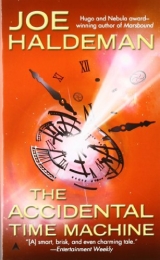

Текст книги "The Accidental Time Machine"

Автор книги: Joe William Haldeman

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

The ship rose like a fast elevator, the ground dropping away, roofs shrinking. Martha clutched for Matt and buried her face in his chest.

Arms full of soft girl for the first time in a long time, Matt patted her back reassuringly. “It’s all right. It’s very ordinary.” But please don’t let go just yet.

“I know, Professor,” she said, her voice muffled. “I’ve seen pictures. But it’s so fast.”

La smiled knowingly at Matt. “She’ll be all right. I’ll keep it slow.”

“How fast can it go?”

“Mach 6 to 8, depending on the load and the altitude. But we’re not going far; I’ll keep it subsonic.”

The suburbs rolled on and on toward the horizon, then stopped. “Mountains,” Matt said with a little awe. He’d only been west a couple of times in his life. “Look, Martha.”

She carefully lifted her head and whispered, “God,” not in blasphemy.

“No buildings,” Matt said.

“All these mountains are protected. About half of the area west of the Mississippi has been more or less artfully ignored, and has gone back to its natural state. A few people live in the protected areas, antisocial or sick of the modern world. But the law says they have to live in a primitive way, and they usually tire of it soon.”

“You said those two, Arl and Em, were typical? That level of prosperity?” Not to say excess.

“They’re actually below average, the forty-second percentile in terms of total holdings. They’re not very good at horse-trading, as you would say.”

“Horses?” Matt had never heard the term.

“Bartering. They have a little less than the basic dole that people get at birth.”

“You know that much about everyone?” Martha said, not taking her eyes off the mountains rolling under them.

“Much more than that,” La said, “but that’s all I am, Martha—memories, perceptions, thought processes. I’m what’s evolved from a human committee and a machine that was constructed to keep this huge city running.”

“A city of millionaires,” Matt said.

She nodded placidly. “It’s been that way for centuries. Ever since we started getting free power from the sea, room-temperature fusion. Automated synthesis of consumables, distributed to a stable population of 100 million. Everybody rich and happy.” She smiled. “Also complacent and rather stupid, you may have noticed.”

“Arl said that people don’t do science anymore. It’s too complicated, and has to be done by machines.”

“What, are you worried about unemployment? There aren’t any jobs, as such, for anybody. Certainly none for physics professors two millenniums out of date.”

“But you do have universities. She had a doctorate, they said.”

“The universities are like social clubs, I’m afraid. They give each other pieces of paper; it keeps them happy. Out of trouble.”

“No wonder people take to the hills.”

“You’d be surprised how few.”

“But there must be people doing the Lord’s work,” Martha said. “That takes education.”

“That depends on whom you’re preaching to.” La shook her head, perhaps in sympathy. “There’s not much organized religion. Not much religion at all.”

“The world has been that way before.”

La looked over her shoulder, in the direction of travel. “Getting close to home now.”

“We can’t have gone four hundred kilometers,” Matt said.

“Oh, I don’t live in the city proper. I hope you do like mountains.”

Matt leaned to his left and could see that they were approaching the “palace,” a delicate Disney fantasy of a place, resting on a pinnacle that couldn’t have been natural.

“But you’re not really ‘here’ the way we are. You don’t live in a physical place. Arl seemed to think you could be everywhere at once, at least at tax time.”

“Complaining again. Yes, I spread myself pretty thin that time of the year.

“But I do always have a locus. I can generate 100 million images that can all do something simple, like arguing over taxes. There’s still a ‘me,’ though, usually here in the palace.”

The craft had been losing speed with a low rushing sound. It hovered over a lawn and descended. “This is where my physical memory is located—so I do feel more comfortable here. Even a hundred or so kilometers away, I can feel the femtosecond lag in response time.”

“We must seem pretty slow to you,” Martha said, which slightly surprised Matt. But she wasn’t dumb.

“Not really. I had flesh once. I have a feeling for the human passage of time.” She turned to Matt. “And the inhuman. Let me get you settled into your apartment, and then we can talk about that machine in your bag. The one you stole from poor Professor Marsh.”

An apparently human valet led them to a two-bedroom apartment, simplifying Matt’s existence while dampening his hopes.

The apartment was conservative twenty-first century, lots of wood and cloth and stucco. Lamps instead of glowing walls. Doors that apparently didn’t morph open. Matt had to show her how the toilet worked; it was the paperless kind, using jets of water and air. The first time she used it, she squealed and giggled in a satisfying way.

They both had large closets full of clothes. Martha sorted through hers and picked out slacks and a long-sleeved shirt.

“This is pretty,” she said, stepping out of the outfit Em had chosen, “but it’s too, you know, revealing. She wriggled into the shirt, otherwise nude, and noticed Matt’s expression. “This doesn’t bother you, Professor?”

“Oh no, no. I’m getting used to it.”

“What do you mean?”

“We’re just not so casual about, uh, being naked where I come from.”

“Dressing? That’s silly.”

“I agree. I totally agree.”

“Well, you ought to change, too. You don’t mind my saying so?”

“No, no, that’s . . . fine.” It did pose a tactical problem, which showed no immediate sign of going away. He solved the problem by grabbing clothes at random and changing with his back to her. She probably didn’t see anything, but then she probably wasn’t looking.

The valet had shown them where to go when they were ready, a parlor room at the end of their corridor.

It looked old and French, delicate ornate furniture, ancient oil paintings on fabric-covered walls. La was softly playing on a harpsichord when they walked in.

“Welcome.” She stood up and gestured to where three chairs were arranged around a glass-topped table with a tea service and a plate of cookies and petits fours.

Matt moved the teapot to one side and lifted out the machine. “I take it that even now, you don’t have one of these.” La sat down staring at it, and shook her head. “And you don’t know how it works?”

“How? No,” she said. “It’s been clear for more than a thousand years whyyour machine works. But knowing why isn’t the same as knowing how. Knowing that E= mc 2 doesn’t mean you can take some kitchen appliance and turn it into a nuclear weapon.”

“So why does it work?”

“The part that’s broken is the graviton generator. But it’s not broken in four-dimensional space-time. That’s why they could build a thousand copies of the machine and never duplicate its effect.

“In ‘our’ space-time, as we affectionately call it, the calibrator works perfectly. One puny graviton per photon. But in some dimension five or higher, it spews out a torrent of gravitons.” She leaned back and stared up at the ceiling. “How can I put this in a way you can understand?”

Matt was growing excited. “I think I know what you’re getting at!”

She nodded. “In your primitive terms—they still used string theory?”

“Go on, yes?”

“In that way of thinking, our space-time continuum is a four-dimensional brane floating through a larger ten– or eleven-dimensional universe—”

“Wait,” Martha pleaded, “I don’t understand. A floating brain?”

Matt spelled the word. “It’s short for ‘membrane.’ ”

“They couldn’t just say membrane?”

“ ‘Membrane’ means something else. A brane is like . . . it’s like a reality. Like we live in one four-dimensional reality, but there could be countless others.”

“But where would you put them? Where could they be?”

“They’re inside a larger brane. Five or six or more dimensions. ”

“What would thatlook like?”

He shrugged. “We don’t know. We can only perceive four dimensions.” She nodded slowly, lips pursed.

“All right,” La said. “As Matt said, there are countless other four-dimensional branes, but what’s important are the five-dimensional ones that can be made to envelop ours. Your broken graviton generator attracted one of these beasts and apparently made a permanent connection. Permanent from our point of view. Instantaneous, hardly noticeable, in five dimensions.”

“But in ours,” Matt said, “it makes a closed timelike curve?”

“In a way. But that would only make a time machine that went backward in time. Yours moves forward, faster and faster. Something in that five-dimensional brane is connected to a huge singularity in our brane: the heat death of the universe. The end of time.”

“The End Times,” Martha whispered.

“It’s more than ten to the thousandth power years in the future. The stars die, the black holes evaporate, and finally everything stops moving.”

“I want to go find out whether I can die.” La’s smile was almost a leer. “I think we can help each other.”

16

After tea, they took the machine downstairs, to aroom that functioned as a kind of laboratory. It was austere, evenly lit from glowing walls and ceiling, with a series of identical tables numbered one through ten. Matt, following orders, set the machine on each table for a minute or two while La stared at it without expression. Then she would nod and drift on to the next one.

At the end, she nodded, and then shook her head. “I have to share this with some others. Why don’t you two get some rest?

“You can go anywhere in the place. If you’re lost or want something, just ask for help. Out loud.” She disappeared.

Matt put the machine back into the bag and wouldn’t let Martha carry it. “Look. I’m not a professor here, and you’re not a graduate assistant. We’re just time travelers, both of us unimaginably far from home.”

“But . . .”

“You know the term ‘stranger in a strange land’?”

She nodded. “Exodus 2:22. That’s how Moses described himself.”

“And that’s what we are; that’s the largest thing we have in common. Though the ‘lands’ we came from are also strange to one another, still, this is the one we’re stuck in. Together.”

“I don’t know. I have to think about that, Professor.”

He sighed. “Matthew, or Matt. Please? ‘Professor’ makes me feel old.”

“Only when I say it?”

“Oh . . . maybe. Matthew?”

“I’ll call you Matthew if you let me carry the bag.”

He handed it to her. “Let’s go find a view. It must be close to sunset.”

They walked down the corridor until it ran into a wall, and then followed the wall until it led to an outside door, which opened easily to a parapet that went out about a meter and a half into pure sky—no protective railing.

“It’s gorgeous,” Matt said. The mountains were crimson and orange in the setting sun, with purple shadows deepening to indigo. The shadow of the palace’s pinnacle was a narrow, straight slash.

He stepped out. “Professor! Don’t . . . Matt!” He held a hand out and it hit an invisible, marshmallow-soft wall.

“It’s safe. There’s a pressor field.” To demonstrate, he folded his arms and dropped back against it, which made her gasp.

She put her hands over her eyes. “Please don’t.”

“Okay.” He angled forward and held out a hand to her. “Let’s go find that sunset.” She did take his hand and followed him around the parapet, staying close to the wall.

The sunset was a brilliant wash of color, deep red merging into salmon and an improbable yellow with a breath of green, fading into blue. Inky blue overhead, with a few pale stars.

She stared wide-eyed, her lips slightly parted. Matt noted that her eyes were gray, and she was about as pretty a girl as he had ever stood this close to, even with the small scar. He was still holding her hand.

She let go and touched her sternum. “Sweet Jesus,” she breathed. “My heart is going so fast!”

“Mine, too,” Matt said, though it wasn’t all geology and altitude.

“Maybe . . . we should go in. This is wonderful. But I feel almost like I’m going to faint.”

“The air is a little thin,” he said, sidling around her and taking her hand again. “Go back the same way?”

“Please.” They picked their way around, Matt walking slowly and thinking furiously.

She’s not a young girl, he told himself, in spite of her lack of experience and information. She’s almost as old as Kara was when they broke up a couple of months or millenniums ago.

But you can’t talk yourself out of the truth that she isa child, when it comes to dealing with the opposite sex. Don’t press her; don’t take advantage. Be a man.

Unfortunately, “be a man” was also the counsel the rest of his body was giving.

What if they never did get back to their own times? As they moved on into the future, and people became more and more strange, they would be the only potential partners for one another on the planet.

Her hand was cold and damp. This is plenty of strangeness for the time being. Don’t be a scoundrel. She put her life between you and a crazy cop with a gun. Be a man. Be a man, for a change.

When they went through the door he let go of her hand.

“Thank you.” She leaned against the wall, panting.

“Are you okay?”

“I think so.” She looked up and down the corridor. “You know, she’s right. We should rest. Much as I’d like to explore, I ought to lie down for a little bit.” She pointed. “Is that the way back?”

A valet appeared. “Yes. On your left, second corridor, two doors down.” He faded away.

“I guess they’re always watching,” he said.

“She is. He’s part of her.” She looked around. “That gives me a strange feeling. Like I’m being spied on.”

“I suppose. But she’s been doing it for so long, she’s seen everything.”

“She hasn’t seen medo everything.” She started off down the corridor.

“Wait,” Matt said, and touched the bag’s strap. “Let me take that. You’re tired.”

“All right.” She surrendered it and smiled. “Professor.”

Back in the apartment, she stretched and yawned and relaxed onto the couch. He sat down and set the bag between them.

She looked inside. “Wish we still had that bottle of wine.”

“Yeah,” he said. “The sixty thousand bee shits aren’t doing us any good.” She giggled at that, and there was a knock on the door.

“Come in?” Matt said. The valet eased the door open and entered with a tray. Two bottles of wine, red and white, and two glasses. He set it on the end table next to Martha.

“You did that so fast,” she said.

“No, Martha; La anticipated your requirements. If you had asked for coffee or tea, I would be here with it.”

“I’d like a glass of iced watermelon juice,” Matt said.

“It would be synthetic,” the valet said, “but I can have it in two minutes. Unless you are joking.”

“I’m joking. Thank you.” The valet inclined his head and disappeared.

They both stared at the spot where he’d been. Then Martha pulled the stopper out of the white wine, studied it, and put it aside. “Red or white?”

“Take white,” he said. She poured a glass and passed it to him, then poured one for herself.

He held out his glass, but they evidently didn’t have that custom. She had a stranger one: she touched the surface of the wine with a fingertip and shook a drop off onto the floor.

She smiled at him. “My mother always did that. She said she promised hermother that she would never drink a drop of wine. That was the drop she never drank.”

Matt took a sip; it was icy cold but not too dry, flowery. “Did MIT let you go visit your mother?”

She nodded. “Easter and Christmas, when the roads allowed. But she’s failing, was failing.” Her mouth went into a hard line, and she bit her lower lip.

“Mine, too,” Matt said. “My mother. The last couple of times I saw her, she didn’t know who I was.”

She nodded without looking at him. “Matthew. A good name. But . . . you’re not Christian?”

“I was born a Jew.”

“Like in the Bible?” He nodded. “We don’t have them, you, not in a long time.”

He didn’t really want to know, but had to ask: “What happened to them? There used to be lots, in Boston and Cambridge.”

“They left, I guess. A lot of people left during the One Year War. Coming out this way.”

“People used to say the Jews ran Hollywood. I guess we could run toHollywood.”

She considered that, not getting the joke. “You miss it. Your church.”

“Synagogue, no. I stopped going when I was younger than you.”

“Your parents let you not go?”

“My mother had stopped years before. My father never went.”

“That’s so strange. I never knew anyone who didn’t go to church.” She sat up straight. “I guess I am one, now.”

“Until you get back. God must understand.”

She looked at him. “You don’t believe that.”

“No. I should have said, ‘If there is a God, I can’t imagine that he would not understand.’ ”

“Em and Arl, they didn’t act like believers. They acted as if Christians and Muslims were unusual.”

“Comes and goes, I suspect. There weren’t a lot of religious people in the time and place I left. And then I wound up in yours, where everybody believed. Maybe the pendulum will have moved back the next time we jump.”

“How far into the future will that be?”

“If our calculations were correct, twenty-four thousand more years.”

She took a sip of wine. “About four times the age of the Earth.”

“According to the Bible.”

She reached into the bag and took out the Bible. “May I take this? Try to read myself to sleep.”

“Sure. Sweet dreams.” He watched her go into her bedroom and listened to her undressing.

After a minute, he finished the glass of wine and took the bag into his room, to seek his own kind of consolation.

The valet woke them separately and led themboth to the garden, where La was sitting. It was full of night blossoms and their heavy fragrance, with dozens of large candles lending a warm light. She was wearing a white jumpsuit that revealed a spectacular, if virtual, figure.

She was sitting on a stone bench, and another one faced her. They sat down.

“You may stay here,” she said without preamble, “and live out the rest of your days in total comfort, and occasionally go down into the world for amusement. While I go on to explore the future. Or we can go together.”

“We were never sure,” Matt said, “whether the time machinewould work if someone else pushed the button. You might need me to come with you.”

“If I push the button, and nothing happens, we’ll have to work something out.”

“Like my thumbgoes, and the rest of me stays behind?”

“It would be an interesting experiment. I don’t think it would work.” There was no humor in her smile.

“But you can stay behind as well as go,” Matt said.

“Copies of me, aspects of me, will stay here, to run LA. But the part of me that goes on ahead is my essence. The part that’s here with you right now.”

“You could stay,” Matt said to Martha. “I got you into this, but there’s no reason you have to continue.”

“I’ve thought that through,” she said, “and prayed for guidance. I couldn’t stay here.”

“I don’t blame you,” La said. “This is one boring world. Matt might enjoy it for a while.” She gave him a knowing smile. “Almost any woman on this planet would be yours for the asking. But they really are boring.”

He saw Martha blush and lower her eyes. He hadn’t really thought of that aspect.

“They wouldn’t be ‘mine.’ But everybody here can’t be as vapid and silly as that couple.”

“Oh, really? There’s a kind of dead-end stability at work here, all over the civilized world. Everybody’s rich from birth, so there are no needy people complicating the situation. Anyone who tires of having everything can go off to the wilderness for as long as they can stand it, so the restless are taken care of.

“And I find myself with no challenges, either; nothing that isn’t dealt with automatically. So I’ve been sort of hoping that you would survive long enough to show up.”

“Of course,” Matt said. “You would know approximately when and where I would appear.”

“Maybe. We knew when and where you would land afteryou took the taxi—that was a daring move, and lucky– but there has been a cultural blackout in New England since 2181, so we couldn’t know whether you’d survived your contact with the Christers.”

“We wouldn’t have . . .” Martha began. “Sorry. Go on.”

“I had pretty sophisticated observation and analysis tools on the lookout for you in the here and now. But they weren’t necessary. When an ancient bottle of MIT wine went up for auction, that was all I needed.”

“How long have you been planning this?”

“Oh, I got the idea a couple of hundred years ago. Then just had to wait and see.”

“Did it ever occur to you that I might not wantcompany? Going into the future.”

“You need me. You know where the machine will take you next.”

“The Pacific Ocean.”

“You plan to go there in a bank vault?”

“I can get a metal boat.”

“Yes, and land in the middle of a typhoon and drown in seconds. Or just get lost at sea and dehydrate slowly.” She stood up. “Follow me.”

They went around a pond with luminous fish. “You need to find a backward time machine—both of you—and the only place you’ll find that is in the future. I can take you safely to that future. But then you go back, if you wish, and I go on.”

“All the way?”

“Whatever that means, yes.”

They walked down a flight of stone steps to a basement door. La pushed it open.

In the glare of a brilliant bluish light, a proper time machine. At first it looked like a huge mechanical insect, but that was just an all-terrain transportation system. Carried on top of and in between the four pairs of articulated legs were two containers, each about ten meters long, one with windows.

“Defense!” she said, and the bottom one was bristling with weapons. “Streamline!” The legs folded up around the machine, and a metal sheet slid around to enclose it in a seamless ovoid, which grew swept-back wings.

“I don’t think you could have built this, clever as you are with tools. But you’re going to need it. The jump after the next one will be into outer space.”

“ Maybe. The math is ambiguous.”

“In your time, maybe. No longer. Trust me—you don’t want to go out there in a taxicab or a bank vault.”

“Outer space?” Martha said. “Between the stars?”

“Well, between the planets. Stars come much later.

“I’ve doubled the life-support supplies to accommodate you, Martha. All I personally require is electricity, of course, and information. But I thought Matthew might like some human company.”

“Thank you,” they said simultaneously, and a startled look passed between them.

“Before we go, though, the people—well, callthem people—who helped me design and build this, asked a favor in return. We know so little about everyday life in your worlds—especially yours, Martha—that it would be extremely valuable if you would consent to a day of being interviewed. ”

“I don’t have any problem with that,” Matthew said, and looked into Martha’s silence.

“Is it just answering questions? In my time there were ‘interviews’ that had serious consequences.”

“That’s all you have to do, answer questions. They will measure your reaction to each question as well as record your answer.”

“Lie detecting?” Matt said.

“A little more subtle than that. Truth detecting, I suppose. ”

“Okay,” Matt said. He looked at Martha, and she nodded slowly.

“Good. They’ll be here in the morning, about ten. I’ll meet you for breakfast before that.” She disappeared.

They looked at their reflections in the machine’s mirror skin. “Truth detector,” he said.

“There are things I’d never tell anyone,” Martha confessed. “Do you think they could . . . make me do that?”

“I don’t know. But what difference would it really make? Everyone we ever knew is thousands of years dead.”

“La will know. We have to live with her.”

“Like I say, she’s seen everything. I doubt that you or I have ever done anything that would make her blink.”

She hugged herself. “God’s seen everything, too, in me. So I don’t really have any secrets.” She turned away from the machine. “Go back to the garden?”

It took both of them to pull the heavy door closed. The garden was unchanged, flowers and candles and the slightest breeze.

She sat down in the middle of one of the benches, and Matt sat across from her.

“I was reading about Bathsheba in the Bible,” she said.

“I don’t know the Bible.”

“People didn’t undress in front of each other in your time, did they?”

“Under some circumstances, yes. But not generally.”

“I grew up in a tenement that was very crowded,” she said. “The only privacy anyone had was in the toilet, and you didn’t waste time there, dressing. So people learned not to look? It was the same at the MIT dorm, but of course we were all girls.”

“I understand.”

“So I’m sorry if I was tempting you. I don’t know much about things like that.”

“It’s not a problem. Nothing could be fartherfrom being a problem.” She didn’t react. “So what did Bathsheba do that was so horrible?”

“Well, all she did was take a bath. But King David was looking down from the roof of his castle, and saw her, and summoned her, and they wound up committing adultery, and she got pregnant.

“Her husband, Uriah, was a soldier off fighting in a war. King David didn’t want him coming back to find Bathsheba pregnant, so he ordered Uriah’s commander to put him in a place where he would be killed.”

“That’s pretty low. But all Bathsheba did was take a bath.”

“And commit adultery.”

“Sure, but with the king? What would he have done to her if she’d said no?”

“When we studied that account in school, the teacher said she should have defied him, even it if meant her death. He showed us a picture, by Rembrandt, where she doesn’t look at all unwilling.”

“Well, yeah. Rembrandt was a guy, King David was a guy, your teacher was a guy, and the guys who wrote the Bible were all guys.”

“God wrote the Bible, and He is not a guy.”

“Okay. But Bathsheba was probably just trying not to get her head chopped off. Did her child inherit David’s kingdom?”

“No. The Lord took its life in its first year.”

“Yeah, that makes sense.”

The irony slid off Martha’s armor. “But then her next son was Solomon, who was an even greater king than David.”

“So God killed the first one because it was conceived in sin.” He shook his head. “But then David had the husband killed, so it wasn’t adultery anymore, and he let that one be king.”

“If you put it that way, it doesn’t sound very good. But the Lord moves in mysterious ways.”

“There’s no mystery. It’s like a big boys’ club! The men get the women and the power, and all the women get is screwed!”

She smiled behind her hand. “I don’t know that word. But I know what you mean by it.”

“None of your teachers ever talked about that?”

“Not yet, nothing specific.” She was serious again. “One of those things we have to put off until after Passage. If you had showed up a month later, I’d know a lot more.”

He sighed and stared at the ground between them. “I’m sorry. I came blundering in and knocked your life apart. When you’ve given me nothing but kindness.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” she said, almost lightheartedly. “I talked to God about it.”

“And he answered you?”

“Not in so many words—some people have that gift, but I don’t. Prayer just makes my mind clear and calm. I think He’s listening and guiding my thoughts.

“If you hadn’t come along, I would’ve had Passage next month, and probably been married a month after that, and be a mother next year sometime.”

“That’s the way it usually goes?”

“Usually. Unless a girl is really unpleasant or ugly, or ill.”

“No worries for you.”

“Probably not. But I have to say, and I told God, I wasn’t looking forward to it. That I didn’t feel old enough to be a mother. So you and your machine really were the answer to my prayers.”

“Are you crazy? I mean, no disrespect intended, but it might have been a little safer, getting married and settling down. We don’t know that we’ll ever find a way back.”

“We will, Professor. Matthew. You have to have faith.”

“You have enough for both of us.”

“But you said something when we were talking to Arl and Em. That you had evidence that somebody really had traveled back in time.”

“Circumstantial evidence.” She frowned at the term. “That’s something that provides an explanation, but without being actual proof.

“It was back in 2058. I was in trouble with the police—”

“Again?”

“Time travel does that to you. Anyhow, to get out of jail I needed an impossible amount of money, a million dollars. A lawyer I didn’t know showed up with it.

“I didn’t know anybody with that kind of money. But the lawyer said someone who looked somewhat like me had showed up at his office and given it to him, with instructions to come down to the courthouse and buy my way out.”

“So it was you, coming back from the future to save yourself.”

“It’s an explanation. But it requires backward time travel, which is supposed to be impossible.”

“That doesn’t sound very scientific, for a scientist. I’d say that the fact that you showed up with the money proves that backward time travel is possible—and it’s possible for you.” She stood up, excited. “And if you looked like you, now, we know it’s not going to take fifty years or something to find out the secret!”

“Or maybe it will take fifty years,” Matt said sardonically, “or a hundred, but traveling backward makes you look younger.” Her smile evaporated. “I’m kidding. Your logic is good. With that and your faith, how can we lose?”

“Thank you.” She dimpled again. “Are you hungry?”

“Starving. We should get something to eat, then rest. Sounds like a busy day tomorrow.” He looked around. “Mister Food Man?”

The valet appeared. “What may I do for you?”

“Can you do pizza?”

“Of course. New York or Chicago style?”

“New York. With pepperoni.”

He nodded and disappeared. “ ‘Piece of’?” Martha said. “Piece of what?”

“Pizza, with two zees. It’s from Italy.”

“It’s very good?”

“Oh, yeah.” Better than sex, he didn’t say, and at least I can introduce you to it in good conscience.

17

In the middle of a sound sleep, Matt suddenlywoke up. An unusually vivid dream.

Still there. He sat up and rubbed his eyes. It wouldn’t go away.

Why would he dream of Jesus?

He didn’t look like the Cambridge manifestation. Quieter, calming. He held one finger to his lips. Quiet. Don’t say anything. Don’t react.

Matt nodded microscopically.

I’m not even on your retina. This is a direct stimulation of the visual cortex and the parts of your brain that interpret hearing.