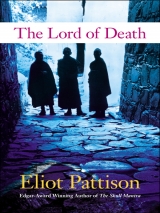

Текст книги "The Lord of Death"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

Chapter Eight

After five falls you die. The warning about fatigue in climbing ropes had been the first of the many warnings he had received during his first visit to the base camp. Kypo had offered no greeting before tossing the length of rope Shan now held. He had simply appeared as Shan sipped his morning tea by his front door and thrown the rope at him with a resentful expression. One end of the rope had been cut; the other, stretched and frayed, had been snapped by a heavy load. The thick kernmantle ropes took amazing abuse on the high summits, but they were retired to serve as base camp laundry lines after taking the stress of five falls.

“I was at the first advance camp yesterday,” Kypo explained. “I asked a porter why this piece of junk was there. He said he thought he should keep it because it was Tenzin’s rope, the one he was using when he died.”

“But he would never-”

“Right,” Kypo interrupted. They both knew a seasoned sherpa would have checked his rope before climbing. “Tenzin was just setting a practice wall, for customers to use while acclimatizing for the final climb.”

Shan looked at the crushed, frayed end of the rope. He recalled Tenzin yelling at a porter for stepping on a rope in camp. A careless step could press mineral particles into the rope, which would gradually cut the fibers.

“We don’t know where this has been for certain. I wasn’t there when it was cut off him.”

“No,” Shan agreed. “I thought he was free climbing and slipped.” Tenzin had been renowned for his unassisted climbs up sheer rock faces.

“It looked like he was just taking some equipment to the bottom of the wall, a quick up and down.” Kypo was silent a moment, clearly disturbed by the thought that his friend Tenzin, who had climbed the summit with him, had died from such an obvious mistake. “It was written that the mountain would call him,” he murmured. It sounded like he had been speaking with his mother.

“The rope came from the Americans’ supplies,” Shan observed. “It’s their advance camp.”

“Tsipon wanted Tenzin and me to take the Americans on the final leg to the top. I told Tsipon I would think about it.”

Shan considered the edge of emotion in the Tibetan’s voice. “You don’t trust Yates?”

“He plays with the truth. I was in Tsipon’s office when Yates first came in to speak about moving his spring climbs from Nepal to here. Tsipon said Yates should come with him to apply for the permits the next day, since foreigners always get sent to the front of the line. Yates declined, saying he had to go to Shigatse on business. But the next day I saw him in the opposite direction of Shigatse, standing in a field of barley.”

Shan cocked his head, not sure he had heard correctly. “Standing in a field doing what?”

“All by himself, tramping down some poor farmer’s crop, tearing apart an old cairn in the center, the bastard.”

“He lied?”

“He lied, then paid the farmer twenty dollars when the man discovered what he’d done. Told him to keep quiet about it.”

“But you spoke with the farmer,” Shan surmised.

“When I passed on my return. The farmer said Yates had gotten out of his car and kept looking at the sky, as if expecting something to come down and meet him.”

“He must have had a satellite phone and was trying to get reception.”

“No. Everyone here knows what those big phones look like, because every other foreigner has one.”

“And the farmer spoke with you, after taking money to keep quiet.”

“In Tibet, comrade, keeping something secret means keeping it quiet from the Chinese.”

A loud horn from the road broke the silence that followed. They looked up to see Jomo with his beloved old blue truck, his battle junk. Kypo faded into the shadows.

By the time Shan reached the truck the wiry mechanic was standing at the curb, gazing at Shan with an apologetic expression.

“Tsipon says Director Xie needs you. I am supposed to take you to him and help you.”

Shan pushed back the dark thing within him that rose at the mention of the wheelsmasher’s name. “Help me?” As Shan spoke, several Tibetans appeared from an alley on the opposite side of the street and began climbing into the cargo bay of the truck.

“The engine is unpredictable. He doesn’t want you stranded,” Jomo said plaintively, then gestured toward the half dozen Tibetans settling into the bay. “They heard we were going up the mountain.”

“Are we? Going up the mountain?”

“Xie is up there,” Jomo replied. He climbed in and with a loud cough and a cloud of smoke the old truck began to move.

It was not unusual for trucks to give rides to Tibetans, who seldom had their own vehicles, but when Jomo halted for four anxious older women near the truck stop where the road to Chomolungma left the highway, Shan turned to the mechanic. “Don’t you think I should know at least as much as they do?”

“What they know is that Religious Affairs is in the mountains,” Jomo replied in a tight voice, leaning forward as if needing all his concentration to negotiate the winding curves.

“Then tell me this,” Shan tried. “What happened between Ama Apte and your father? What prevents him from going into the mountains?”

“Before my time,” Jomo shot back.

“They avoid each other.”

“They hate each other. If my father sees me speaking with Kypo, he berates me and throws things at me like when I was a little boy. He calls her the false prophet, says everything she does is a lie, says all of Tumkot hangs on the thread of a lie.”

“Surely, Jomo, you have wondered what that lie is.”

“Before my time,” Jomo replied again, and would say no more.

Shan studied the Tibetan, doing some rough calculations.

Jomo’s time would have begun, he decided, sometime in the late 1960s.

Director Xie had his fox-fur hat pulled low against the chill wind as he waited for them at a crossroads that connected to one of the valleys defined by the long, high ridges that jutted out from the Himalayas.

“Excellent!” Xie exclaimed to Shan. “You brought laborers! Such foresight!”

Shan nodded uncertainly, then with rising foreboding complied with Xie’s gesture and climbed into the back of his government sedan.

He did not recognize their destination until they were within half a mile of it. The only other time he had seen Sarma gompa, the small monastery, had been weeks earlier, from the ridge above when he had been hiking on a pilgrim’s path. The compound of centuries-old stone and timber buildings nestled against a high, flat rock face. Sheltered to the west by tall junipers and rhododendron, it had seemed a serene oasis in the dry, windblown valley.

“We are closing in, comrade,” Xie declared. “This is the landscape of our victory,” he added with the tone of a field commander, and was rewarded with a vigorous nod from the young deputy who sat in the front seat.

Shan glanced from the bureaucrat to the gompa. What landscape? What victory? Then Xie answered his unspoken questions with an announcement that sent a shudder down his back.

“That Cao has not even found this place,” Xie said with a conspiratorial gleam. He was competing with the Public Security Bureau.

“Major Cao,” Shan ventured, “seems overly rigid.”

Xie laughed. He was enjoying his field trip immensely. “A dinosaur. Pretending he can deal with an assassination without severing the root it grew out of.”

Shan’s confusion over Xie’s intention disappeared as they pulled to a stop by the gompa, renowned in the region for its ancient murals. The faces of the Tibetans who climbed out of the truck told him everything. Some scrubbed tears from their faces, others clenched prayer beads or gaus with white knuckles. Jomo tried to scurry away as he climbed out of the cab, but Shan stepped in front of him. The mechanic slowly turned his guilt-stricken face up to Shan. He often worked at the town garage. He would have known when the dump truck, now parked near the trees, had been dispatched, would have known it was pulling a trailer carrying a compact bulldozer. Sarma was the gompa of the fugitive monks.

One of the Tibetan women uttered an anguished cry when the bulldozer roared to life, another clutched her breast as if she had been stabbed. Men in white shirts appeared by the buildings, Xie’s deputies from Lhasa. Several of the Tibetans Jomo had brought from town settled on a knoll by the front gate, folding their legs under them, pulling out their prayer beads.

The sound of the machine plowing through the gate and into the brittle old wood of the temple at the front of the gompa nearly brought Shan to his knees. Shards of painted plaster flew into the air. Splinters of wood popped and cracked over the metallic clinking of the treads as the bulldozer cut a swath from one wall to the next. The wide eye of a god that dropped onto the cage of the operator seemed to take on new expressions-shocked, then terrified-before slipping away to be crushed. The end of an old altar became trapped under one end of the blade and was dragged along until shattering into a dozen pieces. Suddenly the machine emerged from the building, massive holes now in opposite sides of the structure. The bulldozer pivoted on one tread and slammed into one of the standing corners. The building staggered, swayed violently, then collapsed. Two of Xie’s deputies clapped. Jomo fell against the front of the truck, his head buried in his arms.

Shan fought the temptation to race to the machine and seize the key from the ignition, to stand in front of the blade. But nothing he did would change the fate of the serene little gompa, which had withstood storm and strife for so many centuries, sheltered so many prayers, only to be annihilated at the whim of a bureaucrat. Eventually, through his numbness, he realized that half the Tibetans had disappeared. He recalled that the pilgrim path rose up the ridge from the shadows of the trees, past the painted rock face in the rear courtyard. Slowly, inconspicuously, he paced along the front of the compound, seeing movement in the shadows of the trail. There were storerooms in the back, the last place the bulldozer would reach. Some of the Tibetans had come to save what treasures they could.

He returned to Xie’s side and pointed to a building with a fierce demon painted on its wall at the corner farthest from the storerooms, out of sight of the trail. “The gonkhang,” Shan explained, choking his guilt. “The protector chapel should be next.”

Shan watched in silence as Xie gleefully directed the bulldozer into the sturdy little building, saw the demon crumble, the lathe and plaster of the wall burst apart, an odd wooden frame with wooden screw mounts shatter as the blade hit it. The rumble of the machine drowned out the sob that escaped Shan’s throat. He felt his knees giving way, and braced himself against Xie’s sedan. It had not been a protector chapel, it had been a barkhang, a traditional printing press. There had been one old printing press left in the region, Kypo had told him, one place where the reverently carved rosewood sutras could still be used. Shan shut his eyes as dozens of ancient printing plates, each a unique treasure, fell from shelves and were crushed under the tread of the bulldozer.

Xie’s fox-covered head bobbed up and down enthusiastically as he watched the destruction, and he called out to one of his deputies before gesturing for Shan to follow him past his limousine. Several chests had been removed from inside, and were lined up by the dump truck.

“You are the expert,” Xie said as he opened the first of the chests.

“I don’t understand.”

“The cults. The factions. The separate cadres within the church. We will need to inventory everything here for our warehouses. Bur first I need you to tell me what they say about the links between the monks of this compound and others nearby.”

So Xie did know something about the Tibetans he regulated. There were several sects of Tibetan Buddhism and affiliated gom-pas supported each other. The director opened the second trunk, which was loaded with ritual implements. “We have people who know the names of all these artifacts,” he boasted.

Shan slowly walked along the chest, lifting some of the implements as he identified them. “ Purba,” he said, as he raised a ritual dagger, then “a dorje, a drilbu, a kangling, a damaru,” indicating a scepter, a bell, a bone trumpet, a skull drum. He looked up to meet Xie’s impatient gaze. “This gompa was one of a kind,” he lied. “It is not affiliated with others here, only some in Nepal and India.” He looked back over the chests, all of which Xie had now opened. Most were only half full. The slow moving dump truck and its heavy load must have been dispatched the day before. The Tibetans in the surrounding hills would have understood. They had already salvaged many of the treasures.

“Still,” Xie observed, “a lost sheep looks for any flock it can find.”

“But the others,” Shan ventured, his voice growing strangely hoarse, “have signed loyalty oaths.” Only one gompa had been targeted for a raid.

“True.”

“Then your mission is successful. You have dealt in a permanent way with those who would not sign.” He gestured to the chests. “You have added artifacts worth several thousand to the government coffers.”

“Still,” Xie said, “this region seems so-” he searched for a word-“fertile.”

Another shudder moved down Shan’s spine.

A deputy jogged up with a small radio unit and handed it to Xie, who stepped out of earshot to speak into it. He handed it back to the assistant then offered a pointed grin to Shan. “Foreigners. Always causing complications.”

“You mean that American Yates?”

“Him? No. He is away, they say, up high scouting advance climbing camps.” The announcement caused Shan to glance up toward the summit that loomed large on the horizon. He had stayed away from the base camp because of the American. “We can’t search the base camp the way we would like. The foreigners have everything out of context; they don’t understand our family matters.”

“You mean they might misinterpret the government putting a bullet in a monk.”

Suspicion rose in Xie’s eyes. “Comrade, my office is responsible for the whole family of Buddhists in Tibet. It does not serve our policies for monks to be shot. The government strives to make them patriots, not martyrs.”

“What are you saying?”

“That fleeing monk wasn’t killed by Public Security. They found his body on the trail.”

The purba in Shan’s hand slid out of his grip, dropping back into the chest. He stared at Xie in disbelief. “Cao knows this?”

“Of course. It is why I was brought in.”

Shan considered Xie’s words. “You mean you are giving cover to Cao.” Xie’s presence assured that everyone assumed the monk was killed for defying the Bureau of Religious Affairs. Otherwise Cao would have another murder to account for, complicating his case against Tan.

“We are all soldiers in the service of the motherland,” Xie replied, then turned away as another deputy handed him a radio.

Shan retreated, back to Jomo. He quickly spoke to the Tibetan, then eased into the cab of the blue truck.

Entering the base camp below the North Col of Everest was like entering a war zone. Stacks of materiel for doing battle with the mountain lay under tarps fastened with rocks and ropes, each labeled with a trekking company name. Clusters of tents were scattered across the rocky landscape-some elaborate, brightly colored nylon structures, others, from less well-endowed expeditions, affairs of tattered canvas. Porters-the ammunition carriers of the annual spring war-scurried about under heavy loads, weaving in and out of small groups of climbers. The foreigners could instantly be identified as new recruits or veterans. The haggard veterans, back from the oxygen-starved, frigid upper slopes, looked as if they had come from weeks of artillery barrage. Sometimes stretchers would move among them, urgently being carried to waiting trucks. Kypo had made sure Shan knew the statistics before he ventured to his first advance camp weeks earlier. Nearly two percent of all those who ascended Everest died. One in twenty of those over sixty died. It was too dangerous to bring down those who died on the upper slopes, so they were left as grisly, contorted monuments slowly being mummified by the dry, cold wind. Others, the walking wounded, came back with injuries that would mark them for life. Two weeks earlier Shan had seen a man writhing in agony on a stretcher, half his face dead from frostbite.

Completing the battlefield effect were the many foreign flags that fluttered near the groups of tents. On a low, gravelly knoll between two rutted tracks a familiar figure in a uniform sat in a folding chair, as if expecting to direct traffic. Except Constable Jin was fast asleep.

Shan did not bother to search for the striped red, white, and blue flag before hoisting a crate to his shoulder for cover. He aimed for the most populous of the encampments.

With a businesslike air he entered the largest tent in the base camp, an expansive pyramidal structure used as a supply depot. Confirming that he was alone, he set down the crate and studied the chamber. To his right was a tall wooden tool chest with folding chairs around it, a makeshift table. Small nails had been driven into the wooden tent posts near the table, from which hung lanyards with compasses, whistles on chains, several open padlocks, and a small net bag filled with hard candy. In the far left corner, taking up at least a fourth of the space inside, was a huge square stack of supplies in cardboard cartons. Opposite was a little alcove, separated from the rest of the tent by felt blankets hung from climbing ropes. Shan glanced behind him, then slipped through the curtain of blankets.

A piece of heavy canvas covered the gravel and sand underfoot. A folding chair sat between a metal cot and a folding camp table, which was covered with papers. He sifted through them quickly. Lists of climbers, schedules for future expeditions, weather reports for the summit and the Bay of Bengal, correspondence between Yates and the Ministry of Tourism on the payment of climbing fees, inventories of equipment.

He moved to the cot, searched the bedding, then pulled out a heavy foot locker that was under the bed. Secured with a large padlock, it bore the legend Nath. Yatesin large black letters on its top. Behind it were three pairs of boots, a plastic bin of pitons and a nylon climbing harness. On an upended wooden crate at the other end of the bed lay several personal items. A plastic bag of toiletries. A bottle of Diamox tablets, for altitude sickness. A small basket holding dozens of small denomination coins from several countries, with a deck of well-worn playing cards. He sifted through a pile of clothing thrown on the canvas rug, scanned the chamber once more, then found himself gazing again at the padlocked trunk. The padlocks by the main entry had been almost identical to the one before him. The wooden tool box there might hold one of the heavy bolt cutters sometimes used for slicing through the thickest climbing ropes. He moved back to the entry then, as voices were raised outside, slid open the front tent flap to survey the camp. Four weary figures in parkas were descending the trail from above, three Tibetans and Nathan Yates. Shan watched as the American was hailed by a bearded man near a tent flying a German flag, who gestured for Yates to join him. Shan lingered long enough to confirm that Yates was moving toward the German, then darted to the languid form of Constable Jin, still sprawled in the lounge chair.

Jin jerked upright as Shan touched his arm. “You know the American Yates?” Shan asked.

“Buys me a beer whenever he’s in town.” Jin studied Shan uncertainly. “So you’re back to work then?”

“What do you mean?”

“There’s nothing more you can do about the murders. You forced his hand. Cao called my office to arrange for Colonel Tan to be transported to a jail outside the county. He says he wants him safe from tampering while he completes his file.”

Shan clenched his jaw. With Tan out of his reach he had little hope of finding the truth or helping Ko. “I am going inside,” he said, pointing to the Americans’ depot tent. “If Yates enters and I do not come out in five minutes, you must come inside, with your gun ready.”

Jin looked up with a hopeful expression. “Is he going to attack you?”

“Five minutes,” Shan repeated, then slipped back towards the tent. With relief, he discovered bolt cutters in the tool chest and was about to dart back to the Yates’ sleeping quarters with them when he noticed two unfamiliar objects at the bottom of the chest, a long flexible black tube and a black oval box the size of his hand. The box had an eyepiece at one end. He held it to his eye, saw nothing, then noticed a battery compartment. He found a small sliding switch, pushed it, and an intense light spilled out the end opposite the eyepiece. The hole emitting the light was threaded. He studied the tube and found it was filled with a clear plastic material, with one end threaded. He screwed the tube into the box, looking into the eyepiece, then switched on the light again and gazed through the eyepiece. A pebble at the end of the tube leapt into view, brilliantly lit by the optic cable. With a thrill of discovery he experimented, bending the tube, seeing pebbles, the back of his boot, the back of his head, the inside of an empty beer bottle on the table.

He carried both the optical instrument and the bolt cutters with him into the sleeping quarters, pausing for a moment to study the huge block of cartons again. He tapped several cartons as he returned to Yates’s quarters. Several on the top tier seemed to be empty.

Moments later he had cut off the padlock on the American’s trunk and tossed it behind the bed before bending over to examine its contents. Several pairs of thermal socks and underwear, in original packages. Two large boxes of matches. A small, sophisticated stove with several canisters of fuel. An envelope containing several black-and-white photos curling with age, of an athletic looking man in a uniform, posing by a large airplane with four propeller engines, then on a horse, then with a dozen other soldiers in a group in front of a barracks.

He shut the trunk, locked it with the spare padlock, and studied the area again, certain he had missed something, looking under the upended crate, lifting the cot, studying the aluminum bed frame. The hollow metal legs had rubber caps at the bottom. He popped off two caps to no avail but as the third twisted away a rolled paper slipped out. It held nothing but six rows of numbers. They could have been international dialing numerals. They could have been bank account numbers. Shan extracted a scrap of paper from his pocket and hastily transcribed the digits. He returned the rolled paper to the bed frame and was about to leave when he noticed something in the shadows behind one of the heavy tent poles, suspended from a small nail. It was a silver gau, a Tibetan prayer amulet. He lifted it with reverence, and not a little awe, for he could immediately see that it was exquisitely worked, from the intricate brass hinge that allowed it to be opened for insertion of blessings to the rows of sacred images engraved on the top and bottom. He lingered over it, moved as always by the centuries old artifacts of the Buddhists.

“When I first came to China years ago,” a simmering voice said to his back, “I had a ballpoint pen that I left behind in a hotel room in Shanghai. Two days later in Beijing, my escort gave it back to me. Later I got him drunk and asked him about it. He explained that half the people who work for the government actually do the work of the government, the other half watch the first half and every foreigner who enters the country.”

Shan, the gau still in his palm, slowly sank onto the bed.

Yates pulled off the wool cap he wore. “So what kind of spy are you? Animal, mineral, or vegetable?”

“I don’t understand.”

“Do you spy for the Party, some economic enterprise, or just the police?”

Shan extended the gau. “Do you have any idea how rare this is, how old it is? Did you steal this too?”

“I’m no thief.”

“Show me your knuckles.”

Yates, confused, began to lift his hand, then glanced at it and hid it behind his back. But not before Shan had glimpsed its scratches and abrasions.

“You son of a bitch, Shan!” the American spat. “It was you up there last night.”

Shan dropped the gau into Yates’s hand. “Some of the older Tibetans say that with the right prayers inside such an amulet, the one who holds it is incapable of lying.”

“I asked people about you,” Yates snapped. “You’re one of those prisoners, one of the gulag outcasts with nothing to lose. Tsipon should have told me.”

Shan picked up the strange optical instrument, aiming it like a gun at the American. “I’ve got you. Theft of cultural antiquities is a serious charge. The constable will be overjoyed when I present you to him. Having a constable indebted to you is what every outcast dreams of.”

Yates bent the black tube downward, away from his chest.

“I’ve never seen one of these,” Shan said.

“It’s called a borescope,” the American explained in a sullen voice. Shan did not resist as Yates pulled the instrument from his fingers. “There’s a cult of climbers obsessed with finding evidence of expeditions from decades ago. A lot of people died then, disappeared without a trace. Some think they stuffed messages into cracks in the rocks, to avoid having them blown away. With this they can see inside the cracks.” Yates unscrewed the tube from the body of the instrument, putting the pieces on his bed. “The constable will be more inclined to believe me when I say I caught you stealing my things. What’s the word of an unreformed criminal against that of a valued American entrepreneur? Foreign currency buys instant respectability in this country.”

“Did you kill them, Yates?”

The American seemed to grow very weary. He settled onto the cot. “Kill them? You mean Minister Wu.”

“I mean Minister Wu and Megan Ross.”

Yates gazed at Shan without expression. “Minister Wu was killed by some deranged army officer. Megan Ross is away, back in a few days.”

Most people were scared of ghosts because they were dead but Shan was becoming scared of this one because she would not stay dead. “Everyone keeps saying Ross is alive, but no one can say where she is. Did you help her get away, did you take her to one of her secret mountains?”

“People are deported for such things. She says she won’t expose anyone else to that risk. Being banned from the Chinese Himalayas would be a deep personal tragedy for a serious climber.”

“Almost as tragic as being murdered in the Himalayas. Was she a competitor? Is that why she had to die? Didn’t want to share your piece of the Himalayan enterprise?”

“I told you. She is away on a climb. And she’s not a competitor, she’s a partner. She has a contract to help me with my expeditions this year, arranging the routes, handling the bookkeeping for the money going into China. She’s famous in climbing circles. She knows China better than I do.”

Shan gave an exaggerated shrug and gestured to the amulet, still in Yates’s hand. “I guess we have proved the gau doesn’t work on foreigners. Or maybe it’s lost its power after all these centuries.”

“Your boss is going to be very unhappy when he finds out I won’t be doing business with him.”

“But we found that missing body. Porters from the village are already arriving.”

“I was thinking more about whether I want to work with you.”

“The better question,” Shan rejoined, “is whether they will want to work with someone who steals from them, then insults them.”

“What are you talking about?”

“Taking the deities is bad enough. But giving them back damaged, that’s demeaning.”

The ember that had been smoldering in the American’s eyes was about to ignite. He pointed to the entry. “Get out!”

“I found the instrument you use to spy inside the statutes. Now all I need is a high-power drill. Where’s your workshop?” Shan paused, suddenly remembering the structure of cartons in the outer tent. He stood and backed away, ready to dodge the fist that Yates seemed about to throw at him. “I understand how the government handles these matters, Mr. Yates. Write a confession about the thefts and the murders. I’ll hold it for a day, long enough for you to drive across to Nepal.”

The American’s fury seemed to paralyze him as Shan slipped out between the blankets. He darted to the carton structure and began shoving the outer cartons away, quickly revealing a narrow passageway between the stacked boxes.

“No!” came a frightened gasp from behind him. Yates leaped at Shan, arms outstretched to grab him just as, from the corner of his eye, Shan saw movement at the entry.

“Shan!” Constable Jin stepped inside the tent. “Where are you, you bastard?”

Shan pushed forward, reaching a small, dark chamber in the center of the block of boxes as Yates seized him by shoulder, desperately trying to pull him away.

“Shan!” Jin called again. The constable began walking toward the boxes.

Three Tibetan men in tattered, soiled robes looked up at Shan with terrified expressions. Yates was hiding the fugitive monks.