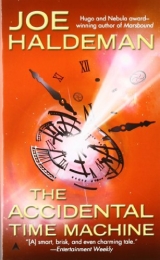

Текст книги "The Accidental Time Machine"

Автор книги: Joe William Haldeman

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

You need this woman, this machine, La. But never trust her. Remember, she cannot die. Think of how that makes her feel toward you. Think of what she might do to you.

Don’t say anything to Martha. She will see me, too. That’s why I have taken this appearance. You are both having the same dream– which is not a dream. But it’s the only way I can talk to you without La knowing.

La sees everything you do and say. Be careful. She could leave you behind. She has no need for the backward time machine.

I will find you in whatever time and space. Never let La know I am available.

He was gone. “Whatever time and space?” What was he? Not the actual Jesus. If there was an actual one.

Matt lay awake for twenty or thirty minutes. Then he felt in the dark for the robe hanging on the door, put it on, and went into the sitting room to get a glass of wine. Just before he turned on the light, he knew he wasn’t alone.

“Matt?”

“Martha.” He stepped past her and touched the bottle of white wine. It was still cold, automatically refrigerated somehow. “Couldn’t sleep.”

"Me . . . me neither.”

“Care for some wine?”

“No, not really.”

He poured himself half a glass and looked into her face, one look, then away. He’d never seen such intensity. Faith or fear or confusion, whatever.

“Disturbing dreams?”

“Not disturbing. Strong, but not disturbing.”

“Me, too. Understandable. A lot’s happened in the past twenty-four hours.”

She was wearing the same kind of robe. She gathered it around herself and tied the sash belt tightly. Not changing expression: “People can sleep together without adultery? I mean, without being together to make children. Does it have to happen?”

“No. Not unless . . . no.”

She took a deep breath and exhaled. “I’ve never slept alone, and I’m a little afraid. If I could sleep with you, I would be grateful.”

“Sure. I understand.”

"I could just take some covers into the corner, like in Cambridge. ”

“Absolutely not. It’s a big bed. You can have half.”

She nodded with her eyes closed. “Mine was too big for one. I was kind of lost without a bunch of sisters or students sharing it.”

“Come on. Let’s get some rest.” She touched his hand and smiled and preceded him into the bedroom. He turned off the light and got in next to her, carefully not touching. He heard her shrug out of the robe.

“Thank you, Matt. Good night.”

“Night.” He didn’t sleep for a while himself, resisting the magnet pull of her weight on the other side of the bed. Her womanly smell, the soft sigh of her breathing.

He had vivid dreams that did not involve Jesus.

It was a hearty breakfast. Matt and Marthahelped themselves to traditional fare, eggs and bacon and pancakes. La had a bowl of clear soup, just to be sociable.

“So what about our interrogators?” Matt asked. “Are they here yet?”

“In a sense. Only one of them is flesh and blood. The others are like me, projections. Most of them reside in orbit. So they’re as ‘here’ as they ever will be.”

Martha had only nibbled at a little pancake and egg. “You should eat more, dear,” La said. “The interview will take several hours; you’ll be famished.”

“I’m sorry,” she said. “It’s not reasonable, I know, but the word ‘interview’ frightens me.”

“Just people asking you questions,” Matt said helpfully.

She stared at her plate and pushed food around. “We have confession once a week. You tell a Father what you’ve done the past week that was wrong.”

“And he punishes you?”

“No, not normally. He makes sure you understand what you did, and if someone was hurt by it, tells you how to make that right.

“But if the sin is bad enough, you go for an interviewdowntown, at Trinity Church. Nobody is allowed to say what happens there. But I’ve seen people come back missing fingers or, once, a hand. Four or five years ago a man did something with his dog. They hanged the dog, then cut the man apart and burned his insides in front of him, while he was still alive. They kept him alive as long as they could, with medicine, while he watched, and they cut off his eyelids so he couldn’t close his eyes.”

“Shit. They made you watch that?”

“No, my mother wouldn’t let me go. But they left his body hanging on a stick for a year, downtown, along with the dog.”

Matt broke the silence. “We have a saying. ‘Yours is a world well lost.’ ”

“Was that Shakespeare?”

“Dryden,” La said, “1688. Shakespeare had been dead fifty-two years.”

“Most of my world isn’t that bad. But the interview was about the worst part.”

“Nobody will judge either of you in this one. Set your mind at ease. They just want to find out how you lived, what your world was like. Nobody will hurt you.”

“A lot to do in two or three hours,” Matt said.

La agreed. “It amazes me.”

Two valets led them downstairs and into separate rooms for the interviews.

In Matt’s room there was a comfortable-looking lounge chair beside a shoulder-high black box. It made mechanical noises while he obeyed the valet’s request to strip down and lie quietly.

A helmet slid over his head, and he felt it prick him dozens of places, not painfully. Then a wire net settled over his body, from clavicle to ankles, and stretched tight. Part of him knew he should be resisting.

He was maybe eighteen months old, crawling. Adults talked above him, but it was just pleasant noise, without meaning. Then someone shook him and yelled at him and laid him down on a blanket and roughly changed his diaper.

Then it started to accelerate, quickly sorting through the years of his childhood, picking out the most painful memories and replaying them in mercifully compressed time, or unmercifully concentrated time.

Then into middle school and high school, with all the fumbling experiments and excruciating embarrassments. College was almost a relief except when it was unbearable. Then graduate school and the wringer he’d been through since the time machine invented itself.

When he opened his eyes it was just a room again, and somehow he was dressed, but his mind was still spinning. He eased his head up and turned so his feet swung to the floor.

His mouth was dry, gummy, as if he’d been sitting with it open. “Water?”

The valet appeared with a tinkling glass of ice water. Matt drank half of it in three gulps, then sat panting. “How is . . . Martha?”

The image gestured and he saw a new door in the wall, an oak door with a bronze knocker. Matt crossed, limping a little, and knocked, and then knocked again. No answer.

He pushed on the door and it eased open silently. The room looked identical to his. She was on her knees at the end of the lounge, her palms together in prayer.

He cleared his throat slightly and she looked up at the sound and smiled. “Where did that come from? The door?” She rose to her feet gracefully and danced across the room to embrace him.

“Oh, Matthew! Wasn’t it wonderful?”

“The, uh, the interview?”

“It was so cleansing—it was like I was confessing to God Himself, and was forgiven.” She hugged him tightly. “The dream last night, and now this. I never will be able to repay you for bringing me here.”

Well, if you run out of things to confess, he thought, I’ll be glad to help you come up with something new.

“I’m happy for you,” he murmured. “For me, it was not so pleasant.”

“Why not?”

“Maybe I’m not used to confession.” He laughed. “Maybe because I’ve never hadone, and I had a lot of sin stored up.”

“That’s probably it,” she said. “You’ve done a lot more than I have, anyhow, and you’re pretty old.”

“Only twenty-seven,” he protested, but yeah, there was a certain amount of fornication, prevarication, and masturbation in those years. Was there anything in the Bible about dope? “And I can’t even remember the last time I murdered somebody.”

“Don’t joke about sin,” she said, but she was still smiling.

La appeared next to them. “We have some things to talk about before we leave. What to expect. But I suppose you want to eat first, perhaps rest.”

“I’m starving,” Martha said.

“Go back to where we had breakfast. If you tell me what you would like, it may be ready when you get there.”

“Bread and cheese and fruit,” she said. “Mild cheese.”

“I want a hamburger,” Matt said. “Two hamburgers. With everything.”

“Give me one, too, please.” To Matthew: “They’re horrible at school, like leather fried in grease. People were always saying how good they were somewhere else.”

“Well, that’s sure where we are now, somewhere else. Let’s go.”

The burgers weren’t ready when they got upstairs, but the breads and cheeses and fruit were laid out artistically. They did considerable damage to the display in the two minutes it took for the valet to show up bearing two plates.

They probably weren’t the best hamburgers he’d ever had, but they were the most welcome. Comfort food. But the meaning of “with everything” had changed over the ages: his burgers were topped with a fried egg, bacon, avocado, and a slice of pickled beet as well as the expected lettuce, tomato, and onion.

After the interrogation and heavy repast, they slept for several hours. Matt woke up to an empty bed. He dressed and went into the sitting room.

Martha was looking at the porn notebook, turning it this way and that. “When I picked this up, it had the strangest picture. But then it disappeared.”

“You have to hold it a certain way for several seconds. That’s to keep children from accidentally turning it on.”

“Hm. It looked like something children would be interested in.” She grasped it various ways, but didn’t get the right combination.

“There. You keep your left thumb there, and slide the right one halfway down.”

The picture flashed on, somewhat dim because the ambient light was low. It was vivid enough, though, with unconvincing passionate sound. “What’s she doing with his thing?”

“Um . . . it’s something people sometimes do if they’re in love.”

She nodded and studied it. “She doesn’t sound like she’s in love. She sounds hungry.”

In that context, something was about to happen that would be hard to explain. “Here.” He took the display and turned it off by placing thumbs in opposite corners. “They teach you about things like this in your Passage, I think.”

“That’s how they make babies?”

“Well, not exactly. But it’s related.”

She waved a hand in front of her face. “I don’t want to know, yet. If I’m not home in a week or two, maybe we can talk about it.”

“Sure. Be a good thing.” That set up an interesting array of conflicts. He could just leave her with the book and hope that the images would free her repressed sexuality. But she might find it so scary or revolting that she would completely retreat. He could step her through it as if she were a child, the birds and the bees—but the last thing he wanted to be was a father figure. Even an uncle figure.

Avoiding it would not be a good strategy, but being too direct could be a disaster. What if she drew a parallel from some Bible story like Bathsheba’s, and saw him as a seducer?

Of course, he did want to be a seducer, technically. He just didn’t want to be a bastard about it. Have her take the first step.

La rescued him by knocking on the door. Of course she would have been watching the exchange with the porn machine, and wisely didn’t simply appear next to them.

They sat on the couch, with La facing them. Matt poured two glasses from the still-cold bottle.

“If you went backward through time as far as we’re going forward, you would be back in the Paleolithic Era, in the middle of the last great ice age. People were huntergatherers, thousands of years before agriculture. Language would be very primitive, and even if we became fluent, it might be impossible to explain our situation to them.”

“I’ve thought about that,” Matt said. “About going into a future that’s literally incomprehensible to us.”

She nodded. “Where they would have to study usand invent a way to communicate. I’ve developed a few approaches to that situation.”

“Or there might be the opposite of progress,” Matt said. “Civilization might be a temporary state. We could wind up in the Stone Age again—after all, my last jump was only a couple of centuries, and the last thing I would have expected would be a return to medieval theocracy.”

“That’s not really fair,” Martha said. “We know about things like television and airplanes, but choose to live simply, without them.”

“I stand corrected. But we’re going a hundred times as far into the future, this jump.”

“But suppose you hadn’t detoured into that theocracy,” La said. “Suppose you had pushed the button twice and come straight here. Two thousand years later, but isn’t it less strange to you than Martha’s time and place?”

“It is. Most of the people I knew could make the transition easily, even enjoy it. My mother would go crazy here; shop till you drop.”

“Which is something we ought to be prepared for. The main reason I want to leave this place is that it’s so stable. One century is much like the next. We may step out of the time machine and find that nothing’s changed. The culture here is not just comfortable and stable; it’s addictedto comfort and stability. And there aren’t any barbarians at the gates; the whole world, outside of the isolated Christers, enjoys a similar style of life.”

“You could change it,” Martha said.

“You and the others like you,” Matt said. “If you left this world in the charge of people like Em and Arl, you wouldn’t have a utopia for very long.”

La laughed. “Don’t give me evil ideas. I’ve contemplated doing that, of course, and degrees of social engineering less extreme. But in fact the thou shalt notbuilt into me that prevents that is deeper than self-preservation is to your own selves. This civilization created me specifically to preserve it.”

“But you can run away from it,” Martha said.

“Only this way: leaving behind a perfect duplicate. It’s like a human committing suicide after making sure his family would be taken care of.”

She paused. “This jump might be literal suicide for you, of course. Or the one after, or the one after that. We might wind up in a world that man or nature has made uninhabitable.

“That was theoretically possible in your time, Matt. And Martha, the One Year War that created your world killed half the people on the East Coast—”

“No!”

“—and would have killed more if Billy Cabot hadn’t stepped in with his mechanical Jesus.”

“That’s not true.”

“He was one of us, Martha, so to speak. We knew it would take a miracle to save you people, so we provided one.” She waved a hand and the valet appeared. “Look. Jeeves, become Jesus.”

It did, but a more convincing one than the version in Cambridge a couple of thousand years before. His robe was old and soiled, and his face was full of pain and intelligence. No halo. He faded away.

“I’m not surprised you can do that,” Martha said slowly. “But it doesn’t . . . prove anything.”

La looked at her thoughtfully. “That’s true. If you believe in magic, it explains everything. Even science.”

Matt broke the awkward silence. “If we go far enough into the future, there’s no doubt we’ll eventually find an Earth that’s uninhabitable. Eventually, the sun will grow old and die. But before that, we’ll find a future that has reverse time travel. I know that I will come back from the future to save myself, back in 2058.”

“Someone who looked like you came back. But yes, that was the main evidence I used to convince the others—your other sponsors—that this wasn’t a wild-goose chase.”

“They’re people like you?” Martha said.

“Entities, yes.” She stood. “I’ll leave you alone to talk. You know how to get to the time machine?”

“Yes.”

“Meet me there when you’re ready. Your clothes and such are there; all you need is the box, the magic box. I’ll show you around, then we can go.” She disappeared.

Martha looked at Matt. “Do you think she really left us alone?”

“I’d assume not, while we’re in this place. Or in the time machine, for that matter.”

“I . . . I want to talk about Jesus. His various, uh, manifestations. ”

Matt nodded slowly. “When we get up into the future. The next future. When she’s not in control of everything.”

“But what’s to keep her from just materializing and eavesdropping on us there?”

“I think she can only do that here because the whole place—all of Los Angeles, and maybe most of the world– is all one electronic entity. That may be true twenty-four thousand years in the future, too, but shewon’t be in charge of it.”

“I only half understand that. It’s like when everybody used to have electricity in their homes?”

“Something like that, yeah. You couldn’t go out in the woods and turn on the lights.” But you could turn on a radio, he thought. “Pack up and go?”

She stood and picked up the bag. “We’re packed, Matthew.”

18

The massive door to the time-machine hangarstood open. When they walked into the cavernous room there was a quiet whir, and a ramp slowly dropped out of the belly of the machine. They walked up it, footsteps echoing.

La was waiting at the top of the ramp, wearing a one-piece suit that seemed to be made of metal. “Let me show you your room.”

Matt had expected something along the lines of a submarine or a spaceship, but it was actually roomy and austere rather than cramped and cluttered. It seemed bigger inside than outside; that was a good trick.

Their room was like a medium-small motel room, windowless, with a double bed and a closet. Two silvery outfits like La’s were laid out on the bed.

“You might want to put those on before we jump. They’ll protect you against things like bullets and lasers. A caveman could still knock you down with a club.” She motioned for them to follow her.

“Galley and head.” She opened a door to a small room with a table for two and lots of labeled drawers and a few appliances. The head was evidently behind a curtain.

“The rest here is the living room and control room.” There was a comfortable-looking couch and chair, almost identical to the one in their sitting room, and in the front, a setup that looked more like a proper time machine: three acceleration couches in a triangle facing a windshield. The front one had controls like an airplane’s; the two behind it were passenger seats, each with an elaborate safety harness. Of course the pilot wouldn’t need such protection, not being material when she didn’t want to be.

“This is where your box goes.” There was a rectangular inset next to one of the couches, just the right size. “When we’re ready to go, just strap in and push the button.”

“Okay.” He looked at Martha, and she made a “what next” gesture with her hands. “You could go ahead and put on the suit?” She nodded and went back.

“Weapons,” La said. “That pistol you have in your bag—are you skilled with it?”

“No, I just . . . found it. I don’t even know whether it works.”

“It will. There’s a pocket for it in your suit, on the right. Or I could give you something more sophisticated.”

“I hope we won’t need anything like that.”

“Let’s hope. But the pistol or . . .”

“I’ll stick with the pistol.” He’d actually fired one, a BB pistol, in high school, at a bad friend’s house.

He checked out the head, which had a toilet and cramped shower, and the galley—hundreds of prepackaged meals. What would happen, though, when they were gone? He asked La, and she said as long as there was a source of radiant energy, everything was recycled. That was a real comfort.

Martha came out, looking like a pulp-fiction heroine. She looked at herself in the head mirror and blushed, and plucked at the costume’s chest in an unsuccessful attempt to make it less revealing. “It looks fine,” Matt said lamely, trying not to stare.

“I’m sure youthink so.”

He went to put on his and found that it was similarly revealing. He looked like Buck Rogers with no airbrushing and a small beer belly. When he came out, Martha hid a giggle behind her hand.

“Might as well get started.” He put the box in place, attached the alligator clip to an obvious metal stud, helped Martha with her harness, and then strapped in himself. He had to take the gun out of its special pocket, above his right hip, and stuff it into a front pocket.

La sat in the pilot’s chair and put her hands on the wheel. “Ready when you are.”

“Okay.” Matt reached down and pried off the plastic dome. He pushed the button.

This time he was determined to be observant about the gray-out. But this time it was different.

The Jesus figure appeared again. There were three other people with him, but they were indistinct. “This jump should not be dangerous,” he said. “Just keep your wits about you and watch out for large animals. Go to Australia. ”

Jesus and his companions disappeared just as light came back—and motion, extremely. They were maybe ten meters above a storm-tossed ocean. Lightning crackled all around. The craft was buffeted up and down and sideways, then La pulled back on the wheel and they surged straight up, roaring and shuddering.

They broke out of the storm into bright sunshine, a solid swirl of storm cloud underneath them. They floated free, weightless inside their harnesses, until the craft leveled off into a ride as smooth as sitting in a chair.

“I’m going to head west,” she said, “and get out of this storm. We should be over land soon, Indonesia.”

“You can open your eyes,” Matt said softly.

Martha had both hands clamped over her eyes. “That was horrible,” she said in a tight, small voice. She was ghostly pale. Matt took one hand and it was cold and wet with tears. Her breath came in shallow gasps. She looked directly into his eyes. “But God told me not to worry.”

“Score one for God,” La said. “This craft could handle far worse weather.

“We aren’t getting any electromagnetic radiation from the shore.” She looked back at Martha. “Radio signals. There’s something farther south. But I’d like to land first and look around.”

“In the middle of that storm?” Matt said.

She pointed at the windshield and it became a radar screen. “Looks dry. We’ll be there in a few minutes.”

The clouds began to thin out, and soon they were flying high over a calm dark blue sea. Then land, a few rocks offshore, then a thick green jungle.

La followed the coastline for a minute. Pictures projected on the windshield showed magnifications of wildness. “No sign of civilization, not surprising.”

“They might have gone past the need for electromagnetic radiation,” Matt said.

“Sure,” La said. “What would they use instead? There.” A sliver of white beach appeared. She slowed and banked toward it.

They came in dead slow over gentle breakers and settled lightly onto the beach, well above the windrow that marked high tide. The ramp whirred down and settled in the sand with a solid crunch. A refreshing sea smell wafted up.

“Shall we?” La started down the ramp. Matt and Martha followed as soon as they could get untangled from the harnesses.

It seemed idyllic. It was warm, but the sea breeze was pleasant, the bulk of the craft shielding them from the tropical sun. Seabirds cried out above them.

Above the tall trees, a dinosaur’s head reared up and looked down at them, tilting in curiosity.

“Trouble,” La said. Matt had the pistol out just in time for a dinosaur the size and apparent disposition of a large mastiff. It came loping down toward them with a murderous ululation.

Matt fired, the sudden bang loud as a cannon, and the creature stopped dead. But it hadn’t been hit. It advanced more slowly, clawed hands out, jaws open, white mouth with too many teeth. Matt aimed and fired again, and the bullet blew through its lower jaw. A gout of red blood rib-boned out. It screamed and staggered backward, and then a flying reptile appeared and dropped on its back with a dull thud and ripped off its face. Three more of them landed, then a fourth and fifth, and they started fighting over the carcass.

“Defense,” La shouted, perhaps belatedly. Weapon barrels bristled out all over the ship, and they began firing, a screech and a sound like a sledgehammer hitting on a metal wall.

Whatever the nature of the weapon, it was effective. One after another, the flying creatures dropped to the ground, to die in convulsions.

One hopped, half-flying, straight toward them. It went over Matt’s head and scampered up the ramp. He fired one shot and it ricocheted off metal.

Behind him, Martha had fainted dead away.

“Get back!” La said. “Into the ship!”

“Are you crazy? That thing’sin there!”

“Not anymore. Carry Martha.”

He scooped her up clumsily and staggered up the ramp, waving the gun around.

When he got inside the ship, there was no trace of the monster except a slight smell of fried chicken.

La hurried up the ramp as it rose. It sealed with a clunk and a slight drop in air pressure.

He’d put Martha on the couch and was kneeling by her head. “You couldn’t have killed it out there? Before it—”

“No,” she said calmly. “It wasn’t me out there; just a projection of me. Once it came inside the ship, I was in total control.”

“I guess we’d better behave ourselves. In the ship.”

“Ha.” She looked through the windshield at the carnage below. Three new flying reptiles were tearing apart the corpses of their brothers, wary of each other in spite of the abundance of food.

“Those creatures didn’t come about by natural selection, ” Matt said. “Not in twenty-four thousand years.”

“I’d assume not; they were bioengineered. By whom and what for is the question.”

He remembered what the Jesus figure had said. “Go south? Toward the radio waves?”

She nodded. “New Zealand or Australia.”

“Australia,” Martha said, sitting up on the couch, groggy. “Watch out for large animals.”

“Always good advice,” La said. To Matt: “I’ll go slowly. You don’t have to strap in, but you’d better sit down. I’d suggest the couch.”

He sat next to Martha and put his arm around her. She leaned into him, and they eased back as the ship rose gently.

“This will be a couple of hours,” La said, “staying in the atmosphere. Might as well try to rest.”

Sleep after that? Matt thought. But Martha was already nodding off, from nightmare to dream. He closed his eyes and enjoyed her closeness, resting without sleep.

“Wake up,” La said. “We’re under someone else’scontrol. Better strap in.”

They scrambled into the acceleration couches, staring out at a wonderland. A city that looked like a huge ice sculpture, an abstraction of sweeping curves and gossamer threads glowing amber in the light of the setting sun. There were no other aircraft visible. A large harbor had quiet enough water to mirror perfectly the fantastic skyline.

“We’re being hauled in by some kind of tractor beam. I can’t understand what’s coming in on the radio.”

“You wouldn’t expect to, would you? After so long?”

“You could hope. But I’m just broadcasting a few phrases over and over in fifteen languages. See what they—”

“Hello, there,” the speakers said. The husky voice could have been either male or female; it had a slight Australian twang. “Please don’t be upset that we have taken control of your vehicle. All traffic near the city is regulated by the city.”

“I used to do that myself,” La said.

“From how far in the past did you come?”

“Twenty-four thousand years,” La said. “Do you get many time travelers?”

“Not really. The last one was several centuries ago. Does your machine involve an inexplicable anomaly having to do with gravitons, lots of them, in another dimension? ”

“It does, in fact. Can you help us explain it?”

“We can’t, actually. We don’t currently have working time machines.”

“Damn,” Matt said. “Another jump.”

“Maybe not,” La said. “We may hold the key for them to produce one.”

There was a flat area ahead, blinking yellow. They settled into it, in front of rows of streamlined vehicles of various shapes and sizes.

The ramp eased down and let in cold air. Their suits warmed as they walked down it.

Just before La stepped off, someone appeared. Nude, with small female breasts and small male genitals. “You still have gender,” it, or she, or he, said. “Except for you. You’re like me.”

“In some ways, I suppose,” La said. “You’re a projection? ”

“Yes. No one alive speaks anything like your language. People, physical people, are also cautious about coming into contact with you. There has been no disease in about twenty thousand years, except for an outbreak of influenza brought by a time traveler.”

“From the past, or the future?” Matt asked.

“Always from the past. If people have come from the future, they’ve kept it secret.” He looked closely at Matt. “You’re not from the future?”

“No, I’m from the 2050s.”

“As I told you,” La said, with a trace of asperity.

“Well, you looklike you could be from the future. Dressed like that. And the way your ship is armed.”

“It helps,” Matt said, “when you run into huge flying reptiles with teeth.”

“Oh . . . you were up there, what you’d call Indonesia. That was not a great success.”

“Bioengineering?” La said.

“In a way. Sort of an amusement park, which turned out too dangerous to be really amusing.

“We’ve been more successful, working with species that already exist. In Africa, we have elephants and apes and such with augmented intelligence; they’re delightful. Starting from scratch, as we did with the dinosaurs and Martians . . . you’d think they’d be easierto control, but they aren’t; they tend to go their own way.”

“You’ve made Martians on Earth?” Matt said.

He squinted, an unreadable expression. “Why would you want to do that? On Mars, of course. Big puffballs that bounce around and keep to themselves. They stopped talking to us centuries ago, millennia. And their language now, if it is still a language, is incomprehensible.”

After an uncomfortable silence, La said, “Can you take us to someone in authority?”

“No. You can’t come into the city’s biosphere. And no one’s coming out here. Some were in favor of destroying you, to make sure you couldn’t infect us. But more wanted to investigate you.”

“That’s good. Shall we begin the investigation?”

“It’s over. You may go.” He tilted his head, as if listening to something. “I think you’d better go, now. Where did you come from, in the past?”

“Los Angeles.”

“Go there. You’ll find it amusing.”

“Will the people there be expecting us?”

“There are no people there. Nowhere but down here. Go now.” He disappeared.

“We should take him at his word,” La said. “I suspect we’re in more danger here than we were from the dinosaurs. ”