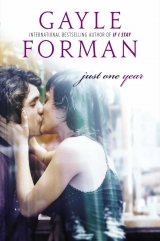

Текст книги "Just One Year"

Автор книги: Gayle Forman

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

Six

Two days later, one hundred thousand euros appears in my bank account, as if by magic. But of course, it’s not magic. It’s been a long time since I was kicked off my economics course, but I’ve since come to understand that the universe operates on the same general equilibrium theory as markets. It never gives you something without making you pay for it somehow.

I buy a beat-up bike off a junkie and another change of clothes from the flea market. I may have money now, but I’ve grown used to living simply, to owning only what I can carry. And besides, I’m not staying long, so I may as well leave as few fingerprints as possible.

I wander up and down the Damrak looking at travel agencies, trying to decide where to go next: Palau. Tonga. Brazil. Once the options increase, settling on one becomes harder. Maybe I’ll track down Uncle Daniel in Bangkok, or is it Bali now?

At one of the student agencies, a dark-haired girl behind the desk sees me peering at the ads. She catches my eye, smiles, and gestures for me to come inside.

“What are you looking for?” she asks in slightly accented Dutch. She sounds Eastern, maybe Romanian.

“Somewhere that isn’t here.”

“Can you be more specific?” she says, laughing a little.

“Somewhere warm, cheap, and far away.” Somewhere that with one hundred thousand euros, I can stay lost as long as I want to, I think.

She laughs. “That describes about half the world. Let’s narrow it down. Do you want beaches? There are some fantastic spots in Micronesia. Thailand is still quite cheap. If you’re into a more chaotic cultural affair, India is fascinating.”

I shake my head. “Not India.”

“New Zealand? Australia? People are raving about Malawi in Central Africa. I’m hearing great things about Panama and Honduras, though they had that coup there. How long do you want to go for?”

“Indefinitely.”

“Oh, then you might look into a round-the-world ticket. We have a few on special.” She types away on her computer. “Here’s one: Amsterdam, Nairobi, Dubai, Delhi, Singapore, Sydney, Los Angeles, Amsterdam.”

“You have one that doesn’t stop in Delhi?”

“You really don’t want India, huh?”

I just smile.

“Okay. So what part of the world doyou want to see?”

“I don’t care. Anywhere will work, really, so long as it’s warm, cheap, and far away. And not India. Why don’t you pick for me?”

She laughs, like it’s a joke. But I’m serious. I’ve been stuck in a kind of sluggish inertia since coming back, spending whole days in sad hostel beds waiting for my meeting with Marjolein. Whole days, lots of empty hours, holding a broken-but-still-ticking watch, wondering useless things about the girl whom it belongs to. It’s all doing a bit of a number on my head. All the more reason for me to get back on the road.

She taps her fingers against her keyboard. “You have to help me out. For starters, where have you already been?”

“Here.” I push my battered passport across the desk. “This has my history.”

She opens it. “Oh it does, does it?” she says. Her voice has changed, from friendly to coy. She flips through the pages. “You get around, don’t you?”

I’m tired. I don’t want to do this dance, not right now. I just want to buy my airplane ticket and go. Once I’m out of here, away from Europe, somewhere warm and far, I’ll get back to my old self.

She shrugs and returns to leafing through my passport. “Uh-oh. You know what? I can’t book you anywhere yet.”

“Why not?”

“Your passport’s about to expire.” She closes the passport and slides it back. “Do you have an identity card?”

“It got stolen.”

“Did you file a report?”

I shake my head. Never did call the French police.

“Never mind. You need a passport for most of these places anyhow. You just have to get it renewed.”

“How long will that take?”

“Not long. A few weeks. Go to City Hall for the forms.” She rattles off some of the other paperwork I’ll need, none of which I have here.

Suddenly I feel stuck, and I’m not sure how that happened. After managing for two entire years not to set foot in Holland? After going to some absurd lengths to bypass this small-but-central landmass—for instance convincing Tor, Guerrilla Will’s dictatorial director, to forgo performing in Amsterdam and to hit Stockholm instead, with some half-baked story about the Swedes being the most Shakespeare-loving people in Europe outside the UK?

But then last spring Marjolein had finally cleared up Bram’s messy estate and the deed of the houseboat transferred to Yael. Who celebrated by immediately putting the home he’d built for her up for sale. I shouldn’t have been surprised, not at that point.

Still, to ask me to come and sign the papers? That took gall. Chutzpah, Saba would call it. I understood for Yael it was a matter of practicality. I was a train ride, she was a plane ride. It would only be a few days for me, a minor inconvenience.

Except I delayed for one day. And somehow, that’s changed everything.

Seven

OCTOBER

Utrecht

It occurs to me, belatedly, that maybe I should’ve called. Maybe last month, when I first got back. Certainly before now, before showing up at his house. But I didn’t. And now it’s too late. I’m just here. Hoping to make this as painless as possible.

At the house on Bloemstraat, someone has swapped out the old doorbell for one in the shape of an eyeball that stares reproachfully. This feels like a bad omen. Our correspondence, always irregular, has been nonexistent in the last few months. I can’t remember the last time I emailed or texted him. Three months ago? Six months? It occurs to me, also belatedly, that he might not even live here anymore.

Except, somehow, I know he does. Because Broodje wouldn’t have left without telling me. He wouldn’t have done that.

Broodje and I met when we were eight. I caught him spying on our boat with a pair of binoculars. When I asked what he was doing, he explained that he wasn’t spying on us. There’d been a rash of break-ins in our neighborhood, and his parents had been talking about leaving Amsterdam for somewhere safer. He preferred to stay put in his family’s flat, so it was up to him to find the culprits. “That’s very serious,” I’d told him. “Yes, it is,” he’d replied. “But I have this.” Out of his bike basket he’d pulled the rest of his spy kit: decoder scope, noise-enhancing ear buds, night-vision goggles, which he’d let me try on. “If you need help finding the bad guys, I can be your partner,” I’d offered. There were not many children in our neighborhood on the eastern edge of Amsterdam’s center, no children at all on the adjacent houseboats on the Nieuwe Prinsengracht where our boat was moored, and I had no siblings. I spent much of my time kicking balls off the pier against the hull of the boat, losing most of them to the murky waters of the canals.

Broodje accepted my help, and we became partners. We spent hours casing the neighborhood, taking pictures of suspicious-looking people and vehicles, cracking the case. Until an old man saw us, and, thinking we were working with the criminals, called the police on us. The police found us crouched next to my neighbor’s pier, looking through the binoculars at a suspicious van that seemed to appear regularly (because, we later found out, it belonged to the bakery around the corner). We were questioned and we both started crying, thinking we were going to jail. We stammered our explanations and crime-fighting strategies. The police listened, trying hard not to laugh, before taking us home and explaining everything to Broodje’s parents. Before they left, one of the detectives gave each of us a card, winked, and said to call with any tips.

I threw away my card, but Broodje kept his. For years. I spotted it when we were twelve, tacked to the bulletin board in his bedroom in the suburbs where he wound up moving after all. “You still have this?” I’d asked him. He’d moved two years before and we didn’t see each other frequently. Broodje had looked at the card, and then looked at me. “Don’t you know, Willy?” he’d said. “I keep things.”

• • •

A lanky guy in a PSV soccer jersey, his hair stiff with gel, opens the door. I feel my stomach plummet, because Broodje used to live here with two girls, both of whom he was constantly, and unsuccessfully, trying to sleep with, and a skinny guy named Ivo. But then the guy eyes spark open with recognition and I realize it’s Henk, one of Broodje’s friends from the University of Utrecht. “Is that you, Willem?” he asks, and before I can answer he’s calling into the house, “Broodje, Willem’s back.”

I hear scrambling and the creak of the scuffed wood floorboards and then there he is, a head shorter and a shoulder wider than me, a disparity that used to prompt the old man on the houseboat next to ours to call us Spaghetti and Meatball, a moniker Broodje quite liked, because wasn’t a meatball so much tastier than a noodle?

“Willy?” Broodje pauses for a half second before he launches himself at me. “Willy! I thought you were dead!”

“Back from the dead,” I say.

“Really?” His eyes are so round and so blue, like shiny coins. “When did you get back? How long are you here for? Are you hungry? I wish you’d told me you were coming, I would’ve made something. Well I can pull together a nice borrelhapje. Come in. Henk, look, Willy’s back.”

“I see that,” Henk says, nodding.

“W,” Broodje calls. “Willy’s back.”

I walk into the lounge. Before, it was relatively neat, with feminine touches around like flower-scented candles that Broodje used to pretend to dislike but would light even when the girls weren’t home. Now, it smells of stale socks, old coffee, and spilled beer, and the only remnant of the girls is an old Picasso poster, askew in its frame above the mantel. “What happened to the girls?” I ask.

Broodje grins. “Leave it to Willy to ask about the girls first.” He laughs. “They moved into their own flat last year, and Henk and W moved in. Ivo just left to do a course in Estonia.”

“Latvia,” Wouter, or W, corrects, coming down the stairs. He’s even taller than me, with short, unintentionally spiky hair and an Adam’s apple as big as a doorknob.

“Latvia,” Broodje says.

“What happened to your face?” W asks. W never was one for social pleasantries.

I touch the scar. “I fell off my bike,” I say. The lie I told Marjolein comes out automatically. I’m not sure why, except for a desire to put as much distance as possible between myself and that day.

“When did you get back?” W asks.

“Yeah, Willy,” Broodje says, panting and pawing like a puppy. “How long ago?”

“A bit ago,” I say, treading water between hurtful truth and balls-out lies. “I had to deal with some things in Amsterdam.”

“I’ve been wondering where you were,” Broodje says. “I tried calling you a while back but got a strange recording, and you’re shit about email.”

“I know. I lost my phone and all my contacts, and some Irish guy gave me his, including his SIM card. I thought I texted you the new number.”

“Maybe you did. Anyhow, come in. Let me go see what I have to eat.” He turns right into the galley kitchen. I hear drawers opening and closing.

Five minutes later Broodje returns with a tray of food and beers for all of us. “So tell us everything. The glamorous life of a roving actor. Is it a girl every night?”

“Jesus, Broodje, let the guy sit down,” Henk says.

“Sorry. I live vicariously through him; it was like having a movie star in the house having him around. And, it’s been a little dry these past few years.”

“And by past few years, you mean twenty?” W says drolly.

“So you’ve been in Amsterdam?” Broodje asks. “How is your ma?”

“I wouldn’t know,” I say lightly. “She’s in India.”

“Still?” Broodje asks. “Or there and back?”

“Still. This whole time.”

“Oh. I was in the old neighborhood recently and the boat was all lit up and there was furniture inside, so I thought she might be back.”

“Nope, they must’ve put furniture in there to make it look lived in, but it’s not. Not by us, anyhow,” I say, rolling up a piece of cervelaatand shoving it in my mouth. “It’s been sold.”

“You sold Bram’s boat?” Broodje says incredulously.

“My mother sold it,” I clarify.

“She must’ve made a boatload,” Henk jokes.

I pause for a second, somehow unable to tell them that I did, too. Then W starts talking about a piece he read in De Volkskrantrecently about Europeans paying top dollar for the old houseboats in Amsterdam, for the mooring rights, which are as valuable as the boats themselves.

“Not this boat. You should’ve seen it,” Broodje says. “His father was an architect, so it was beautiful, three floors, balconies, glass everywhere.” He looks wistful. “What did that magazine call it?”

“Bauhaus on the Gracht.” A photographer had come and taken pictures of the boat, and us on it. When the magazine had come out, most of the shots had been of just the boat, but there had been one of Yael and Bram, framed by the picture window, the trees and canal reflecting like a mirror behind them. I’d been in the original of that shot but had been cropped out. Bram explained that they’d used this one because of the window and the reflection; it was a representation of the design, not our family. But I’d thought it had been a fairly accurate depiction of our family, too.

“I can’t believe she sold it,” Broodje says.

Some days I can’t believe it and other days I can absolutely believe it. Yael is the sort to chew off her own hand if she needs to escape. She’d done it before.

The boys are all looking at me now, their faces blanking out with a kind of concern that I’m unaccustomed to after two years of anonymity.

“So, Holland-Turkey tonight,” I begin.

The guys look at me for a moment. Then nod.

“I hope things go better for us,” I say. “After the sad offerings during Euro Cup, I don’t know if I can take it. Sneijder . . .” I shake my head.

Henk takes the bait first. “Are you kidding? Sneijder was the only striker who proved his mettle.”

“No way!” Broodje interrupts. “Van Persie scored that beautiful goal against Germany.”

Then W jumps in with math talk, something about regression toward the mean guaranteeing improvement after the last lousy year, and now there’s nowhere to go but up, and I relax. There’s a universal language of small talk. On the road, it’s about travel: some unknown island, or a cheap hostel, a restaurant with a good fixed-price menu. With these guys, it’s soccer.

“You gonna watch the game with us, Willy?” Broodje asks. “We were going to O’Leary’s.”

I didn’t come to Utrecht for small talk or for soccer or for friendship. I came for paperwork. A quick visit to University College for some papers to get my passport. Once I get that, I’ll go back to the travel agent, maybe ask her for a drink this time, and figure out where to go. Buy my ticket. Maybe take a trip to The Hague to pick up some visas, a visit to the travel clinic for some shots. A trip to the flea market for new clothes. A train to the airport. A thorough body search by immigration officials, because a lone man with a one-way ticket is always an object of suspicion. A long flight. Jetlag. Immigration. Customs. And then finally, that first step into a new place, that moment of exhilaration and disorientation, each feeding the other. That moment when anything can happen.

I have only one thing to do in Utrecht, but suddenly the rest of the things I’ll need to accomplish to get myself out of here feels endless. Stranger yet, nothing about it excites me. Not even arriving somewhere new, which used to make all the hassle worthwhile. It all just seems exhausting. I can’t summon the energy for the slog it’ll take me to get out of here.

But O’Leary’s? O’Leary’s is right around the corner, not even a block away. That I can manage.

Eight

October turns cold and wet, as if we used up our quota of clear, hot days during the summer’s heat wave. It’s especially cold in my attic room on Bloemstraat, making me wonder if moving in had been the right call. Not that it had been a call. After I woke up on the downstairs sofa for the third morning in a row, having accomplished little during my days in Utrecht, Broodje had suggested I move into the attic room.

The offer was wasn’t so much enticing as a fait accompli. I was already living here. Sometimes the wind blows you places you weren’t expecting; sometimes it blows you away from those places, too.

• • •

The attic room is drafty, with windows that rattle in the wind. In the morning, I see my breath. Staying warm becomes my main vocation. On the road, I often spent whole days in libraries. You could always find magazines or books, and respite from the weather or whatever else needed escaping.

The Central University library offers all the same comforts: big sunny windows, comfortable couches, and a bank of computers I can use to browse the Internet. The last is a mixed blessing. On the road, my fellow travelers were obsessive about keeping up with email. I was the opposite. I hated checking in. I still do.

Yael’s emails come like clockwork, once every two weeks. I think she must have it on her calendar, along with all the other chores. The notes never say much, which makes answering them next to impossible.

One came yesterday, a bit of fluff about taking a day off to go to a pilgrim festival in some village. She never tells me what she’s taking a day off from, never elaborates about her actual work there, her day-to-day life, which is a bleary mystery, the contours filled in only by offhanded remarks from Marjolein. No, Yael’s emails to me are all in a sort of postcard language. The perfect small talk, saying little, revealing less.

“Hoi Ma,” I begin my reply. And then I stare at screen and try to think of what to say. I’m so conversant in every kind of small talk, but I find myself at a loss for words when it comes to my mother. When I was traveling, it was simpler because I could just send a sort of postcard. In Romania now at one of the Black Sea resorts, but it’s off season and quiet. Watched the fishermen for hours. Although even those had addendums in my mind. How watching the fishermen one blustery morning reminded me of our family trip to Croatia when I was ten. Or was it eleven? Yael slept late, but Bram and I woke early to go down to the docks to buy the day’s catches from the just-returning fisherman, who all smelled of salt and vodka. But following Yael’s lead, I excise those bits of nostalgia from my missives.

“Hoi Ma.” The cursor blinks like a reprimand and I can’t get past it, can’t think of what to say. I toggle back to my inbox, scrolling backward in time. The last few years and their occasional notes from Broodje, and the notes from people I met on the road—vague promises to meet up in Tangiers, in Belfast, in Barcelona, in Riga—plans that rarely materialized. Before that, there’s the flurry of emails from various professors on the economics faculty, warning me that unless I appealed “special circumstances,” I was in danger of not being asked back next year. (I didn’t, and I wasn’t.) Before that, condolence emails, some of them still unopened, and before that, notes from Bram, mostly silly things he liked to forward to me, a restaurant review of a place he wanted to try out, a photo of a particularly monstrous piece of architecture, an invitation to help on his latest fix-it project. I scroll back now four years and there are the emails from Saba, who, in the two years between discovering email and getting too sick to use it, had delighted in this instant form of communication, where you could write pages and pages and it didn’t cost any more to send.

I return to the note to Yael. “Hoi Ma, I’m back in Utrecht now, hanging out with Robert-Jan and the boys. Nothing much to report. It’s pissing down rain every day; no sign of the sun for a week now. You’re glad not to be here for it. I know how you hate the gray. Talk soon. Willem.”

Postcard Language, the smallest of small talk.

Nine

The boys and I are going to a movie, along with W’s new girlfriend. Some Jan de Bont thriller at the Louis Hartlooper. I haven’t liked a de Bont film since—I can’t even remember—but I’ve been outvoted because W has a girlfriend, and this is a big thing, and if she wants explosions, we will watch explosions.

The theater complex is packed, people spilling out the front doors. We fight our way through the crowds to the box office. And that’s when I see her: Lulu.

Not my Lulu. But the Lulu I named her for. Louise Brooks. The theater has lots of old movie posters in the lobby, but I’ve never seen this one, which isn’t on the wall but is propped up on an easel. It’s a still shot from Pandora’s Box, Lulu, pouring a drink, her eyebrow raised in amusement and challenge.

“She’s pretty.” I look up. Behind me is Lien, W’s punked-out math major girlfriend. No one can quite get over how he did it, but apparently they fell in love over numbers theory.

“Yeah,” I agree.

I look closer at the poster. It is advertising a Louise Brooks film retrospective. Pandora’s Boxis on tonight.

“Who was she?” Lien asks.

“Louise Brooks,” Saba had said. “Look at those eyes, so much delight, you know there’s sadness to hide.” I was thirteen, and Saba, who hated Amsterdam’s mercurial wet summers, had just discovered the revival cinemas. That summer was particularly dreary, and Saba had introduced me to all the silent film stars: Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Rudolph Valentino, Pola Negri, Greta Garbo, and his favorite, Louise Brooks.

“Silent film star,” I tell Lien. “There’s a festival on. Unfortunately it’s tonight.”

“We could see that instead,” she says. I can’t tell if her tone is sarcastic; she’s as dry as W is. But when I get to the front of the line to buy the tickets, I find myself asking for five to Pandora’s Box.

At first, the boys are amused. They think I’m joking, until I point to the poster and explain about the retrospective. Then they are not so amused.

“There’s a live piano player,” I say.

“Is that supposed to make us feel better?” Henk asks.

“No way I’m seeing this,” W adds.

“What if Iwanted to see it?” Lien interjects.

I offer her a silent thank-you and she gives me a perplexed eyebrow raise in return, showing off her piercing. W acquiesces and the rest follow suit.

Upstairs, we take our seats. In the quiet, you can hear the explosions from the adjacent theater and I can see Henk’s eyes go wistful.

The lights go down and the piano player starts in with the overture and Lulu’s face fills the screen. The movie starts, all scratchy and black and white; you can almost hear it crackle like an old LP. But there is nothing old about Lulu. She’s timeless, flirting gaily in the nightclub, being caught with her lover, shooting her husband on their wedding night.

It’s strange because I’ve seen this film before, a few times. I know exactly how it ends, but as it goes on, a tension starts to build, a suspense, churning uncomfortably in my gut. It takes a certain kind of naiveté, or perhaps just stupidity, to know how things will end and still hope otherwise.

Fidgety, I shove my hands into my pockets. Though I try not to, my mind keeps going to the other Lulu on that hot August night. I tossed her the coin, as I’d done to so many other girls. But unlike the other girls who always came back—lingering by our makeshift stage to return my very valuable worthless coin and to see what it might buy—Lulu didn’t.

That should’ve been my first sign that the girl could see through my acts. But all I’d thought was: Not to be. It was just as well. I had an early train to catch the next day, and a big, shitty day after that, and I never slept well with strangers.

I hadn’t slept well anyhow, and I’d been up early, so I’d caught an earlier train down to London. And there she was, on that train. It was the third time in twenty-four hours that I’d seen her and when I walked into that train’s café car, I remember feeling a jolt. As if the universe was saying: pay attention.

So I’d paid attention. I’d stopped and we’d chatted, but then we were in London and about to go our separate ways. By that point, the knot of dread that had been building in me since Yael’s request that I return to Holland to sign away my home had solidified into a fist. The banter with Lulu on the way down to London had made it unravel, somehow. But I knew that once I got on that next train to Amsterdam, it would grow, it would take over my insides, and I wouldn’t be able to eat or do anything except nervously roll a coin along my knuckles and focus on the next next—the next train or plane I’d be boarding. The next departure.

But then Lulu started talking about wanting to go to Paris, and I had all this money from the summer’s worth of Guerrilla Will, cash I wouldn’t be needing much longer. And in that train station in London, I’d thought, okay, maybe thiswas the meant to be: The universe, I knew, loved nothing more than balance, and here was a girl who wanted to go to Paris and here was me who wanted to go anywhere but back to Amsterdam. As soon as I’d suggested we go to Paris together, balance was restored. The dread in my gut disappeared. On the train to Paris, I was as hungry as ever.

On screen, Lulu is crying. I imagine my Lulu waking up the next day, finding me gone, reading a note that promised a quick return that never materialized. I wonder, as I have so many times, how long it took her to think the worst of me when she already hadthought the worst of me. On the train from London to Paris, she’d started laughing uncontrollably, because she’d thought I’d left her there. I’d made a joke of it; and of course, it wasn’t true. I wasn’t planning that. But it had got to me because it was my first warning that somehow, this girl saw me in a way I hadn’t intended to be seen.

As the movie goes on, desire and longing and regret and second-guessing of everything about that day start building in me. It’s all pointless, but somehow knowing that only makes it worse, and it builds and builds and has nowhere to go. I shove my hands deeper into my pockets and punch a hole right through.

“Damn!” I say, louder than I mean to.

Lien looks at me, but I pretend to be absorbed in the movie. The piano player is building to a crescendo as Lulu flirts with Jack the Ripper and, lonely and defeated, invites him up to her room. She thinks she has found someone to love, and he thinks that he has found someone to love, and then he sees the knife, and you know what will happen. He’ll just revert to his old ways. I’m sure that’s what she thinks of me, and maybe she’s right to think it. The film ends with a frenzied flourish of the piano. And then there’s silence.

The boys sit there for a minute and then all start talking at once. “That’s it? So he killed her?” Broodje asks.

“It’s Jack the Ripper and he had a knife,” Lien responds. “He wasn’t carving her a Christmas turkey.”

“What a way to go. I’ll give you one thing, it wasn’t boring,” Henk says. “Willem? Hey, Willem, are you there?”

I startle up. “Yeah. What?”

The four of them all look at me for what feels like a while. “Are you okay?” Lien asks at last.

“I’m fine. I’m great!” I smile. It feels unnatural I can almost feel the scar on my face tug like a rubber band. “Let’s go get a drink.”

We all make our way to the crowded café downstairs. I order a round of beers and then a round of jeneverfor good measure. The boys give me a look, though if it’s for the booze or for paying for it all, I don’t know. They know about my inheritance now, but they still expect the same frugality from me as always.

I drain my shot and then my beer.

“Whoa,” W says, passing me his shot. “No kopstootfor me.”

I knock his shot back, too.

They’re quiet as they look at me. “Are you sure you’re okay?” Broodje asks, strangely hesitant.

“Why wouldn’t I be?” The jeneveris doing its job, heating me up and burning away the memories that came alive in the dark.

“Your father died. Your mother left for India,” W says bluntly. “Also, your grandfather died.”

There’s a moment of awkward silence. “Thanks,” I say. “I’d forgotten all about that.” I mean it to come out as a joke, but it just comes out as bitter as the booze that’s burning its way back up my throat.

“Oh, don’t mind him,” Lien says, tweaking his ear affectionately. “He’s working on human emotions like sympathy.”

“I don’t need anyone’s sympathy,” I say. “I’m fine.”

“Okay, it’s just you haven’t really seemed yourself since . . .” Broodje trails off.

“You spend a lot of time alone,” Henk blurts.

“Alone? I’m with you.”

“Exactly,” Broodje says.

There’s another moment of silence. I’m not quite sure what I’m being accused of. Then Lien illuminates.

“From what I understand, you always had a girl around, and now the guys are worried because you’re always alone,” Lien says. She looks at the boys. “Do I have that right?”

Kind of sort of yeah, they all mumble.

“So you’ve been discussing this?” This should be funny, except it’s not.

“We think you’re depressed because you’re not having sex,” W says. Lien smacks him. “What?” he asks. “It’s a viable physiological issue. Sexual activity releases serotonin, which increases feelings of well-being. It’s simple science.”

“No wonder you like me so much,” Lien teases. “All that simple science.”

“Oh, so I’m depressed now?” I try to sound amused but it’s hard to keep that tinge of something else out of my voice. No one will look at me except for Lien. “Is that what you think?” I ask, trying to make a joke of it. “I’m suffering from a clinical case of blue balls?”

“It’s not your balls I think are blue,” she says coolly. “It’s your heart.”

There’s a beat of silence, and then the boys erupt into raucous laughter. “Sorry, schatje,” W says. “But that would be anomalous behavior. You just don’t know him yet. It’s much more likely a serotonin issue.”

“I know what I know,” Lien says.

They all argue over this and I find myself wishing for the anonymity of the road, where you had no past and no future either, just that one moment in time. And if that moment happened to get sticky or uncomfortable, there was always a train departing to the next moment.

“Well, if he does have a broken heart or blue balls, the cure is the same,” Broodje says.