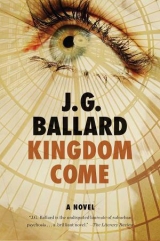

Текст книги "Kingdom Come: A Novel"

Автор книги: James Graham Ballard

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

Kingdom Come

James Graham Ballard

PART I

1

THE ST GEORGE’S CROSS

THE SUBURBS DREAM of violence. Asleep in their drowsy villas, sheltered by benevolent shopping malls, they wait patiently for the nightmares that will wake them into a more passionate world . . .

WISHFUL THINKING,I told myself as Heathrow airport shrank into the rear-view mirror, and more than a little foolish, an advertising man’s ingrained habit of tasting the wrapper rather than the biscuit. But they were thoughts that were difficult to push aside. I steered the Jensen into the slow lane of the M4, and began to read the route signs welcoming me to the outer London suburbs. Ashford, Staines, Hillingdon—impossible destinations that featured only on the mental maps of desperate marketing men. Beyond Heathrow lay the empires of consumerism, and the mystery that obsessed me until the day I walked out of my agency for the last time. How to rouse a dormant people who had everything, who had bought the dreams that money can buy and knew they had found a bargain?

The indicator ticked at the dashboard, a nagging arrow that I was certain I had never selected. But a hundred yards ahead was a slip road that I had somehow known was waiting for me. I slowed and left the motorway, entering a green-banked culvert that curved in on itself, past a sign urging me to visit a new business park and conference centre. I braked sharply, thought of reversing back to the motorway, then gave up. Always let the road decide . . .

LIKE MANY CENTRAL LONDONERS,I felt vaguely uneasy whenever I left the inner city and approached the suburban outlands. But in fact I had spent my advertising career in an eager courtship of the suburbs. Far from the jittery, synapse-testing metropolis, the perimeter towns dozing against the protective shoulder of the M25 were virtually an invention of the advertising industry, or so account executives like myself liked to think. The suburbs, we would all believe to our last gasp, were defined by the products we sold them, by the brands and trademarks and logos that alone defined their lives.

Yet somehow they resisted us, growing sleek and confident, the real centre of the nation, forever holding us at arm’s length. Gazing out at the placid sea of bricky gables, at the pleasant parks and school playgrounds, I felt a pang of resentment, the same pain I remembered when my wife kissed me fondly, waved a little shyly from the door of our Chelsea apartment, and walked out on me for good. Affection could reveal itself in the most heartless moments.

But I had a special reason for feeling uneasy—only a few weeks earlier, these amiable suburbs had sat up and snarled, then sprung forward to kill my father.

AT NINE THAT MORNING,a fortnight after my father’s funeral, I set off from London towards Brooklands, the town between Weybridge and Woking that had grown up around the motor-racing circuit of the 1930s. My father had spent his childhood in Brooklands and, after a lifetime of flying, the old airline pilot had returned there to pass his retirement. I was going to call on his solicitors, see that the probate of his will was under way, and put his flat up for sale, formally closing down a life that I had never shared. According to the solicitor, Geoffrey Fairfax, the flat was within sight of the disused racetrack, a dream of speed that must have reminded the old man of all the runways that still fled through his mind. When I packed away his uniforms and locked the door behind me, a last line would draw itself under the former British Airways pilot, an absentee parent I once hero-worshipped but rarely met.

He had left my strong-willed but highly strung mother when I was five, flown millions of miles to the most dangerous airports in the world, survived two attempted hijackings and then died in a bizarre shooting incident in a suburban shopping mall. A mental patient on day release smuggled a weapon into the atrium of the Brooklands Metro-Centre and fired at random into the lunch-hour crowd. Three people died, and fifteen were injured. A single bullet killed my father, a death that belonged in Manila or Bogotá or East Los Angeles, rather than in a bosky English suburb. Sadly, my father had outlived his relatives and most of his friends, but at least I had arranged the funeral service and seen him off to the other side.

As I left the motorway behind me, the prospect of actually turning the key in my father’s front door began to loom in the windscreen like a faintly threatening head-up display. A large part of him would still be there—the scent of his body on the towels and clothes, the contents of his laundry basket, the odd smell of old bestsellers on his bookshelves. But his presence would be matched by my absence, the gaps that would be everywhere like empty cells in a honeycomb, human voids that his own son had never been able to fill when he abandoned his family for a universe of skies.

The spaces were as much inside me. Instead of dragging around Harvey Nichols with my mother, or sitting through an eternity of Fortnum’s teas, I should have been with my father, building our first kite, playing French cricket in the garden, learning how to light a bonfire and sail a dinghy. At least I went on to a career in advertising, successful until I made the mistake of marrying a colleague and providing myself with a rival I could never hope to beat.

I reached the exit of the slip road, trailing a huge transporter loaded with micro-cars, each shiny enough to eat, or at least lick, toffee-apple cellulose brightening the day. The transporter paused at the traffic lights, an iron bull ready to rush the corrida of the open road, then thundered towards a nearby industrial estate.

Already I was lost. I had entered what the AA map represented as an area of ancient Thames Valley towns—Chertsey, Weybridge, Walton—but no towns were visible around me, and there were few signs of permanent human settlement. I was moving through a terrain of inter-urban sprawl, a geography of sensory deprivation, a zone of dual carriageways and petrol stations, business parks and signposts to Heathrow, disused farmland filled with butane tanks, warehouses clad in exotic metal sheeting. I drove past a brownfield site dominated by a massive sign announcing the Heathrow South extension with its unlimited freight capacity, though this was an empty land, where everything had already been sent on ahead. Nothing now made sense except in terms of a transient airport culture. Warning displays alerted each other, and the entire landscape was coded for danger. CCTV cameras crouched over warehouse gates, and filter-left signs pulsed tirelessly, pointing to the sanctuaries of high-security science parks.

A terrace of small houses appeared, hiding in the shadow of a reservoir embankment, linked to any sense of community only by the used-car lots that surrounded it. Moving towards a notional south, I passed a Chinese takeaway, a discount furniture warehouse, an attack-dog kennels and a grim housing estate like a partly rehabilitated prison camp. There were no cinemas, churches or civic centres, and the endless billboards advertising a glossy consumerism sustained the only cultural life.

ON MY LEFT,traffic moved down a side street, family saloons hunting for somewhere to park. Three hundred yards away, a line of shopfronts caught the sun. A suburban town had conjured itself from the nexus of access roads and dual carriageways. Rescue was offering itself to a lost traveller in the form of neon signs outside a chain store selling garden equipment and a travel agent advertising ‘executive leisure’.

I waited for the lights to change, an eternity compressed into a few seconds. The traffic signals presided like small-minded deities over their deserted crossroads. I lowered my foot onto the accelerator, ready to jump the red, and noticed that a police car was waiting behind me. Like the nearby town, it had materialized out of the empty air, alerted by the wayward imagination of an impatient driver in a powerful sports car. The entire defensive landscape was waiting for a crime to be committed.

TEN MINUTES LATERI eased myself onto a banquette in an empty Indian restaurant, somewhere in the centre of the off-motorway town that had come to my aid. Spreading my map over the elderly menu, a book of laminated pages unchanged for years, I tried to work out where I was. Vaguely south-west of Heathrow, I guessed, in one of the motorway towns that had grown unchecked since the 1960s, home to a population that only felt fully at ease within the catchment area of an international airport.

Here, a filling station beside a dual carriageway enshrined a deeper sense of community than any church or chapel, a greater awareness of a shared culture than a library or municipal gallery could offer. I had left the Jensen in the multi-storey car park that dominated the town, a massive concrete edifice of ten canted floors more mysterious in its way than the Minotaur’s labyrinth at Knossos—where, a little perversely, my wife suggested we should spend our honeymoon. But the presence of this vast structure reflected the truism that parking was well on the way to becoming the British population’s greatest spiritual need.

I asked the manager where we were, offering him the map, but he was too distracted to answer. A nervous Bengali in his fifties, he watched the traffic moving down the high street. Someone had thrown a brick at the plate-glass window, and the scimitar of a giant crack veered from ceiling to floor. The manager had tried to steer me into the rear of the empty restaurant, saying that the window table was reserved, but I ignored him and sat beside the fractured glass, curious to observe the town and its daily round.

The passers-by were too busy with their shopping to notice me. They seemed prosperous and content, confidently strolling around a town that was entirely composed of shops and small department stores. Even the health centre had redesigned itself as a retail space, its window filled with blood-pressure kits and fitness DVDs. The streets were brightly lit, cheerful and cleanly swept, so unlike the inner London I knew. Whatever the name of this town, there were no drifting newspapers and chewing-gum pavements, no citizenry of the cardboard box. This was a place where it was impossible to borrow a book, attend a concert, say a prayer, consult a parish record or give to charity. In short, the town was an end state of consumerism. I liked it, and felt a certain pride that I had helped to set its values. History and tradition, the slow death by suffocation of an older Britain, played no part in its people’s lives. They lived in an eternal retail present, where the deepest moral decisions concerned the purchase of a refrigerator or washing machine. But at least these Thames Valley natives with their airport culture would never start a war.

A pleasant middle-aged couple paused by the window, leaning against each other in a show of affection. Happy for them, I tapped the broken glass and gave a vigorous thumbs up. Startled by the apparition smiling a few inches from him, the husband stepped forward to protect his wife and touched the metal flag in the lapel of his jacket.

I had seen the flag as I drove into the town, the cross of St George on its white field, flying above the housing estates and business parks. The red crusader’s cross was everywhere, unfurling from flagstaffs in front gardens, giving the anonymous town a festive air. Whatever else, the people here were proud of their Englishness, a core belief no army of copywriters would ever take from them.

Sipping my flavour-free lager—another agency triumph—I studied the map as the manager hovered around my table. But I was in no hurry to order, and not merely because I had a shrewd idea of the sort of food on offer. The one fixed point on the map was my father’s flat in Brooklands, only a few miles to the south of where I sat. I could almost believe that he was waiting behind his desk, ready to interview me for a new post, the job of being his son.

What would he see, in those make-or-break thirty seconds when the interviewee entered his room? Applicant: Richard Pearson, forty-two years old, unemployed account executive. Likeable, but can seem slightly shifty. One-time secret smoker and former junior Wimbledon player with right elbow spur. Failed husband completely outwitted by his former wife. Good-humoured and optimistic, but privately a little desperate. He thinks of himself as a kind of terrorist, but all he is good at is warming the slippers of late capitalism. Applying for the post of son and heir, though very hazy about duties and entitlements . . .

I was very hazy, and not only about my father.

A WEEK BEFOREhis death I drove a close friend to Gatwick airport, at the end of my happiest months in many years. A Canadian academic on a year’s sabbatical, she was flying back to her job in the modern history department at Vancouver University. I liked her confidence and humour, and her frank concern for me. ‘Come on, Dick! Jump! Bale out!’ She talked of my joining her, perhaps finding work in the media studies department. ‘It’s an academic dustbin, but you can rattle the lid.’ She knew I had been eased out of the agency—my last campaign had been an expensive fiasco—and urged me to look hard at myself, never an inviting proposition. I started to miss her keenly a month before she left, and was more than tempted to pull the ripcord and join her.

Then, at the Gatwick departure gate, she discovered my passport in her handbag, zipped away in a side pocket since our return from a Rome weekend. Baffled, she stared at the war-criminal photo. ‘Richard . . . ? Who? Dick, my God! That’s you!’ She shrieked loudly enough to alert a security guard. I took this as a powerful unconscious signal. Vancouver and an escape into academia would have to wait. If someone who liked me and shared my bed could forget my name at the first glimpse of a departure lounge I needed urgently to reinvent myself. Perhaps my father would help me.

I finished my lager, watched by the manager, who had come to the window and was staring uneasily at the sky above the multi-storey garage. I was about to ask him about the St George’s badges worn by many of the passers-by, but he turned the ‘Closed’ sign to the street and retreated quickly to the rear of the restaurant. Sirens sounded, and groups of shoppers gazed up at the clouds of smoke floating across the precinct. Two police cars sped by, roof lights flashing.

Something had happened to disturb the deep consumerist peace. The manager disappeared into his kitchen, and a woman’s voice cried in alarm. Leaving enough cash to settle the bill, I folded the map, unlatched the door and let myself out of the restaurant. A fire engine bullied its way through the crowd, siren turning the air into a headache. I followed on foot, pushing past the pedestrians who stared at the darkening sky.

A few hundred yards from the town centre, near the road I had taken from the motorway, a car was burning on the perimeter of a modest council estate. Residents stood in their front gardens, arms folded as they watched the flames rise from a battered Volvo. A policeman discharged his fire extinguisher into the passenger cabin, while a fellow officer held back the crowd. They were staring at the shabby house of one of their neighbours, where a policewoman stood by the front door, gazing in a resigned way at the untended garden. Splashes of white paint traced a gaudy slogan over the masonry, and I assumed that an unpopular arrival had sullied the atmosphere of the estate, perhaps a released murderer or a paedophile exposed by the local vigilantes who had torched the car.

I eased my way through the onlookers, many still carrying their shopping bags, viewing the scene like an unexpected publicity display in a dull department store. Their expressions were hostile but wary, and they ignored the fire engine that pulled up behind them. They took their lead from three men in St George’s shirts who stood beside the gate, employees of a local hardware chain whose logo was stamped on their breast pockets. Their muscular, slightly paranoid presence reminded me of stewards at a football match, but there was no stadium anywhere nearby, and the only sport was taking place outside this seedy semi.

‘What’s going on? Is someone hiding inside . . . ?’ I spoke to a stocky woman muttering to herself as her wide-eyed daughter stared up at me. But my voice was drowned in the crowd’s roar. The villa’s door had opened, and a bearded man in turban and black robe stood on the step, beckoning to the anxious faces in the hall behind him. Above the door was a small ceramic plaque bearing an Arabic inscription, and I realized that this modest suburban house was a mosque. I was present at an outbreak of religious cleansing.

Instructed by the policewoman, the imam urged his followers into the garden. Three Asian youths in jeans and white shirts emerged into the light, followed by an elderly Pakistani man and a woman in a jellaba carrying a suitcase. Heads lowered, they moved through the now silent crowd, guarded by the firemen and police. As she passed me, the woman stumbled on the kerb, and I caught the stale, sweat-stained odour from her robe, the reek of fear.

I raised my hands to help her, but a strong shoulder knocked me off balance. Two of the hardware store assistants in St George’s shirts blocked my path, narrowed eyes staring over my head. I tripped onto one knee beside the Volvo, my hands pressed against a charred rag of plastic seating. Legs stepped over me, shopping bags swinging past my face. Without comment, the policewoman lifted me onto my feet, then walked me through the crowd to her car, where the imam sat alone in the back seat. His small congregation had vanished into the smoky air.

‘You’re with him?’ The policewoman opened the passenger door for me. ‘You can sit up front . . . ?’

‘No, no. I’m passing through. I’m a tourist.’

‘A tourist? We don’t get many of those.’ She slammed the door and turned away from me. ‘Next time try Brooklands Metro-Centre. Or Heathrow . . . everybody’s welcome there.’

I WALKED BACKto the car park, no longer surprised that the policewoman thought of a shopping mall and an airport as tourist attractions. I had witnessed a very suburban form of race riot, which had barely disturbed the peaceful commerce of the town. The shoppers grazed contentedly, like docile cattle. No voice had been raised, no stone thrown, and no violence displayed, except to the old Volvo and myself.

I drove out of the car park, following a sign that pointed to Shepperton and Weybridge, glad to be leaving this strange little town. I accepted that a new kind of hate had emerged, silent and disciplined, a racism tempered by loyalty cards and PIN numbers. Shopping was now the model for all human behaviour, drained of emotion and anger. The decision by the estate-dwellers to reject the imam was an exercise of consumer choice.

Everywhere St George’s flags were flying, from suburban gardens and filling stations and branch post offices, as this nameless town celebrated its latest victory.

2

THE HOMECOMING

JOURNEYS SELDOM END when I think they do. Too often a piece of forgotten baggage goes on ahead and lies in wait for me when I least expect it, circling an empty carousel like evidence being assembled before a trial.

Airports, arrivals and the departure of one old pilot filled my mind as I entered Brooklands an hour later. Around me was a prosperous Thames Valley town, a pleasant terrain of comfortable houses, stylish office buildings and retail parks, every advertising man’s image of Britain in the twenty-first century. I passed a bright new sports stadium like an open-air nightclub, display screens showing a road-safety commercial that merged seamlessly into an elegant pitch for a platinum credit card. Brooklands basked. Prosperity glowed from every roof shingle and gravel drive, every golden Labrador and teenage girl riding her well-trained nag.

But I was still thinking of the frightened Muslim woman being escorted from the tiny mosque, the acid stench of her robe and the smell of terror that no perfume could mask. Something had gone seriously wrong in the Thames Valley, and already I identified her with my father, another victim of a malaise even deeper than shopping.

Three weeks earlier my father—Captain Stuart Pearson, formerly of British Airways and Middle East Airlines—set off on one of his regular Saturday afternoon outings to the Brooklands Metro-Centre. Still vigorous at seventy-five, he walked the eight hundred yards to the retail complex that was the west of London’s answer to the Bluewater mall near Dartford. Joining the crowd of shoppers, he crossed the central atrium on his way to the tobacconist that stocked his favourite Dunhill leaf.

Soon after two o’clock, a deranged gunman opened fire on the crowd, killing three shoppers and wounding fifteen more. The gunman escaped in the confusion that followed, but the police soon arrested a young man, Duncan Christie, a day-release patient with a criminal record and a long history of public disturbance. He had carried out an eccentric campaign against the huge mall, and a number of witnesses saw him flee the scene.

My father was hit in the head by a single bullet, and lost consciousness as fellow shoppers tried to revive him. With the other wounded he was taken to Brooklands Hospital, then transferred by helicopter to the specialist neurology unit at the Royal Free Hospital, where he died the next day.

I had not seen my father for several years, and in the hospital mortuary failed to recognize the tiny, aged face that clung to the bony points of his skull. Given the fifteen years he had spent in Dubai, I expected almost no one to attend the funeral service at the north London crematorium. A group of elderly BA pilots saw him off, grey but stalwart figures with a million miles in their ever-steady eyes. There were no local friends from Brooklands, but his solicitor’s deputy, a sympathetic woman in her forties named Susan Dearing, arrived as the service began and handed me the keys to my father’s flat.

Surprisingly, there was a representative from the Metro-Centre, a keen young manager from the public relations office who introduced himself to everyone as Tom Carradine, and seemed to see even this morbid event as a marketing opportunity. Masking his professional smile with an effort, he invited me to visit the mall on my next trip to Brooklands, as if something good might still come from the tragedy. I guessed that attendance at the funerals of shoppers who had died on the premises was part of the mall’s after-sales service, but I was too distracted to brush him off.

Two young women slipped into a rear pew as the recorded voluntary groaned from a concealed vent, a music that only the dead could appreciate, the sound of coffins straining like the timbers of storm-tossed galleons. One of the women laughed as the chaplain launched into his homily. Knowing nothing of my father, he was forced to recite the endless scheduled routes that Captain Pearson had flown. ‘The next year Stuart found himself flying to Sydney . . .’ Even I let out a giggle at this.

The women left as soon as the service ended, but I caught one of them watching me from the car park as the friend hunted for her keys. Dark-haired, with the kind of dishevelled prettiness that unsettles men, she was too young to be one of my father’s girlfriends, but I knew nothing about the old sky-dog’s last days. She waited irritably when her friend fumbled with the door lock, and tried to hide in the passenger seat. As their car passed she looked at me and nodded to herself, clearly wondering if I was too louche or too frivolous to match up to my father. For some reason I was sure that we would see each other again.

THE TRAFFIC INTOBrooklands had slowed, filling the six-lane highway built to draw the population of south-east England towards the Metro-Centre. Dominating the landscape around it, the immense aluminium dome housed the largest shopping mall in Greater London, a cathedral of consumerism whose congregations far exceeded those of the Christian churches. Its silver roof rose above the surrounding office blocks and hotels like the hull of a vast airship. With its visual echoes of the Millennium Dome in Greenwich, it fully justified its name, lying at the heart of a new metropolis that encircled London, a perimeter city that followed the path of the great motorways. Consumerism dominated the lives of its people, who looked as if they were shopping whatever they were doing.

Yet there were signs that a few serpents had made their home in this retail paradise. Brooklands was an old county town, but in the poorer outskirts I passed Asian shops that had been vandalized, newsagents boarded up and plastered with St George’s stickers. There were too many slogans and graffiti for comfort, too many BNP and KKK signs scrawled on cracked windows, too many St George’s flags flying from suburban bungalows. Never far from the defensive walls of the motorways, there was more than a hint of paranoia, as if these people of the retail city were waiting for something violent to happen.

UNABLE TO BREATHEinside the low-slung Jensen, I opened the window, preferring the roadside microclimate of petrol and diesel fumes. The traffic unpacked itself, and I turned left at the sign ‘Brooklands Motor Museum’, moving down an avenue of detached houses behind high walls. My father had made his last home in a residential complex of three-storey apartment buildings in a landscaped park, reached by a narrow lane off the main avenue. As I drove between the privet walls I was still trying to prepare a few pat answers for the ‘interview’ that would decide my fitness for the post of his son, an application that had been turned down nearly forty years earlier.

Unconsciously I reapplied for the post whenever I met him—he was always affectionate but distant, as if he had run into a junior member of an old cabin crew. My mother sent him details of my school reports, and later my LSE graduation photograph, but only to irritate him. Luckily, I lost interest in him during my teens, and last saw him at the funeral of my stepmother, when he was too distressed to speak.

I had always wanted him to like me, but I thought of the single piece of baggage on the deserted carousel. How would I react if I found a framed photograph of myself on his mantelpiece, and an album lovingly filled with cuttings from Campaignabout my then successful career?

Holding the door keys in my hand, I stepped from the car and walked across the deep gravel to the entrance, half expecting the neighbours to emerge from their flats and greet me. Surprisingly, not a window or curtain stirred, and I climbed the stairs to the top-floor landing. After a count of five, I turned the key and let myself into the hallway.

THE CURTAINS WEREpartly drawn, and the faint light seemed to illuminate what was unmistakably a stage set. This was an old man’s flat, with its leather armchair and reading lamp, pipe rack and humidor. I almost expected my father to appear on cue, walk to the rosewood drinks cabinet and pour himself a Scotch and soda, take a favourite volume from the bookshelf and peruse its pages. It needed only the telephone to ring, and the drama would begin.

Sadly, the play had ended, and the telephone would never ring, or not for my father. I tried to wave the scene away, annoyed with my own flippancy, a professional habit of trivializing the whole of life into the clichés of a TV commercial. The unopened mail on the hall table struck a more sombre note. Curiously, several envelopes carried black bands and were addressed to my father, as if he himself would read them.

I walked across the sitting room and drew the curtains. The bright garden light flooded through the scent of stale tobacco and staler memories. In front of me, looming across the houses and office buildings, was the silver dome of the Metro-Centre, dominating the landscape to the west of London. For the first time I realized that its presence was almost reassuring.

FOR THE NEXThour I moved around the flat, opening desk drawers and kitchen cupboards, like a burglar trying to strike up a relationship with a householder whose home he was ransacking. I was introducing myself to my father, even though I was paying him a rather late visit. I shook my head a little sadly over his spartan bedroom with its narrow mattress, part of a widower’s self-denial. Here an old man had dreamed his last dreams of flight, a reverie of wings that overflew deserts and tropical estuaries. I opened the wardrobe and counted his six uniform suits, hanging together like an entire flight crew of senior captains. On the dressing table was a set of silver-backed hairbrushes that I assumed he had given to my stepmother, memories that would greet him each morning of this gaunt but still glamorous woman. Another memory of married years was an ancient bottle of Chanel, contents long evaporated. Pressing the cap, I picked out a faint scent, echoes of a much-loved skin.

In the bathroom I opened the medicine cabinet, expecting to find a small warehouse of vitamin supplements. But the shelves were bare apart from a denture wash and a packet of senna pods. The old man had kept himself fit, using the rowing machine and exercise cycle in the spare bedroom. In the utility room beyond the kitchen was an ironing board and a table with the maid’s electric kettle and biscuit tin. Behind the piles of ironing and a row of heavily starched shirts was a workspace with a computer and printer, a few books stacked beside it.

I went back to the sitting room and scanned the shelves, with their rows of popular novels, cricket almanacs and restaurant guides to airline destinations: Hong Kong, Geneva, Miami. At some point I would go through his desk, hunting out share certificates, bank statements, tax returns, and assemble a financial picture of the estate he had left, money more than useful now that I was unemployed and likely to remain so.