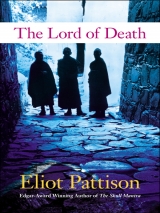

Текст книги "The Lord of Death"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

“I’ve been trying to make you understand, Yates. You and I are after the same thing. It is all about something that happened decades ago.”

Yates cast an uncertain glance at Shan, then his gaze went back to the symbol on the glass. “Kypo says you’re like a magnet to knobs. I can’t afford any more trouble.”

“Just take a walk with me.”

“Where?”

“Up to see your father.”

The two men did not speak as they climbed toward the top of the high ridge that curled around Tumkot. Yates, like Shan, no doubt recalled the last time they had been on the trail, assaulting each other in the moonlight as Yates carried his sack of little gods down the mountain.

The American slowed as they approached the ruined shrine, lingering behind. More than once Shan paused to look back and see Yates stopped, gazingly longingly toward the peak of Everest, visible in the distance. As he reached the shrine Shan halted, kneeling at a crumbling wall of lichen-covered mani stones, restacking and straightening the wall as the American approached with hesitant steps. Yates’s countenance held caution, perhaps even fear, but there was also a hint of shame as he glanced at the altar where he had removed the ancient figurines. “I will bring them back,” he said of the little gods he had taken. “I was always going to bring them back.”

He knelt beside Shan and silently assisted him with the stones, cleaning the faces inscribed with prayers, handing them to Shan for restacking.

After several minutes Shan stood. “I know some Tibetans who have a different way of speaking when they are at these shrines. There are words for addressing old gods that most younger Tibetans don’t even know, special prayers, special prostrations. I felt uncomfortable coming to such places at first, like an outsider or worse, like one of those who had caused the destruction. Then a monk took me to a patch of flowers that were bent beneath some stones fallen from a crumbling altar. He told me to remove the stones and replace them in the altar. When the flowers had straightened he said ‘Now your reverence is mingled with all the reverence that came before, which makes the shrine as much yours as mine.’” Yates searched Shan’s face as if trying to understand, then knelt and restacked a few more mani stones as Shan stepped to the altar under the overhanging ledge.

“This place has nothing to do with my father,” Yates declared, challenge in his voice. “If you think you can trick me into-” His complaint faded as he followed the finger Shan pointed toward the end of the altar. The crucifix was still there, in the dust of the altar, where Shan had left it days earlier.

The American’s hand shot out to grab the silver cross, then hesitated, lingering in the air. There was no question in Yates’s eyes, only a torrent of emotion. When he finally lifted the cross, he cupped it in both hands, as though it might crumble. He brought it out into the sunlight, studying it in silence as he dropped onto the remnants of a stone bench.

“I’ve seen it in a photograph,” he explained in a stunned voice.

“That last year he was at home, when I was two years old, there was a photo taken of me in his arms with my hand wrapped around the chain that held this.” He looked up with an intense gaze, searching the clearing. “I don’t know what it means, finding it here. This could have just been planted here last week.”

“No,” Shan said. “It’s been there for decades. You can see its shape imprinted in the layers of dust. It was there before most of the Yama statues.”

“Impossible,” Yates muttered. But he was arguing with himself, not Shan. He kept turning the cross over and over in his hand, examining every surface, as if expecting it to somehow divulge its secret. And it did speak to him, for after a moment he pointed to a small set of letters inscribed on the reverse of the cross. “SRY,” he declared in a voice that cracked with emotion, pointing the letters out to Shan. “My father’s initials. Samuel was his name.” He fell silent for a long moment. “ Tuchaychay,” he said, expressing his gratitude in Tibetan. “I owe you.”

“What you owe me is the truth.”

When Yates did not reply, Shan rose and gestured to the figurines remaining on the altar. “You owe it to them as well. You need to explain to these gods the real reason you came to them as a thief in the night, why one of them was lost over this cliff.” He extended his hand toward Yates, palm open. “Only the truth can be spoken in front of them.”

The American understood. He dropped the crucifix into Shan’s hand, glanced uneasily toward the altar and paced around the clearing in silence, pausing to clean and stack half a dozen more mani stones as Shan waited at the old bench. At last Yates rose and sat before the altar, looking at each of the gods in turn, as if silently greeting them.

“I used to do jigsaw puzzles of medieval paintings with my aunt and uncle who raised me,” Yates began. “Hundreds of pieces with shades of gray and brown, with a few patches of brilliant color. They made sense only if you kept the complete picture in mind as you worked. My father was always like that to me. I had only fragments to work with, and never had an image of the man as a whole. My aunt and uncle would speak of him with the same sound bites, never changing. A good, honest man. A great athlete. A lover of freedom. A fantastic aviator.”

“Not a scientist,” Shan observed.

“Not a scientist,” Yates admitted. “Once I heard my aunt and uncle talking about him with an older cousin. They were angry at him, said he could have come back and had a rich career as a pilot with the airlines. None of that made him alive for me. I wanted to know the sound of his laugh, wanted to know what was in his heart, to know the words he would have used to put me to bed if he had ever returned. They kept secrets about him, I knew that. Once when I was nine they were away and I found a shoebox hidden in their bedroom closet filled with letters and photos. There was a cloth pouch with little rolled up papers, only an inch wide, each tied with strips of leather. I had no clue what they were, just some strange adult thing. They frightened me somehow. They had an Eastern scent, incense I learned later. The paper was different, like it was handmade. The letters were tiny, in tiny handwriting.

“The early letters, the normal letters, were mostly to my mother. They looked like they had never been touched by her. I don’t think they were ever delivered to her, because she divorced my father a year after I was born and my aunt and uncle never spoke to her. I took a few and kept them under my mattress, reading them over and over. He wrote to her about a place called Camp Hale, hidden in some mountains somewhere.

“Whatever he was doing was a big secret. He kept saying it was very important and someday he would explain everything. What he did speak of made it sound like he was a professor. My students have come along faster than anyone expected, he would say, we are finished with our first round of classes and everyone passed with flying colors. But it was a strange kind of school. Sometimes it sounded like he was a student himself, saying he had finished his course in winter survival and was moving on to navigation and language.

“The more I asked, the less my aunt and uncle wanted to talk about him, as if he was some kind of mistake, which meant I must be some kind of mistake. I began to get angry at them. I took the shoebox out of their room and hid it in the attic. I took the cylinders of paper to a secret place I had up on the mountainside above the house and read them all. In them my father wrote about being in the Himalayas, about the wonderful people he was meeting. He drew little pictures in the margins. Some of strange churches with steeples like upside down ice cream cones. Shaggy cows with long horns. I opened another, and another. He asked about me in every note, kept saying the mission was going well. I couldn’t understand any of it. The notes scared me. Finally I got my nerve up and dropped one on the dinner table. My aunt became very angry and wouldn’t answer my questions. She said there was no need to drag up that rotten history. My uncle just became sad. Later he told me that his brother, my father, had sent a note mailed by someone else, from a city in India. In it he said he had found a way to send messages back that would be safe, that he would send bronze statues of a god called Yama, that the people who made them used the hollow compartment inside it to hold prayers and things. When the statue came my uncle was to cut open the base or loosen its solder with heat and he would find letters inside, wrapped up like the prayers that usually went inside. My father said that he was sending them because if something happened to him he wanted his son to know of the good work he was doing, of how important it was for the world. He said he would send a statue every couple of months, because he was allowed to send gifts home but letters were always censored.

“I couldn’t really understand. It seemed like my father was a prisoner in India. I heard my aunt telling someone that my father had become addicted to the drugs grown there and dropped out, then died in some alley in Calcutta. My uncle got angry at my aunt and said my father was no drug addict, just a good soldier.” Yates looked down at the ground for a moment, seeming overwhelmed by his memories. Shan gave the crucifix back to the American, who closed his fist around it and pressed it to his heart.

“So there I was, eleven years old and as confused as ever. My father was an addict, he was a soldier, a pilot, a professor, a prisoner, a mountain climber. I would have dreams about him, but he was always in shadows. No more of the statues ever came after the first, my uncle told me. But he gave me one more thing, a letter from the Army sent to him as next of kin. My father had been killed in the service of his country, it said, and he was being awarded a medal for bravery. The circumstances of his death did not permit recovery of his body. I didn’t know what else to do, where else to turn for the truth. I put the letter in the shoebox and didn’t open it again until I was years out of college. That’s when I noticed something in that letter from the army, a printed line at the top that said Office of Special Operations. I began writing my own letters to the government. It was a slow process. I had my business to worry about, running a sporting goods store first, then my trekking and climbing business. I married and got divorced. But I kept writing letters, to the army, to senators, to the veterans’ office. The few responses I received said all the files on the matter were classified, top secret. Eventually I found out Camp Hale was high in the Colorado mountains and I went there, at least to the nearest town. The people there said it had been used for radioactive testing so everyone stayed away from it.

“Then five years ago the files were declassified,” Yates continued, “and made available to the public.”

“Camp Hale,” Shan suggested, “had nothing to do with atomic tests.”

“Camp Hale was the only facility in the army that came close to a Himalayan habitat. It had been used as a training ground for mountain commandos in World War Two. The army loaned it to Special Operations, what later became the Central Intelligence Agency. A small group in the American government was formed for the purpose of supporting Tibetan independence. They brought in Tibetan resistance fighters to teach them English, survival training, navigation, radio operation, parachute jumping. It was so secret the Tibetans didn’t even know where they were. That’s what my father was doing, training the resistance. Eventually a base for the resistance army was set up in Nepal, along the Tibetan border. I finally received my father’s service records. They showed that after a year at Hale he asked to be transferred to Nepal, with the fighters he had trained.”

Yates stood and paced along the altar. “After that everything gets murky. Officially, Americans never crossed the border, except on air missions at night to drop Tibetans and supplies, sometimes hundreds of miles inside Tibet. Officially, my father was stationed at the base in Nepal the whole time. Officially, he was on a plane that never returned. But eventually I tracked down some of the other Americans involved, old men now, all retired. To a man they insisted no plane was ever lost, and several had known my father, said he was a great climber, that he fervently believed in what they were doing for the Tibetans. Not one would say anything about what happened to him. But when one of them, a pilot who still had a map of Tibet on the wall, discovered I was leading climbing expeditions onto Everest, he opened an old file and wrote down a series of numbers for me.”

“Map coordinates,” Shan said with a rush of realization. He unconsciously touched his pocket with the paper on which he had transcribed the numbers Yates had hidden in his cot.

“All within a hundred-mile radius of Everest. A preferred location because the Chinese air bases were far removed from this area, and the Chinese planes couldn’t handle the wild winds off the mountains.” Yates paused, gazed again at the row of silent Yamas as if waiting for them to speak.

“You think he came across, against orders, parachuting in with the Tibetan fighters.”

Yates nodded. “I am certain of it. I know it in my heart. And now you proved it with this cross.”

“Megan Ross knew about your father.”

“We were close friends. More than friends once. She found me with those old letters and we started talking-she loved the intrigue. It became a project for her. She helped me find some of the drop points.” He reached into a pocket of his parka and extracted a small handheld device. A cell phone, Shan thought at first, then the American turned its face toward him. “Global positioning. When the right satellites are overhead it tells your exact longitude and latitude.”

Shan remembered the pieces of the device he had found at the crime scene. “Megan had one,” he suggested. “And you were in a barley field with this one.”

Yates flushed with embarrassment. “I didn’t mean to damage the crops.”

“What did you expect to find at the drop points?”

“I don’t know. Anything. Maybe they died jumping, maybe I would find bones. Maybe one of them would be a place where some of my father lingered, left something of himself. It was the only hard evidence I had, that list of coordinates.”

“And the sign of the hammer and lightning.”

Yates nodded again. “It was drawn on one of those little rolled letters from my father, where he spoke of a new enemy arriving. A couple weeks ago I showed it to Megan, and she drew a copy of it, said she would ask some of the old Tibetans about it.”

“Suppose she did ask some old Tibetans about it. Not long after, she stepped into the car with Minister Wu.”

“Surely they are not connected.”

“You tell me. You knew why she went with the minister that day.”

“No. Yes. I don’t know. We were going to meet, to wait up the road together and intercept the minister’s car so we could have a private conversation about Wu’s development plans. But Megan never showed up that morning. I figured she got some other ride.”

“What she got was a book,” Shan said, “a book she stole from the library in town.”

“A book?”

“It had photos of the leaders of the Red Guard unit that had destroyed all the local temples and gompas, and killed the local monks.” Shan pulled out the photo he had taken from the library and handed it to the American. Yates gasped as he saw the crossed lightning and hammer; his jaw dropped as Shan pointed to the woman at the center of the table.

“It can’t be!”

“Megan was helping you with your project but she had another project that was even more important to her, her Himalayan Compact. This photo, or one like it, provided Megan the preemptive strike she needed. The book had long ago been removed from the library, may even have gotten the prior librarian killed. But the new librarian is a fanatic about having a complete collection. She tracked down what may be the only remaining copy this year. Megan was there in the library, reading it, the day before the murder. That’s when she discovered that Minister Wu had been the commander of the Hammer and Lightning Brigade.”

Yates’s face darkened with despair. “The fool. She should have told me.”

“Wu is a common name. There is no reason that people would have connected the minister to the Red Guard who used to be in Shogo. If people here knew Wu had been the head of the Brigade she would have been totally discredited in the region, her reputation destroyed in the international community she wants to attract. It was Megan’s bargaining chip. But Megan didn’t know the minister had a gun. Wu was as relentless today as she was forty years ago. Megan thought she was going to change Wu’s mind about her new campaign. But Wu would have known it meant the destruction of her career.”

“Surely the minister didn’t kill Megan.”

“There was no sign of a struggle, by either of them. I think Wu did not protest when Megan was shot, may have done it herself. But someone else was there, who was given the gun by Wu.”

“Given?”

“There was no sign of a struggle,” Shan said again. “She handed the gun to the third person, who promptly shot her too. I think the photo got both of them killed.”

“But what does my father. .” Yates began in confusion.

“Megan was at the library because of your father, she thought she might learn more about the resistance fighters in the region. She never expected to find that photo. But when she did, it changed everything for her. No doubt she was going to give it to you but first she was going to use it against Wu.”

They sat in silence a long time, Yates gazing at the altar, fingering his father’s cross, Shan at the outer edge of the clearing, by the cliff. He too had not fully digested the truth. He let the ice-scented wind scour him, peeling away his misconceptions about the murders. There was no mystery in events, his old friend Lokesh had once told him, only mysteries of the people involved. Like many Chinese, every Tibetan he knew had grown a hard, impenetrable shell around memories of the Cultural Revolution, around the years when the Chinese had cleansed the land of all resistance. But Shan knew now that it was in that black, inaccessible place where the truth would be found.

Chapter Thirteen

Yates would not leave the shrine without searching every inch of the ground, hoping for some further sign of his father. Shan helped for a few minutes then sat on the stone bench, extracting the notepad from his pocket, and began writing events and dates, one line at a time in English, starting with the Religious Affairs office burns down, Tenzin murdered at the advance camp, Tan loses pistol, murder of Minister Wu, Director Xie killed, Gyalo attacked in Shogo.When Yates appeared at his side, finished with his futile search, Shan extended the notebook.

“What’s this?” the American asked.

“A wise man once said that if the true face of a mountain cannot be known, it is because the one looking at it is standing in its midst. I want to trade, what I know for what you know. I want you to look at what I know, because I am standing in its midst.”

Yates cast a skeptical glance at Shan, shrugged, then went to his backpack and extracted a tattered nylon pouch. He accepted the pad from Shan then emptied the pouch onto the bench. Several old letters, the photos Shan had seen at the base camp, a map, copies of pages from a book, a printed form.

The two men sat in silence for several minutes, Yates flipping pages in Shan’s notepad, writing his own notes. Shan read the form, an official copy of the military service record for Captain Samuel Yates, then the letters, which were nothing more than what Yates had already explained. The copied pages contained a description of Camp Hale from some annal of the Cold War, recounting how a small group of elite intelligence operatives and military experts had created a miniature world for Tibetan trainees in the Colorado mountains, teaching them about Western history, introducing them to hot dogs and hamburgers. The pages from the book included photos, showing American men in uniforms without insignia, some with pipes or cigars in their mouths, others with white khata offering scarves around their necks, traditional Tibetan offerings of friendship. There were a few quotes from some of the participants, recorded years later, reflecting deep admiration for the Tibetans. Shan paused over one passage, reading it twice:

Love of their land and their Buddhist faith burned like an intense fire in many of the trainees. It so moved the American trainers that several requested, and were promptly refused, permission to parachute into Tibet with them when the training was concluded; others requested transfer to the advance base in northern India so they could participate in airdrops and radio support for the missions.

Shan felt a flutter of excitement as he unfolded the map. It was an intricate rendering of the Everest region, in English. He stretched it out with stones on each corner, examining it closely then, noticing Yates’s curious gaze, handed the American his own Chinese map.

“I have heard the term political map in English,” Shan said. “What does it mean?”

“It means cities and towns and highways, manmade features, are included,” Yates explained.

“In China all maps are political,” Shan said, and gestured to the map Yates was unfolding. “The government controls all maps. No military bases are shown but also terrain in sensitive areas is obscured.”

The American uttered a syllable of surprise and began pointing out discrepancies between the two maps. On the Chinese map large expanses along the border were just fields of white, indicating huge ice fields. Most of the border showed only general topographical lines and nothing else. Shan pointed to the American map. “It’s like a different land on your map,” he explained, and settled a fingertip on Tumkot. On the Chinese map the area above the settlement, the high plain that could not be seen from below, consisted entirely of an ice field, marked inaccessible, as the villagers insisted. But the American map showed a more narrow glacier above rough, steep, but open terrain.

With a pencil Shan made a mark on the road that led to the base camp. “The site of the murders,” he noted.

“What’s your point?”

“Ama Apte has admitted she helped Megan Ross with the avalanche that stopped the bus, but she will not explain how she managed such secrecy. No one could have gone up or down the road without being stopped. For someone from Tumkot to be involved they would have had to travel hours by road, and they would have been seen and stopped. But someone who knew these trails could have gone up and over the ridge. A difficult path, judging by the contours, but not impossible for a seasoned trekker.” He saw for the first time four different lightly drawn circles spread miles apart, three of them with X’s through the center. “You haven’t visited this drop zone?” he asked the American, pointing to a circle on the plateau above Tumkot.

“I must have made a mistake when the numbers were written down. There is no way up there. Megan said she tried, and it was impossible. All cliffs and ice along the only possible route.”

Shan studied the map again, and after a moment saw a dotted line that crossed into Nepal along a high altitude pass that was marked inaccessible on the Chinese map. He realized he was looking at the route the sherpas used to invisibly cross back and forth across the border. The border guards no doubt knew about it, but the weather would be so hostile at such an altitude that there would be no manned outpost.

“And you?” Shan asked at last, gesturing to his notebook. “What have I missed?”

“It’s all still a puzzle to me,” the American admitted. “We can ask the fortuneteller about the hidden meaning of twos when we see her again.”

“Twos?”

Yates turned to a page near the front of the pad and pointed to the words, written in English. “Religious Affairs office burns,” he read, and drew a line beneath it that extended past the words. “Tenzin killed” he said, and drew another line. “Minister Wu is killed.” Another line. “Director Xie is killed, on the same day Gyalo is attacked and left for dead,” he finished with another line. With the tip of the pencil he quickly wrote numbers in the spaces between the lines. “Two days, two days, four days. All twos or a combination of two. Ama Apte would probably say the mountain breathes in for a day, then breathes out.” He shrugged. “It’s nothing. I’m possessed by a math demon. Although,” he added in a curious tone, “it’s been two days since the last violence.”

Shan stood, strangely disturbed by Yates’s words, glancing back and forth from the map to the lines and numbers drawn by the American. He stepped to the edge of the cliff, letting the chill wind slam against his face, considering the pattern of life down in the world. Then abruptly he turned and darted over to Yates. “There is a place,” he announced as he urgently packed up the items on the bench, “that lives by a pulse of twos. If we hurry we can be there by sundown.”

Yates had not stumbled upon the rhythm of the mountain, Shan explained as they pulled into the dusty truckers’ compound in Yates’s red utility vehicle, but the pulse of the Friendship Highway. Shogo was strategically situated on the truckers run between the Nepalese border and Lhasa.

“It’s the natural break point. Drivers can get food and gas, then they sleep in their trucks or buy a cot in the back of the teashop. At dawn they pull out and reach their destination before nightfall. The regular drivers turn around the next morning and repeat the trip.”

“Putting them here every two days,” Yates concluded.

“Gyalo said the men who attacked him were strangers. He knows nearly everyone in town. Everyone else seems to think they were Public Security soldiers. But if they weren’t knobs,” Shan said, “they were transients.”

“So now we’re looking for murderous truck drivers? How many theories are you allowed before you admit failure?”

“Gyalo said someone watched from the shadows as he was beaten. Wu’s killer had help. Two men in black sweatshirts. Most truck drivers would know how to operate a bulldozer, and could arrive at the base camp in a small supply truck without raising suspicion. More than a few are former soldiers.”

They watched until dark, studying every truck that entered the compound, watching for those few that had pairs of drivers, then ventured inside after Yates found a hooded windbreaker to cover his features. The American uttered a low choking sound as they opened the door of the cafe to a powerful scent of grease, cabbage, cigarettes, motor oil and burned rice, then followed Shan to a table in the back corner, where they pushed aside dirty dishes and sat with their backs to the wall.

They ordered noodle soup, which was not as bad as Shan expected, and momos, which seemed to be made of cardboard.

“This is your plan?” Yates muttered. “Sit and wait for two drivers to walk up and confess?” He poked at his stale momos. “Of course they might prefer jail to these dumplings.”

“The plan,” Shan said as he spotted a familiar face exiting the cafe, “is for you to stop speaking English and sit here.” Shan grabbed a newspaper from an empty table and tossed it in front of Yates. “Pretend you read Chinese. I’ll be back.”

Shan stayed in the shadows as he exited the building, following the path that led to the latrine at the rear of the complex then stealing around the parked trucks until he reached the mechanics’ workshop at the far side of the complex. The man under the hood of a small truck was too engrossed in his work to notice Shan enter and lean against the workbench behind him.

“Last I saw him,” Shan declared, “your father was sleeping. I think he will make it.” Jomo’s head jerked up so fast it hit the lifted hood of the truck.

“They don’t allow visitors in the garage,” he groused, pulling an oily cloth from his pocket to wipe his hands.

“When I said it wasn’t Public Security who attacked your father you didn’t seem surprised.”

“I can’t afford trouble. I did a year in prison when I was younger. It still could have been the knobs. They hire people sometimes.”

“As informers, yes. But not for that kind of work. For sake of argument, let’s say it was strangers, like your father said. This is the local market for strangers, you might say, full of Tibet’s new nomads. Men looking for a little extra money, who wouldn’t be recognized.”

“Last spring when an avalanche covered one of the roads they put a sign up here and quickly hired twenty drivers for a couple of days.”

Shan nodded. “What was your year away for?”

“A disagreement over the sky.”

“The sky?”

“All my life I walked the town at night and watched the stars, would sit right in the town square and count meteors. Then someone decided to install street lights, those ugly orange vapor lamps. No more stars. I used to spend summers with shepherds when I was a boy. I have always been good at throwing stones.”

“Civic pride,” Shan suggested, “can take many forms.”

Jomo forced a slow, uneasy grin in reply.

“What if I had a special job, no questions asked? What if I wanted two men in black sweatshirts who weren’t afraid of bending the rules?”

The Tibetan turned to the bench, began sorting through a pile of wrenches. “You are the only one in town interested in saving that Chinese colonel.”

“That Chinese colonel didn’t kill Tenzin or Director Xie.”

Jomo shrugged. “Tenzin was from Nepal. And no one cries over Religious Affairs bureaucrats.”

“When the real killer finds out your father is still alive those two men will probably be sent again. If they can’t find him they will start with you.”

The Tibetan lifted a wrench and looked at Shan, as if considering whether to use it on him or the engine. “I have work to do,”