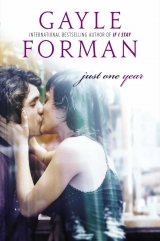

Текст книги "Just One Year"

Автор книги: Gayle Forman

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

Thirteen

Deauville

It’s off season in Deauville, and the seaside resort is buttoned up tight, a cold wind whipping in off the Channel. From a distance, I can see the marina, rows of sailboats in drydock, on their stands, their masts unstepped. As we get closer, the whole marina appears shut down, hibernating for the winter. Which seems about the right idea.

On the drive down in Lien’s car, which had smelled of lavender when we left and now smells of wet, dirty laundry somehow, the boys had been ebullient. W had located a barge called Violalate last night and had then decided we should take a road trip to France. “Wouldn’t it be easier to call?” I’d asked after the plan had been explained to me. But no. They seemed to think we should just go. Of course, they were properly dressed for it, and I was in nothing but a thin tracksuit. And they had nothing to lose, except a day’s worth of studies. Me, I had even less, but it felt like more somehow.

We drive around the labyrinthine marina, finally reaching the main office only to find it closed. Of course. It’s now four o’clock on a dark November day; anyone in their right mind is holed up somewhere warm.

“Well, we’ll just have to find it ourselves,” W says.

I look around. As far as I can see in every directions are masts. “I don’t see how.”

“Are marinas organized by type of vessel?” W asks.

I sigh. “Sometimes.”

“So there might be a section for barges?” he prompts.

I sigh again. “Possibly.”

“And you said this Jacques lives on his boat year-round so it wouldn’t be drydocked?”

“Probably not.” We had to pull our houseboat out of the water every four years for service overhauls. Drydocking for a vessel that size is a massive undertaking. “Probably anchored.”

“To what?” Henk asks.

“Probably to a pier.”

“There. We walk around until we find the barges,” W says, as if it’s all that easy.

But it’s not easy at all. It’s raining hard now, wet below us and above us. And it seems deserted around here, no sound except the steady pounding of rain, the waves against the sides of the hulls, and the clang of the halyards.

A cat streaks out across one of the piers, and behind it, a barking dog, and behind the dog, a man in a yellow slicker, one dot of color in all the gloom. I watch them go and wonder if I’m like that dog, chasing a cat because it’s what a dog does.

The boys take shelter under an awning. I’m shivering now, ready to pack it in. I turn around to suggest a warm bistro, a nice meal, and some drinks before the long drive home. But the boys are all pointing behind me. I turn back around.

The Viola’s blue steel shutters are closed, making her look lonely out here strapped alongside the cement slips and the massive wooden posts. She looks cold, too, like she also wishes she were back in the hot Paris summer.

I step on the pier, and for a second, I can almost feel the rays of sunlight on my skin, can hear Lulu introducing me to double happiness. It was right there we’d sat, by the railing. Right there we’d disagreed about what double happiness meant. Luck, she’d said. Love, I’d countered.

“What the hell are you doing here?”

Striding toward us is the man in the yellow slicker, the runaway mutt now leashed and shivering.

“Many a thief has underestimated Napoleon and has paid for it in a pound of flesh, haven’t they?” the man says to his dog. He pulls at the leash and Napoleon barks pitifully.

“I’m not a thief,” I say in French.

The man wrinkles his nose. “Worse! You are a foreigner. I knew you were too tall. German?”

“Dutch.”

“No matter. Get out of there before I call the gendarme or let Napoleon loose on you.”

I hold up on my hands. “I’m not here to steal anything. I’m looking for Jacques.”

I’m not sure if it’s the dropping of Jacques’s name or the fact that Napoleon has started licking his balls, but the man backs down. “You know Jacques?”

“A little.”

“If you know Jacques even a little, you know where to find him when he’s not on the Viola.”

“Maybe less than a little. I met him last summer.”

“You meet lots of people. You don’t board a man’s vessel without an invitation. That is the ultimate violation of his kingdom.”

“I know. I just want to find him, and this is the only place I can think of.”

He squints. “Does he owe you money?”

“No.”

“You’re sure? This isn’t about the races? He always backs the wrong horses.”

“Nothing to do with that.”

“Did he sleep with your wife?”

“No! Last summer he took four passengers through Paris.”

“The Danes? Bastards! He lost almost his whole charter fee right back to them. He’s a terrible poker player. Did he lose money to you?”

“No! He got money off us. A hundred dollars. Me and this American girl.”

“Terrible, those Americans. They never speak French.”

“She spoke Chinese.”

“What good does thatdo you?”

I sigh. “Look, this girl . . .” I start to explain. But he waves me away.

“If you want Jacques, go to Bar de la Marine. When he’s not on the water, he’s in the drink.”

• • •

I find Jacques at the long wooden bar, slung over a near-empty glass. As soon as we walk in, he waves at me, though whether it’s because he recognizes me or because this is just his standard greeting, I’m not sure. He is carrying on an in-depth conversation about new slip fees with the bartender. I buy the boys a round of beers, settle them into a corner table, and sit down next to Jacques.

“Two of what he’s having,” I tell the bartender, and he pours us each a glass of teeth-achingly sweet brandy on the rocks.

“Good to see you again,” Jacques tells me.

“So you remember me?”

“Of course I remember you.” He squints, placing me. “Paris.” He belches and then pounds his chest with his fist. “Don’t look so surprised. It was only a few weeks ago.”

“It was three months ago.”

“Weeks, months. Time is so fluid.”

“Yes, I remember you saying that.”

“You want to charter the Viola? She’s dry for the season but we get wet again in May.”

“I don’t need a charter.”

“So what can I do for you?” He downs the rest of his drink and crunches hard on the ice. Then he starts in on the fresh one.

I don’t really have an answer for him. What canhe do for me?

“I was with that American girl and I’m trying to get in touch with her. She didn’t by any chance get in touch with you?”

“The American girl. Oh yes, she did.”

“Really?”

“Yeah. She said to tell that tall bastard I’m done with him ’cause I’ve found myself a new man.” He points to himself. Then he laughs.

“So she didn’t get in touch with you?”

“No. Sorry, boy. She leave you high and dry?”

“Something like that.”

“You could ask those bastard Danes. One of them keeps texting me. Let me see if I can find it.” He pulls out a smartphone and starts fumbling with it. “My sister got me this, said it would help with navigation, bookings . . . but I can’t figure it out.” He hands it to me. “You try.”

I check his text queue and find a note from Agnethe. I open the text and there are several more before it, including pictures from last summer when they were cruising on the Viola. Most are of Jacques, in front of fields of yellow safflower, or cows, or sunsets, but there’s one shot I recognize: a clarinet player on a bridge over Canal Saint Martin. I’m about to hand the phone back when I see it: in the corner, a sliver of Lulu. It’s not her face, it’s the back of her—shoulders, neck, hair—but it’s her. A reminder that she’s not some fiction of my own making.

I’ve often wondered how many photos I’ve been accidentally captured in. There was another photo that day, not accidental at all. An intentional shot of Lulu and me that she’d asked Agnethe to take with her phone. Lulu had offered to send it to me. And I’d said no.

“Can I forward this to myself?” I ask Jacques.

“As you wish,” he says, with a wave of the hand.

I forward the shot to Broodje’s phone because it was true that mine won’t accept photo texts, though that wasn’t the reason I didn’t want the shot of Lulu and me when she offered it. It was automatic, that denial, a reflex almost. I had almost no pictures from the last year of my traveling. Though I’m sure I am in many people’s photos, I’m in none of my own.

In my rucksack, the one that got stolen on that train to Warsaw, had been an old digital camera. And on that camera were photographs of me and Yael and Bram from my eighteenth birthday. They were some of the last photos I had of the three of us together, and I hadn’t even discovered them until I was on the road, bored one night and going through all the shots on my memory stick. And there we were.

I should’ve had those pictures emailed somewhere. Or printed. Done something permanent. I planned to, I did. But I put it off and then my rucksack got nicked and it was too late.

The devastation caught me off guard. There’s a difference between losing something you knew you had and losing something you discovered you had. One is a disappointment. The other is truly a loss.

I didn’t realize that before. I realize it now.

Fourteen

Utrecht

On the ride back to Utrecht, I call Agnethe the Dane to see if Lulu sent her any photographs, if there had been any correspondence. But she hardly remembers who I am. It’s depressing. This day, so seared in my memory, is just another day to everyone else. And in any case, it was just one day, and it’s over now.

It’s over now with Ana Lucia, too. I can feel it, even if she can’t. When I come back, defeated, telling her soccer season is over, she is sympathetic, or maybe victorious. She’s full of kisses and cariños.

I accept them. But I know now it’s just a matter of time. In three weeks, she leaves for Switzerland. By the time she gets back, four weeks later, I will be gone. I make a mental note to get on that passport renewal.

It’s as if Ana Lucia senses all this. Because she starts pushing harder for me to join her in Switzerland. Every day, a new appeal. “Look how nice the weather is,” she says one morning as she gets ready for class. She opens her computer and reads me the weather report from Gstaad. “Sunny skies every day. Not even so cold.”

I don’t answer. Just force a smile.

“And here,” she says, clicking over to a travel site she likes and tilting the laptop toward me to show me pictures of snowy alps and painted nutcrackers. “Here it shows you all the things you can do besides skiing. You don’t have to sit at the lodge. We’re close to Lausanne or Bern. Geneva’s not even so far. We can go shopping there. It’s famous for watches. I know! I’ll buy you a watch.”

My whole body stiffens. “I already have a watch.”

“You do? I never see you wear it.”

It’s back at Bloemstraat, in my rucksack. Still ticking. I can almost hear it from here. And suddenly, three weeks feels too long.

“We should talk.” The words trip out before I know what to follow them with. Breaking up is not something I’ve done in a while. So much easier to kiss good-bye and catch a train.

“Not now,” she says, rising to apply lipstick in the mirror. “I’m already late.”

Okay. Not now. Later. Good. It will give me time to find the right words. There are always right words.

• • •

After she leaves, I get dressed, make a coffee, and sit down at her computer to check my email before I leave. The travel page she was on is still open, and I’m about to close the window when I see one of the banner ads. MEXICO!!! it screams. Outside, it’s cold and gray, but the pictures promise only warmth and sunshine.

I click on the link, and it takes me to a page listing several package holiday specials, not the kind of thing I’d ever do, but I feel warmer just looking at the beaches. And then I see some ads for trips to Cancún.

Cancún.

Where Lulu goes every year.

Where she has gone with her family to the same place every year. Her mother’s predictability, so exasperating to her, is now my best hope.

I pull up the details. Like everything from that day, they’re as fresh as wet paint. A resort fashioned like a Mayan temple. Like America behind walls with Christmas carols mariachi– style. Christmas. They went for the holidays. Christmas. Or was it New Year’s? I can just go for both!

Channeling W, I start searching for resorts in Cancún. One crystalline-water beach after the other flashes across the screen. There is no end to them, these megaresorts like Mayan fortresses and temples. She said it had some kind of river. I’d remembered wondering about that, a resort with a river. There aren’t any natural rivers running through Cancún. There are golf courses and swimming pools and diving cliffs, and waterslides. But rivers? I’m looking at the listing for Palacio Maya when I stumble across it. A lazyriver, a kind of fake stream you ride on in an inflatable tube.

I narrow my search. There don’t seem to be thatmany resorts that look like Mayan temples and have lazy rivers. Four, that I can see. Four that Lulu might be staying at some time between Christmas and New Year’s.

Outside it’s pouring, but the sites brag that the weather in Mexico is hot, endless blue skies and sunshine. All this time, I’ve been stuck, trying to figure out where to go next. Why not here? To find her? I click over to an airline consolidator and look up the prices for two tickets to Cancún. Expensive, but then again, I can afford it.

I snap the computer shut, a list forming in my head. It seems so simple.

Get my passport.

Invite Broodje.

Buy the tickets.

Find Lulu.

Fifteen

By six o’clock that night, I’ve bought Broodje’s and my plane tickets and reserved us a room at a cheap hotel in Playa del Carmen. I feel flush with satisfaction, having accomplished more in this single day than I have in the last two months. There’s only one thing left to do.

“We need to talk,” I text Ana Lucia. She texts me right back, “I know what you want to talk about. Come by at 8.” I am limber with relief. Ana Lucia is smart. She knows, like I know, that whatever this is, it’s not a stain.

I buy a bottle of wine on my way over. No reason this can’t be civilized.

She greets me at the door, wearing a red bikini and redder lips. Taking the wine from my hand, she pulls me inside. There are lit votive candles everywhere, like a cathedral on a saint’s day. I get a bad feeling.

“Cariño, I understand it now. All that talk about how much you hate the cold. I should’ve guessed.”

“You should’ve guessed?”

“Of course you want to go somewhere warm. And you know my aunt and uncle are in Mexico City but what I can’t figure out is how you know about the villa on Isla Mujeres?”

“Isla Mujeres?”

“It’s beautiful. Right on the beach, with a pool and servants. They have invited us to stay there if we want, or we can stay on the mainland, though not at one of those cheap places,” She wrinkles her nose. “I insist to pay for the hotel, no arguments. Because it’s only fair you bought the tickets.”

“Bought the tickets.” All I can do is repeat.

“Oh cariño,” she coos. “You’ll meet my family, after all. They are going to throw us a party. My parents were upset about me canceling Switzerland but they understand the things you do for love.”

“For love,” I repeat although with a sickening feeling I’m starting to piece together what has happened. Her Internet browser. My entire search history. Tickets for two. The hotel. My smile is pulled taut, full of false sweetness. How can I find the words for this? A misunderstanding, I will tell her; the tickets are for a boys’ holiday, for me and Broodje, which istrue.

“I know you wanted it to be a surprise,” she continues. “Now I know why you have been sneaking off on the telephone, but amor, we leave in three weeks, when did you plan to tell me?”

“Ana Lucia,” I begin. “There’s been a misunderstanding.”

“What do you mean?” she says. And the hope is still there, as if the misunderstanding is about a minor detail, like the hotel.

“Those tickets. They’re not for you. They’re for—”

She cuts me off. “It’s that other girl isn’t it? The one from Paris?”

Maybe I’m not so good an actor as I think. Because the way her expression has tectonically shifted from adoration to suspicion shows me that she’s probably always known. And I must be a terrible actor now, because even as my mouth starts to form a plausible explanation, my face must be giving it all away. I can tell it is by what’s happening to Ana Lucia’s face—her pretty features puckering into disbelief, and then into belief.

“ Hijo de la gran puta!It’s the French girl? You’ve been with her all this time, haven’t you?” Ana Lucia screams. “ That’swhy you went to France?”

“It’s not what you think,” I say holding up my hands.

She flings open the sliding-glass door leading onto the quad. “It’s exactly what I think,” she says, shoving me out the door. I just stand there. She reaches for a candle and hurls it at me. It flies past me and lands on one of the throw pillow she keeps on the cement stoop. “You’ve been sneaking around all this time with that French whore!” Another candle whizzes by, landing in the shrubbery.

“You’re going to start a fire.”

“Good! I’ll burn the memory of you, culero!” She flings another candle at me.

The rain has stopped, and though it’s a chilly night, it seems as if half the college has now gathered around us. I try to bring her back inside, to calm her down. I am unsuccessful at both.

“I canceled my trip to Switzerland for you! My relatives arranged a party for you. And all along, you were sneaking off to see your French whore. In my land. Where my family lives.” She pounds on her bare chest, as if she’s claiming ownership not just of Spain but of all of Latin America.

She hurls another candle. I catch this one, and it explodes, spilling glass and hot wax down my hand. My skin bubbles to a blister. I wonder, vaguely, if it’ll scar. I suspect it won’t.

Sixteen

DECEMBER

Cancún

The height of the Mayan civilization was more than a thousand years ago, but it’s hard to imagine the holiest of temples back then were as well guarded as the Maya del Sol is now.

“Room number?” The guards ask Broodje and me as we approach the gate in the imposing carved wall that seems to stretch a kilometer in each direction.

“Four-oh-seven,” Broodje says before I have a chance to speak.

“Key card,” the guard says. There are sweat patches all down the side of his sweater vest.

“Um, I left it in the room,” Broodje replies.

The guard opens a binder and looks through a sheaf of papers. “Mr. and Mrs. Yoshimoto?” he asks.

“Uh-huh,” Broodje replies, linking arms with me.

The guard looks annoyed. “Guests only.” He snaps the binder shut and goes to close the little window.

“We’re not guests,” I say, smiling conspiratorially. “But we’re trying to finda guest.”

“Name?” He picks up the binder again.

“I don’t know, exactly.”

A black Mercedes with tinted windows glides up and barely stops before the guards lift the gate and wave it through. The guard turns back to us, weary, and for a second I think we’ve won. But then he says, “Go now, before I have to call the police.”

“The police?” Broodje exclaims. “Whoa, whoa, whoa. Let’s just all cool down a minute. Take off our sweater vests. Maybe have a drink. We can go to the bar; the hotel must have some nice bars. We’ll bring you back a beer.”

“This is not a hotel. It’s a vacation club.”

“What does that mean, exactly?” Broodje asks.

“It means you can’t come in.”

“Have a heart. We came from Holland. He’s looking for a girl,” Broodje says.

“Aren’t we all?” the guard behind him asks, and they both laugh. But they still don’t let us in.

I give the moped a good frustrated kick, which at least means it sputters to life. Nothing so far is going quite how I’d expected it to, not even the weather. I’d thought Mexico would be warm, but it’s like being in an oven all day long. Or maybe it only feels that way because instead of spending our first day on a breeze-cooled beach as Broodje had the good sense to do, I spent yesterday at the Tulum ruins. Lulu had mentioned her family went to the same ruins every year and Tulum is the closest one, so I’d thought I might just catch her there. For four hours I watched thousands of people as they belched out of tour buses and minivans and rental cars. Twice, I thought I saw her and ran after a girl. Right hair, wrong girl. And I realized she might not even have that haircut anymore.

I’d come back to our little hotel with a sunburn and a headache, the optimism I’d had about this trip souring into a sinking feeling. Broodje cheerfully suggested we try the hotels, a more contained environment. And if that didn’t work out, he’d pointed toward the beach. “There are so many girls here,” he’d said in a hushed, almost reverent tone, gesturing out to the sand, which was covered, every square yard of it, with bikinis.

So many girls, I’d thought. Why am I trying to find just one?

• • •

Palacio Maya, another of the faux-Mayan resorts on my hit list, is a few kilometers north of here. We putter up the highway, breathing in the fumes of the passing tour buses and trucks. This time, we stash the moped in some flowering shrubs along the winding manicured road that leads to the front gates. Palacio Maya looks a lot like the Maya del Sol, only instead of a monolithic wall, it is fronted by a giant pyramid, with a guard gate in the middle. This time, I’m ready. In Spanish, I tell the guard I’m trying to find a friend of mine who’s staying here but I want to surprise her. Then I slip him a twenty-dollar bill. He doesn’t say a word—he just opens the gates.

“Twenty dollars,” Broodje says, nodding his head. “Much classier than a couple of beers.”

“It’s probably what a couple of beers go for in a place like this.”

We walk along the paved roadway, expecting to find a hotel, or some evidence of one, but what we find is another guard gate. The guards smile at us and call buenos días, as if they’re expecting us, and by the way they’re appraising us, like they’re cats and we’re mice, I see the other guards have called ahead. Without saying a word, I reach into my wallet and hand over another ten.

“Oh gracias, señor,” the guard says. “ Que generoso!” But then he looks around. “Only there are two of us.”

I reach back into my wallet. The well’s dry. I show my empty wallet. The guard shakes his head. I realize I overplayed it back at the first gate. I should’ve offered up the ten first.

“Come on,” I say. “It’s all I have left.”

“Do you know how much rooms here are?” he asks. “Twelve hundred dollars a night. If you want me to let you in, and your friend, to enjoy the pools, the beaches, the tennis, the buffets, you have to pay.”

“ Buffets?” Broodje interrupts.

“Shh!” I whisper. To the guard I say, “We don’t care about any of that. We’re just trying to find a guest here.”

The guard raises his eyebrow. “If you know guests, why you sneak in like a thief? You think just because you have white skin, and a ten-dollar bill, we think you are rich?” He laughs. “It’s an old trick, amigo.”

“I’m not trying to sneak anything. I’m trying to find a girl. An American girl. She might be staying here.”

This makes the guard laugh even harder. “An American girl? I’d like one of those, too. They cost more than ten dollars.”

We glare at each other. “Give me my money back,” I say.

“What money?” the guard asks.

I’m furious when we get back to the bike. Broodje, too, is muttering about getting ripped off that thirty dollars. But I don’t care about the money, and it’s not the guards I’m mad at.

I keep replaying a conversation with Lulu in my head. Then one when she’d told me about Mexico. About how frustrating it was to go to the same resort with her family every year. I’d told her maybe she should go off the grid next time she went to Cancún. “Tempt fate,” I’d said. “See what happens.” Then I’d joked that maybe I’d go to Mexico one day, too, bump into her, and we’d escape into the wilds, having no idea at the time that this silly aside would become a mission of sorts. “You think that would happen?” she’d asked. “We’d just randomly bump into each other?” I’d told her it would have to be another big accident and she’d teased back: “So you’re saying I’man accident?”

After I told her that she was, she’d said something strange. She’d said that me calling her an accident might be the most flattering thing anyone has ever said about her. She wasn’t simply fishing for compliments. She was revealing something with that honesty of hers, so completely disarming it was like she was stripping not just herself bare but me, too. When she said that, it had made me feel as if I’d been entrusted with something very important. And it also made me sad, because I sensed it was true. And if it was, it was wrong.

I’ve flattered lots of girls, many who deserved it, many who didn’t. Lulu deserved it, she deserved so much more flattery than being called an accident. So I opened my mouth to say something nice. What came out, I think, surprised us both. I told her that she was the sort of person who found money and returned it, who cried in movies you weren’t meant to cry in, who did things that scared her. I wasn’t even sure where these things were coming from, only that as I said them, I was certain that they were true. Because improbable as it was, I knewher.

Only now it strikes me how wrong I was. I didn’t know her at all. And I didn’t ask the simplest of questions, like where she stayed in Mexico or when she visited or what her last name was, or what her first name was. And as a result, here I am, at the mercy of security guards.

We ride back to our hostel in the dusty part of Playa del Carmen, full of stray dogs and rundown shops. The cantina next door serves cheap beer and fish tacos. We order several of each. A couple of travelers from our hostel roll in. Broodje waves them over, and he starts telling them about our day, embellishing it so that it almost sounds fun. It’s how all good travel stories are born. Nightmares spun into punch lines. But my frustration is too fresh to make anything seem funny.

Marjorie, a pretty Canadian girl, clucks sympathetically. A British girl named Cassandra, with short spiky brown hair, laments the state of poverty in Mexico and the failures of NAFTA, while T.J., a sunburnt guy from Texas, just laughs. “I seen that place Maya del Sol. It’s like Disneyland on the Riviera.”

At the table behind us, I hear someone snicker. “ Más como Disneyland del infierno.”

I turn around. “You know the place?” I ask in Spanish.

“We work there,” the taller one answers in Spanish.

I put out my hand. “Willem,” I say.

“Esteban,” he answers.

“José,” says the shorter. They’re a bit of a spaghetti-and-meatball pair, too.

“Any chance you can sneak me in?”

Esteban shakes his head. “Not without risking my job. But there’s an easy way to get in. They’ll pay you to visit.”

“Really?”

Esteban asks me if I have a credit card.

I pull out my wallet and show him my brand new Visa, a gift from the bank after my large deposit.

“Okay, good,” Esteban says. Then he looks at my outfit, a t-shirt and a beat-up pair of kakis. “You’ll also need better clothes. Not these surfer things.”

“No problem. Then what?”

Esteban explains how Cancún is full of sales reps trying to get people into those resorts to buy a timeshare. They hang out at car-rental places, in the airports, even at some of the ruins. “If they think you havemoney, they’ll invite you to take a tour. They’ll even pay youfor your trouble, money, free tours, massages.”

I explain this all to Broodje.

“Sounds too good to be true,” he says.

“It’s no too good, and it is true,” José answers in English. “So many people buy, make such a big decision after just one day.” He shakes his head, in wonderment, or disgust, or both.

“Fools and their money,” T.J. says, laughing. “So y’all gotta look like you’re loaded.”

“But he isloaded!” Broodje says. “What does it matter what he looks like?”

José says, “No matter what you is; only matter what you seem.”

• • •

I buy Broodje and myself some linen pants and button-up shirts for next to nothing and spend a ridiculous amount on a couple of pairs of Armani sunglasses from one of the stalls in the touristy section of town.

Broodje is aghast at the cost of the glasses. But I tell him they’re necessary. “It’s the little details that tell the big story.” That was what Tor always said, to explain why we had such minimal costumes in Guerilla Will.

“What’s the big story?” he asks.

“We’re slacker playboys with trust funds, renting a house on Isla Mujeres.”

“So, aside from the house, you’re pretending to be you?”

• • •

The next day is Christmas so we wait until the day after to set off. At the first car rental agency, we’ve practically rented a car by the time we realize that there’s no one there offering us a tour. At the second car rental agency, we’re met by a smiling, big-toothed American blonde who asks us how long we’re in town for and where we’re staying.

“Oh, I love the Isla,” she purrs after we tell her about our villa. “Have you eaten at Mango yet?”

Broodje looks mildly panicked but I just give a little smile. “Not yet.”

“Oh,” she says. “Does your villa come with a cook?”

I just continue to smile, a little bashfully this time, as if the largesse embarrasses me.

“Wait. Are you renting the white adobe place with the infinity pool?”

Again, I smile. Little nod.

“So Rosa is the cook there?”

I don’t answer, I don’t need to. An embarrassed shrug will do.

“Oh, I lovethat place. And Rosa’s mole is divine. Just thinking about it makes me hungry.”

“I’m always hungry,” Broodje says, leering. She looks at him quizzically. I give him a discreet kick.

“That place is very expensive,” she says. “Have you ever considered buying something down here?”

I chuckle. “Too much responsibility,” says Willem, Millionaire Playboy.

She nods, as if she too understands the burdens of juggling multiple properties. “Yes. But there is another way. You can own, and have someone else take care it for you, even rent it out for you.” She pulls out glossy brochures of several different hotels—including the Maya del Sol.

I glance at the brochures, scratching my chin. “You know, I heard about such an investment for tax-sheltering purposes,” I say, channeling Marjolein now.

“Oh, fantastic moneymaker and money saver. You really should see one of these properties.”