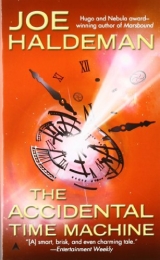

Текст книги "The Accidental Time Machine"

Автор книги: Joe William Haldeman

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

THE ACCIDENTAL TIME MACHINE

by Joe Haldeman

For Susan Allison:

about time.

1

The story would have been a lot different if Matt’ssupervisor had been watching him when the machine first went away.

The older man was hunched over his oscilloscope screen, staring into the green pool of light like a tweedy and corpulent bird of prey, fiddling with two knobs, intent on a throbbing bright oval that wiggled around, eluding his control. Matt Fuller could have been in another room, another state.

Sleet rattled on dark windows. Matt put down his screwdriver and pushed the RESET button on the new calibrator, a shoe-box-sized machine.

The machine disappeared.

He stared for about one second. When he was able to close his mouth and open it again, he said, “Dr. Marsh! Look!”

Dr. Marsh pulled all of himself reluctantly from the round screen. “What is it, Matthew?”

The machine had reappeared. “Uh . . . the calibrator. For a moment there, it . . . well, it looked like it went away.”

Dr. Marsh nodded slowly. “It went away.”

“I mean like it disappeared! Gone! Zap!”

“It appears to be here now.”

“Well, yeah, obviously. I mean, it came back!”

The big man leaned back against the worktable, tired springs on his chair groaning in protest. “We’ve both been up a long time. How long for you?”

“Well, a lot, but—”

“How long?”

“Maybe thirty hours.” He looked at his watch. “Maybe a little more.”

“You’re seeing things, Matthew. Go home.”

He made helpless motions with his hands. “But it—”

“Go home.” His supervisor turned off the ’scope and heaved himself up. “Like me.” He took his thermal jacket, a bright red tent, off the hook and shrugged it on. He paused at the door. “I mean it. Get some sleep. Something to eat besides Twinkies.”

“Yeah, sure.” Look who’s giving dietary advice. Maybe it was the sugar, though, and the coffee, and the little bit of speed after dinner. Cold french fries and a chocolate-chip cookie and amphetamines—that might make you see things. Or not see them, for a moment.

He waved good night to the professor and sat back down at the calibrator. It was prettier than it had to be, but Matt was funny that way. He’d found a nice rectangle of oak in the “Miscellaneous” storage bin, and cut out the metal parts so they fit flush on top of it. The combination of wood with matte black metal and glowing digital readouts pleased him.

He always looked kind of scruffy himself, but his machines were another matter. His bicycle was silent as grease and you could play the spokes like a harp. His own oscilloscope, which he had taken apart and rebuilt, had a sharper display than the professor’s, and no hiss. Back when he’d had a car, a Mazda Ibuki, it was always spotless and humming. No need for a car at MIT, though, and plenty of need for money, so somebody back in Akron was despoiling his handiwork on the Mazda. He missed the relaxation of fiddling with it.

He ran his hand along the cool metal top of the machine, slightly warm above the battery case. Ought to turn it off. He pushed the RESET button.

The machine disappeared again.

“Holy shit!” He bolted for the door. “Professor Marsh!”

He was at the end of the hall, tying on his hat. “What is it this time?”

Matt looked over his shoulder and saw the calibrator materialize again. It shimmered for a split second and then was solid. “Uh . . . well . . . I don’t guess it’s really important. ”

“Come on, Matt. What is it?”

He looked over his shoulder again. “Well, I wondered if I could take the calibrator home with me.”

“What on Earth would you calibrate?” He smiled. “You have a little graviton generator at home?”

“Just some circuit-board tests. I can do them at home as well as here.” Thinking fast. “Maybe sleep in tomorrow, not come in through the snow.”

“Good idea. I may not come in either.” He finished putting on his mittens. “You can e-mail me if anything comes up.” He pushed open the door against a strong wind and looked back, sardonic. “Especially if the thing disappears again. We do need it next week.”

Matt went back and sat down by the calibrator and sipped cold coffee. He checked his watch and pushed the button. The machine shimmered and disappeared, but only the metal box; the oak base remained, a conical woodscrew hole in each corner. It had done that the last time, too.

What would happen if he put his hand in the space where the box had been? When it came back it might chop him off at the wrist. Or there might be a huge nuclear explosion, the old science fiction version of what happens when two objects try to occupy the same space at the same time.

No, there were plenty of air molecules there when it came back before, and no obvious nuclear explosions.

It shimmered back, and he checked his watch. A little less than three minutes. The first disappearance had been about one second, then maybe ten, twelve seconds.

His watch was a twenty-dollar dime-store Seiko, but he was pretty sure it had a stopwatch function. He took it off and pushed buttons at random until it behaved like a stopwatch. He pushed the button on the watch and the RESET button simultaneously.

It seemed to take forever. The rattle of sleet quieted to a soft whisper of snow. The machine reappeared and he clicked the stopwatch button: 34 minutes, 33.22 seconds. Call it 1, 10, 170, 2073 seconds. He crossed over to the professor’s desk and rummaged around for some semilog graph paper. If you took an average, it looked like the thing went missing about twelve times longer each time he pushed the button.

Do the next one, about six hours, at home. He found a couple of plastic trash-can liners to protect the machine, but before he wrapped it up he put a cardboard sleeve around the RESET button and fixed it in place with duct tape. He didn’t want the machine disappearing on the subway.

It was one unholy bitch of a night. The sleet indeed had turned to snow, but there were still deep puddles of icy slush that you couldn’t avoid, and Matt hadn’t worn boots. By the time he got on the Red Line, his running shoes were soaked and his feet were numb. When he got off at East Lexington, they had thawed enough to start hurting, and the normal ten-minute uphill walk took twenty, the sidewalks slippery with ice forming. Wouldn’t do to drop the calibrator. He could build a new one in a couple of days, if he could find the parts. Or his successor could, after he was fired.

(All the calibrator was supposed to do was supply one reference photon per unit of time, the unit of time being the tiny supposed “chronon”: the length of time it takes light to travel the radius of an electron. Nothing to do with disappearing.)

He managed to take off a glove without dropping the machine, and his thumbprint let him into the apartment building. He trudged up to the second floor and thumbed his way into his flat.

Kara had only been gone for a couple of days, and most of that time he’d been in the lab, but the place was already taking on bachelor-pad aspects. The stack of journals and printouts on the coffee table had spilled onto the floor, and though he had sorted through it twice, looking for things, it hadn’t occurred to him to stack it back up. Kara would have done that the first time she walked through the living room. So maybe they weren’t exactly made for each other. Still. He put the calibrator on the couch and stacked the magazines. Half of them slid back onto the floor.

He went into the kitchen and didn’t look in the sink. He got a beer from the refrigerator and took it into the bathroom along with the new Physical Review Letters. He ripped off his shoes and ran a few inches of hot water into the tub and blissfully put his feet in to thaw.

There was nothing in Lettersthat particularly interested him, but reading it let him pretend to be doing something useful while he was mainly concerned with thawing out and drinking beer. Of course that made the phone ring. There was an old-fashioned voice-only in the bathroom; he leaned over and punched it. “Here.”

“Matty?” Only one person called him that. “Why can’t I see you?”

“No picture, Mother. I’m on the bathroom phone.”

“I’m sending you money so you can have a phone in the bathroom? I wouldn’t mind a phone in the bathroom.”

“It was already here. It would cost extra to take it out.”

“Well, use your cell. I want to see you.”

“No, you don’t. I look like I’ve been up for thirty-six hours. Because I have.”

“What? You’re killing yourself, you know that. Why on Earth would you stay up that long?”

“Lab work.” Actually, he was disinclined to come home to the empty apartment, the empty bed. But he’d never told his mother about Kara. “I’m going to sleep in tomorrow, maybe not even go to the lab.” He kept talking and pushed the HOLD button down for a moment. “Call coming in, Mother. Buzz you tomorrow on the cell.” He hung up and raised the beer to his lips, and there was a perfunctory knock on the apartment door. It creaked open.

He wiped his feet inadequately on the bathroom throw rug and stumbled into the living room. Kara, of course; no one else’s thumb would open the door.

She was pretty bedraggled, pretty andbedraggled, and had a look that Matt had never seen before. Not a friendly look.

“Kara, it’s so good—”

“I finally stopped trying to call you and came over. Where have you beensince yesterday morning?”

“At the lab.”

“Oh, sure. You spent the night at the lab. Forgot to route to your cell. With the secret number even I can’t call.”

“I did! I mean I didn’t.” He spread his arms wide. “I mean I spent the night at the lab and they don’t allow you to route calls there.”

“Look, I don’t care where you spent the night. Really, I don’t care at all. I just need something from the bathroom. Do you mind?”

He stepped aside and she stomped by him, dripping. He followed, also dripping.

She looked in the medicine cabinet and slammed it shut. Then she looked at the tub. “You’re taking a bath in two inches of water?”

“Just, uh, just my feet.”

“Oh, of course, of course, your feet.” She jerked open a drawer. “You’re weird, Matt. Clean feet, though. Here.” She pulled out a baby blue box of Safeluv contraceptive discs. “Don’t ask.” She pointed a finger into his face. “Don’t you dare ask.” Her face was flushed and her eyes were bright with held-back tears.

“I wouldn’t—” She pushed her way past him. “Won’t you just stay for a cup of coffee? It’s so bad out.”

“Someone’s waiting.” She stopped at the door. “You can take my thumb off the door now.” She paused, as if wanting to say something more, and then spun into the hall. The door closed with a quiet click.

2

Matt did know something about time travel,though it wasn’t his specialty. He didn’t really have a specialty, not anymore, though he was only a couple of hard courses and a dissertation away from his doctorate in physics.

Everybody does travel through time toward the future, trivially, one second at a time. There was no paradox involved in going forward even faster—in fact, modern physics had allowed that possibility since Einstein’s day.

Demonstrating that, though—time dilation through relativistic contraction—requires either really high speeds or the ability to measure very small amounts of time. You have the “twin paradox,” where one twin stays at home and the other flies off to Alpha Centauri and back at close to the speed of light. That’s eight light-years, so the traveling twin is about eight years younger when he returns—to him, his stay-at-home brother has traveled forward in time eight years.

They don’t build spaceships that fast, but you can do it on a smaller scale with a pair of accurate clocks. Send one around the world on a jet plane, and when it comes back, the traveling clock will be about a millionth of a second slower than the stay-at-home.

Matt had been familiar with that stuff since before puberty, and then after puberty, the pursuit of physics had exposed him to more sophisticated time-travel models, Gцdel and Tipler and Weyland. But they all required huge deformations of the universe, harnessing black holes and the like.

Not just pushing a button.

Matt woke up on the couch, groggy and aching. Past the row of empty beer cans on the coffee table, an old movie capered on the TV screen. It had been Fellini when he fell asleep. Now it was Lucille Ball with a grating laugh track. He found the remote on the floor and sent her back to the twentieth century.

His feet were cold. He shuffled into the bathroom and stood for a long time under a hot shower.

He still had several days’ worth of clean clothes hanging in the closet, relics of when there used to be a woman living here. Was Kara fanatically folding and hanging for another man now?

The coffee was ready by the time he got dressed. He sweetened a cup with a lot of honey and made a space at the kitchen table by pushing aside some three-day-old newspapers. He brought his bag to the table and took out the machine, still wrapped in the trash-can liner, his notebook, and the piece of graph paper from the professor’s desk.

He plugged in the notebook and scanned the graph paper into it, with the four data points. The first two were guesses, the third approximate, and the fourth timed with a stopwatch. He drew in appropriate error bars with a stylus and asked the notebook to do a Fourier transform on them. As he expected, it gave him a set of low-probability solutions that curved all over the map, but the cleanest one was a straight line with a slope of 11.8—so the next time he pushed the button, the thing should be gone for 24,461 seconds. Six hours and forty-eight minutes, give or take whatever.

Okay, this one would be scientific. He got the digital alarm from his bedroom and set it to show seconds. He put a fresh eight-hour tab into his cell and set it for continuous video, then propped it up on a stack of books so that it stared at the clock and the machine. As an afterthought, he cleared the junk away from the table behind it, and restarted the cell. This would be part of the history of physics. It ought to look neat.

He rummaged through the everything drawer in the kitchen and found his undergraduate multimeter. The calibrator machine’s power source was a Madhya deep-discharge twenty-volt fuel cell, and the multimeter said it was 99.9999 percent charged. He showed the result to the camera. See how much power the thing drew while it was gone.

It was 9:58, so he decided to wait until exactly 10:00 to push the button. Out of curiosity, he pulled a two-dollar coin out of his pocket and set it on top of the machine. That would be his dramatic sound track: the clink of the coin falling when he pushed the button.

His eye on the clock, he could feel his heart racing. What if nothing happened? Well, nobody else would see the tab.

A split second before ten, he jammed his thumb down on the button. The machine dutifully disappeared.

It took the two-dollar coin with it. No clink.

That was interesting. Both he and the coin had been in contact with the machine, but the coin had been on the metal box, not the nonconducting plastic button. What would have happened if it had been him touching the metal instead?

He should have put the cell onthe machine, rather than outside. Get a record of what happens to it when it’s not here. Not here and now.

Well, next time.

Of course the phone rang. He peered at the caller ID. His mother. When it stopped ringing, he called her from the bathroom.

“You’re calling from the bathroom again,” she said.

“Something wrong with the cell.” Let’s not tell Mother about the disappearing machine. “Why did you call me?”

“What, you were sleeping?”

“No, I’m up and around. Why’d you call?”

“The storm, silly. Are you doing all right with the storm?”

“Sure.”

“What do you mean, ‘sure’? You got power and water?”

“Yeah, sure.” He went to the little window at the end of the room and pulled the blinds. It was solid gray, snow packed so thick that no light came through.

“Well, we don’t. The power went out right after I got up. Now they’re telling people to boil the water before you drink it.”

He just stared at the window. Snow ten feet deep?

“Matthew? Hello?”

“Just a minute, Mom.” He set the phone down on the rim of the tub and stepped to the front room. He peered through the blinds.

There was snow, all right, but only a couple of feet. The wind was fierce, though, rattling the windowpanes. That was it. The bathroom window looked out over a temporarily vacant lot. Wind blowing from the north had an unobstructed path more than a hundred yards long. So the snow had packed up against the north wall, including the bathroom window.

He picked up the phone. “So what’s the matter there?” his mother said.

“Just checking. It’s not so bad here. Anything I can do?”

“If you had a car.”

“Well.” It had been a graduation gift, and he’d sold it when he moved back to Boston.

“You couldn’t rent one.”

“No. I wouldn’t in this weather, anyhow, Boston drivers. You need something?”

“Candles, milk. A little wine wouldn’t hurt.” She lived in a dry suburb, Arlington. “Some bottled water—how’m I going to boil it? Without the electric?”

“Let me check on the T. If it’s running, I could bring you out some stuff.”

“I don’t want you should—”

“Make a list and I’ll call you back in a couple minutes.” He hung up and calculated. If his extrapolation was right, the machine would reappear just before five. Plenty of time, even with the weather.

He should eat something first. Nothing in the fridge but beer and a desiccated piece of cheddar cheese. He popped his last can of Boston Baked Beans—made in Ohio—and nuked them while he chased down a piece of paper and a pen for a list.

Candles, wine, milk, water. He called and she added bread, peanut butter, and jelly. Red currant if they had it. Some sardines and Dijon mustard—don’t worry, she’d pay. Fish? She’d better.

He poured the beans over a slice of bread that was dry but not moldy and squelched some ketchup over them. He opened another beer and watched the Weather Channel while he ate. The snow should stop by noon. But more tomorrow. A good time to take a long weekend.

He tried not to think about being bundled up with Kara while the snow drifted down. Hot chocolate, giggles. Some giddy exploration of the outer limits of love. Perhaps.

The beans had turned cold. He finished them and dressed in layers and went out to slay the wily groceries.

The combat boots he’d bought in Akron were clumsy but dry, good traction, trudging downhill. The wind had gentled somewhat, and he almost enjoyed the walk. Or maybe he enjoyed not being in the apartment alone.

No candles at the grocery store except little votive ones. He bought her a box of two dozen and a five-liter box of cheap California wine. Get one for himself on the way back. Two jugs of water. Everything but the water went into his backpack. He lumbered off toward the Red Line.

His mother was just two stops down, but more than a mile walk after that. By the time he got there, he was regretting the second gallon of water. Mom could brush her teeth with wine.

She was glad to see him in spite of the fact that he didn’t get any matches to go with the candles. He searched and found some in his father’s old workshop, where Matthew knew he’d sometimes escaped to smoke dope. They sat in the kitchen and had a glass of wine and some chocolate, and he said he had to get back to work, which was true, even though the work was not of an arduous nature.

On the way back he picked up the wine and a couple of days’ groceries, and a cheap camera phone in a blister pack. He could have gone on into Harvard Square to Radio Shack for a little button camera, since he didn’t need a new cell, but it probably would have cost at least as much. And he didn’t want to miss the reappearance.

The wind and snow had started up again when he got off the subway to make his way home. He was shivering by the time he got inside. A glance verified that the machine was still off to wherever it was, so he went straight into the kitchen and started water for coffee and to warm his hands.

A little more than an hour to go, as he sat down on the couch with his coffee. He picked up his notebook and clicked on the calculator, and made a short list:

1. (1.26 sec) (extrapolating back)

2. (15)

3. (176)

4. 2073 s.

5. 24,461= 6h 48m

6. 3.34 days

7. 39.54 d.

8. 465 d.

9. 5493 d.= 15 y.

So he had to plan. The next time he pushed the button– if the simple linear relationship held true—the thing would be gone for over three days. Next time, over a month; then over a year. Then fifteen years, and way into the future after that.

So it was a time machine, if kind of a useless one. Unless you could find a way to reverse it—go up fifteen years and come back with the day’s stock quotations. Or a list of who had won the World Series every year in between. But simply putting yourself in the future, well, you could do that by just standing around. No profit in it unless you could come back.

He calculated two more numbers, 177.5 years and 2094. If you went that far up, if would be like visiting another planet. But you couldn’t come back, like the guy in the Wells novel, and warn everybody about the Morlocks. And it might get lonely up there, with nobody but Morlocks to grunt with.

Maybe it would be a high-tech future, though, and they’d know how to reverse the process.

No. If they could do that, we would have seen them around. Playing the stock market, betting on horses.

But they wouldn’t necessarily look any different from us. Maybe they came back all the time—made a few bucks and then went back to the future. Of course you had the Ray Bradbury Effect. Even a tiny change here could profoundly affect the future. Don’t step on a butterfly.

Through all this rumination, he kept staring at the spot. Four forty-eight came, and nothing happened. He started to panic, but then it shimmered into existence, just before 4:49. Have to adjust the equation slightly.

The two-dollar coin was where he had set it. He should have put a watch next to it. A cage with a guinea pig. And the camera.

He checked the Madhya fuel cell, and it was at 99.9998 percent, a drop of a hundredth of one percent. It might have lost that by capacitance, though; the circuit open. See what the next data point shows.

Three days and eight hours, next time. He counted on his fingers. Just after midnight Monday. He could call in sick that day. Marsh wouldn’t miss him.

He would miss the machine, though. Could he build a duplicate by Tuesday? Nothing to it, if he had all the components in front of him and a properly equipped worktable. But it would be hard to gather all that stuff over a weekend when the Institute and the city were mostly shut down. You couldn’t go to a pharmacy and pick up a gram of gallium arsenide, anyhow.

Even with the ’tute open, there would be a lot of paperwork. Of course if you were just borrowingthings . . .

Matt had been a student at MIT for five years, and an employee for three more. He went back to the everything drawer and pulled out a large ring with a couple of dozen keys identified with little paper labels.

One of them would open nine out of ten MIT doors, but those were mostly uninteresting classrooms and labs. The others were special offices and storerooms.

Most students who had been around a long time had access to a similar collection, or at least knew someone like Matt. MIT had a venerable tradition of harmless breaking and entering. When he was a second-semester freshman, Matt had been taken on a midnight tour of the soft underbelly of MIT, crawling through semisecret passageways that crackled with ozone and dripped oily condensate, emerging to tiptoe through experiments in progress—look but don’t touch—room after room of million-dollar gadgetry protected only by the hackers’ code of honor. You don’t mess with somebody else’s work.

And you don’t steal. But then it wouldn’t be stealing if it was for an Institute project, would it?

He brought up a schematic on the computer and made a list of components he wouldn’t be able to just pick up in his own lab, or rather Professor Marsh’s. He knew where all of them would be, since he’d already built the thing once.

Saturday night in a blinding snowstorm. If he met anybody else, they’d be hackers on similar errands. Or janitors or security guards, neither of whom would be much of a problem. He’d guided freshmen on the tour dozens of times, and they only had to run like hell twice.

He half filled a thermos with the rest of the coffee and made two peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, and put them in his knapsack along with the computer and key ring. He emptied out a multivitamin jar and sorted through the various pills. He broke a large Ritalin in two and swallowed one half. The other he folded up into a scrap of paper and put in his shirt pocket. This would be an all-nighter.

What he really wanted to do was set up the machine with the camera and a watch, and send it off into the future. But not until he had a duplicate.

He had to smile when he imagined the look on Professor Marsh’s face when he pushed the RESET button on the duplicate. He tried to hold on to that thought as he barged out into the blowing cold.

3

It turned out to be more than an all-nighter. Hehad to sneak into fourteen different labs and storerooms before he had all the parts in his bag. In some places, he left IOU notes; in some, he assumed people wouldn’t miss the odd resistor or thermocouple.

A thin gray winter dawn was threading through the window when he gathered all the parts together at his bench. He hadn’t been able to quite match everything precisely– all the electronic and optical components had the right characteristics, but they weren’t all from the same manufacturers as before, which shouldn’t make any difference. But then the machine shouldn’t disappear, either.

He had a pine plank instead of the furniture-quality oak he’d scrounged. Surely that wouldn’t make any difference, the neutral platform. He trimmed it with a table saw to just the right dimensions, then he found the cardboard template he’d used as a guide and drilled holes in the board to position the various components. Then he took it to the chemical hood and spray painted it with two coats of glossy black enamel. It was fast-drying, supposedly, but he set a timer for a half hour and stretched out on the bench for a nap, his more or less dry boots folded for a pillow.

Waking up not too refreshed, he took the rest of the Ritalin and heated up half a 1000-ml. beaker of water for coffee. While it was coming to a boil, he set out all of the components in order next to the drilled and painted plank and then got together the tools and materials he’d need to put it all together.

This last step was the most satisfying, but also one prone to spectacularly stupid error, because of familiarity and fatigue. He got a big mug of coffee and stared at the neat array as the drug came on slowly, waking him up. He assembled the calibrator mentally, writing down the steps in sequence on a yellow pad. He studied the list for a few minutes, then rolled his sleeves up neatly and got to work.

It was a mind-set he remembered from childhood, spending hours in the meticulous construction of airplane and spaceship models, excitement holding fatigue at bay. Now, as then, after he’d soldered the last join and firmly tightened the last tiny screw, he felt a little letdown, the fatigue hovering.

He slid the fuel cell into place and tightened the contacts. Push the RESET button or not?

Had to try it. He set his watch to the stopwatch function and pressed both buttons simultaneously.

Nothing happened. Or, rather, the calibrator emitted one photon per chronon, as designed. Dr. Marsh could have this one.

A heavy lassitude flowed into him. He stretched out on the lab bench again. The thought of his soft bed at home was seductive, but the subway wouldn’t start till seven, Sunday. He checked his watch, but it was still set on stopwatch, earnestly adding up the seconds. He left it that way. Three hours and seven seconds later, he unfolded, groaning, and sat up. It was after nine, good.

He left the calibrator on the shelf and went out to face the Cambridge winter. It was overcast and bitter, in the teens or single digits. No new snow, but plenty of old. He could hear a snowblower somewhere on campus, but it obviously hadn’t made it to the Green Building. He crashed through the snow, more than knee-deep, toward the Red Line. The smell of Sunday morning coffee at Starbucks lured him in.

He put enough sugar and cream in the coffee to call it breakfast, and thought about the next stage of the experiment. The machine would be away for three days and eight hours. There would be the cell camera recording the machine’s surroundings, and he’d leave his watch in there to record the passage of time—or buy an even cheaper one that he wouldn’t mind losing.

A guinea pig. See whether something alive would be affected by the suspension of time, or whatever was going on.

An actual lab animal would be pretty complicated: cage and water and all. He thought about catching a cockroach, but actually he hadn’t seen any of them since Kara made him bring the bug man in.

Something that would survive for three days without maintenance. Something he could buy cheap or borrow . . .

A turtle. When he’d gone to the Burlington Mall with Kara to get new pillows, she’d dragged him into the pet store. They had a terrarium full of the little rascals.

They wouldn’t be open on Sunday, though. He toyed with the idea of breaking in, risking months in jail for a two-dollar turtle. No. It wasn’t MIT. The security guards would take one look at him, a shaggy drug-addled young male dressed like a street person, and shoot to kill.

The Starbucks had a phone book, though, a much-abused sheaf of dirty yellow paper, and he found the number and punched it up on his cell.

“Go to hell,” a woman’s voice said. He checked the number and no, he hadn’t called Kara by mistake. “Pardon me?”

“Oh! I’m sorry!” She laughed. “I thought you were my boyfriend. Who else would call on a Sunday morning?”