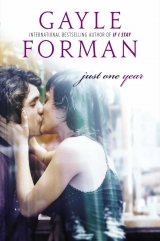

Текст книги "Just One Year"

Автор книги: Gayle Forman

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

Thirty-five

“Name.”

“Willem. De Ruiter.” It comes out a whisper.

“Come again.”

I clear my throat. Try again. “Willem de Ruiter.”

Silence. I can feel my heartbeat, in my chest, my temple, my throat. I can’t remember ever being nervous like this before and I don’t quite understand it. I’ve never had stage fright. Not even that first time with the acrobats, not even going on with Guerrilla Will, in French. Not even the first time Faruk shouted action and the cameras rolled and I had to speak Lars Von Gelder’s lines, in Hindi.

But now, I can barely say my name out loud. It’s as if, unbeknownst to me, there is a volume switch on me and someone has turned it all the way down. I squint my eyes and try to peer into the audience, but the bright lights are rendering whoever is out there invisible.

I wonder what they’re doing. Are they looking at the ridiculous headshot I scrambled to put together? Daniel took it of me in the Sarphatipark. And then we’d printed my Guerrilla Will stats on the back. It doesn’t look half bad from a distance. I have several plays to my credit, all of them Shakespearian. It’s only if you inspect it closely you see that the picture is shitty quality, pixelated to the extreme, taken on a phone and printed at home. And my acting credentials, well, Guerrilla Will isn’t exactly repertory theatre. I’d seen some of the headshots of the other actors. They came from all over Europe—the Czech Republic, Germany, France and the UK, as well as here—and had real plays under their belts. Better photos, too.

I take a deep breath. At least I havea head shot. Thanks to Kate Roebling. I called her at the last minute for advice because I’ve never auditioned before. With Guerrilla Will, Tor decided what role you’d play. There was some sniping about this, but I didn’t care. The money was split equally, no matter how many lines you had.

“Ahh, yes, Willem,” a disembodied voice says. It sounds bored before I’ve even begun. “What will you be reading for us today?”

The play being produced this summer is As You Like It, one I’ve never seen or heard much about. When I stopped in the theater last week, they told me I could prepare any Shakespearian monologue. In English. Obviously. Kate had told me to take a look at As You Like It. That I might find something really meaty in it.

“Sebastian, from Twelfth Night,” I say. I decided to put together three shorter Sebastian speeches. Easiest to do that. It was the last part I played. And I still remembered most of the lines.

“Whenever you’re ready.”

I try to remember Kate’s words, but they swirl in my head like a foreign language I barely know. Choose something you feel? Be who you are, not who they want you to be? Go big or go home?And there was something else, something she told me before she rang off. It was important. But I can’t remember it now. At this point, it’ll be enough to remember my lines.

A throat clears. “Whenever you’re ready.” It’s a woman’s voice this time, in a tone that says: Get on with it.

Breathe. Kate said to breathe. That much I remember. So I breathe. And then I begin:

“By your patience, no. My stars shine darkly over me: the malignancy of my fate might perhaps distemper yours.”

The first lines come out. Not too bad. I continue.

“Therefore I shall crave of you your leave that I may bear my evils alone.”

The words start to flow out of me. Not as they did last summer in that endless array of parks and squares and plazas. Not haltingly, as they did in Daniel’s bathroom, where I practiced them all weekend, to the mirror, to the tiles, and on occasion, to Daniel himself.

“If the heavens had been pleased, would we had so ended!”

The words come differently now. Understood in a fresh way. Sebastian is not just some aimless drifter, going where the wind blows him. He’s someone recovering, rubbed raw and unsure by his spate of bad fortune, by the malignancy of his fate.

“She bore a mind that envy could not but call fair,” I say and it’s Lulu I see, on that hot English night, the last time I spoke these words in front of an audience. The faint smile on her lips.

“She is drowned already sir, with salt water, though I seem to drown her remembrance again with more.”

And then it’s over. There’s no applause, only a loud silence. I can hear my breathing, my heartbeat, still hammering. Aren’t the nerves supposed to go away once you are on stage? Once you’ve finished?

“Thank you,” the woman says. Her words are clipped, generic, no actual gratitude in them. For a second, I think perhaps I should thank them.

But I don’t. I leave the stage in a bit of a daze wondering what just happened. As I walk up the aisle, I see the director and producer and stage manager (Kate told me whom to expect) already conferring about someone else’s headshot. Then I’m squinting in the bright light of the lobby. I rub my eyes. I’m unsure of what to do next.

“Glad that’s over?” a skinny guy asks me in English.

“Yeah,” I say reflexively. Only it’s not true. Already, I’m starting to feel this melancholy set in, like the first cold fall day after a hot summer.

“What brought about the change of mind?” Kate had asked me on the phone. We hadn’t been in any kind of contact since Mexico, and when I told her my plans, she sounded surprised.

“Oh, I don’t know.” I’d explained to her about finding Twelfth Nightand then being told about the auditions, about being in the right place at the right time.

“So how’d it go?” the skinny guy asks me now. He has a copy of As You Like Itin his hand, and his knee is thumping, up-down-up-down.

I shrug. I have no idea. Truly. I don’t.

“I’m going for Jaques. What about you?”

I look at the play, which I haven’t even read. I just figured I’d get what they gave me, as it always was with Tor. With a sinking feeling, I begin to suspect that wasn’t the right way to go.

And it’s then I remember what Kate said on the phone, after I explained the roundabout way I’d come to audition.

“ Commit, Willem. You have to commit. To something.”

Like so many of the important things these days, the memory comes too late.

Thirty-six

Aweek goes by, I hear nothing. The skinny guy I’d spoken to, Vincent, had said there’d be a series of callbacks before final casting. I don’t get called. I put it behind me and get back to work on Daniel’s flat, channeling so much energy into my tiling that Daniel and I finish the bathroom a couple of days ahead of schedule and get started on the kitchen. We take the metro out to IKEA to pick cabinets. We’re in a showcase kitchen with cabinets the color of red nail varnish when my phone rings.

“Willem, this is Linus Felder from the Allerzielentheater.”

My heart thuds like I’m on stage all over again.

“I need you to learn Orlando’s opening speech and come in tomorrow morning at nine. Can you manage that?” he asks.

Of course I can manage it. I want to tell him that I’ll more than manage it. “Sure,” I say. And before I have a chance to ask any particulars, Linus hangs up.

“Who was that?” Daniel asks.

“The stage manager from that play I auditioned for. He wants me to come back in. To read for Orlando. The lead.”

Daniel jumps up and down like an excited child, knocking over the prop mixer in the show kitchen. “Oh, shit.” He pulls us away, whistling innocently.

I leave Daniel in IKEA and spend the rest of the day in the drizzle at the Sarphatipark, memorizing the speech. When it’s a decent hour in New York, I call Kate for more advice but I wake her up because it turns out she’s in California now. Ruckus is about to start a six-week tour of Cymbelineon the West Coast before coming to the UK in August for various festivals. When I hear this, I’m almost embarrassed to ask her for help. But, generous as always, she takes a few minutes to tell me what to expect on a callback. I might read a bunch of scenes and a bunch of parts, opposite several actors, and even though they’ve asked me to read Orlando, I shouldn’t assume that’s the role I’m up for. “But it’s promising they’ve asked you to read him,” she says. “It’s quite a role for you.”

“How do you mean?”

She sighs, noisily. “You stillhaven’t read the play?”

I’m embarrassed all over again. “I will, I promise. Later today.”

We talk a little more. She says she’s planning on spending nonfestival weekends traveling out of the UK, so maybe she’ll come to Amsterdam. I tell her she’s welcome any time. And then she reminds me again to read the play.

• • •

Late that night, after I’ve read the opening monologue so many times I could recite it in my sleep, I start on the rest of the play. I’m falling asleep at this point and it’s a little difficult to get into. I try to see what Kate means about Orlando. I suppose it’s that he meets a girl and falls in love with her and then meets her again but she’s disguised. Except Orlando gets a happy ending.

• • •

When I arrive at the theater the next morning, it’s almost empty, and dark except for a single lamp burning on the stage. I sit down in the last seat, and a short while later, the house lights flicker on. Linus strolls in, clipboard in hand, and behind him, Petra, the diminutive director.

There are no pleasantries. “Whenever you’re ready,” Linus says.

This time, I am ready. I’m determined to be.

Except I’m not. I get the lines right, but as I say one, then the next, I can hear myself say them and then I wonder how they sounded, did I hit the right beat? And the more I do that, the stranger the words start to sound, in the way that a perfectly normal word can start to sound like gibberish. I try to focus, but the harder I try, the harder it becomes, and then I hear a cricket chirping somewhere backstage and it sounds like the lobby of the Bombay Royale, and then I’m thinking about Chaudhary and his cot and Yael and Prateek and I’m everywhere in the world except in this theater.

By the time I finish, I’m furious with myself. All that practice, and it was for shit. The Sebastian monologue, which I didn’t even care that much about, was infinitely better than this.

“Can I try that again?” I ask.

“No need,” Petra says. I hear her and Linus murmuring.

“Really. I know I could do better.” There’s a jaunty smile on my face, which may be my finest acting of the day. Because really, I don’t know that I could do better. This wasme trying.

“It was fine,” Petra barks. “Come back Monday at nine. Linus will get your paperwork before you leave.”

Is that it? Did I just get the part of Orlando?

Maybe I shouldn’t be so surprised. After all, it wasthat easy with the acrobats and with Guerrilla Will and even with Lars Von Gelder. I should be elated. I should be relieved. But, weirdly, all I feel is let down. Because this matters to me now. And something tells me if it matters, maybe it shouldn’t be easy.

Thirty-seven

JULY

Amsterdam

“Hey, Willem, how are you feeling today?”

“I’m fine, Jeroen. How are you?”

“Oh, you know, the gout is acting up.” Jeroen pounds his chest and heaves a cough.

“Gout is in your leg, you twat,” Max says, sliding into the seat next to me.

“Oh, right.” Jeroen flashes her his most charming smile as he limps away, laughing.

“What a tosser!” Max says, dropping her bag at my feet. “If I have to kiss him, I swear, I might puke on the stage.”

“Pray for Marina’s health then.”

“Wouldn’t mind kissing her though.” Max grins and looks at Marina, the actress who plays Rosalind opposite Jeroen’s Orlando. “Ahh, lovely Marina, self-serving though it is, wouldn’t want her to fall ill. She’s so lovely. And, besides if she couldn’t go on, I’d have to kiss that git. He’sthe one who I want to get sick.”

“But he doesn’t get sick,” I tell Max, as though she needs reminding. Since being cast as his understudy, I have heard, endlessly, relentlessly, how in his dozen years of doing theater, Jeroen Gosslers has never, ever missed a performance, not even when he was throwing up with the flu, not even when he had lost his voice, not even when his girlfriend went into labor with their daughter hours before curtain. In fact, Jeroen’s spotless record is apparently why I was given this shot in the first place, after the actor originally cast as an understudy booked a Mentos ad that would’ve required him missing three rehearsals to shoot the commercial. Three rehearsals, for an understudy who will never go on. Petra demands everything of her understudies, while at the same time demanding nothing of them.

As required, I’ve been at the theater every day since that very first table read, when the cast sat around a long wooden scuffed table on the stage, going through the text line by line, parsing meaning, deconstructing what this word meant, how that line should be interpreted. Petra was surprisingly egalitarian, open to almost anyone’s opinions about what Sad Lucretia meant or why Rosalind persisted on keeping up her disguise for so long. If one of Duke Frederick’s men wanted to interpret an exchange between Celia and Rosalind, Petra would entertain it. “If you are at this table, you have a right to be heard,” she said, magnanimously.

Max and I, however, were conspicuously not at the table, but rather seated a few paces away, near enough to hear, but far enough that for us to participate in the discussion made us feel like interlopers. At first, I wondered if this was unintentional. But after hearing Petra repeat, several times, that “performing is so much more than speaking lines. It’s about communicating with your audience through every gesture, every word unsaid,” I understood it was completely intentional.

It seems almost quaint now, that I worried about it being tooeasy. Though it has turned out to be easy, only not in the way I thought. Max and I are the only understudies who don’t have any actual roles in the play. We occupy a strange place in the cast. Semi-cast members. Shadow-cast members. Seat-warmers. Very few people in the cast speak to us. Vincent does. He got his Jaques after all. And Marina, who plays Rosalind, does as well, because she is uniquely gracious. And of course Jeroen makes it a point to talk to me every day, though I wish he wouldn’t.

“So, what we got on today?” Max asks in her London cockney. Like me, she’s a mutt; her father is Dutch from Surinam and her mother is from London. The cockney gets stronger when she drinks too much, though when she reads Rosalind, her English goes silky as the British Queen’s.

“They’re going over the fight scene choreography,” I tell her.

“Oh, good. Maybe that ponce will actually get hurt.” She laughs and runs a hand through her spiky hair. “Wanna run lines later? Won’t be much of a chance once we start tech.”

Soon, we move the set out of the theater for the final five days of tech rehearsals and dress rehearsals at the amphitheater in Vondelpark where the show will go up for six weekends. In two Fridays, we’ll have our soft opening, and then Saturday, the hard opening. For the rest of the cast, this is the payoff for all the work. For Max and me, it’s when we cash out, when any semblance of us being in the cast disappears. Linus has told us to make sure we know the entire play, all the blocking, by heart, and we’re to trail Jeroen and Marina through the first tech rehearsal. This is as close to the action as we get. Not once has Linus or Petra given us any direction or asked us to run lines or gone over any aspect of the play. Max and I run lines incessantly, the two of us. I think it’s how we make ourselves feel like we’re actually a part of the production.

“Can we do the Ganymede parts? You know I like those best,” Max says.

“Only because you get to be a boy.”

“Well, natch. I prefer Rosalind when she’s channeling her man. She’s such a simp in the beginning.”

“She’s not a simp. She’s in love.”

“At first sight.” She rolls her eyes. “A simp. She’s ballsier when she’s pretending to have balls.”

“Sometimes it’s easier to be someone else,” I say.

“I should think so. It’s why I became a bleeding actor.” And then she looks at me and snorts with laughter. We may memorize the lines. We may know the blocking. We may show up. But neither one of us is an actor. We are seat warmers.

Max sighs and kicks her feet up onto the chair, daring a wordless reprimand from Petra and a follow-up telling off from Linus, or, as Max calls him, the Flunky.

Up on stage, Jeroen is arguing with the choreographer. “That’s not really working for me. It doesn’t feel authentic,” he says. Max rolls her eyes again but I sit up to listen. This happened about every other day during the blocking, Jeroen not “feeling” the movements and Petra changing them, but Jeroen not feeling the new blocking either, so most of the time, she changed it back. My script is a crosshatch of scribbles and erasures, a road map of Jeroen’s quest for authenticity.

Marina is sitting on the cement pilings on the stage next to Nikki, the actress playing Celia. They both look bored as they watch the fight choreography. For a second Marina catches my eye and we exchange a sympathetic smile.

“I saw that,” Max says.

“Saw what?”

“Marina. She wants you.”

“She doesn’t even know me.”

“That may be the case, but she was giving you fuck-me eyes at the bar last night.”

Every night after rehearsal, most of the cast goes to a bar around the corner. Because we are either provocative or masochistic, Max and I go along with them. Usually we wind up sitting at the long wooden bar on our own or at a table with Vincent. There never seems to be room at the big table for Max and me.

“She was not giving me fuck-me eyes.”

“She was giving oneof us fuck-me eyes. I haven’t gotten any Sapphic vibes off her, though you never can tell with Dutch girls.”

I look at Marina. She’s laughing at something Nikki said, as Jeroen and the actor playing Charles the wrestler work some fake punches with the fight choreographer.

“Unless you don’t like girls,” Max continues, “but I’m not getting that vibe off you either.”

“I like girls just fine.”

“Then why do you leave the bar with me every night?”

“Are you not a girl?”

Max rolls her eyes. “I am sorry, Willem, but charming as you are, it’s not going to happen with us.”

I laugh and give Max a wet kiss on the cheek, which she wipes off, with excess drama. Up on stage, Jeroen attempts a false punch at Charles and stumbles over himself. Max claps. “Mind that gout,” she calls.

Petra swerves around, her sharp eyes full of disapproval. Max pretends to be absorbed in her script.

“Fuck running lines,” Max whispers when Petra’s attention is safely returned to the stage. “Let’s get drunk.”

• • •

That night, over drinks at the bar, Max asks me, “So why don’t you?”

“Why don’t I what?”

“Get off with a girl. If not Marina, one of the civilians at the bar.”

“Why don’t you?” I ask.

“Who’s to say I don’t?”

“You leave with me every night, Max.”

She sighs, a big deep sigh that seems a lot older than Max, who is only a year older than me. Which is why she doesn’t mind seat-warming, she says. My time will come.She makes a slash mark over her chest. “Broken heart,” she says. “Dykes take dog-years to heal.”

I nod.

“So what about you?” Max says. “Broken heart?”

At times, I’d thought it was something like that—after all, I’d never been quite so strung out about a girl. But it’s a funny thing because since that day with Lulu in Paris, I’ve reconnected with Broodje and the boys, I’ve visited my mother and have been talking to her again, and now I’m living with Uncle Daniel. And I’m acting. Okay, perhaps not acting, exactly. But not accidentally acting, either. And just in general, I’m better. Better than I’ve been since Bram died, and in some ways, better than I was even before that. No, Lulu didn’t break my heart. But I’m beginning to wonder if in some roundabout way, she fixed it.

I shake my head.

“So what are you waiting for?” Max asks me.

“I don’t know,” I answer.

But one thing I do know: Next time, I’ll know it when I find it.

Thirty-eight

Before Daniel leaves, we hang the last of the kitchen cabinets. The kitchen is almost finished. The plumber will come to install the dishwasher and we’ll put in the backsplash and then that’s that. “We’re nearly there,” I say.

“Just have to fix the buzzer and tackle your shit in the attic,” Daniel says.

“Right. The shit in the attic. How much is there?” I ask. I don’t remember putting that many boxes up there.

But Daniel and I lug down at least a dozen boxes with my name on them. “We should just throw it all away,” I say. “I’ve gone this long without.”

He shrugs. “Whatever you want.”

Curiosity gets me. I open one box, papers and clothes from my dorm, not sure why I kept them. I put them in the garbage. I go through another and do the same. But then I come upon a third box. Inside are colored folders, the kind Yael used to keep patient records in, and I think the box must be mislabeled with my name. But then I see a sheet of paper sticking out of one of the folders. I pick it up.

The wind in my hair

Wheels bounce over cobblestones

As big as the sky

A memory rushes back: “It doesn’t rhyme,” Bram had said when I’d showed it to him, so full of pride because the teacher had asked me to read it to the entire class.

“It’s not supposed to. It’s a haiku,” Yael had said, rolling her eyes at him and bestowing upon me a rare conspiratorial smile.

I pull out the folder. Inside is some of my old schoolwork, my early writing, math tests. I look in another folder: not schoolwork but drawings of a ship, a star of David that Saba taught me to do with two triangles. Pages and pages of this stuff. Unsentimental Yael and clutter-phobic Bram never displayed things like this. I assumed they threw it away.

In another box, I find a tin full of ticket stubs: airplane tickets, concert tickets, train tickets. An old Israeli passport, Yael’s, full of stamps. Beneath that, I uncover a couple of very old black-and-white photos. It takes me a moment to recognize that they’re of Saba. I’ve never seen him this young before. I hadn’t realized any of these photos had survived the war. But it’s unmistakably him. The eyes, they are Yael’s. And mine, too. In one photo, he has his arm slung over a pretty girl, all dark hair and mystery eyes. He looks at her adoringly. She looks vaguely familiar, but it can’t be Naomi, whom he didn’t meet until after the war.

I look for more old photos of Saba and the girl, but find just an odd newspaper clipping of her in a plastic liner. I peer closer. She’s wearing a fancy dress and is flanked by two men in tuxedoes. I hold it up to the light. The faded writing is in Hungarian, but there’s a caption with names: Peter Lorre, Fritz Lang—Hollywood names I recognize—and a third name, Olga Szabo, which I don’t.

I set the photos aside and keep digging. In another box, there are endless keepsakes. More papers. And then in another box, a large manila envelope. I open it up and out tumbles more photos: me, Yael, and Bram, on holiday in Croatia. I remember again how Bram and I walked to the docks every morning to buy fresh fish that no one really knew how to cook. There’s another photo: us bundled up for skating the year the canals froze over and everyone took to their skates. And another: celebrating Bram’s fortieth birthday with that massive party that spilled off the boat, onto the pier, onto the street, until all the neighbors came and it became a block party. There are the outtakes from the architectural magazine shoot, the shot of the three of us before I was cropped out. When I get to the bottom of the pile, there’s one photo left, stuck to the envelope. I have to gently pry it away.

The breath that comes out of me isn’t a sigh or a sob or a shudder. It’s something alive, like a bird, wings beating, taking flight. And then it’s gone, off into the quiet afternoon.

“Everything okay?” Daniel asks me.

I stare at the shot. The three of us, from my eighteenth birthday, not the photo I lost, but a different picture, taken from a different perspective, from someone else’s camera. Another accidental picture.

“I thought I’d lost this,” I say, gripping the picture.

Daniel cocks his head to the side and scratches at his temple. “I’m always losing things, and then I find them again in the strangest places.”