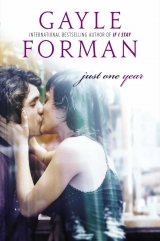

Текст книги "Just One Year"

Автор книги: Gayle Forman

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

Forty-three

So much to do. There’s an all-cast rehearsal at noon. Then a tech run-through. I need to run back to the flat, grab some things, tell the boys. And Daniel. Yael.

Broodje is only waking up. Breathlessly, I tell him the news. By the time I’ve finished, he’s already on his phone, calling the boys.

“Did you tell your ma?” he asks when he hangs up.

“I’m calling her now.”

I calculate the time difference. It’s not quite five o’clock in Mumbai, so Yael will still be working. I send her an email instead. While I’m at it, I send one to Daniel. At the last minute, I send one to Kate, telling her about Jeroen’s accident, inviting her to tonight’s show if she’s at all in the area. I even invite her to stay with me and give her the address of the flat.

I’m about to log off when I do a quick scan of my inbox. There’s a new message from an unfamiliar address and I think it’s junk. Until I see the subject line: Letter.

My hand’s shaking a bit as I click on the message. It’s from Tor. Or relayed from Tor via some Guerrilla Will player who doesn’t abide by the email ban as she does.

Hi Willem:

Tor asked me to email you to say that she ran into Bex last week and Bex told her that you hadn’t gotten that letter. Tor was pretty upset because the letter was important and she’d gone to a lot of trouble to try to get it to you. She wanted you to know it was from a girl you’d met in Paris who was looking for you because you’d dicked her over and pulled a runner. (Tor’s words, not mine.) She said that you ought to know that actions have consequences. Again, Tor’s words. Don’t shoot the messenger.

Cheers! Josie

I sink down onto my bed as very different emotions battle it out. Dicked her over, pulled a runner. I feel Tor’s anger. And Lulu’s too. Shame and regret well up but then just stop there, held at bay by some invisible force. Because she’s looking for me. Lulu is looking for me, too. Or she was. Maybe just to tell me to piss off. But she was looking for me like I was looking for her.

I don’t know what to feel as I wander into the kitchen. It’s all just too much for one day.

I find Broodje cracking eggs into a frying pan. “Want an uitsmijter?” he asks.

I shake my head.

“You should eat something. Keep your strength up.”

“I have to go.”

“Now? Henk and W are on their way over. They want to see you. Will you be around at all before your big debut?”

The rehearsal starts at noon and will take at least three hours, and then Linus said I’d have a break before I go for a run-through at the amphitheater at six. “I can probably get back here around four or five?”

“Great. We should have the party plans well under way by then.”

“Party plans?”

“Willy, this is big.” He pauses to look at me. “After the year you’ve had—the yearsyou’ve had—we should celebrate this.”

“Okay, fine,” I say, still half dazed.

I go back into my room to pack up a change of clothes for under the costume, shoes to wear. I’m about to leave when I see Lulu’s watch sitting on my shelf. I hold it in my hand. After all this time, it’s still ticking. I hold it in my hand a moment longer. Then I slip it into my pocket.

Forty-four

At the theater, the rest of the cast has assembled. Max comes up behind me. “ I’ve got your back,” she whispers.

I’m about to ask her what she means, and then I see what she means. For the better part of three months, I have been mostly invisible to many of these people, a shadow-cast member. And now, the spotlight is glaring and there’s no safety in the shadows anymore. People are looking at me with a particular mix of suspicion and condescension, a familiar feeling from when I was traveling and walked through certain neighborhoods where my kind didn’t tend to wander. As I did when I was traveling, I just act like I don’t notice and carry on. Soon enough Petra is clapping her hands, gathering us together.

“We have no time to lose,” Linus says. “We will do a modified run-through, skipping over scenes that Orlando is not in.”

“So why did you call allof us in?” mutters Geert, who plays the swing roles of one of Frederick’s men and Silvius; he has almost no scenes with Orlando.

“I know. Sitting around watching other people act is such a bloody waste of time,” Max says, her voice so sincere that it takes Geert a few seconds to have the good sense to look chastened.

Max gives me a crooked smile. I’m glad she’s here.

“I called everyone in,” Petra says, with an exaggerated patience that lets you know she’s reaching the end of her supply, “so you could all accustom yourself to the different rhythms of a new actor, and so we could all of us help Willem ensure that the transition between him and Jeroen is as seamless as possible. Ideally, you won’t even be able to tell the difference.”

Max rolls her eyes at this and once again I’m glad she’s here.

“Now from the top, please,” Linus says, tapping his clipboard. “There’s no set and no marks so just do your best.”

As soon as I step onto the stage, I feel relieved. This is where I’m meant to be. In Orlando’s head. As we move through the play, I discover more things about Orlando. I discover how key that first scene when he and Rosalind meet is. It’s just for a few moments, but they see something in each other, recognize something. And that the spark sustains the passion, for both of them, for the rest of the play. They don’t see each other—knowingly see each other—again until the very end.

Such a dance that Shakespeare wrote into a handful of pages of text. Orlando’s about to fight a man far stronger than he is, but he peacocks in front of Rosalind and Celia to impress them. He’s scared, he must be, but instead of showing it, he bluffs. He flirts. “Let your fair eyes and gentle wishes go with me to my trial,” he says.

The world pivots on moments. And in this play, it’s the moment when Rosalind says, “The little strength that I have, I would it were with you.”

That one line. It cracks open his facade. It reveals what’s underneath. Rosalind sees Orlando. He sees her. That’s the whole play, right there.

I feel the lines like I haven’t before, like I’m truly understanding Shakespeare’s intentions. I feel as if there really was a Rosalind and an Orlando and I’m here to represent them. It isn’t acting in a play. It goes back further than that. It’s much bigger than me.

“Ten-minute break,” Linus calls at the end of Act One. Everyone heads out for a smoke or a coffee. But I am reluctant to leave the stage.

“Willem,” Petra calls to me. “A word.”

She’s smiling, which she rarely does, and at first I read it for pleasure, because isn’t that what a smile communicates?

The theater empties out. It’s just the two of us now. Not even Linus. “I want to tell you how impressed I am,” she begins.

Inside I’m a little boy grinning on a birthday morning, about to get the presents. But I try to keep my face professional.

“With so little experience, to know the language so well. We were taken with your ease with the language at your audition, but this . . .” She smiles again, only now I notice that it looks a bit like a dog baring its fangs. “And the blocking, you have it cold. Linus tells me that you even learned some of the fight choreography.”

“I observed,” I tell her. “I paid attention.”

“Excellent. That’s just what you needed to do.” And there’s that smile again. Only now do I begin to doubt it reflects any pleasure. “I spoke to Jeroen today,” she continues.

I don’t say anything but my gut twists. All this, and now Jeroen is going to lumber back with his cast.

“He’s terribly embarrassed by what happened, but most of all he’s disappointed to have let down his company.”

“There’s no one to blame. He was in an accident,” I say.

“Yes. Of course. An accident. And he very much wants to be back for the last two weeks of the season and we will do our best to adapt to meet his needs, because that is what you do when you are part of a cast. Do you understand?”

I nod, even though I don’t really understand what she’s on about.

“I understand what you were trying to do up there with your Orlando.”

Your Orlando. Something about the way she says that makes me feel like it won’t be mine for much longer.

“But the role of the understudy is not to bring his own interpretation to the part,” she continues. “It is to play the part as the actor you’re replacing played it. So in effect, you aren’t playing Orlando. You are playing Jeroen Gosslers playing Orlando.”

But Jeroen’s Orlando is all wrong, I want to say. It’s all machismo and prancing and no revealing; and without vulnerability, Rosalind wouldn’t love him, and if Rosalind doesn’t love him, why should the audience care? I want to say: Let me do this. Let me do it right this time.

But I don’t say any of that. And Petra just stares at me. Then, finally she asks: “Do you think you can manage that?”

Petra smiles again. How foolish of me—of all people—not to recognize her smile for what it was. “We can still cancel for this weekend,” she says, her voice soft, the threat clear. “Our star has had an accident. No one would fault us.”

Something given, something taken away. Does it always have to work like that?

The cast starts to drift back into the theater, the ten-minute break over, ready to get back to work, to make this happen. When they see me and Petra talking, they go quiet.

“Are we understood?” she asks, her voice so friendly it’s almost singsong.

I look at the cast again. I look at Petra. I nod. We’re understood.

Forty-five

When Linus releases us for the afternoon, I bolt for the door. “Willem,” Max calls.

“Willem,” Marina calls behind her.

I wave them off. I have to be fitted for my costume and then I have only a couple hours until Linus will meet me to go through my marks on the amphitheater stage. As for what Marina and Max have to say: if it’s compliments of my performance, so Jeroen-like even Petra was impressed, I don’t want to hear it. If it’s questions about why I’m playing it like this, when I played it so differently before, then I really don’t want to hear it.

“I have to go,” I tell them. “I’ll see you tonight.”

They look wounded, each in their own way. But I just walk away from them.

Back at the flat, I find W, Henk, and Broodje busy at work, pages of yellow pad on the coffee table. “That’s Femke in,” Broodje is saying. “Hey, it’s the star.”

Henk and W start to congratulate me. I just shake my head. “What’s all this?” I gesture to the project on the table.

“Your party,” W says.

“My party?”

“The one we’re throwing tonight,” Broodje says.

I sigh. I forgot all about that. “I don’t want a party.”

“What do you mean you don’t want a party?” Broodje asks. “You said it was okay.”

“Now it’s not. Cancel it.”

“Why? Aren’t you going on?”

“I’m going on.” I go into my room. “No party,” I call.

“Willy,” Broodje yells after me.

I slam the door, lie down on the bed. I close my eyes and try to sleep, but that’s not happening. I sit up and flip through one of Broodje’s copies of Voetbal Internationalbut that’s not happening either. I toss it back on my bookshelf. It lands next to a large manila envelope. The package of photos I unearthed from the attic last month.

I open the envelope, thumb through the pictures. I linger on the one of me and Yael and Bram from my eighteenth birthday. It’s like an ache, how much I miss them. How much I miss her. I’m so tired of missing things I don’t have.

I pick up the phone, not even calculating the time difference.

She answers straight away. And just like that time before, I’m at a loss for words. But not Yael. Not this time.

“What’s wrong? Tell me.”

“Did you get my email?”

“I haven’t checked it. Is something wrong?”

She sounds panicked. I should know better. Out-of-the-blue phone calls. They require reassurance. “It’s nothing like that.”

“Nothing like what?”

“Like before. I mean, nobody is sick, though someone did break an ankle.” I tell her about Jeroen, about my taking on his part.

“But shouldn’t this make you happy?” she asks.

I thought it would make me happy. It did make me so happy this morning. Hearing about Lulu’s letter made me happy this morning. But now that’s worn off and all I feel is her recrimination. How far the pendulum can swing in one day. You’d think I’d know that by now. “It appears not.”

She sighs. “But Daniel said you seemed so energized.”

“You spoke to Daniel? About me?”

“Several times. I asked his advice.”

“You asked Danielfor advice?” Somehow this is even more shocking than her asking him about me.

“I wondered if he thought I should ask you to come back here.” She pauses. “To live with me.”

“You want me to come back to India?”

“If you want to. You might act here. It seemed to go well for you. And we could find a bigger flat. Something big enough for both of us. But Daniel thought I should hold off. He thought you seemed to have found something.”

“I haven’t found anything. And you might’ve asked me.” It comes out so bitter.

She must hear it, too. But her voice stays soft. “I amasking you, Willem.”

And I realize she is. After all this time. Tears well up in my eyes. I’m grateful, in that small moment, for the thousands of kilometers that separate us.

“How soon could I come?” I ask.

There’s a pause. Then she gives the answer I need: “As soon as you want.”

The play. I’ll have to do it this weekend, and then Jeroen will come back or I can quit. “Monday?”

“Monday?” She sounds only a little bit surprised. “I’ll have to ask Mukesh what he can do.”

Monday. It’s in three days. But what is there to stay for? The flat is finished. Soon enough Daniel and Fabiola will be back with the baby, and there won’t be room for me.

“It’s not too soon?” I ask.

“It’s not too soon,” she says. “I’m just grateful it’s not too late.”

There’s a hitch in my throat and I can’t speak. But I don’t need to. Because Yael starts speaking. In torrents, apologizing for keeping me at arm’s length, telling me what Bram always said, that it wasn’t me, it was her, Saba, her childhood. All the things I already knew but just didn’t really understand until now.

“Ma, it’s okay.” I stop her.

“It’s not, though,” she says.

But it is. Because I understand all the ways of trying to escape, how sometimes you escape one prison only to find you’ve built yourself a different one.

It’s a funny thing, because I think that my mother and I may finally be speaking the same language. But somehow, now words don’t seem as necessary.

Forty-six

Ihang up the phone with Yael, feeling as though someone has opened a window and let the air in. This is how it is with traveling. One day, it all seems hopeless, lost. And then you take a train or get a phone call, and there’s a whole new map of options opening up. Petra, the play, it had seemed like something, but maybe it was just the latest place the wind blew me. And now it’s blowing back to India. Back to my mother. Where I belong.

I’m still holding the envelope of photos. Once again, I forgot to ask Yael about them. I look at the one of Saba and mystery girl and realize now why she looked familiar to me the first time I saw her. With her dark hair and playful smile and bobbed hair, she looks quite a bit like Louise Brooks, this . . . I grab the newspaper clipping . . . this Olga Szabo. Who was she? Saba’s girlfriend? Was she Saba’s one that got away?

I’m not quite sure what to do with them now. The safest thing would be to put them back in the attic, but that feels a little like imprisoning them. I could make copies of them and take the originals with me, but they still might get lost.

I stare at the picture of Saba. I flip to one of Yael. I think of the impossible life those two had together because Saba loved her so much and tried so hard to keep her safe. I’m not sure it’s possible to simultaneously love something and keep it safe. Loving someone is such an inherently dangerous act. And yet, love, that’s where safety lives.

I wonder if Saba understood this. After all, he’s the one who always said: The truth and its opposite are flip sides of the same coin.

Forty-seven

It’s half past four. I’m not due to meet Linus until six for a quick tech run through before the curtain. Out in the lounge, I hear Broodje and the boys. I don’t want to face them. I can’t imagine telling them I’m going back to India in three days.

I leave my phone on the bed and slip out the door, saying good-bye to the boys. Broodje gives me such a mournful look. “Do you even want us to go tonight?” he asks.

I don’t. Not really. But I can’t be that cruel. Not to him. “Sure,” I lie.

Downstairs, I bump into my neighbor Mrs. Van Der Meer, who’s on her way out to walk her dog. “Looks like we’re getting some sun finally,” she tells me.

“Great,” I say, though this is one time I’d prefer rain. People will stay away in the rain.

But, sure enough, the sun is fighting its way through the stubborn cloud cover. I make my way over to the little park across the street. I’m almost through the gates when I hear someone calling my name. I keep going. There are a thousand Willems. But the name gets louder. And then it yells in English. “Willem, is that you?”

I stop. I turn around. It can’t be.

But it is. Kate.

“Jesus Christ, thank God!” she says, running up to me. “I’ve been calling you and there’s no answer and then I came over but your stupid bell doesn’t work. Why didn’t you pick up?”

It feels like I sent her that email a year ago. From a different world. I’m embarrassed by it now, to have asked her to come all this way. “I left it in the flat.”

“Good thing I saw your dog-walking neighbor and she said she thought you went this way. It’s like one of your little accidents.” She laughs. “It’s a day of them. Because your email came at the most serendipitous moment. David was intent on dragging me to the most hideous sounding avant-garde Medeain Berlin tonight and I was desperately trying to find an excuse not to go, and then this morning I got your email so I came here instead. And I was on the plane when I realized I had no idea where you were performing. And you didn’t answer your phone and I got a little panicky, so I thought I’d track you down. But now here we are and everything’s good.” She exaggeratedly wipes a hand across her brow. “Phew!”

“Phew,” I say weakly.

Kate’s radar goes up. “Or maybe not phew.”

“Perhaps not.”

“What is it?”

“Can I ask you to do something?” I’ve asked Kate so much already. But having her there? Broodje and the boys, they may not know any better. But Kate will. She can see through all the bullshit.

“Of course.”

“Will you not go tonight?”

She laughs. As if this is a joke. And then she realizes it’s not a joke “Oh,” she says, turning serious. “Are they not putting you on? Did the other Orlando’s ankle mysteriously heal?”

I shake my head. I look down and see that Kate is holding her suitcase. She literally did come straight from the airport. To see me.

“Where are you staying?” I ask Kate.

“The only place I could find at the last minute.” She pulls out a slip of paper from her bag. “Major Rug Hotel?” she says. “I have no idea how to pronounce it, let alone where it is.” She hands me the paper. “Do you know it?

Hotel Magere Brug. I know exactly where it is. I rode past it almost every day of my life. On weekends they used to serve homemade pastries in the lobby, and Broodje and I would sneak in sometimes to take some. The manager pretended not to notice.

I take her suitcase. “Come on. I’ll take you home.”

• • •

The last time I was at the boat, it was September; I got as far as the pier before I rode away. It looked so empty, so haunted, like it was mourning his loss, too, which made a certain sense because he built it. Even the clematis that Saba had planted—“because even a cloud-soaked country needs shade”—which had once run riot over the deck, had gone shriveled and brown. If Saba had been here, he would’ve cut it back. It’s what he always did when he came back in the summer and found the plants ailing in his absence.

The clematis is back now, bushy and wild, dropping purple petals all over the deck. The deck is full of other blooms, trellises, vines, arbors, pots, viny flowering things.

“This was my home,” I tell Kate. “It’s where I grew up.”

Kate was mostly quiet on the tram ride over. “It’s beautiful,” she says.

“My father built it.” I can see Bram’s winked smile, hear him announce as if to no one: I need a helper this morning.Yael would hide under the duvet. Ten minutes later, I’d have a drill in my hand. “I helped, though. I haven’t been here in a long time. Your hotel is just around the corner.”

“What a coincidence,” she says.

“Sometimes I think everything is.”

“No. Everything isn’t.” She looks at me. Then she asks, “So what’s wrong, Willem? Stage fright?”

“No.”

“Then what is it?”

I tell her. About getting the call this morning. About that moment in the first rehearsal, finding something new, finding something real in Orlando, and then having it all go to hell.

“Now I just want to get up there, get through it, get it over with,” I tell her. “With as few witnesses as possible.”

I expect sympathy. Or Kate’s undecipherable yet somehow resonant acting advice. Instead, I get laughter. Snorts and hiccups of it. Then she says, “You have got to be kidding me.”

I am not kidding. I don’t say anything.

She attempts to contain herself. “I’m sorry, but the opportunity of a lifetime drops into your lap—you finally get one of your glorious accidents—and you’re going to let a lousy piece of direction derail you.”

She is making it seem so slight, a bad piece of advice. But it feels like so much more. A wallop in the face, not a piece of bad direction, but a redirection. This is not the way. And just when I thought I had really found something. I try to find the words to explain this . . . this betrayal. “It’s like finding the girl of your dreams,” I begin.

“And realizing you never caught her name?” Kate finishes.

“I was going to say finding out she was actually a guy. That you had it so completely wrong.”

“That only happens in movies. Or Shakespeare. Though it’s funny you mention the girl of your dreams, because I’ve been thinking about your girl, the one you were chasing in Mexico.”

“Lulu? What does she have to do with this?”

“I was telling David about you and your story and he asked this ridiculously simple question that I’ve been obsessing about ever since.”

“Yes?”

“It’s about your backpack.”

“You’ve been obsessing about my backpack?” I make it sound like a joke, but all of a sudden, my heart has sped up. Pulled a runner. Dicked her over. I can hear Tor’s disgust, in that Yorkshire accent of hers.

“Here’s the thing: If you were just going out for coffee or croissants or to book a hotel room or whatever, why did you take your backpack, with all your things in it, with you?”

“It wasn’t a big backpack. You saw it. It was the same one I had in Mexico. I always travel light like that.” I’m talking too fast, like someone with something to hide.

“Right. Right. Traveling light. So you can move on. But you were going back to that squat, and you had to climb, if I recall, out of a second-story building. Isn’t that right?” I nod. “And you brought a backpack with you? Wouldn’t it have been easier to leave most of your things there? Easier to climb. At the very least, it would’ve been a sure sign that you intended to return.”

I was there on that ledge, one leg in, one leg out. A gust of wind, so sharp and cold after all that heat, knifed through me. Inside, I heard rustling as Lulu rolled over and wrapped herself in the tarp. I’d watched her for a moment, and as I did, this feeling had come over me stronger than ever. I’d thought, Maybe I should just wait for her to wake up.But I was already out the window and I could see a patisserie down the way.

I’d landed heavily, in a puddle, rainwater sloshing around my feet. When I’d looked back up at the window, the white curtain flapping in the gusty breeze, I’d felt both sadness and relief, the oppositional tug of heaviness and lightness, one lifting me up, one pushing me down. I understood then, Lulu and I had started something, something I’d always wanted, but also something I was scared of getting. Something I wanted more of. And, also, something I wanted to get away from. The truth and its opposite.

I set off for the patisserie not quite knowing what to do, not quite knowing if I should go back, stay another day, but knowing if I did, it would break all this wide open. I bought the croissants, still not knowing what to do. And then I turned a corner and there were the skinheads. And in a twisted way, I was relieved: They would make the decision for me.

Except as soon as I woke up in that hospital, unable to remember Lulu, or her name, or where she was, but desperate to find her, I understood that it was the wrong decision.

“I wascoming back,” I tell Kate. But there’s a razor of uncertainty in my voice, and it cuts my deception wide open.

“You know what I think, Willem?” Kate says, her voice gentle. “I think acting, that girl, it’s the same thing. You get close to something and you get spooked, so you find a way to distance yourself.”

In Paris, the moment when Lulu had made me feel the safest, when she had stood between me and the skinheads, when she had taken care of me, when she became my mountain girl, I’d almost sent her away. That moment, when we’d found safety, I’d looked at her, the determination burning in her eyes, the love already there, improbably after just one day. And I felt it all—the wanting and the needing—but also the fear because I’d seen what losing this kind of thing could do. I wanted to be protected by her love, and to be protected from it.

I didn’t understand then. Love is not something you protect. It’s something you risk.

“You know the irony about acting?” Kate muses. “We wear a thousand masks, are experts at concealment, but the one place it’s impossible to hide is on stage. So no wonder you’re freaked out. And Orlando, well now!”

She’s right, again. I know she is. Petra didn’t do anything today except give me an excuse to pull another runner. But the truth of it is I didn’t really want to pull a runner that day with Lulu. And I don’t want to pull one now, either.

“What’s the worst that happens if you do it your way tonight?” Kate asks.

“She fires me.” But if she does, it’ll be my action that decides it. Not my inaction. I start to smile. It’s tentative, but it’s real.

Kate matches mine with a big American version. “You know what I say: Go big or go home.”

I look at the boat; it’s quiet, but the garden is so lush and well-tended in a way that it never was with us. It is a home, not mine, but someone else’s now.

Go big or go home. I heard Kate say that before and didn’t quite get it. But I understand it now, though I think on this one, Kate has it wrong. Because for me, it’s not go big or go home. It’s go big andgo home.

I need to do one to do the other.