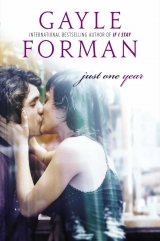

Текст книги "Just One Year"

Автор книги: Gayle Forman

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

Forty-eight

Backstage. It’s the usual craziness, only I feel strangely calm. Linus hustles me to the makeshift dressing room where I change out of my street clothes into Orlando’s clothes, hastily altered to fit me. I put on my makeup. I fold my clothes into the lockers behind the stage. My jeans, my shirt, Lulu’s watch. I hold it in my hand one second longer, feel the ticking vibrate against my palm, and then I put it in the locker.

Linus gathers us into a circle. There are vocal exercises. The musicians tune their guitars. Petra barks last-minute direction, about finding my light and keeping the focus and the other actors supporting me, and just doing my best. She is giving me a piercing, worried look.

Linus calls five minutes and puts on his headset, and Petra walks away. Max has come backstage for tonight’s performance and is sitting on a three-legged stool in the wings. She doesn’t say anything, but just looks at me and kisses two fingers and holds them up in the air. I kiss the same two on my hand and hold them up to her.

“ Break a leg,” someone whispers in my ear. It’s Marina, come up behind me. Her arms quickly encircle me from behind as she kisses me somewhere between my ear and my neck. Max catches this and smirks.

“Places!” Linus calls. Petra is nowhere to be seen. She disappears before curtain and won’t reappear until the show is over. Vincent says she goes somewhere to pace, or smoke, or disembowel kittens.

Linus grabs my wrist. “Willem,” he says. I spin to look at him. He gives a small squeeze and nods. I nod back. “Musicians, go!” Linus commands into his headset.

The musicians start to play. I take my place at the side of stage.

“Light cue one, go,” Linus says.

The lights go up. The audience hushes.

Linus: “Orlando, go!”

I hesitate a moment. Breathe, I hear Kate say. I take a breath.

My heart hammers in my head. Thud, thud, thud. I close my eyes and can hear the ticking of Lulu’s watch; it’s as if I’m still wearing it. I stop and listen to them both before I walk onto the stage.

And then time just stops. It is a year and a day. One hour and twenty-four. It is time, happening, all at once.

The last three years solidify into this one moment, into me, into Orlando. This bereft young man, missing a father, without a family, without a home. This Orlando, who happens upon this Rosalind. And even though these two have known each other only moments, they recognize something in each other.

“The little strength that I have, I would it were with you,” Rosalind says, cracking it all wide open.

Who takes care of you?Lulu asked, cracking me wide open.

“Wear this for me,” Marina says as Rosalind, handing me the prop chain from around her neck.

I’ll be your mountain girl and take care of you, Lulu said, moments before I took the watch from her wrist.

Time is passing. I know it must be. I enter the stage, I exit the stage. I make my cues, hit my marks. The sun dips across the sky and then dances toward the horizon and the stars come out, the floodlights go on, the crickets sing. I sense it happening as I drift above it somehow. I am only here, now. This moment. On this stage. I am Orlando, giving myself to Rosalind. And I am Willem, too, giving myself to Lulu, in a way that I should’ve done a year ago, but couldn’t.

“You should ask me what time o’ day: there’s no clock in the forest,” I say to my Rosalind.

You forget, time doesn’t exist anymore. You gave it to me, I said to my Lulu.

I feel the watch on my wrist that day in Paris; I hear it ticking in my head now. I can’t tell them apart, last year, this year. They are one and the same. Then is now. Now is then.

“I would not be cured, youth,” my Orlando tells Marina’s Rosalind.

“I would cure you, if you would but call me Rosalind,” Marina replies.

I’ll take care of you, Lulu promised.

“By my troth, and in good earnest, and so God mend me, and by all pretty oaths that are not dangerous,” Marina’s Rosalind says.

Iescaped danger, Lulu said.

We both did. Something happened that day. It’s still happening. It’s happening up here on this stage. It was just one day and it’s been just one year. But maybe one day is enough. Maybe one hour is enough. Maybe time has nothing at all to do with it.

“Fair youth, I would I could make thee believe I love,” my Orlando tells Rosalind.

Define love, Lulu had demanded. What would “being stained” look like?

Like this, Lulu.

It would look like this.

• • •

And then it’s over. Like a great wave crashing onto a shore, the applause erupts and I’m here, on this stage, surrounded by the shocked and delighted smiles of my castmates. We are grasping hands and bowing and Marina is pulling me out front for our curtain call and then stepping to the side and gesturing for me to walk ahead and I do and the applause grows even louder.

Backstage, it is madness. Max is screaming. And Marina is crying and Linus is smiling, although his eyes keep darting to the side entrance that Petra left from hours ago. People are surrounding me, patting me on the back, offering congratulations and kisses and I’m here but I’m not—I’m still in some strange limbo where the boundaries of time and place and person don’t exist where I can be here and in Paris, where it can be now and then, where I’m me and also Orlando.

I try to stay in this place as I change out of my clothes, scrub the makeup off my face. I look at myself in the mirror and try to digest what I just did. It feels completely unreal, and like the truest thing I have ever done. The truth and its opposite. Up on stage, playing a role, revealing myself.

People gather round me. There is talk, of parties, celebration, a cast party tonight, even though the show doesn’t wrap for two more weeks and to celebrate now is technically bad luck. But it seems like everyone has given up on luck tonight. We make our own.

Petra comes backstage, stone-faced and not saying a word. She walks right past me. Goes straight to Linus.

I leave the backstage and go out the gate that serves as a stage door. Max is at my side, jumping up and down like an exuberant puppy. “So was Marina a decent kisser?” she asks me.

“I’m sure she was glad not to be kissing Jeroen,” Vincent says, and I laugh.

Outside, I scan the area for my friends. I’m not quite sure who will be here. And then I hear her call my name.

“Willem!” she says again.

It’s Kate, charging toward me, a blur of gold and red. My heart seems to expand as she leaps into my arms and we spin around.

“You did it. You did it. You did it!” she murmurs in my ear.

“I did it. I did it. I did it.” I repeat, laughing with joy and relief and awe at the direction this day has taken.

Someone taps me on the shoulder. “You dropped something.”

“Oh, right. Your flowers,” Kate says, leaning over to pick up a bouquet of sunflowers. “For your stunning debut.”

I take the flowers.

“How do you feel?” she asks.

I have no answer, no words. I just feel full. I try to explain it but then Kate interrupts: “Like you just had the best sex in the world?” And I laugh. Yeah, something like that. I take her hand and kiss it. She twines an arm around my waist.

“Ready to meet your adoring public?” she asks.

I’m not. Right now, I just want to savor this. With the person who helped make it happen. Leading her by the hand, I take us over to a quiet bench under a nearby gazebo and attempt in some way to articulate what just happened.

“How did that happen?” is all I can think to ask.

She holds my hands in hers. “Do you really need to ask that?”

“I think I do. It felt like something otherworldly.”

“Oh, no,” she says, laughing. “I believe in the muse and all, but don’t go attributing that performance to one of your accidents. It was all you up there.”

It was. And it wasn’t. Because I wasn’t alone up there.

We sit there for a little while longer. I feel my whole body buzzing, humming. This night is perfect.

“I think your groupies are waiting,” Kate says after a while, gesturing behind me. I turn around and there are Broodje, Henk, W, Lien, and a few other people, watching us curiously. I take Kate by the hand and introduce them to the boys.

“You’re coming to our party, aren’t you?” Broodje asks.

“ Ourparty?” I ask.

Broodje manages to look a tiny bit sheepish. “It’s hard to un-throw a party at short notice.”

“Especially since he has now invited the cast, and about half the audience,” Henk says.

“That’s not true!” Broodje says. “Not half. Just a couple of Canadians.”

I roll my eyes and laugh. “Fine. Let’s go.”

Lien laughs and takes my hand. “I’m going to say goodnight. One of us should be coherent tomorrow. It’s moving day.” She kisses W. Then me. “Well done, Willem.”

“I’m going to follow her out of the park,” Kate says. “This city confounds me.”

“You’re not coming?” I ask.

“I have some things I need to do first. I’ll come later. Prop the door open for me.”

“Always,” I say. I go to kiss her on the cheek and she whispers into my ear, “I knew you could do it.”

“Not without you,” I say.

“Don’t be silly. You just needed a pep talk.”

But I don’t mean the pep talk. I know Kate believes that I have to commit, to not rely on the accidents, to take the wheel. But had we not met in Mexico, would I be here now? Was it accidents? Or will?

For the hundredth time tonight, I’m back with Lulu, on Jacques’s barge, the improbably named Viola. She’d just told me the story of double happiness and we were arguing over the meaning. She’d thought it meant the luck of the boy getting the job and the girl. But I’d disagreed. It was the couplet fitting together, the two halves finding each other. It was love.

But maybe we were both wrong, and both right. It’s not either or, not luck orlove. Not fate orwill.

Maybe for double happiness, you need both.

Forty-nine

Inside the flat, it is complete mayhem. More than fifty people, from the cast, from Utrecht, even old school friends from my Amsterdam days. I have no idea how Broodje dug everyone up so fast.

Max pounces on me as soon as she comes in the door, followed by Vincent. “Holy. Shit,” Max says.

“You might’ve mentioned you could act!” Vincent adds.

I smile. “I like to preserve a bit of mystery.”

“Yeah, well, everyone in the cast is bloody delighted,” says Max. “Except Petra. She’s pissy as ever.”

“Only because her understudy just completely cockblocked her star. And now she has to decide whether to put up a lame, and I mean that both literally and figuratively, star, or let you carry us home,” Vincent says.

“Decisions, decisions,” Max adds. “Don’t look now but Marina is giving you the fuck-me eyes again.”

We all look. Marina is staring right at me and smiling.

“And don’t even deny it, unless it’s meshe wants to shag,” Max says.

“I’ll be right back,” I tell Max. I go over to her to where Marina’s standing by the table Broodje has turned into the bar. She has a jug of something in her hand. “What do you have there?” I ask.

“Not entirely sure. One of your mates gave it to me, promised me no hangover. I’m taking him at his word.”

“That’s your first mistake right there.”

She runs a finger along the top of the rim. “I have a feeling I’m long past making my first mistake.” She takes a gulp of her drink. “Aren’t you drinking?”

“I already feel drunk.”

“Here. Catch up with yourself.”

She hands me her glass and I take a sip. I taste the sour tequila that Broodje now favors, mixed with some other orange-flavored booze. “Yeah. No hangover from this. Definitely not.”

She laughs, touches my arm. “I’m not going to tell you how fantastic you were tonight. You’re probably sick of hearing it.”

“Do you everget sick of hearing it?”

She grins. “No.” She looks away. “I know what I said earlier today, about after the show, but all the rules seem to be getting broken today. . . .” She trails off. “So really, can three weeks make much of a difference?”

Marina is sexy and gorgeous and smart. And she’s also wrong. Three weeks can make all the difference. I know that because one day can make all the difference.

“Yes,” I tell Marina. “They can.”

“Oh,” she says, sounding surprised, a little hurt. Then: “Are you with someone else?”

Tonight on that stage, it felt like I was. But that wasa ghost. Shakespeare’s full of them. “No,” I tell her.

“Oh, I just saw you, with that woman. After the show. I wasn’t sure.”

Kate. The need to see her feels urgent. Because what I want is so clear to me now.

I excuse myself from Marina and poke through the flat, but there’s no sign of Kate. I go downstairs to see if the door is still propped open. It is. I bump into Mrs. Van der Meer again, out walking her dog. “Sorry about all the noise,” I tell her.

“It’s okay,” she says. She looks upstairs. “We used to have some wild parties here.”

“You lived here back when it was a squat?” I ask, trying to reconcile the middle-aged vrouwwith the young anarchists I’ve seen in pictures.

“Oh, yes. I knew your father.”

“What was he like then?” I don’t know why I’m asking that. Bram was never the hard one to crack.

But Mrs. Van der Meer’s answer surprises me. “He was a bit of a melancholy young man,” she says. And then her eyes flicker up to the flat, like she’s seeing him there. “Until that mother of yours showed up.”

Her dog yanks on the leash and she sets off, leaving me to ponder how much I know, and don’t know, about my parents.

Fifty

The phone is ringing. And I’m sleeping.

I fumble for it. It’s next to my pillow.

“Hello,” I mumble.

“Willem!” Yael says in a breathless gulp. “Did I wake you?”

“Ma?” I ask. I wait to feel the usual panic but none comes. Instead, there’s something else, a residue of something good. I rub my eyes and it’s still there, floating like a mist: a dream I was having.

“I talked to Mukesh. And he worked his magic. He can get you out Monday but we have to book now. We’ll do an open-ended ticket this time. Come for a year. Then decide what to do.”

My head is hazy with lack of sleep. The party went until four. I fell asleep around five. The sun was already up. Slowly, yesterday’s conversation with my mother comes back to me. The offer she made. How much I wanted it. Or thought I did. Some things you don’t know you want until they’re gone. Other things you think want, but don’t understand you already have them.

“Ma,” I say. “I’m not coming back to India.”

“You’re not?” There’s curiosity in her voice, and disappointment, too.

“I don’t belong there.”

“You belong where I belong.”

It’s a relief, after all this time, to hear her say so. But I don’t think it’s true. I’m grateful that she has made a new home for herself in India, but it’s not where I’m meant to be.

Go big and go home.

“I’m going to act, Ma,” I say. And I feel it. The idea, the plan, fully formed since last night, maybe since much longer. The urgency to see Kate, who never did show up at the party, courses through me. This is one chance I’m not going to let slip through my fingers. This issomething I need. “I’m going to act,” I repeat. “Because I’m an actor.”

Yael laughs. “Of course you are. It’s in your blood. Just like Olga.”

The name is instantly familiar. “Olga Szabo, you mean?”

There’s a pause. I can feel her surprise crackle through the line. “Saba told you about her?”

“No. I found the pictures. In the attic. I meant to ask you about them but I didn’t, because I’ve been busy . . .” I trail off. “And because we never really talked about these things.”

“No. We never did, did we?”

“Who was she? Saba’s girlfriend?”

“She was his sister,” she replies. And I should be surprised, but I’m not. Not at all. It’s like the pieces of a puzzle slotting together.

“She would have been your great aunt,” Yael continues. “He always said she was an incredible actress. She was meant to go to Hollywood. But then the war came and she didn’t survive.”

She didn’t survive. Only Saba did.

“Was Szabo her stage name?” I ask.

“No. Szabo was Saba’s surname before he emigrated to Israel and Hebreified it. Lots of Europeans did that.”

To distance himself, I think. I understand that. Though he couldn’t really distance himself. All those silent films he took me to. The ghosts he held at bay, and held close.

Olga Szabo, my great aunt. Sister to my grandfather, Oskar Szabo, who became Oskar Shiloh, father of Yael Shiloh, wife of Bram de Ruiter, brother of Daniel de Ruiter, soon to be father of Abraão de Ruiter.

And just like that, my family grows again.

Fifty-one

When I emerge from my bedroom, Broodje and Henk are just waking up and are surveying the wreckage like army generals who have lost a major ground battle.

Broodje turns to me, his face twisted in apology. “I’m sorry. I can clean it all later. But we promised we’d meet W at ten to help him move. And we’re already late.”

“I think I’m going to be sick,” Henk says.

Broodje picks up a beer bottle, two-thirds full of cigarette butts. “You can be sick later,” he says. “We made a promise to W.” Broodje looks at me. “And to Willy. I’ll clean the flat later. And Henk’s vomit, which he’s going to keep corked for now.”

“Don’t worry about it,” I say. “I’ll clean it all. I’ll fix everything!”

“You don’t have to be so cheerful about it,” Henk says, wincing and touching his temples.

I grab the keys from the counter. “Sorry,” I say, not sorry at all. I head to the door.

“Where are you going?” Broodje.

“To take the wheel!”

• • •

I’m unlocking my bike downstairs when my phone rings. It’s her. Kate.

“I’ve been calling you for the last hour,” I say. “I’m coming to your hotel.”

“My hotel, huh?” she says. I can hear the smile in her voice.

“I was worried you’d leave. And I have a proposition for you.”

“Well, propositions arebest proposed in person. But sit tight because I’m actually on my way to you. That’s why I’m calling. Are you home?”

I think of the flat, Broodje and Henk in their boxers, the unbelievable mess. The sun is out, really out, for the first time in days. I suggest we meet at the Sarphatipark instead. “Across the street. Where we were yesterday,” I remind her.

“Proposition downgraded from a hotel to a park, Willem?” she teases. “I’m not sure whether to be flattered or insulted.”

“Yeah, me neither.”

I go straight to the park and wait, sitting down on one of the benches near the sandpit. A little boy and girl are discussing their plans for a fort.

“Can it have one hundred towers?” the little boy asks. The girl says, “I think twenty is better.” Then the boy asks, “Can we live there forever?” The girl considers the sky a moment and says, “Until it rains.”

By the time Kate shows up, they’ve made significant progress, digging a moat and constructing two towers.

“Sorry it took so long,” Kate says, breathless. “I got lost. This city of yours, it runs in circles.”

I start to explain about the concentric canals, the Ceintuurbaan being a belt that goes around the waist of the city. She waves me off. “Don’t bother. I’m hopeless.” She sits down next to me. “Any word from Frau Directeur?”

“Total silence.”

“That sounds ominous.”

I shrug. “Maybe. Nothing I can do. Anyway, I have a new plan.”

“Oh,” Kate says, widening her already big green eyes. “You do?”

“I do. In fact, that’s what my proposition is about.”

“The thick plottens.”

“What?”

She shakes her head. “Never mind.” She crosses her legs, leans in toward me. “I’m ready. Proposition me.”

I take her hand. “I want you.” I pause. “To be my director.”

“Isn’t that a little like shaking hands after making love?” she asks.

“What happened last night,” I begin, “it happened because of you. And I want to work with you. I want to come study with Ruckus. Be an apprentice.”

Kate’s eyes slit into smiles. “How do you know about our apprenticeships?” she drawls.

“I may have looked at your website one or a hundred times. And I know you mostly work with Americans, but I grew up speaking English, I act in English. Most of the time, I dream in English. I want to do Shakespeare. In English. I want to do it. With you.”

The grin has disappeared from Kate’s face. “It wouldn’t be like last night—Orlando on a main stage. Our apprentices do everything. They build sets. They work tech. They study. They act in the ensemble. I’m not saying you wouldn’t play principal roles one day—I would not rule that out, not after last night. But it would take a while. And, there are visa issues to consider, not to mention the union, so you couldn’t come over expecting the spotlight. And I’ve told David he needs to meet you.”

I look at Kate and am about to say that I wouldn’t expect that, that I’d be patient, that I know how to build things. But I stop myself because it occurs to me that I don’t need to convince herof anything.

“Where do you think I was last night?” she asks. “I was waiting for David to get back from his Medea, so I could tell him about you. Then I arranged for him to get his ass on a plane so he could see you tonight before that invalid comes back. He’s on his way, and in fact, I have to leave soon to go to the airport to meet him. After all this trouble, they’d better put you on again, otherwise, you’re going to have to do it solo for him.”

She laughs. “I’m kidding. But Ruckus is a small operation so we make decisions like this communally. That’s another thing you have to be prepared for, how dysfunctionally co-dependent we all are.” She throws up her arms. “But every family is like that.”

“So, wait? You were going to ask me?”

The grin is back. “Was there any doubt? But it pleases me no end, Willem, that youasked me. It shows you’ve been paying attention, which is what a director wants in an actor.” She taps her temple. “Also, very clever of you to move to the States. Good for your career but also it’s where your Lulu is from.”

I think of Tor’s letter, only today the regret and recrimination is gone. She looked for me. I looked for her. And last night, in some strange way, we found each other.

“That’s not why I want to go,” I tell Kate.

She smiles. “I know. I’m just teasing. Though I think you’ll really take to Brooklyn. It has a lot in common with Amsterdam. The brownstones and the rowhouses, the loving tolerance of eccentricity. I think you’ll feel right at home.”

When she says that a feeling comes over me. Of pausing, of resting, of all the clocks in the world going quiet.

Home.