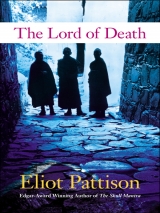

Текст книги "The Lord of Death"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

Impossibly, Constable Jin was there, less than half a mile away, waving his arms again, not at them but toward the mother mountain, as if he had something to say to her. Then Shan heard the low, metallic ululation that brought terror to so many Tibetans.

“Down!” he shouted reflexively, then he realized the helicopter, rising along the north col of Everest, was too far away to see them. He turned to borrow the American’s binoculars but Yates already had them trained on Jin.

“He’s lost his pack,” Yates reported. “He doesn’t have his radio.”

“We must go!” Shan urged the monks, “quicker than ever!” When the helicopter crew gave up the wider search they would likely fly to the head of the pass and work a pattern down the glacier. The bright parkas of the monks would be like beacons on the white surface.

They ran, slipping, sliding, falling and scrambling up again. Jin came on relentlessly, jumping recklessly over jagged shards of ice, skidding down low slopes, increasing his speed whenever he saw them pause. Shan stopped looking back, stopped listening for the helicopter, willing himself and the others on, trying with increasing despondency to understand if the next dip in the ice field marked the end of the pass or just another undulation in the glacier.

Suddenly it was over. The oldest of the monks stumbled, then slipped on a patch of ice, wrenching his ankle, crying out in pain. Shan and Yates bent over him, examining the sprain, then Yates handed Shan his pack so he could carry the monk on his back.

“In the name of the People’s Republic, I arrest you,” came a ragged voice behind them. Jin stood ten feet away, his pistol leveled at them.

Yates lowered the monk to a boulder in a standing patch of gravel.

The shreds of Shan’s last hope blew away in the chill wind. Here was the end. With the monks in custody, Cao would create the confessions he needed to execute Tan. Shan had a shuddering vision of himself standing with his hands on the wire fence of the yeti factory, shouting his son’s name as Ko gazed blankly out his window.

“A drink,” Jin gasped to Yates. “Give me your water.” He was shivering from the cold, his heavy uniform coat torn in several places.

Instead the American extracted a pencil stub and a scrap of paper. He braced a leg against another boulder and wrote, then extended the paper to Jin. “What you need is this,” he declared. “Give me your gun and you can have it.”

“You don’t think I’ll shoot them?” Jin demanded. He was half delirious with fatigue.

“They do have those charms,” Yates observed in a conversational tone. Shan stared at him, beginning to suspect that the American also suffered the effects of the high altitude.

Jin swung the gun toward the monks, wildly firing a shot. A shard exploded off the rock on which the injured monk sat.

“See?” the American said with a shrug. He held the paper up. “I’m offering you a different kind of charm, and I’ll throw in my coat. For the gun and your coat.”

“My coat?” Jin rubbed his temple, staring at the American in confusion.

“I know them. With my note they will help you. But wearing the uniform of the Chinese government will mean a cold welcome. And by the time you get below these monks better be your best friends.”

Jin turned to follow the American’s gaze past his shoulder. His jaw dropped. He glanced from the American back to the valley below, to a compound of colorful tents sprouting lines of prayer flags half a mile below them. His face contorted with emotion, then lit with excitement and he began to peel off his coat. They were above the Nepali base camp. They had crossed the Chinese border.

The American’s instructions to the monks were quickly preempted by loud cries from the youngest monk, who hurriedly explained where they were, that he knew many of the sherpas, how there was a monastery only a day’s walk from where they stood. A moment later Jin had exchanged coats with Yates and handed him the gun, which the American tossed away.

Jin paused by Shan after he had helped the injured monk to his feet. “On the trail that day, I saw the Manchurians twice. They came back up the trail after I passed them, demanded that I ride on and find the mule with the body and bring it back, said if I didn’t forget what I saw, they would find me and kill me.” He glanced at the monks and lowered his voice. “They were the ones who killed the monk that day. He appeared out of the rocks and tried to stop them from taking the body on the mule. I was already moving down the trail by then, there was nothing I could do.” The constable offered an apologetic shrug, then marched away to his new life.

“We should go with them,” Yates said in a worried voice as they watched the others descend toward the narrow concealed goat trail that would take them down to the Nepali base camp. Jin was bracing the injured monk on his shoulder. “If we cross now we’ll be on the ice in the dark.” He studied Shan a moment. “Go down, Shan,” Yates urged. “It will mean freedom for you, a chance to start over.”

Shan silently tightened the laces of his boots and began jogging back up the treacherous trail.

An hour after sunrise the next morning they reached Jomo, waiting in another of Tsipon’s trucks. A grim determination had settled onto their faces. They had passed an uneasy night on pallets in the hermit’s cave, having reached it after sundown. Neither man gave voice to their increasing certainty that Tan would have been already tried, that Ama Apte and Kypo would have been seized by the knobs as accomplices and transported to the gulag before they could reach the town.

Yates watched the high ridge as they pulled out onto the road. They had been bone weary by the time they had reached the cave, barely able to stand, but Dakpo had fixed them roasted barley and tea, waking them after they had collapsed onto pallets to make them eat. Then he had presented Yates with a small drawstring pouch.

“When I heard about the Yamas being stolen and returned after being opened up,” the hermit said in a hesitant tone, “I knew it had something to do with Samuel. I had been apprenticed to an artisan at the gompa when I was a boy and knew about such statues.” The old Tibetan seemed strangely nervous, and poured himself more tea before continuing. “Samuel and I spent many hours sitting on ledges above the highway counting army trucks. He spoke about the problem of getting letters home. That’s when we came upon the idea. We had sent one of the statues and had enough letters for another when. . when the world ended.

“I kept them for a year, then sealed them in an old Yama statue and kept it with me all these years. Then after the murders I took it to the Yama shrine, in case the soldiers searching the mountains found me here. Yesterday I went back for it, and opened up the bottom.”

“I am sorry, Dakpo,” Yates said, “for what I did to the Yamas.”

The hermit smiled. “I have been saying prayers with them. They will heal.”

Yates, choked with emotion, upended the pouch. Letters from forty years before tumbled out, thirty or more rolled and folded pages.

Shan watched in silence as the American, wide-eyed, began unrolling letters and reading them. But soon, unable to fight his fatigue, he leaned back on a pallet and accepted the hermit’s offer of a thick felt blanket. In his fitful sleep he awakened more than once to hear snippets of conversation between the two men sitting at the brazier. The reticent hermit had been full of words that night, and in the languid warmth of the pallet Shan listened from the shadows to tales of an energetic American teaching Tibetans to dance and sing, of Samuel Yates leading secret missions to recover artifacts from several gompas on the eve of their destruction by the Youth Brigade, of a week during a lull in the fighting when Samuel, Ama Apte, and several others tried to track yetis, of the intense affection between Samuel and Ama Apte that had somehow sustained their little band when they were living on half rations.

As the embers were dying, their faces lit only by a dim butter lamp, the hermit had leaned toward Yates, his voice now that of a wise old uncle. “We sat up all night once guarding a pass as a long line of monks moved past, fleeing to the south with artifacts from their temples, fleeing to freedom. I will never forget it. The moon was full, the ground covered with snow, monks cradling bronze deities in their arms like babies, yaks carrying bigger statues, a long single file of red robes and yaks that stretched across the snow. As the last one disappeared the mother mountain began to glow from the distant sunrise, even though the stars were still overhead. Samuel spoke some words toward her, like a vow to the mountain. He said when it was over, when things were right again in the world, he would bring back his son, because he wanted his son’s soul to be filled with the power of this place.”

Chapter Seventeen

A somber air had settled over Shogo. The residents walked down the newly swept streets with solemn, nervous expressions, staring straight ahead. Three shiny black limousines were parked by the municipal building, a sober reminder of the dignitaries who had come for the trial.

Shan slipped into the hall in the center of the building among the workers who moved tables and chairs inside. A table draped in black with three large wooden chairs behind it sat on a raised platform at one end of the room, with another chair for witnesses at one side, an easel bearing a map of the region at the other. A large portable portrait of Mao on heavy canvas had been unrolled and hung behind the judges’ table. As several workers fussed with weights at the bottom to stretch it straight, others brushed it clean. Less than three dozen chairs were arranged in two sections in front of the table. The pageant, as Shan expected, was to be a private affair.

A door opened at the side, admitting several well-dressed officials, led by a strutting Major Cao, who gestured and pointed, playing guide to the visitors. He stopped in midsentence as he saw Shan standing there in his tattered, soiled clothes, his face bearing the grime of hard travel. Shan did not move, did not change expression, though he could feel the heat of Cao’s fury from across the room.

The major turned to a lieutenant and was no doubt about to order Shan ejected when a small dapper figure in a plain black suit broke away from the group of dignitaries. Madame Zheng said nothing as she approached, but followed Shan when he turned and stepped out into the corridor.

The three figures quietly entered the clinic, not waking the receptionist, asleep again at the door. Shan went straight to the bed at the rear of the patient ward, where the driver of the bus still lingered, his layers of gauze now replaced with adhesive plasters, playing his electronic games. Jomo found a broom and swept the floor near the bed of the only other patient, a sleeping middle-aged woman wearing an oxygen mask. Madame Zheng, as Shan had previously cued her, picked up a tray of bandages and medicines by the entry and carried it to a table by the rear wall, then lifted the medical chart on the soldier’s bed.

The patient’s expression grew uneasy as Shan approached. He stuffed his electronic game under his blanket and pressed back in his pillow as if expecting to be struck.

“About time to be released,” Shan observed.

“Tomorrow, or the next day,” the corporal eagerly replied. “My barracks knows I’m here. I called them a couple of days ago.”

“We were thinking some exercise would do you good. A little ride, a little walk, a little talk.”

“Talk?”

“About the dead bodies you saw that day.”

“That minister?”

“The other.”

“You mean the blond one,” the soldier said.

Zheng leaned forward, her head cocked toward the man.

“The Westerner,” Shan nodded.

“The one who disappeared. The ghost.”

“We are,” Shan declared as he handed him the clothes that hung on a peg by his bed, “great believers in ghosts.”

A quarter hour later Shan and Madame Zheng stood in the shadows of the garage bay at the rear of Tsipon’s warehouse as Jomo eased the long green sedan into the bay and shut the door. It took less then two minutes before an angry figure in a business suit and tie burst through the side door.

“Idiot!” Tsipon raged. “I need that car! The trial is starting!”

Jomo dangled the keys in his hand, then retreated to the opposite side of the car, the keys dangling in his hand. “You sent men to kill my father.”

“Don’t be ridiculous. Get in the car. You can drive me.”

“They were two truck drivers, outsiders. You paid them to do things, illegal things.” Jomo stopped at the trunk of the sedan.

Tsipon looked at his watch. “You’re talking nonsense, Jomo. I am your employer. I am your father’s landlord.”

As Jomo opened the trunk Tsipon’s expression darkened. He darted toward his mechanic with a snarl, then halted abruptly when Jomo threw a bulky object at him, hitting him in the chest. A large yellow bucket.

Shan shifted forward in the shadows. Jomo was only supposed to have told Tsipon he knew about the yellow bucket.

“I wondered about the bounties offered for the monks, how they would be paid. The drivers I asked said the manager of the truck stop was to be shown the gaus. The manager and I had a chat late last night, locked in the workshop. I persuaded him to tell me that when he saw the gaus he was supposed to leave a note in a yellow bucket by the road. I didn’t have to ask who owned the bucket. My father, then the monks. Trying to kill holy men must be habit forming.”

“Your father has been trying to get killed for years,” Tsipon said in a brittle voice. “He’s unstable. The only reason he stays out of the yeti factory is because I protect him.”

Shan took another step forward as Jomo’s eyes began to smolder. “I remember when I was young. You retrieved us out of the gutter. You would bring things. Food. Blankets. And he always had money to run the tavern, even when he couldn’t pay you rent. I thought it was kindness.”

Tsipon seemed to collect himself. He straightened his tie. “I was in a position to help him. You would begrudge a favor? As the senior Tibetan Party member in the county I had an obligation to help with his rehabilitation.”

“The help never came from a cooperative or a collective or the county welfare office. It came from you. And every time you made a delivery there was a bottle of alcohol with it.”

“He had great pain. A lot of past that needed to be erased.”

Jomo gazed into the trunk, reached in to extract a tire iron before shutting it.

“There’s work to do, Jomo,” Tsipon reminded him. “Drive me to the trial and come back for an inventory.”

“People never talk about the members of the resistance. It’s as if they were old demons whose names are taboo. I remember paintings of those demons. My father kept some in a chest. All around the big demons were little demons. You were one of the little demons.”

“Ridiculous. The rebels were criminals. Worse, traitors.”

“You were from a shepherd family in the high ranges, where the pastures have been closed by the border patrols. But what you don’t know is that some of those shepherds moved their herds to valleys west of here, past old Tingri town. I drove over there yesterday, while you were at your new hotel. I asked the old ones there about you. I found an old woman who knew your family. They are all in India, like you have said. They all fled when the last rebels were destroyed. Except you stayed. You came to town. You were made the head of the agricultural collective. A teenager, as head of the collective. Who appointed you?”

“You’re a fool. I don’t have time-”

With a single powerful swing of the iron Jomo smashed the back window of the sedan. “Who appointed you?”

Shan took another uneasy step toward the pool of light by the sedan. Jomo was drifting far from their agreed script.

“I can have you back in the gutter by tonight!” Tsipon snapped.

Jomo inched forward, heaved the iron again and smashed the rear passenger window. “Who appointed you?”

Tsipon backed away toward the door he had come in, seemed about to flee when a long iron rod, one of the scraps Jomo kept for repairs, materialized out of the darkness, pressing against his belly.

“I remember your family,” came a raspy voice. Gyalo stepped out of the shadows, using the piece of iron like a staff for support.

The color drained from Tsipon’s face. “You were dead!” he gasped.

Shan took another step forward, prepared to leap between Gyalo and Tsipon. Jomo had dropped Shan off at the municipal building, with instructions to meet at the infirmary, but he had obviously sensed Shan’s intentions, and taken a detour to the stable. Shan never would have expected Gyalo to have enough strength to reach the warehouse but Jomo’s words seemed to have given him new life.

“Good, simple people,” the former lama continued, both hands grasping the iron rod. “They tended the wounded, gave us milk and meat when they had some to spare. They had boys, two adolescents and a teenage boy I recall, all of whom helped, even in bringing in the bodies of our dead to the hiding place below the glacier, where I helped prepare them for the next life.” The old Tibetan stood tall and straight. He seemed to have lost several years of age.

“You were nothing but a beggar with a baby boy when I found you,” Tsipon continued, “both half dead of the cold. I gave you life.”

Gyalo’s hoarse laugh ended in a hacking cough. “I was a business proposition for you. You needed a floor show, a clown to attract customers to your new tavern.”

As Tsipon took another step toward the door the iron rod slammed against his leg, nearly knocking him off his feet. “There was only one person who wielded political power in this county when you were made head of the collective,” the former lama observed. “You were doing business even then, even as your own family was fleeing to be with the Dalai Lama. You gave Wu the resistance fighters and she gave you a prestigious appointment.”

“I told you it was Ama Apte. She traded her village for-” Tsipon’s lie died away as Shan finally stepped out of the shadows.

“It is possible,” Shan said, “that a man of your particular talents might have found a way to survive even when the people in this county finally learn who betrayed them that day. You could always find another lie, offer more jobs to quiet them down.”

“Exactly,” Tsipon said, as if Shan was offering to mediate. “You understand these things, Shan, you’re from Beijing. Tell them. The Youth Brigade was always going to win. I had nothing. It was over. Why shouldn’t I try to salvage my life? Everyone had to pick up the pieces and move on.”

“Everyone else helped their families and the monks,” Jomo pointed out. “You helped the Youth Brigade.”

Tsipon glanced uncertainly at the mechanic, then turned to Shan as if for help.

“For you it was always about business, like Gyalo said,” Shan said. “Back then, and the day Minister Wu died.”

Tsipon inched toward the door. “All that is over with. They have their murderer. I’m a witness, you know. Interfering with a witness is a crime.”

“What I couldn’t understand was how you knew Megan Ross was going to get into that car with the minister, that she was going to reveal her discovery that Minister Wu was also Commander Wu of the Hammer and Lightning Brigade if Wu did not stop her development plan. But then I realized Ross had told you about it herself. You had been with Tenzin and Ross one night at the base camp, and she had told you about her plan. She trusted you, because you had helped with her clandestine climbs. Except Ross didn’t know your own connection to the Hammer and Lightning Brigade, didn’t know that exposing Wu would most likely mean exposing you. And in any event you recognized that Ross was going to destroy all your own business plans. The international community would never deal with Minister Wu once word leaked out. She would be ruined as Minister of Tourism, she would have to resign. The Compact would have instant credibility. Not only would you lose your protector in Beijing, you would lose the expansion of your hotel, probably lose business because of decreased climbing expeditions.

“Ross must have spoken to Wu at your hotel, maybe gave her a glimpse of one of the old photos that you had tried to keep out of the library, to convince Wu to let her ride up the mountain with her. But the minister didn’t get in the car right away, she ran up to her room. Because she had to get the gun she had borrowed the night before, to gibe her old lover Colonel Tan. She was going to kill Ross. But since you were there, she told you to do it.”

“Me? Why would I be there?”

“Because you had your own private business with Wu. You had to speak about her secret stake in your guesthouse, about how she was going to block applications for any other new hotels and grant you an exclusive license to supply the trekking parties.”

“The high altitude has finally baked your brain, Shan.”

“Megan Ross didn’t understand that everything you did was a negotiation. You didn’t help her because she was a pretty American, you did it because she could help you with your business. She moved money in and out of China for the expeditions she worked on. You asked her to leave some outside of China, in Hong Kong, in a special account. She mentioned it in her journal, the day before she died. She was going to look into the reason for your request. She might have already found out,” Shan ventured, “that the account was in the name of Minister Wu. It would have taken one phone call to Hong Kong.”

“She never said anything to Wu-”

“So you werethere. She never had time to say anything because Wu had already decided she had to die, for exposing her role with the Red Guard. But you realized as soon as you pulled the trigger that by forcing you to shoot the American Wu was making you a slave, not a partner. You knew difficult questions would be asked about an American who died in the minister’s presence. If the questioning grew too difficult she would have given you up as the killer, would have exposed you as the traitor to the Dalai Lama’s fighters.”

Tsipon seemed to shrink. He looked at Shan as if he was the only one who could understand. “She always wanted more. First it was ten percent of my new hotel in exchange for the permit, then when she arrived at the hotel she demanded twenty percent of the expanded hotel. She was always the commander and everyone else a lowly soldier. I worked on that hotel for years. But that morning she called it herhotel.” Tsipon looked forlorn, though not beaten. He looked at his watch. “I’ll be missed. The trial is about to start.”

“We’ve already started the trial, Tsipon.”

“What are you talking about?”

“For the real murderer of Minister Wu, and the one who arranged the murder of Director Xie of Religious Affairs.”

Tsipon took a quick step toward the door and grabbed a large wrench from the workbench, slamming it down on Gyalo’s restraining rod. He reached the door, flung it open and froze. Two Public Security soldiers stood in the entry.

He looked back toward Shan, real worry entering his face. “What is your game, Shan? You have no authority.”

Shan stepped to the light switch by the garage door and illuminated the bay. The color drained from Tsipon’s face as he saw the diminutive woman sitting in a chair by the rear wall.

“I think you know Madame Zheng,” Shan observed. “Surely someone in the Party must have told you she is the presiding judge of the tribunal? Did you know she has been visiting your office in your absence, looking at your records?”

Tsipon hesitated a moment, unable to disguise his fear now. “You have no evidence!” he snarled at Shan.

“We have your own words explaining your motive.”

“What I said was nothing!” Tsipon glanced uncertainly at Jomo. “Give me the keys! I’ll drive myself.”

Jomo did not move.

“Shooting Tenzin in the chest, like Ross,” Shan continued, “must have seemed like an inspired trick at the time. If you were to substitute the bodies, the new victim would have to be shot, since the soldiers had already reported two dead of bullet wounds. But you had thrown Tan’s gun away before you encountered the mule on the trail. The holes you left in Tenzin’s chest were huge, no match for any weapon Public Security was familiar with. Forty-five caliber, the Americans call those bullets, big enough to stop a horse. Or a mule. No one here would have such a weapon. It was an impossibility that Cao chose to ignore in order to make his case. But Megan Ross explained it all to me.”

Tsipon grew pale. “She’s gone. You never spoke with her.”

Shan reached into his pocket and produced the folded photo he had taken from Ross’ gau. “She had taken this with her to prove you were connected to Wu, as leverage to get both of you to listen and comply with her terms. She didn’t know she would be implicating her own murderer.” Shan held the photo up for Tsipon to see. The Tibetan reeled backward, as if losing his balance.

Shan tossed the photo on the hood of the car. The People celebrate the final victory in Shogo, said the caption. Names were printed below. A much younger Tsipon was there, with Wu and two other officers. Each face was upturned as they fired into the sky. Each held a heavy pistol, a forty-five caliber, captured from the American stockpiles.

“You can’t prove I was there with Wu!”

Shan gestured into the shadows and the young patient from the infirmary emerged. “You thought all the soldiers involved that day had been reassigned, unreachable. But one was forgotten, because he was sent for medical treatment. The corporal was the driver of the bus, and bravely walked up to the murder scene despite his wounds. He saw much that day. It was negligent of you not to arrange his transfer too.”

Shan had warned the soldier to keep quiet, to let Tsipon assume he could testify not only about Megan Ross being killed, but also that he had seen Tsipon at the scene.

“And we mustn’t forget that account you set up for the minister.”

“Speculation. You have no idea-”

“You probably weren’t aware that there are special anticorrup-tion protocols with all the banks in Hong Kong. You should have chosen Singapore. Madame Zheng will have all the names on the accounts by tomorrow.”

“That was business as usual for people like Wu,” Tsipon protested. “You know Beijing, everyone-.” Tsipon’s words died away as he looked at Madame Zheng, Beijing’s special emissary.

There was movement behind Tsipon. The two soldiers were at his side now. One glanced at Madame Zheng, who nodded, then began fastening manacles around Tsipon’s wrists.

“You killed them,” Shan said, “you killed them both and let me be dragged away to take the blame.”

“You’re nothing but a gulag convict,” Tsipon muttered. “Worthless to society. They were always going to take you for something.”

Strangely, Tsipon tested the manacles, stretching their short chain tight as if he did not think they could be real. His expression as he looked up at Shan wasn’t anger but stunned disbelief. “They can’t run the mountain without me,” he ventured in a hollow voice.

“Negotiate, Tsipon,” Shan offered. “Keep negotiating. The government’s priority is to pursue every scent of corruption, especially when high levels are involved. A new murder trial would be messy since Americans would have to be brought into it now. Madame Zheng came here not for the murder, but for the corruption investigation against Minister Wu. Who knows? You may have a chance to escape a bullet if you cooperate on the corruption charge and give evidence against those truck drivers.”

“Once every Tibetan in this county wanted her dead,” Tsipon said to the floor. “They would have stood in line to pull the trigger.”

More officers appeared, guns at the ready, eyeing the Tibetans suspiciously. Madame Zheng snapped a command and they lowered their weapons, then surrounded Tsipon and turned him toward the door. “They can’t run the mountain without me,” he repeated in a bleak voice as he was led outside. They were the last words Shan heard him speak.

Shan turned to speak with Madame Zheng, but she was gone. He found her in her limousine, the rear door open, waiting for him. “I need a report from you,” she declared after he climbed in and the car began to move. “The kind you would have written ten years ago.”

“I was sent to the gulag for writing reports like that.”

She looked him over. “There’s nothing more we can do to you.” For the first time Shan saw the trace of a grin on her face.

“Cao will not like it.”

“Major Cao will be returning to Lhasa within the hour.”

Shan looked out the window and considered her request. “I need doctors, real doctors,” he declared. “I want one to be sent to Tumkot village, to care for a woman who was stabbed. I want another one sent to the yeti factory. I will give you the patient’s name. And the monks from Sarma gompa. I want them all released.”

Madame Zheng extracted a small tablet and began to write.