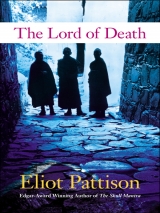

Текст книги "The Lord of Death"

Автор книги: Eliot Pattison

Жанр:

Полицейские детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

Chapter Ten

He stopped the truck at the crossroads where Xie had waited that morning, looking in the dusk for signs of the director’s watchers. The local people would descend on the ruins after Xie and his men departed. There would be prayer stones to retrieve. Even smashed prayer wheels would still be considered sacred. The Tibetans would know that the government tended to return to such sites, with excavators, to remove every stone, to scour the site to bare earth and salt it so nothing would grow. But that would be in the daytime, and in Tibet, everywhere but the cities, the night belonged to the Tibetans. He waited for five minutes, seeking signs of watchers, then turned onto the valley road.

The weathered, compact structures of the gompa were gone. Three thick stone walls alone remained standing, their soot-stained murals exposed to the elements. Everything else was leveled, reduced to a rubble of stone, plaster, and wood. Chairs and tables lay in splinters, smashed not only by the bulldozer but by what looked like sledgehammers. Shreds of old tangkapaintings trapped in the rocks fluttered in the wind. There was no sign of any Tibetans. Then he paused, seeing why no one was salvaging anything. In the shadow of the trees at the far side he could see the low, dark shape of the director’s sedan.

He wandered into the rubble without conscious thought, numbed again by the devastation, vaguely aware of a rhythmic, metallic rumble, the sound of an engine straining, revving then ebbing. He walked past a patch of whitewashed stones that marked where the old chortenshrine had stood, passing a futile moment searching for the bronze or wooden box with relics that would have been secreted inside. Then he stepped toward the sound of the engine, past the three standing walls that had been too thick to topple, to the rock face that defined the back of the compound.

The small bulldozer had been aimed at the Buddha painted on the rock face. Driverless, its engine was on, but something in its drive gears had broken so that it was pushing forward several inches, hitting the rock face, revving and falling back, repeating the process over and over. With new foreboding, Shan looked about the compound for any sign of the driver, then approached the machine, intending to switch off the ignition. Two steps away he froze. The levers that controlled the steering had been fastened in place, tied with old khatas, white prayer scarves. As he reached for the ignition a splash of color by the blade caught his eye. He looked at the scrap of red fur with a vague sense of recognition, not seeing the blood and fragments of expensive overcoat until he was inches away. He staggered, bracing himself against the rock wall, fighting a spasm of nausea. Caught between the rock and the heavy metal blade was a different, bloody rubble, the remains of Director Xie of the Bureau of Religious Affairs.

He did not know how long he stood against the wall, gripped by horror, but eventually he turned and switched off the ignition, using his knuckles on the key so as not to leave prints. He covered what was left of Xie’s head with a scrap of tangka. The Radiant Light of Pure Reality, said a prayer on the scrap, from the beginning of the Bardo death ritual. The words stopped him. Xie might have been a wheelsmasher, might have come to the county to enhance his reputation at the expense of the Tibetans, but no one deserved such a fate. “Recognize the radiant light that is your death,” he murmured, continuing the rite, “recognize that your consciousness is without birth or death.”

He searched the grounds in the dusk, trying to understand how Xie could possibly have let himself be alone with his killer, half expecting to find the bodies of one or more of his deputies. But there were no other bodies. As darkness fell he found a hand lantern in his truck and searched Xie’s car, finding nothing but a box of ritual tools that he removed to the hidden trail at the rear of the gompa. Then he methodically paced along the packed earth.

It was crisscrossed with tire and boot tracks, probably of more than two dozen different people and half a dozen vehicles. He wandered a few paces up the pilgrim trail, where he knew many Tibetans had traveled that day. If they had seen anything they would be burrowing deep into the hills by now.

Shan did not hear the approaching vehicle until it was too late to hide. It came rolling into the compound with its lights out, coasting the last hundred feet with its engine off. He switched off his own light and took refuge in the deeper shadow of one of the standing walls.

“ LaoShan?” came a nervous voice from the dark, a respectful call in Chinese, as lanterns were lit from the road. Shan stepped toward them to find a small pickup truck overflowing with Tibetans, most of them porters from the base camp. In the back of the truck were shovels and a wheelbarrow.

They would not be dissuaded from their salvage efforts, not by Shan’s warnings, not by being shown the grisly remains in front of the bulldozer. These were men who had been hardened by the mountains, who were no strangers to death, and their reverence for the objects that might be buried in the rubble overcame all fear. This was how they preserved their faith.

“Quickly,” Shan urged at last, “let us move the trucks so the headlights light the rubble. If you have canvas, cover the murals. Those walls may yet survive.” Giving up all hope of finding evidence of Xie’s killer, he worked with them for an hour, uncovering many more ritual implements, intact robes, even some costumes used in religious festivals. Some were tied into larger bundles and set on pack frames that several men carried up the moonlit trail. Others were piled on the trucks.

They were sorting through the rubble, retrieving every stone inscribed with prayer, when the man left to watch the road whistled. The lights were extinguished and they watched with rising fear as a single headlight wound its way up the road. The Tibetan on the battered motorcycle had barely dismounted when he was told the news of Xie’s murder.

“The death demons are out this night,” the newcomer said in a hollow voice. “In the mountains. In the town. It will mean the end of us.”

“The town?” Shan asked.

“The knobs attacked Gyalo. When they finished they threw him in the gully with all the other ghosts.”

Nearly an hour later Shan climbed off the back of the motorcycle a block from Gyalo’s compound. The shutters of every house on the street were closed, every gate and door shut fast. Shogo town was bracing for a storm.

The storm had already struck at the old farmhouse of the drunken lama. Half the contents of the household were strewn about the courtyard. The house itself had been attacked. Something heavy, a sledgehammer perhaps, had slammed into the plastered walls, the window sashes, the door. The brittle plaster had shattered and fallen, some hanging loose on the horsehair that had been mixed with it in another century. The windows were nothing but splinters of wood and shards of glass. The door dangled on its bottom hinge. Inside, the two wooden chests that Gyalo had kept his clothes in had been reduced to fragments of painted wood, their contents scattered across the stone flags of the floor. The acrid scent of sorghum whiskey hung in the air from a jug smashed against the wall.

He retreated slowly, watching the street for any movement, then approached the shed at the edge of the dump pit. He had nearly reached the decrepit little structure when the sound of voices caused him to dart into the shadows behind it. He edged along the walls until he could glimpse the speakers.

Kypo and Jomo stood at the lip of the low cliff where trucks dumped their loads of garbage, studying the shadows below, speaking in low, worried tones as the odor of decay wafted up from the pit. Shan glanced inside the shed before approaching the two men. The inside walls were bare, the packed earth floor empty. The artifacts Gyalo had secretly hoarded there were gone.

The two men greeted him with silent nods, and the three stood wordlessly, staring into the shadows below.

It was Jomo who finally broke the silence. “It’s how you destroy infestations of insects, my father used to say,” Gyalo’s son said in a mournful voice. “First dig into the heart of the colony. Destroy them by the thousands at the heart, collapse every chamber they live in. Expect it to take a long time because you will find colonies hidden in the most unexpected places. But eventually there will be only a few left, surviving alone, and when you find them smash them hard, leaving only little greasy stains on the floor.”

“We have to get him out,” Shan interjected. “We can’t just. . ”

“They beat him before they threw him over the side,” Jomo said in a desolate voice. “Hard to tell, though, how many of the broken bones and cuts were from the beating, and how many from the rocks they threw him on.” He glanced at Shan with a grim expression. “Being drunk probably saved him, kept his muscles relaxed, kept him from fighting back, from trying to move and making his injuries worse.”

“He still lives?” Shan’s question came out in a hoarse whisper. “Where?”

“He lives for now,” replied Jomo. “Gone from town. Where no one will ever expect him to be,” he added with a glance at Kypo.

Shan looked back at the shed, noticing for the first time the three bulging burlap sacks near the gully’s edge. Jomo seemed about to block Shan as he stepped toward the sacks, but Kypo restrained him with a hand on his arm.

The first of the sacks was stuffed with prayer wheels, all of which were damaged, some crushed nearly flat, like tin cans being sent to a dump. The second ritual implements, many bent and disfigured. The third held old barley hooks, many of the sickle-like blades corroded and pitted. Shan rubbed his fingertips over the blade of one, then extended it into the moonlight. He could barely make out the crude outlines of mountains, Tibetan script scrawled underneath, too dim to read. “What are these marks?” he asked. “Why do they scare everyone?”

“What does it matter now?” Jomo shot back. He was growing more nervous, casting worried glances toward the street. “If Public Security comes back it will just infuriate them more to find these.”

“Because it could be why he was attacked,” Shan quickly explained what he had learned about the barley hook at the bus ambush.

“It doesn’t matter,” Gyalo’s son replied, lifting the sack with the hooks. “We just know it won’t happen again.” He began to swing it, to throw it deep into the darkness below.

Shan touched his arm. “No. I have a better place.”

“There is no better place,” the Tibetan said in a bitter tone.

“For your father’s sake. He wanted them preserved.”

“So I should trust you?” Jomo snapped. “It was your kind who did this to him.”

Shan did not reply but hoisted one of the bags to his shoulder and turned to the short trail to the stable.

At first the two Tibetans did not want to enter the old stable at the mouth of the gully. They had climbed down the trail in silence, each carrying one of the heavy sacks over his shoulder but Kypo and Jomo set theirs down at the door when Shan stepped inside to light a lamp. Though they had both been there before, it had never been at night.

“They say this place is haunted,” Kypo said hesitantly. “They never did recover all the bodies from the old gompa.”

“One thing I can tell you for certain, Kypo,” Shan said as he began to drag the sacks inside. “All the dead are on our side.”

Kypo muttered something that sounded like a prayer and picked up one of the sacks, followed by Jomo. Shan lifted his lamp and led them past the stall with his sleeping pallet, through the decrepit stable into the adjoining storage room, its roof hanging by only a few beams, roof tiles littering the ground where they had fallen through. He handed the lamp to a confused Kypo, then knelt, running his fingers through the layer of loose earth on the floor until he found what he was looking for, the buried edge of a canvas sheet. He gripped one edge of the sheet, hands on two corners, and slowly flipped it, exposing a hatch of wooden planks bound with heavy iron straps, a recessed iron ring near one edge.

A gasp of surprise escaped Jomo’s throat. Kypo silently bent to help Shan lift the hatch. “The gompa was here for centuries,” Shan explained, “giving them lots of time to construct tunnels and secret escape routes and passages to secret shrines.” He carried the lamp down the steep stone steps, set it on the workbench built along the wall, then reached up to help the Tibetans lower the sacks into the chamber.

“Ai yi!” Kypo exclaimed as he stepped down the stairs. The demons painted on the facing wall centuries earlier were still vivid enough even through the layers of soot to have their intended effect.

“They thought they had pushed all of the gompa into the gully,” Shan explained as he lit another lamp. “This was just an old stable, and the bulldozers couldn’t get down the steep slope to touch it. The stable was used as a granary when the army had a garrison here, then abandoned when they moved on. I wouldn’t have even known about this chamber if I hadn’t dropped a piece of firewood on the floor one night and heard the hollow sound of the hatch.”

Shan held the lamp near the wall, exposing a savage head with horns and fangs. “Like many of the old gompas, its first chambers were underground, built into the wall of the gully. This was a gonkhang, a chapel for protector demons. They often built them in hidden places, using them only for special rituals or for testing the fortitude of novices.”

When he turned Gyalo’s son had the second sack in his hand and was staring at the workbench, which held artifacts in various states of repair. “You’re digging these up,” he said in a spiteful voice. “Every Tibetan for fifty miles is scared to go into the gully so you just go in and help yourself.” He lifted a figure of a deity mounted on a tiger. “These make a big profit on the international market, I hear.” He lifted one of the sacks over his shoulder as if to take it back outside. “You must think us such fools, bringing you more inventory to get rich on. You Chinese always want to just have your way with us!” He took a step toward the stairs, then paused, looking at Kypo, who was stroking the head of the Buddha Shan had been working on when he was not cleaning the printing blocks in the stable above.

“These things don’t belong to Western collectors, just as they don’t belong to the government,” Shan declared. “They belong to the reverent.” He lifted one of the bags from the floor and stuffed it onto one of the storage shelves carved out of the living rock at the back of the chamber. Kypo watched him without expression, then placed his hand on the bag Jomo had thrown over his shoulder.

“You’re a fool to trust him,” Jomo spat, but did not resist when Kypo took the bag from him.

“What he is doing he could be arrested for,” Kypo observed. “The restoration and distribution of such artifacts is regulated by the Bureau of Religious Affairs.”

“So what?” Jomo shot back, “he is already a criminal, already an illegal.”

Kypo stuffed the bag beside the first one then turned to Gyalo’s son with an impatient frown. “So now he has shown us his secret. He has put himself at risk of arrest in order to save the old things.”

Jomo’s protests began to fade away as he examined the work Shan had been doing. When they finished stowing the sacks, Kypo stood in front of a dirt encrusted painting of a ferocious deity with a horse head. “There could have been other hiding places,” he said. “Why show us this one?”

“Because it is the best of the hiding places I know. I don’t want it forgotten for another fifty years.”

“You sound like you are going away.”

Shan too gazed for a moment at the deity before replying. “I am always going away,” he replied. It was, he had realized years earlier, the only way he could survive, by not lingering anywhere too long, by living on the fringes, out of sight of the government.

Kypo reached into one of the sacks and pulled out a corroded sickle. “It is a symbol from the war,” he explained as he pointed to the marks on the blade. “The resistance didn’t have many weapons. They used farm tools when they had to. The army of Tibetan fighters had a name. Four Rivers, Six Ranges, it was called. The soldiers liked to scratch the name on their weapons. Some of the units had modern weapons but still carried the blades as symbols, like badges of honor.” He looked at the deity on the wall. “It’s just a sickle. Tools are in short supply. It was a just a blade they used to cut the ropes. Finding it at the ambush doesn’t signify anything,” he said to the horse-headed god on the wall, as if trying to convince it.

But it did signify something, Shan knew, and it was why the porter had been frightened when Yates described it. The sign on the sickle had been used by resistance fighters decades earlier, and the ambush on the Public Security bus had been an act of resistance.

Half an hour later, as Shan walked along the street outside Gyalo’s compound, weighing his growing suspicion that it could not have been Public Security who attacked Gyalo, a familiar red vehicle rolled to a halt beside him. Nathan Yates stepped out, wearing a haunted expression, and blocked Shan’s path.

“It was poetry,” the American declared in a hollow voice. “She carried a book of Buddhist poetry in her pack and would read it by candlelight up on the mountainside, because it is a Buddhist mountain. She would write out the poems sometimes and hide them under stones. It was one of her favorites, a death poem by a Japanese poet.” As he looked up toward the stars his voice dropped to a whisper. “Is it me the raven calls,” he recited, “from the world of shades this frosty morning?”

“She died well,” Shan said softly, realizing that Yates’s acknowledgment of her death was releasing his grief. But the American did not express his sorrow in silence. Shan leaned against the car and listened as Yates quietly spoke of climbing with Megan Ross, of mountains they had conquered together, of the great spirit that welled up within her when, in her phrase for reaching a summit, she touched the sky.

“Porters came in with the news of the murder at the gompa,” Yates finally announced, in a louder voice. He gestured Shan toward the front seat of the car.

“There’s nothing I can do,” Shan said, glancing toward the mountain road. He prayed that the Tibetans he had left at Sarma had taken his advice and stayed no more than another thirty minutes before leaving with their artifacts and returning the truck to Tsipon’s compound.

“If I don’t get my expeditions staffed they will pull my permits.”

Shan paused, trying to connect the American’s words.

“Those porters who returned when Tenzin’s body was found are disappearing, back to the village. No one will speak with me. If it was just about money I could go to Tsipon. They know Public Security will swarm over the slopes when they learn of Director Xie.”

“You should go to Tsipon in any event.” Shan began to back away.

“Not for this. One of the remaining sherpas says everyone is gathering in the village square, asking for the astrologer to read the signs. I saw Kypo speeding away, back toward the village. They are bringing things to use as weapons. They say what Tenzin is doing shows how angry the mountain is.”

A chill ran down Shan’s spine. “Tenzin is dead.”

“A villager came into my tent before he left. It scared the hell out of me. He said Tenzin keeps trying to rise up to serve the mountain and someone keeps killing him.”

The snowcapped peaks were like silver islands, under stars as thick as pollen. Yates drove slowly up the treacherous, twisting road, slamming the brakes more than once as the small nocturnal mammals of the mountains hopped across their path. Shan began to urge the American on after one such stop when he saw that Yates was staring uneasily at the village on the slope above. Tumkot was strangely glowing, launching its own flickering stars into the night sky. A huge fire was burning in the square.

“What if it’s Tenzin’s funeral pyre?” Yates asked. “We’re not going to be welcome.”

“They wouldn’t place a pyre in the town square,” Shan said, though he still directed Yates to extinguish the headlights. For the last half mile he walked in front of the truck, guiding it forward with the American’s hand light. They left the truck a hundred yards from the village and approached on foot, Shan guiding Yates through the dim alleys and stairs. Twice they flattened against alley walls to avoid being seen, once for two men carrying pitchforks as they marched down the main street, then for a woman who hurried by with a length of white cloth and a bucket of steaming water.

Two ghosts waited at the rear of Kypo’s house, glowing in the moonlight. Neither the long-haired white goat nor the girl, who was wearing one of the white T-shirts handed out in expedition camps, uttered a sound, just watched with fearful expressions as the two men entered the back door.

Inside, beside the ground-floor stalls, Kypo stood at a makeshift table on which a body covered with a blanket lay. “Are you crazy?” he growled as they emerged from the shadows. “Do you have any idea what is going on in the square?”

“Public Security doesn’t know about Xie’s death yet,” Shan pointed out.

“It’s not about Xie, it’s about the original murders. Cao has decided he needs additional witnesses. A convoy is getting ready at the garage in town, with maps for Tumkot.”

Shan refrained from asking how Kypo had learned such a well-guarded secret. They both knew someone who collected secrets at town garages. Kypo and Jomo seemed to be forgetting the grudge that had stood between them for so long.

“They will seal off the roads in the morning, order every man, woman and child to assemble in the square. Anyone without papers will be arrested. But that’s not why the porters refuse to work,” Kypo added, pointing at the body. “That’s why. They say his soul is being beaten to a pulp. Every time the goddess tries to take him he is killed again.”

Shan stepped closer to the table. The incense that burned at each end traditionally was for attracting spirits. But Kypo had increased the usual measure because of the smell of decay. Though the body had been in cold storage much of the time, it had been more than a week since Shan brought it down from Chomolungma.

“I can’t be responsible for what they might do if they see you touching that body,” Kypo warned. “It’s been cleansed.” A shadow emerged out of the darker shadows. Kypo’s wife came to his side, her face tight with fear.

“What do you mean he is killed again?” Shan asked.

It was Kypo’s spouse who answered, her eyes flaring for a moment as Shan took another step toward the body. “Bones, heart, head,” she said, her voice heavy with warning.

Another figure appeared, silhouetted in the doorway to the street. The hulking blacksmith, the second husband of the household, cursed and made a quick lunge at Shan. His fist was blocked by Kypo’s raised arm.

“I was taking him on his passage,” Shan declared in a level voice, “before half the people of Tumkot even knew he was dead.”

The blacksmith shoved Kypo back and took another step toward Shan, his hand reaching for a hammer on his belt. “He is the one who brings them back when they die,” Kypo called out. “Shan knows the words to say. He wears a gau. He was a prisoner of Major Cao,” he added, struggling how best to explain Shan.

The big man’s arm swung up again, but more slowly. Shan did not move as the man pushed open the top of Shan’s shirt and pulled out the prayer amulet hanging from his neck. The blacksmith’s face wrinkled in confusion. He did not protest when the wife of the household pulled him away, back into the shadows.

“I explained already that his bones were broken in the fall, that the holes were put in his chest by the knobs,” Shan said to Kypo.“Those are the explanations for what happened to his body.” But what had Kypo’s wife said? Bones, heart, head.

The Tibetan just stared wordlessly at Shan, as if to say Shan did not understand.

Shan, more confused than ever, pulled the blanket back to expose the upper torso. “The body was given to me on the trail above the road to the base camp. I helped wrap him in canvas and tie him to the mule.”

Two Tibetan women appeared, carrying tormaofferings, little deities shaped out of butter. As they positioned themselves beside the body, a teenage boy appeared, anger in his eyes, holding a staff before him as if to threaten the two outsiders

“Megan!” Yates suddenly exclaimed, then quickly lowered the pack on his back, extracted his small computer and set it on a half wall along one of the stalls. A moment later its screen began to glow and he started scrolling through lists of files.

Shan eyed the gathering Tibetans behind Kypo. There were more than ten now, all watching him with intense distrust, several holding objects that could be used as weapons.

Yates, oblivious to the hostile, expanding crowd, tapped on the keys of his computer. “Megan has. . had a special technique she used to weed out the climbers she thought wouldn’t make it to the top. She kept a file in her computer of photos. On any expedition she was affiliated with she made sure everyone saw them before they climbed above base camp.”

“I don’t understand,” Shan said.

The American gestured Shan toward the screen with a grim expression. “The dead,” he said in English. “She collected the dead.” Yates began to scroll through a series of macabre photographs. “According to this, Tenzin was the twenty-fifth dead climber she photographed.”

With a shudder Shan recognized the sherpa. He had gone up to the advance camps himself only once, but it had been high enough to see three of the gruesome figures frozen to the mountain, slowly being covered with snow and ice. He glanced up at Yates in confusion. The image on the screen was simply Tenzin in repose, his body laid out at the base of the rock face from which he had fallen.

“I looked at it the day you took Tenzin away,” Yates explained. “My gut said there was something amiss, but I couldn’t find it.”

It took Shan a few seconds of silent searching to find the answer. With new foreboding he pointed to Tenzin’s feet.

The American sagged. “Damn it, no,” he moaned in an anguished voice. “Not Tenzin.” It was indeed as if Tenzin had just died again.

“What is it?” Kypo demanded over his shoulder.

“The boots,” Shan explained.

“They’re backward,” Yates said. “His climbing boots are on the wrong feet.”

“But what does it mean?” the Tibetan asked.

“It means he was murdered,” Shan said. “I should have seen it,” he said, anguish now in his voice. “If I had seen it I might have. . ” His words drifted off. Done what? Shan himself felt like one more victim running before the deadly avalanche let loose the day the minister died. No, he chastised himself as he turned back toward the body, these villagers deserved the truth. He knew now the avalanche had started with Tenzin, not with the minister. “What it means,” he said, “is that it was not the hand of the mountain that killed Tenzin, it was the hand of a man.”

“Who here is his family?” Shan asked after a moment.

“A sister is here, with her son,” Kypo said, gesturing to a woman in her forties and the teenage boy who wielded the staff. “His mother is on the other side, in Nepal.”

“They must roll him over,” Shan said.

“He’s been cleansed,” the sister protested. “Purified for his passage on.”

“And what kind of passage will that be,” Shan asked, “if we cannot send him with the truth? I need to turn him over. You saw something when you cleaned him, evidence of the third killing.”

The woman searched the confused faces of her companions then gestured for Kypo, not Shan, to help turn the body over.

Bones, heart, head. At first everyone had thought he had died from the fall that had crushed so many bones. Then two bullets had been shot into his heart. Shan investigated the third killing of Tenzin by studying the back of his head.

Somehow murder always seemed abstract to Shan until he saw the sign of the deathblow. A dark, empty thing began gnawing inside him as he gazed at the mark at the base of the sherpa’s neck, but the foreboding was quickly replaced by shame. He should have known. He had failed Tenzin, and by doing so had given room for the murderer, then the knobs, to play their games with the people of the hills.

After a moment he spoke into Kypo’s ear, then waited as Kypo disappeared, the Tibetans getting more and more restless, until a minute later Kypo returned from his supply stores holding a foot-long steel pin, pointed at the bottom.

Shan took the pin and extended it for all to see, then pushed back the thick hair at the base of Tenzin’s neck. “He was sleeping at his new advance camp. There’s enough soil and gravel there to use tent stakes like this. Someone came up and sank this one into the back of his neck. It was over instantly-no blood, no pain. Then the killer pulled him from his sleeping bag, dressed him, in his haste putting the boots on the wrong feet, and dropped him over the side.” He glanced at Kypo. “Using a frayed rope certain to break to complete the image of someone who had died in a fall.” It had seemed so obvious that he had died in a fall no one had bothered to ask any questions. Shan looked back at the small puncture at the base of Tenzin’s neck, noticing a speck of soil at the edge of the wound. The pin had probably been taken out of the ground then reinserted after the killer was done.

The villagers reacted as if they had seen Shan himself drive the pin into Tenzin’s spinal cord.

“The mountain people don’t kill each other,” the blacksmith growled. “You outsiders killed him!”

“I didn’t kill him,” Shan shot back, then gestured toward Yates. “This man didn’t kill him.” A man stepped forward, an ax in his raised hand. Yates retreated into the shadows. So much for allies, Shan thought. He eased backward to avoid the man’s swing but then another villager advanced at his flank, his face dark with anger, his hand clutching a short club.