various science and engineering disciplines, and mathematics. His teachers in mathematics and physical science were amazed at the erudition of this autodidact from Ohio.

In Matt’s second year, he was hired by Lowell as a night instructor in algebra and calculus. They also gave him a stipend so he could quit his day job and pursue a degree.

Of course he had a huge unfair advantage over other students. He had the “foresight” to study German intensively, and when in 1900 Max Planck published Ь ber eine Verbesserung der Wienschen Spektralgleichun, the paper that eventually led to quantum mechanics, Matt was the first person at MIT to read it and explain it to others. In 1901, he earned his first physics degree, and his second in 1902. MIT sent him to Harvard to get his doctorate so they could ask him back to teach (even then, there was a tradition against an institution hiring its own new Ph.Ds). At Harvard he pored through Annalen der Physikand was the first to note the importance of Einstein’s four papers in 1905, including Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter K ц rper, which changed the world forever and gave Matt an impressive doctoral dissertation.

This was indicative of his life’s strategy. He could have beaten Einstein to the punch; as an undergraduate in 2050 he had been required to go to the whiteboard and derive the Special Theory of Relativity from first principles. But he couldn’t afford to become famous. People would be curious about his past, and find out that he had none.

Martha went to night school as well, working days as a chambermaid in the Parker House Hotel, and eventually got a degree in general science. Her accomplishment was more impressive than Matt’s, though only Matt knew why. She worked as an insurance analyst for two years, then had the first of their four children, and retired.

In 1915, the last year before MIT moved across the river, Matt made full professor. The next year, while the physics department was settling into the mudflats of Cambridge, Matt read Einstein’s Die Grundlage der allgemeinen Relativit д tstheorie, the Annalenarticle where he first described General Relativity. Of course, everyone had his eye on Einstein by then, but to most scientists the mathematics behind General Relativity was new and difficult. Not so to Matt; he’d had tensor calculus in 2051, and boned up on it in 1916, before the paper came out.

He was one of the most popular professors at MIT, for the students, though he was a puzzle to the faculty. He published papers with acceptable frequency, but they were “solid” work rather than brilliant—whereas in person he often wasbrilliant, making connections that no one else saw. In conversation he was years ahead of his time; in publication he was not. Carefully not.

Their marriage was so conspicuously happy that even their own children were impressed. It seemed as if all of life was amusing to them. Of course, no one knew that they were a conspiracy of two. Perhaps all great loves are that: a secret that can’t be shared.

Among his mathematical skills was arithmetic. He knew that his mother would be born in 1995, and so there was no chance that he would live long enough to go to Ohio and see her as an infant. Perhaps that was a good thing.

Matt lost Martha in 1952, when she was seventy-four. A professor emeritus at eighty-one, on his way back from the funeral he saw the headlines about the H-bomb the U.S. had exploded in the South Pacific. He went to his office that day, and as a way of dealing with grief he tried to spread hope: This is not the end of the world. The world is big and resilient.

To his own surprise, he lived another seventeen years. In his final hours, he watched the ghostly images of men jumping around on the Moon. His last words were enigmatic: “I’ve been there, you know. It’s much like Earth.”

His story doesn’t quite end there. The year after Martha died, he had hardly noticed when his seventeenth great-grandchild was born, a girl named Emily. She married Isaac Marsh in 1975, and in 1999 they had a son, Jonathan.

In 2072, Jonathan Marsh would be given the Nobel Prize in physics, for discovering a curious kind of time travel.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Back in 1971, when I started writing The Forever War, I needed a way to get soldiers from star to star within a human lifetime, without doing too much violence to special and general relativity. I waved my arms around really hard and came up with the “collapsar jump”—at the time, collapsar was an alternate term for “black hole,” though I was unaware of the latter term. (Scientists now use “collapsar” in referring to a specific kind of massive rotating black hole.)

Years later, working from actual science rather than a novel’s plot requirements, physicist Kip Thorne came up with his “wormhole” theory that did the same thing, to my delight. I never thought it could happen again, but with this novel it did.

Casting about for some reasonably scientific mumbo jumbo to use for a time machine, I settled on gravitons and string theory. Nobody has ever seen a graviton, so I was pretty much home free on that, and normal people can’t understand string theory, so that was fair game, too.

When I was about halfway through the novel, though, an article in New Scientistpointed me to a paper by Heinrich Pдs and Sandip Pakvasa of the University of Hawaii, and Vanderbilt’s Thomas Weiler, “Closed Timelike Curves in Asymmetrically Warped Brane Universes,” which indeed uses gravitons and string theory to describe a time machine. My jaw dropped.

It’s a truism of science fiction that if you predict enough things, a few of them are going to come true. But this particular phenomenon seems to be of a different order. It’s not that I have any special scientific credentials, just an old B.S. in physics and astronomy. What I think it actually demonstrates is that if you wave your arms around hard enough, sometimes you can fly.