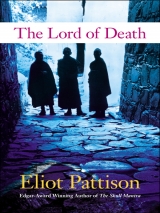

Текст книги "The Lord of Death"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

Jin turned away, lighting a cigarette as he surveyed the slopes. “Those monks could be a hundred miles away by now. Religious Affairs thinks I can just knock on a few doors and they will run out, begging me to put manacles on them.”

Shan glanced back at the shepherd boy, considering Jin’s words. A woman was pulling the boy backward now, tears staining the soot on her face. “Your assignment is for Religious Affairs? Not Cao? Not Public Security?”

“The Bureau of Religious Affairs has jurisdiction over monks. After all the protests last year, the policy is for Public Security to keep a low profile with monks and lamas, especially in this area, so they loan men to the bureau and put them in neckties. And Religious Affairs is taking this personally. The fire, then the ambush. Someone betrayed them, someone shamed them.”

“What fire?”

“Two days before the murders, in town. The Religious Affairs office was nearly burned down. Officially they say it was an accident. But the unofficial version is different. They found something in the fire, a statue of an old protector god that didn’t belong there, sitting in the ashes, unharmed. Like the god had decided to take revenge after all these years.”

Shan’s mind raced. Since the last season of protests in Tibet the government had grown unpredictable in reacting to anything that might hint of political unrest. More than ever, Public Security worked in the shadows. It would have worked especially hard to assure no one suspected an overt act against Religious Affairs. “What kind of deity?” he asked.

Jin grimaced, as if Shan were trying to trap him. Displaying such knowledge in some circles would show dangerous reactionary leanings. “The mother protector, Tara. Not like at the killings.”

Shan went very still. “There was a deity at the murder scene?”

Jin frowned. He clearly had not intended to divulge so much. “On a high, flat rock a hundred feet away, found the next day, looking at the crime scene. The head of a bull, holding a rope and sword,” he explained.

“You mean Yama the Lord of Death.”

As if to change the subject, Jin reached into his pocket and produced a heavy steel carabiner, the snaplink model favored by climbers on the upper slopes. “They think I can find a trail of these that will lead me to the traitor.”

“A trail of snaplinks?”

“Someone handed these out to shepherds and farmers in the upper valleys, like favors or souvenirs. They must have been stolen, like those ropes that were used in the ambush.” As he spoke, the handheld radio in his vehicle crackled to life with a report that the town of old Tingri, forty miles away, had been searched with no sign of the fugitives. Jin muttered a curse, then reached in and shut off the radio. He hated being accountable to anyone else when he was outside the office.

The woman appeared on the slope above the house, frantically running with the boy toward their pastures. “Did they have one of the snaplinks?”

Jin shrugged. “You know these hill people. They won’t talk to anyone in a uniform. I said I’m coming back tomorrow to shoot ten sheep if they don’t tell me where I can find those monks.”

“But you won’t.”

The constable shrugged again. “I am fond of mutton.”

“They’ll spend the day moving all their sheep. Come back tomorrow and you’ll find no trace of the sheep or the shepherds. And shepherds don’t go anywhere close to the base camp, there’s no grass that high up. You need to look in town or in the base camp itself.”

“I don’t get paid to concoct theories. Someone’s coming from Lhasa for that. A real wheelsmasher. He’ll start with the other small gompas, assuming monks help each other.”

Shan’s mouth went dry. A wheelsmasher was one of the senior zealots from the Bureau of Religious Affairs, notorious for crushing old prayer wheels under their boots. A wheelsmasher team had come through the month before, removing all public statues of Buddha. “I need to see Tan,” he said again, more urgently.

“We used to have a captain from Shanghai who kept a pack of those big Tibetan mastiffs, the ones they say are incarnations of failed monks. He would cruise along the roads and shoot a stray one, then skin it and feed it to his pack. He could never stop laughing when he watched, telling everyone it was the story of modern Tibet. Dog eat dog. That’s what you are to those who are running the jail now. Fresh meat. It’s not the county’s jail anymore. It belongs to Public Security until this is over.”

“They have to eat. They have to have their toilets cleaned.”

“Meaning what?”

“Meaning they still rely on your office to assure the dirty chores get done.”

Jin’s silence was all the confirmation Shan needed. “Just get me in with the cleaning crew. Today. This evening.”

Jin studied Shan with a new, appraising gaze. “If I don’t find those monks soon,” he offered in a tentative tone, “Religious Affairs will have me on my hands and knees looking under every pile of yak dung.”

Shan clenched his jaw, gazed for a long moment at the snowy peak above them. “I will share what I learn about the ambush. You share what you know about the killings. But I will not help you find the monks.”

“Not good enough. This is my one chance at a victory big enough to get me out of this damned county.” The week before, Jin had stopped Shan on the road and asked him to look over his application for a transfer to one of the cities in the east. More than once he had dreamily spoken of living in Hong Kong, or even Bangkok.

“I can help with your relocation,” Shan stated flatly. “I can do it today.”

Jin’s face tightened. “What the hell are you talking about?”

“I’ve been to the desert in Xinjiang,” Shan observed, referring to the vast province north of Tibet, a favorite dumping ground for disfavored government workers. “The sand is always blowing. It gets in your nostrils, in your mouth, in your clothes, in your rice. In the summer it can be hot enough to boil tea. Once I saw a man’s eyeballs roll up into his head and he dropped dead from the heat. In the winter people who stop to sleep in their cars are usually found frozen to death. After a month there you will think this is paradise.”

Jin fidgeted with the pistol on his belt.

“I will go back to town now,” Shan said. “I will find Major Cao and give him a signed witness statement that you were near the crime scene, right there when those monks escaped.”

Shan watched for a reaction, confident in his assessment of Jin.

“You don’t know that.”

“You heard the guns and you went to investigate. But as soon as you saw all the knobs, you fled. An armed officer on a horse could have rounded up those monks, and maybe the murderer as well. Religious Affairs and Public Security will fight over the right to interrogate and then punish you. Every other law enforcement officer known to have been there has already been shipped to the desert, or worse. How long before you’re breathing sand into your lungs? A week? Three days? I don’t think they even gave the others time to pack.”

“Cao will eat you alive if he finds you with his prisoner.”

“Me? Men like Cao have tried more than once.” Shan studied Jin’s anxious face, then shrugged and turned back to Jomo, waiting in the truck. “Don’t forget the sunscreen,” he called out. “You’ll need barrels of the stuff where you’re going.”

An hour later Jomo eased the truck to a stop by the curb in the center of Shogo town, shaking Shan from the slumber that had overtaken him on the long descent from the high ranges.

“Wait five minutes,” the Tibetan instructed as he climbed out. “Then I’ll take you back to the stable.”

Shan watched the mechanic uneasily as he disappeared behind the door of the familiar two-story building, then climbed out to stretch his legs, pacing past the signs that advertised Tsingtao beer and karaoke, stepping to the corner where he could see the squat gray complex that housed the jail. In his mind’s eye, before turning back and entering the tavern, he constructed where Tan’s cell would be.

Gyalo’s inn was the most popular place in town after working hours, filled not only with townspeople but also the truck drivers who used Shogo as an overnight rest stop on the route to Nepal. Cigarette smoke hung heavy in the dimly lit room, laced with the smell of unwashed bodies and the raw onions that patrons chewed on like apples between swigs of pungent sorghum whiskey.

The customers hooted and whistled as a wiry old man in a red robe danced along the top of the bar, waving the robe provocatively. Jomo had come to see his father but he just stood in the shadows, staring in shame at the floor. Drunken customers were tossing coins at his father. The robe he wore, covered with bumper stickers, souvenir button pins and sewn patches meant for army uniforms, was intended for a Buddhist monk. Jomo’s father, the town jester and keeper of the tavern, had been a member of Shogo’s monastery before it was leveled decades earlier.

Shan followed Jomo into the shadows, though a moment too late.

“Demons!” Gyalo cried jubilantly as he pointed at them, his voice slurred from drink. “Fresh demons have arrived!” With astonishing speed he picked up an empty beer bottle and threw it at Shan. It would have hit him squarely in the head had he not sidestepped. The crowd went wild, raucously cheering at the new show.

“We should go,” Jomo muttered, not lifting his gaze from the floor. He looked as if he were about to weep. “I’ll come back when he’s sober.”

As they began to move toward the door, Gyalo pranced across two tables to alight on a heavy wooden chair mounted on an ornate altar salvaged from a temple destroyed years earlier. On the back of the chair a T-shirt was stretched, with the image of a woman making love to a skeleton dressed as a pirate. On the wall to the left, an image of Buddha as a rock star had been painted, on the right was another Buddha on a motorcycle, a cigarette dangling from his lips. Beneath it was a large bronze deity in the meditation position, an antiquity, its hands pocked where cigarettes had been extinguished, its lap now an ashtray.

Hands reached out and grabbed Shan and Jomo, pulling them toward the altar. Shan struggled at first, knowing what was to happen, but it was futile to resist. He let himself be manhandled into a standing position next to Jomo, beneath Gyalo.

“Gulag prisoner!” Gyalo shouted, lifting his cup to salute Shan. “We worship at your feet!” He drank, then lowered his voice to a stage whisper, addressing the crowd. “He never speaks of what crime he committed to be condemned to Tibet. Mass murder maybe? Drug lord? Raped the Chairman’s sister?” Shan did not resist as the old Tibetan, not for the first time, lifted Shan’s arm and rolled down his sleeve to display Shan’s tattoo for all to see. “Marked by the gods!” he cried, and poured the remaining contents of his cup over the tattoo as if to anoint it.

Jomo spat a curse at his father, grabbed Shan’s arm, and pulled him from Gyalo’s reach. His father sneered at Jomo, then broke into loud, howling, wheezing laughter that quickly spread through the room. “ Pum phat!” Gyalo shouted at their backs. They were old words, used as an emphasis at the end of certain prayers.

“Why do you let him do that?” Jomo demanded as they stepped outside.

“He’s just trying to sell more drinks.”

“He’s trying to get rid of you. He knows that the more people who know you are a convict the less safe you are.”

Shan studied Jomo’s face, which had become tormented at Gyalo’s mention of rape. His father had been a young lama, had taken his vows of celibacy, when the town monastery had been destroyed. For some reason, he had been singled out for a special punishment used to break monks and build a new breed for Tibet. A female Chinese soldier had been ordered to become pregnant by him. Jomo had never known his mother, only that she had been one of the Chinese invaders and had forced Gyalo to surrender his robe by giving him a son.

“Why did you go in there?” Shan asked as Jomo coaxed the aged truck to life.

“He left me a note this morning. He said he urgently needed to know everything about those murders.”

The cleaning crew assigned to the constable’s office performed its chores after the supper hour, entering in the dark through the rear door under a guard detail that Jin had decided to supervise. Shan kept his head low, half concealed by a mop. Fighting a terrible, nearly paralyzing fear, he worked his mop toward the metal door that marked the corridor of holding cells, sliding the bucket forward with his foot. The heavy door was locked when he reached it. Suddenly an arm extended past his shoulder with a key. Constable Jin blocked Shan’s passage as the door swung open, gesturing forward a gray haired woman, clutching two empty plastic buckets, who advanced with a businesslike air. The constable stood guard at the door, glaring at Shan as he went through the motions of cleaning a row of benches along the adjacent wall. Moments later the woman reappeared, expressionless, her buckets now filled with stained rags, splinters of wood, and other debris from the interrogation rooms. Jin held the door for Shan, escorted him to the cell at the end of the corridor and opened it.

“If he takes one step outside this cell,” Jin hissed, “I will shoot you both.”

The cell, still reeking of blood, vomit, and ammonia, had changed little since Shan left it. The blood soaked pallet had been replaced, the stains scrubbed from the floor, replaced by new ones, the piles of rags had been tossed against the back wall. Only one of the filthy piles was Colonel Tan of the People’s Liberation Army, the dreaded tyrant of Lhadrung County.

Shan turned and confronted Jin with a silent, expectant gaze.

“Fuck your mother,” Jin spat, then spun about and retreated to the door at the far end of the corridor.

Tan, either unconscious or sleeping, was slumped against the wall, his body convulsing every few moments– the aftereffect, Shan well knew, of electroshock. Shan did his best to clean the filthy tin cup at the sink, filled it from a bucket of water and bent to Tan. When he touched the colonel’s shoulder, Tan reacted as if he had been struck, jerking away with a groan, his upper body slowly falling toward the floor, lacking the strength to right itself.

Shan cradled Tan’s head against his leg and dripped water over his split, bloodied lips. After a moment the colonel reacted with another groan. His eyelids fluttered, struggling to open, then he gave up and lost consciousness. Shan dripped water over his head. Then with a wet rag he wiped the blood from Tan’s face, tied another rag over an oozing wound on his temple, and inspected the bloody ends of his fingers. Shan thought of running to the interrogation room for a medical kit but realized the knobs would raise unwelcome questions when they discovered their prisoner in bandages. Tan’s feet were bare, badly bruised.

Beating the soles of the feet was a trademark of older interrogators, used widely by the gangs of Red Guards who had terrorized the country a generation earlier. The fingers of Tan’s left hand twitched; on his forearm Shan found the telltale marks of two electrode clamps.

He found himself murmuring the manimantra, the prayer for the Compassionate Buddha, as the lamas in his prison had done when they first cleaned his own interrogation wounds, years earlier. Tan’s eyelids fluttered again and stayed open this time, eyes still unseeing. Shan held the cup to his lips and he drank.

After draining the cup, Tan breathed deeply, rolled his head toward Shan, and recoiled in horror, jerking himself upright, lashing out with a hand to slap Shan’s cheek with surprising force.

“ You!” he snarled, and mustered enough strength to kick at Shan, flailing the air with his feet, until he collapsed against the wall again with an agonized groan. He seemed to regard Shan’s presence as a new form of torture.

“The old lamas taught me a trick,” Shan said in a low, steady voice, “for when the pain gets unbearable. Hold your breath as long as you can and count. When you breathe again, start over. Just focus on breathing and counting.”

“You have no right!” Tan spat. His voice was hoarse but its fury was unmistakable. His face narrowed in confusion. “How could you possibly know? How could you possibly be here?”

“Have you forgotten this is where the medical prison is you transferred my son? I assumed you did it to get rid of me, knowing I would follow.”

A battle raged behind Tan’s black pupils. The animal the knobs had reduced him to fought with something else, the brooding, conscious thing that had been pushed deep inside. His eyes glazed then brightened, then glazed again before a hard, familiar gleam returned to them. “I sign papers for the transfer of dozens of recalcitrant prisoners. I can’t be expected to remember every parasite who transits through my county.”

It was a lie, they both knew, for Shan and Ko had presented persistent headaches to Tan in Lhadrung. “You use the present tense. I admire your optimism.” Shan rose and filled the cup again. As he extended it Tan knocked the cup away with a violent sweep of his arm.

“If they knew who you were, Shan, you’d be in the next cell. Get out or I’ll tell them.”

Shan silently retrieved the cup, filled it again and set it on the stool just beyond Tan’s reach.

“I was there, Colonel, minutes after the murderer left. They found me soaked with one of the victims’ blood. For a few days I was their favorite solution. Then I told them how to find the gun.”

Tan’s eyes flared. For a moment it seemed he was summoning the strength to leap at Shan. He was ten years older but he was all sinew and bone.

“They have only just begun on you,” Shan explained. “You know how it works. They are rewriting the script so they will know exactly what song they need you to sing. Tomorrow or the next day you’ll start seeing new faces, new devices, probably a doctor or two from the prison clinic. It’s what we used to call a half-moon case.”

Tan spat out blood, then with a finger probed the teeth of his upper jaw. “Half moon?”

“A case of vital political implications. It is too inconvenient to have it linger. Worse, it is politically embarrassing. Beijing will insist it be closed in two weeks. And one is already gone.”

“I don’t want your damned help. Go find one of your Tibetan beggars to coddle.”

“I predict a closed trial. Then they will take you to somewhere private, maybe just the cellar of this building, though I rather expect it will be somewhere remote up in the mountains. You will face a small group of senior Party members, probably a general or two. An officer young enough to be your grandson will sneer at you a moment, then slowly draw his pistol and put a bullet between your eyes.

“By the end of the month there will be a new colonel in your office in Lhadrung. All those photos of you on maneuvers, commanding brigades of tanks and missile batteries, presiding over National Day celebrations at town hall– they will take them and burn them. I recall you kept personal journals of your illustrious career. Toilet paper is in short supply. They will probably take your journals to the prisoners’ latrines. The last evidence of your existence on earth will be wiped on the backside of a starving Tibetan monk.”

“Get out!” Tan spat. A thin rivulet of blood spilled down his chin.

Shan looked up at the window high on the back wall, noticing for the first time the crimson splotches on the reinforced glass, then glanced at Tan’s bloody fingertips. The colonel, incredibly, had been climbing up, trying to break the window. “When they stop the torture,” Shan continued in a matter-of-fact tone, “that’s when you know it’s over. They will give you two days to heal, to be cleaned up. When the barber comes, you’re a dead man for certain. They want you to be able to stand up straight, clean and trimmed, ready for final inspection, before they eliminate you and everything you ever touched.”

The light faded from Tan’s eyes. His gaze shifted past Shan and settled on Constable Jin at the end of the corridor. “So you bribed a guard so you could gloat?” Tan muttered. “Maybe take a picture to share with your Tibetan friends in Lhadrung?”

“I came because you are innocent.”

Tan’s eyes turned back toward Shan, though his stony expression did not change. “You don’t know that.”

“Colonel, if you had murdered a minister of the State Council you wouldn’t have run, wouldn’t have tossed away your gun. You would have sat there and waited and berated the arresting officer for his dirty boots.”

With obvious effort Tan pushed himself up against the wall, high enough to grab the cup of water from the stool and gulped it down. His hand began twitching again. He seized it with his other hand, squeezing until the knuckles were white. “I’m not one of your pathetic lamas. I don’t want your pity. I don’t want the help of the likes of you.”

“When was your gun stolen? At the hotel? Have they asked you about the Western woman? Have Western investigators arrived?”

Tan pushed against the wall harder, until he could stand. He staggered a moment then straightened, the ramrod-stiff soldier again. He pulled off the rag Shan had tied around his head and threw it at Shan’s chest. He took a single step forward, raised a battered, bloody hand, and with a powerful blow hit Shan on the chest so hard he was slammed against the bars of the cell door.

“Guard!” Tan shouted toward Jin. “This lunatic has breached security! Get him out! He endangers your murderer!”

Jin led Shan out of the building with a victorious gleam in his eye, leaving him alone on a corner under one of the town’s few streetlights. Shan sat on the curb and stared at the fresh stain on his shirt. Tan’s blood.

Gradually he became aware of someone hovering near the edge of the pool of light. It was a teenage Tibetan, wearing one of the red T-shirts Tsipon gave to his porters, his features tight with fear. It seemed to take all of Shan’s strength to gesture him forward.

“It’s Tenzin!” the porter exclaimed in a terrified whisper. “Kypo said to find you. Tenzin’s ghost was seen in the village, doing the work of Yama the Lord of Death.”