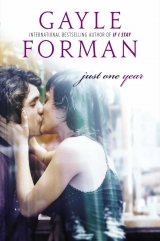

Текст книги "Just One Year"

Автор книги: Gayle Forman

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

Thirty-one

The Donnellys, the family hosting tonight’s Seder, live in a large sprawling white stucco house with a makeshift soccer pitch out front. When we arrive, several blond people spill out the front door, including three boys who Yael has told me she can’t tell apart. I can see why. Aside from their height, they are identical, all tousled hair and gangly limbs and knobby Adam’s apples. “One’s Declan, one’s Matthew, and the little one, I think, is Lucas,” Yael says, not so helpfully.

The tallest one bounces a soccer ball in his hand. “Time for a quick game?” he asks.

“Don’t get too muddy, Dec,” the blonde woman says. She smiles. “Hi, Willem. I’m Kelsey. This is Sister Karenna,” she says, gesturing to a weathered old smiling woman in a full Catholic habit.

“Welcome, welcome,” the nun says.

“And I’m Paul,” a mustached man in a Hawaiian shirt says, bundling me into a hug. “And you look just like your mama.”

Yael and I stare at each other. No one ever says that.

“It’s in the eyes,” Paul says. He turns to Yael. “You hear about the cholera outbreak in the Dharavi slum?”

They immediately start talking about that, so I go play some soccer with the brothers. They tell me how they’ve been discussing Passover and the Exodus all week long as part of their studies. They are homeschooled. “We even made matzo over a campfire,” the smallest one, Lucas, tells me.

“Well, you know more than me,” I say.

They laugh, like I’m joking.

After a while, Kelsey calls us inside. The house reminds me of a flea market, a little of this, a little of that. A dining table on one side, a chalkboard on the other. Chore charts on the wall, alongside pictures of Jesus, Gandhi, and Ganesha. The entire house is fragrant with roasting meat.

“It smells wonderful,” Yael says.

Kelsey smiles. “I made roast leg of lamb stuffed with apples and walnuts.” She turns to me. “We tried to get a brisket, but it’s impossible here.”

“Holy cow and all,” Paul says.

“This is an Israeli recipe,” Kelsey continues. “At least that’s what the website said.”

Yael is quiet for a minute. “It’s what my mother would’ve made.”

Yael’s mother, Naomi, who escaped the horrors Saba had lived through only to be struck by a delivery truck on the way back from walking Yael to school. Universal law of equilibrium. Escape one horror, get hit by another.

“What else do you remember?” I ask hesitantly. “About Naomi.” She was another unmentionable when I was growing up.

“She sang,” Yael says quietly. “All the time. At the Seders too. So there was lots of singing at the Seders—before. And people. When I was a child, we had a full house. Not after. Then it was just us. . . .” She trails off. “It wasn’t as joyful.”

“So tonight, there will be singing,” Paul says. “Someone get my guitar.”

“Oh, no. Not the guitar,” Matthew jokes.

“I like the guitar,” Lucas says.

“Me, too,” Kelsey says. “Reminds me of when we met.” Her and Paul’s eyes meet and tell a quiet story, the way Yael and Bram’s used to, and I feel a longing pull at me.

“Shall we sit down?” Kelsey asks, gesturing to the table. We take our seats.

“I know I railroaded you into this again, but Yael, would you mind being the leader?” Paul asks. “I’ve been studying up since last year and I’ll chime in, but I feel you’re better qualified. Otherwise we can ask Sister Karenna to do it.”

“What? I do it?” Sister Karenna jerks up.

“She’s a little deaf,” Declan whispers to me.

“You don’t have to do anything, Sister, but relax,” Kelsey says in a loud voice.

“I’ll do it,” Yael tells Paul. “If you help.”

“We’ll tag-team it,” Paul says, winking at me.

But Yael hardly seems like she needs the help. She says an opening prayer over the wine in a clear strong voice, as if she’s done this every year. Then she turns to Paul. “Maybe you might explain the point of the Seder.”

“Sure.” Paul clears his throat and starts a long meandering explanation about how a Seder is meant to commemorate the Jews’ exodus from Egypt, their escape from slavery and their return to the Promised Land, the miracles that ensued to make this happen. “Though this happened thousands of years ago, Jews today retell the story every year to rejoice in the triumphant history, to remember it. But here’s why I wanted to jump on the bandwagon. Because it’s not just a retelling or a celebration of history. It’s also a reminder of the price and the privilege of liberation.” He turns to Yael. “That sound right?”

She nods. “It’s a story we repeat because it’s a history we want to see repeated,” she says.

The Seder continues. We say blessings over the matzo, we eat the vegetables in salt water, and then the bitter herbs. Kelsey serves soup. “Not matzo ball, mulligatawny,” she says. “I hope lentils are okay.”

While we’re eating our soup, Paul suggests that since the point of the Seder is to retell a story of liberation, we all take a turn and talk about a time in our lives when we escaped some sort of oppression. “Or escaped anything really.” He goes first, talking about his life as it used to be, drinking, drugs, aimless and sad before he found God, and then found Kelsey and then found meaning.

Sister Karenna goes next, talking about escaping the brutality of poverty when she was taken in by a church school, and going on to become a nun to serve others.

Then it’s my turn. I pause. My first instinct is to tell about Lulu. Because really that was a day I felt like I escaped danger.

But I decide to tell a different story, in part because I don’t think this one has been told out loud since he died. The story of one hitchhiking girl and two brothers and the three centimeters that sealed all our fates. It’s not really my escape. It’s hers. But it is my story. The founding tale of my family. And as Yael said about the Seder, it’s a story I repeat because it’s a history I want to see repeated.

Thirty-two

The night before I fly back to Amsterdam, Mukesh calls to go over all my flight details. “I got you an exit row seat,” he says. “You’ll be more comfortable, with all your height. Though maybe if you tell them you are a Bollywood star, you’ll get business class.”

I laugh. “I’ll do my best.”

“When does the film come out?”

“I’m not sure. They just finished shooting.”

“Funny how it all worked out.”

“Right place, right time,” I tell him.

“Yes, but you wouldn’t have been in the right place in the right time had we not canceled your camel trip.”

“You mean it got canceled. Because the camels got sick.”

“Oh, no, camels just fine. Mummy asked me to bring you back early.” He lowers his voice. “Also, plenty of flights back to Amsterdam before tomorrow, but when you disappeared to the movie, Mummy asked me to keep you here a little bit longer.” He chuckles. “Right place, right time.”

• • •

The next morning, Prateek comes to drive us to the airport. Chaudhary shuffles to the curb to see us off, wagging his fingers and reminding us of the legally mandated taxi fares.

I sit in the backseat this time, because this time Yael is coming to with us. On the ride to the airport, she is quiet. So am I. I don’t quite know what to say. Mukesh’s confession last night has rattled me, and I want to ask Yael about it, but I don’t know if I should. If she’d wanted me to know, she would’ve told me.

“What will you do when you get back?” she asks me after a while.

“I don’t know.” I really have no idea. At the same time, I’m ready to go back.

“Where will you stay?”

I shrug. “I can stay on Broodje’s couch for a few weeks.”

“On the couch? I thought you were living there.”

“My room’s been rented.” Even if it hadn’t, everyone is moving out at the end of the summer. W is moving in with Lien in Amsterdam. Henk and Broodje are going to get their own flat together. It’s the end of an era, Willy, Broodje wrote me in an email.

“Why don’t you go back to Amsterdam?” Yael asks.

“Because there’s nowhere to go,” I say.

I look straight at her and she looks straight at me and it’s like we’re acknowledging that. But then she raises her eyebrow. “You never know,” she says.

“Don’t worry. I’ll land somewhere.” I look out the window. The car is climbing onto the expressway. I can already feel Mumbai falling away.

“Will you keep looking for her? That girl?”

The way she says it, keep looking, as if I haven’t stopped. And I realize in some way, I haven’t. Which is maybe the problem.

“What girl is this?” Prateek asks, surprised. I never told him of any girl.

I look at the dashboard, where Ganesha is dancing away just as he did on that first drive from the airport. “Hey, Ma. What was that mantra? The one from the Ganesha temple?”

“ Om gam ganapatayae namaha?” Yael asks.

“That’s the one.”

From the front seat, Prateek chants it. “ Om gam ganapatayae namaha.”

I repeat it. “ Om gam ganapatayae namaha.” I pause as the sound floats through the car. “That’s what I’m after. New beginnings.”

Yael reaches out to touch the scar on my face. It’s faded now, thanks to her ministrations. She smiles at me. And it occurs to me that I might have already gotten what I asked for.

Thirty-three

MAY

Amsterdam

Aweek after I get back from India, while I’m still camped out at the couch on Bloemstraat trying to get over my jetlag and figure out what my next move is, I get an unlikely call.

“Hey, little man. You coming to clear your shit out of my attic?” There’s no introduction, no preamble. Not that I need one. Even though we have not spoken in years, I know the voice. It’s so much like his brother’s.

“Uncle Daniel,” I say. “Hey. Where are you?”

“Where am I? I’m in my flat. With my attic. That has your shit in it.”

This is a surprise. All the years I grew up, I have never actually seen Daniel in the flat he owns. It’s the same flat on the Ceintuurbaan that he and Bram used to live in. Back then, it was a squat. It’s where they were living when Yael came and knocked on the door and changed everything.

Within six months, Bram had married Yael and moved them into their own flat. Within another year, he’d cobbled together the funds to buy a broken-down old barge on the Nieuwe Prinsengracht. Daniel stayed in the squat, eventually getting a lease for it and then buying it from the city government for a pittance. Unlike Bram, who went on to fix up his boat, floorboard by floorboard, until it was the “Bauhaus on the Gracht,” Daniel left the flat in its state of anarchist disrepair and rented it out. He got almost nothing for it. “But nothing is enough to live like a king in Southeast Asia,” Bram used to say. So that’s where Daniel stayed, riding the ups and down of the Asian economy with a series of business ventures that mostly went nowhere.

“Your ma called,” Daniel continues. “Told me you were back. Said you might need a place to stay. I told her you needed to come get your shit out of my attic.”

“So I have shit in the attic?” I ask him, stretching out from the too-short sofa and trying to digest my surprise. Yael called Daniel? For me?

“ Everyonehas shit in the attic,” Daniel says, laughing a huskier, smokier version of Bram’s laugh. “When can you come over?”

We arrange for me to come over the next day. Daniel texts me the address, though that’s hardly necessary. I know his flat better than I know him. I know the stuck-in-time furniture—the zebra-striped egg chair, the 1950s lamps that Bram used to find at flea markets and rewire. I even know the smell, patchouli and hash. “It’s how this place has smelled for twenty years,” Bram would say when he and I would visit the flat together to fix a faucet or deliver keys to a new tenant. When I was younger, the lively multi-ethnic area where Daniel lived, right across from the treasures of the Albert Cuyp street market, seemed like another country from the quiet outer canal where we lived.

Over the years, the neighborhood has changed. The once working-class cafés around the market now serve things with truffles, and in the market, alongside the stalls hawking fish and cheese, there are designer boutiques. The houses have smartened up, too. You can see them through picture windows, the sparkling kitchens, the expensive clean-lined furniture.

Not Daniel’s place, though. As his neighbors renovated and upgraded, his flat dug into its time warp. I suspect that’s still the case, especially after he warns me that the buzzer doesn’t work and instructs me to call upon arrival so he can throw down the keys. So I’m caught a little off guard when he opens the door to the flat and I’m ushered into a lounge, all wide-plank bamboo floors, sage-colored walls, low, modern sofas. I look around the room. It’s unrecognizable, except for the egg chair, and even that’s been reupholstered.

“Little man,” Daniel says, though I am not little at all, a few fingers taller than him. I look at Daniel. His reddish hair is maybe a little shot through with gray, the smile lines cut a little deeper, but otherwise he’s the same.

“Little uncle,” I joke back, patting him on the head as I hand him back the keys. I walk around. “You’ve done something to the place,” I say, tapping a finger to my chin.

Daniel laughs. “Oh. I’m only halfway there, but that’s halfway farther than no way.”

“True enough.”

“I’ve got big plans. Actual plans. Where are my plans?” Out the window, there’s the roar of a jet rumbling through the clouds. Daniel watches it, then he resumes his search, spinning around peering at the crowded bookshelves. “It’s a little slow going because I’m doing the work myself, though I can afford to hire it out, but it just seemed like I should do it this way.”

Afford it? Daniel has always been broke; Bram used to help him out. But Bram’s not here. Maybe one of his Asian business ventures finally hit. I watch Daniel skitter around the room in search of something, finally locating a set of blueprints shoved halfway under the coffee table.

“I wish he was here to help me; I think he’d be happy that I’m finally making this place mine. But in a way I feel like he is here. Also, he’s footing the bill,” he says.

It takes me a minute to understand who he’s talking about, what he’s talking about. “The boat?” I ask.

He nods.

Back in India, Yael barely spoke of Daniel. I figured that they weren’t in touch anymore. With Bram gone, why would they be? They never liked each other. At least that’s how it seemed to me. Daniel was flakey, messy, a spendthrift—all the things that Yael loved in Bram in less extreme form—and Yael was the person who swept in and upended Daniel’s life. If there wasn’t much room for me, I can only imagine how it felt for him. It made sense to me why Daniel moved half a world away a few years after Yael showed up.

“There wasn’t a will,” Daniel says. “She didn’t have to do that, but of course she did. That’s your ma for you.”

Is it? I think about my trip to Rajasthan, an exile that turned out to be what I needed. Then I think about Mukesh, not just canceling the camel tour and delaying my return flight at Yael’s behest, but also dropping me off at the clinic that day, when everyone seemed to be expecting me. I’d always assumed my mother was so hands off, taking care of everyone but me. But I’m starting to wonder if perhaps I misunderstood her brand of caretaking.

“I’m beginning to get that,” I tell Daniel.

“Good timing, too,” he says. He scratches his beard. “I didn’t offer you coffee. You want coffee?”

“I wouldn’t say no to a coffee.”

I follow him into the kitchen, which is the old kitchen, all chipped cupboards, cracked tiles, ancient tiny gas range, cold-water-only sink.

“Kitchen’s next. And the bedrooms. Maybe halfway was a bit optimistic. I’d better get on it. You should come live with me. Help me out,” he says with a loud clap of his hands. “Your pa always said you were handy.”

I’m not sure if I’m handy, but Bram was always drafting me for help with some home-improvement project or another.

He puts the coffee on the stove. “I gotta get into gear. I’ve got two months now, so tick-tock, tick-tock.”

“Two months until what?”

“Oh, shit. I didn’t tell you. I only just told your ma.” His face breaks out into a smile that looks so much like Bram’s it hurts.

“Told her what?”

“Well, Willem, I’m going to be a father.”

• • •

As we drink coffee, Daniel fills me on the big news. At the age of forty-seven, the perennial bachelor has at last found love. But, because apparently the de Ruiter men can never do things the simple way, the mother of Daniel’s child is Brazilian. Her name is Fabiola. They met in Bali. She lives in Bahia. He shows me a picture of a doe-eyed woman with a lit-from-within smile. Then he shows me an accordion folder, several centimeters thick, his correspondence with the various government agencies to prove the legitimacy of their relationship so she can get a visa and they can be married. In July, he is going to Brazil in preparation for the birth in September, and, he hopes, the wedding soon after. All going well, they’ll be in Amsterdam in the fall, and return to Brazil for the winter. “Winters there, summers here, and when he is old enough for school, we’ll reverse it.”

“He?” I ask.

Daniel smiles. “It’s a boy. We know. We already have a name for him. Abraão.”

“Abraão,” I say, rolling it over my tongue.

Daniel nods. “It’s Portuguese for Abraham,”

We both are silent for a moment. Abraham, Bram’s full name.

“You’ll move in, help, won’t you?” He points to the blueprints, the one bedroom that will be made into two, the flat that once housed the two brothers, and for a spell housed all three of them before it was just Daniel all on his own. And then, not even him.

But now we are two here. And soon there will be more. After so much contracting, somehow, inexplicably, my family is growing again.

Thirty-four

JUNE

Amsterdam

Daniel and I are on the way to the plumbing supply shop to pick up a shower body when his bike gets a flat tire.

We stop to inspect. There’s a nail lodged deep into the tube. It’s four-thirty. The plumbing store closes at five. And then it’s closed for the weekend. Daniel frowns and throws his arms in the air like a frustrated child.

“Goddammit!” he curses. “The plumber’s coming tomorrow.”

We did the bedrooms first, a mess of studs and drywall and plaster, neither of us knowing exactly what we were doing, but between books and some old friends of Bram’s, we managed to make a tiny “master” bedroom, with a loft bed, and a tinier nursery, which is where I’m now living.

But the learning curve was high and it took longer than we’d expected, and then the bathroom, which Daniel thought would be simple—swapping out seventy-year-old fixtures for modern ones—turned out to be anything but. All the pipes had to be replaced. Coordinating the arrival of the tub and the sink and the plumber—another of Bram’s friends, who is doing the job on the cheap but also on his off hours, nights and weekends—has challenged Daniel’s already limited logistical skills, but he soldiers on. He keeps saying that if Bram built a boatfor his family, dammit, he’s going to build a flat for his. And it’s such a strange thing to hear, because I’d always thought Bram built the boat for Yael.

The plumber came last night, we thought, to finish the bath and shower installations, only to tell us he couldn’t install the new tub that had finally arrived until we had a shower body. And we can’t finish tiling the bathroom and move on to the kitchen—which the plumber said will probably also need all new pipes—until we have a shower.

For the most part, Daniel has approached the renovation with the sheer enthusiasm of a child building a sand castle at the beach. Every other night, when he and Fabiola Skype, he lugs his battered laptop around the flat, showing off all the latest modifications, discussing furniture placement (she’s big into feng shui) and colors (pale blue for their room; butter yellow for the baby’s).

But during those semi-nightly calls, you can see the bump is growing. After the plumber left, Daniel admitted he could almost hear the baby inside, ticking like one of those old alarm clocks. “Ready or not, here he comes,” he’d said, shaking his head. “Forty-seven years, you’d think I’d be ready.”

“Maybe you’re never ready until it’s upon you,” I’d said.

“Very wise, little man,” he’d said. “But goddamn it, if I’mnot ready, I’m going to have the flatready.”

“Go on ahead, take mine,” I tell Daniel now, swinging off my bike. It’s the same beat-up old workhorse I bought off a junkie when I first came back to Amsterdam last year. It stayed locked up outside Bloemstraat all those months I was in India, no worse for wear. When I started working on the flat, I brought it back to Amsterdam, along with the rest of my things, all of which fit on the bottom two shelves of the bookshelf in the baby’s room. I don’t have much: Some clothes. A few books. The Ganesha statue Nawal gave me. And Lulu’s watch. It still ticks. I hear it in the night sometimes.

Problem solved, Daniel is bright sunshine again. With a gappy grin, he hops onto my bike, and takes off pedaling, waving behind him, almost slamming into an oncoming moto. I wheel his bike off the narrow alley and turn onto the wide canal of the Kloveniersburgwal. I’m in an area sandwiched between the shrinking Red Light District and the university. I head in the direction of the university, more likely to find bike repair shops there. I pass an English-language bookstore I’ve ridden by a few times before, always somewhat curious. On the stoop is a box of one-euro books. I poke through—it’s mostly American paperbacks, the kind of thing I read in a day and traded when I was traveling. But at the bottom of the box, like a displaced refugee, is a copy of Twelfth Night.

I know I probably won’t read it. But I have a bookshelf now for the first time since college, even if it’s only temporary.

I go inside to pay. “Do you know of a bike repair place nearby?” I ask the man behind the counter.

“Two blocks down, on Boerensteeg,” he says, without looking up from his book.

“Thanks.” I slide over the Shakespeare.

He glances at the cover, then looks up. “You’re buying this?” He sounds skeptical.

“Yeah,” I say, and then by way of an explanation I don’t need to give, I tell him I was in the play last year. “I played Sebastian.”

“You did it in English?” he asks, in English, with that strange hybrid accent of someone who’s lived abroad a long time.

“Yeah,” I say.

“Oh.” He goes back to his book. I hand him a euro.

I’m almost out the door when he calls out: “If you do Shakespeare, you should check out the theater down the way. They put on some decent Shakespeare plays in English in Vondelpark in the summer. I saw that they’re holding auditions this year.”

He says it casually, dropping the suggestion like a piece of litter. I ponder it there, on the ground. Maybe it’s worthless, maybe not. I won’t know unless I pick it up.