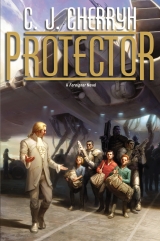

Текст книги "Protector "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

8

Morning brought mail and a last cup of tea to follow the paidhi-aiji’s solitary breakfast. The apartment was very quiet now—not that Geigi had ever made a lot of noise as a houseguest, but the sense of lordly presence in the place was gone.

So was Geigi’s company at breakfast, the distraction of his cheerful conversation on completely idle but interesting topics. That part had been pleasant.

The shuttle was well on its way, safely clear of the atmosphere. Geigi was headed home, and the complex affairs and troubles of the space station had become just a little less intimately connected to the problems of the continent.

That was, over all, a good thing.

So was the quiet, in which he could, at last, think without interruption. They were not necessarily pleasant thoughts, regarding the problem of the Ajuri, and the imminent legislative session with its necessary committee meetings, and committee politics. And there was going to be a question of what he was going to do with guests whose parents had an agenda—

But those were questions he could sidestep. The parentsweren’t coming. Wouldn’t be allowed to come. Just deal with the children as children, don’t let anyone get hurt, and translate for them—Cajeiri’s ship-speak had to be a little rusty after a year—and he was sure he’d be drawn in for all the tours and the festivities, to be surethe guests had a good time.

Of all jobs he had ahead of him—that one might actually have some real enjoyment in it.

Give or take a boy who’d already been arrested by station security.

But that was, he said to himself, possibly Cajeiri’s influence.

He could handle it. Absolutely.

And Geigi by now, thank goodness, understood their earthbound worries, andthe security issues his bodyguard would have explained by now. The paidhi-aiji’s security could protect the kids; the parents were Geigi’s problem.

He had his own share of loose ends to tie up.

The tribal bill. The cell phone bill. He had to arrange meetings, formal and informal, talk to the right people, have his arguments in order, and get done what had to be done before the next shuttle landed and brought him kids who might, on first seeing a flat horizon, heave up their breakfasts.

The cell phone bill was certain to raise eyebrows. Explaining whyhe’d pulled his support from it, and would in fact vetoit—technically, Tabini still granted him that ability, where it regarded human tech—that was going to be the problem with that one. He didn’t want to dust off the veto power. He reallydidn’t. He wanted the atevi to vote it down.

The tribal bill was far from a sure thing, and potentially could blow up. Problems regarding the status of the tribal peoples had hung fire since the War of the Landing, which had displaced the Edi and Gan peoples from the island of Mospheira, and settled them in two separate coastal areas. They—quite reasonably, in his opinion—wanted full membership in the aishidi’tat, and even with the favorable report of the two Associations nearest the tribal lands, they still had some old prejudices to deal with. The most bitterly opposed, the Marid, was going to vote forthe measure: Ilisidihad accomplished that miracle. The southwest coast, Geigi’s district, was going to vote for it; the northern Coastal Association, where the Gan lived, had Dur’s backing, and thatvote was assured.

He just had to budge, principally, the six very small hill clans who sat between Shejidan and the Marid, who had made their living partly from agriculture and hunting, partly from trading, and who, as much as they felt that being ancestrally native to the mainland made them superior to the tribal peoples, believed that the new trade agreement between Ilisidi and the Marid was going to kill off theirtrade with the Marid, and therefore they wanted the tribal bill to fail—so as to make Ilisidi’s trade agreement fall through.

He had an answer for that one, if he could get them to stop shouting and listen. The Marid was going to develop an economy that would flow uphill to them. And the same benefits would be available to them, if they would stop spending all their resources on the Assassins’ Guild and allow the Scholars’ Guild to operate in their districts—which could be said of the Marid as well. Too many of the atevi clans were still mired in their rural past and needed the world perspective that came with education. Thatpart, however, he very much doubted he was going to mention in this session. Several new rail stations, with a favor given their local products bySarini Province, however, might be an inducement.

Bribery? Bet on it. It was a time-honored tradition.

Meanwhile . . .

Meanwhile the mail arrived, brought in by Narani. Jeladi, arriving through the door Narani held open, brought him tea, and both silently vanished.

Lord Machigi’s was the most conspicuous message cylinder. Machigi, in his capital at Tanaja, declared he was writing simultaneously to him, the aiji-dowager—and to the Physicians’ Guild, who had asked access to all districts of the Marid, in another of those many-sided deals.

Machigi pointedly reminded them that he could not give any other guild the access and assurances they wanted until the Assassins’ Guildhad gotten the lords of Senji and Dojisigi to come under his authority. Since those clans had wanted to assassinate him,Machigi understandably and reasonably wanted that to happen. Soon.

He wrote: One entirely understands this reasonable position. The paidhi’s office will explain the urgency to the parties in question.

That was going to have to be his answer to a lot of queries for the next while. The Assassins’ Guild was mopping up its own splinter group in the two districts, and trying to figure out who was a loyal and proper member of their own guild and who was one of Murini’s leftovers—that took some investigation, or there was the possibility of a lethal injustice, the sort of thing that could set back the operation and dry up sources of information. It was not easy to untangle the division that had been building in the Guild for, apparently, decades, before it found expression in an overt move for power. It was particularly not easy since the Assassins’ Guild kept every family secret in the aishidi’tat in its workings, and the rule of secrecy, reticence, clan loyalties, and personal honor were all involved. They werethe legal system, the lawyers andthe judges, the spies, the keepers of personal and state secrets, and they were experts at covering and uncovering tracks.

That was one worry.

Then there was, in a cylinder from the director of his clerical office an advisement that the Tribal Peoples bill had been diverted to the Committee on Finance.

Finance?Damn!

That was a conservative committee. He knew Tatiseigi hadn’t done it. SurelyTatiseigi hadn’t engineered it.

That meant the aiji-dowager urgently had some meetings to organize and some favors to call in. There was nothing, frustratingly nothing, a human could do to aid the bill in that particular committee. Humans were not popular among the conservatives, where the tribal peoples found hardly more welcome, and that meant the aiji-dowager and Tatiseigi had that situation entirely in their hands. They had to get it recommended outof that committee, or it stalled and died.

And the trade agreement with Machigi would likely die with it.

The second letter was a well-timed letter from young Dur regarding plans to integrate the barter-economy of the Gan state with Dur—and by extension, with the rest of the country—via setting up, not a bank, which the Gan would not trust, but an exchange, where both barter and use of coinage could go on side by side. This brilliant plan would be under the auspices of the Treasurers’ Guild . . . assuming the tribal bill passed. The theory was that, while goods were comforting in an exchange, the convenience of currency would win out.

Notcoincidental, that timing. Well done, Reijiri, Bren thought. That item would be extremely useful, in the dowager’s hands, especially now: the Committee on Finance supported the Treasurers’ Guild.

It occurred to him, too, that Lady Adsi, of the Marid Trade Office, might have some useful suggestions on that problem. The Marid had its own difficulties trading with three local currencies, plus barter, and conducting commerce with the rest of the aishidi’tat.

Time being of the essence, he penned a small note to that effect, rolled both letters together, slipped them into one of his white message cylinders and took it directly to Narani to be couriered to the dowager wherever she was at the moment.

Satisfied that he’d done all he could on that front, he returned to his office and three letters from companies seeking a recommendation to Mospheira. He still handled trade cases, mostly by routing them to the appropriate office on the island. He attached notes for his clerical office, and turned to the final cylinder, one in a style he knew well: Ramaso, his major domo at Najida.

Ramaso reported on the construction on the estate, on the road improvement, and on the arrangements for a village wedding he had promised to occur at the estate if they could get the new dining room, hall and sitting room in order fast enough. And the news was good, very good indeed. The work would be completed on time. The wedding was going to happen. That lent cheerfulness to the day.

Ramaso reported as well on the order for wine and food, for his approval.

Granted. It made him particularly happy to keep that promise.

And finally Ramaso wrote that the framework for the new wing was not only up, the paneling was being shaped and carved in situ, and stonemasons were at work.

Excellent news. All of it.

He answered Ramaso, and in the same train of thought, thinking of his last visit to Najida and a particularly painful, several-day cross-country trek in court-dress footwear, he dashed off an order to a shop on Mospheira. He imported his boots, by preference, from an old-fashioned bootmaker up by Mount Adams. He requested another three pairs of boots, one for indoors, one for court . . . and oneof them the stoutest hiking boots possible. Witha metal shank.

After that, he was at leisure to draft routine letters to several of the guilds, official letters to certain legislators regarding personal meetings. . . .

He was actually glad to be back to the routine of his office, even with the tension over the vital tribal bill.

Statistics and statistics. Stacks of financial reports—those were not his favorites . . .

But there were far worse ways to spend an afternoon, and lately, he had seen all too many of them.

9

Life was very much better now, in Cajeiri’s estimation. He had his aishid for company and conversation, and the imminent prospect of his guests and his party.

Training for his aishid in the gym or on the firing range was daily, it turned out, and the place was very quiet when they were gone. But in the evenings, on their little private dining table, Veijico and Lucasi were doing a lot of interesting instruction with the equipment they had brought in.

It was supposed to be just Antaro and Jegari. Cajeiri was not really supposed to hear the lessons, they said, because some of it was classified and it was Guild regulations—the Guild was being very strict about regulations, since the Troubles. But he still heard a lot that was going on, and he already knew how the locators worked, and about wires, and explosives, which he had learned mostly from Banichi, aboard the ship.

Finally they said he was,after all, his father’s heir, and the aiji couldoverride the lesser rules, so they said it was probably all right for him to hear, so long as he did not talk about it with anyone but them.

Electricity became a very fascinating subject—he understood now a lot of things it could do besides turn on lights.

His tutor was willing to tell him a lot about electricity, things which were notclassified, but he began to see how those theories might relate to things that wereclassified.

He had had Banichi and the exploding car in mind, when he had first asked his tutor about circuits.

He really learned about explosives, now, and how Banichi had known how much to use. And he came to realize that explosives were very good if you had a big target, or room enough, but that electricity was more subtle. That was Great-grandmother’s word: subtle.

And most subtle of all were the wires, which could do terrible damage and which atevi were not supposed to have, but they did. They were illegal for anybody but Guild, and that only under very special circumstances and with Guild approval.

He’d known about wires before, but now he knewabout them. He was excited about that.

Lucasi was kneeling on the floor in the bedroom doorway, showing him, with a real wire that was not powered up, how to detect such a trap, telling him where they were most often used, and why—when a knock came at the door.

Cajeiri ignored it, trusting Antaro to see to whoever it was.

She brought back a letter, to the table where they were working, and it was not a regular letter, but one in a plain steel cylinder with just the Messengers’ Guild crest stamped in it, and dented and scuffed as this sort of cylinder often was. It was so odd for him to get such a letter that Antaro insisted on opening it herself, just to be sure.

It was machine-printed, because it had come down from orbit, from Lord Geigi himself.

“To me?” he asked, but he could see it was. A letter directly to him—and saying that his associates from the station were all coming on the next shuttle. Bjorn could not come, but Irene could. And that was the tightest group of them, Gene, Artur, Irene, and him, even if they were an infelicitous number, they had Bjorn sometimes, for a fortunate fifth.

The shuttle was coming early.

Electricity could wait. He had to tell his father immediately, even if he was sure it was not the only letter from Geigi that would have come to the door. If he hadreceived any information his father had not, he had to be prompt in reporting it, and just—proper. He had to be absolutely proper. Proper about everything. And not offend anybody. It was really happening.

His birthday was still days away, and they were coming early and they would have two weeks or however long it took them to service the shuttle before they could go back up to space.

It was happening, it was happening, it was happening.

He put on a better coat, to show respect, and he took himself and his aishid straight to his father’s office door.

“Honored Father,” he said, when he was let in. “I have a letter from Lord Geigi, addressed to me. He says my guests are coming! And the shuttle is coming early.”

His father had a serious, even frowning expression. He realized he had interrupted his father at work, reading his own mail. Maybe coming quite so fast was not such a good idea after all.

Or maybe there was something really the matter.

“We are aware,” his father said, in a flat tone, and he thought it wise just to bow and back out of the room.

“Excuse me, honored Father.”

“The legislature is in session. The tribal bill, nefariously diverted into a conservative-dominated committee, has run into opposition, and your great-grandmother is now asking me to get a letter from the six highland clans giving their support. These six clans cannot agree with each other. How shall I persuade them?” His father pushed back from the desk with an annoyed expression on his face. “Against these other problems, do you truly have a concern, son of mine?”

“Honored Father, only to inform you.”

“Properly so.”

“One would wish—”

“You are about to ask me for permission to go out to the spaceport.”

“One would hope—”

“You will be lodged in your great-grandmother’s care during that visit. What she does I am sure will be out of my hands, so you will have to arrange that with her.”

“One is grateful, honored Father.” It was good news. It was wonderful news.

His father’s expression grew less angry. Slowly.

“You have given no thought, yet,” his father said, “as to where to lodge your early guests before and after. Do you propose to put them into the guest quarters here? Or in your small suite? I do not think that would be the best idea.”

“Honored Father.” He bowed. No, he had not thought about where he was going to put them. He had been trying to think how he could take them to interesting things, or any of those matters. “One thought some things would be planned by staff.”

“My staff is busy. Staff in general is greatly reduced, your mother is having nerves, and a set of foreign children crowded into the guest quarters and trooping through the sitting room will not improve her mood. How will cook accommodate them? How will staff inquire about their needs? One assumes they are no more tolerant of sauces than is nand’ Bren.”

“Perhaps—” He cast about desperately for an answer. “Perhaps nand’ Bren will help. He has a guest room. His cook understands about humans.”

His father hooked one arm about the side of his chair. “A reasonable suggestion. Undoubtedly nand’ Bren will have to assist. So will your great-grandmother be fully capable of handling details. Do not distress yourself, son of mine. I have thought about these things. And the logistics of the festivity itself. One only wondered whether you had in fact devoted any thought at all to the practical matters in this visit. Jase-aiji grew quite ill when he simply looked out over a flat surface. He had all manner of difficulty with dizziness.”

He had not thought about that. He could look like a fool. He was very anxious not to misstep and make his father think he was a fool.

“If I can write to them, I can warn them, honored Father.”

“Your great-grandmother will be in communication with nand’ Bren, son of mine. I am sure he will foresee a great many of the difficulties. Go enjoy the day.”

“Honored Father.” He bowed and started for the door.

And then he had a thought, how everything including himself was being turned over to the people his mother most objected to. He stopped and looked back, catching his father regarding him with a particularly thoughtful look. He bowed. Asked very cautiously: “What does Mother think about my going to Great-grandmother?”

His father let go a deep breath. “She will not be happy. But she would be far less happy at the attendance of three human children at close quarters. The baby is troubling her a great deal.”

“Is she all right?”

“She seems to be. In all honesty, son of mine, I do fear she is not going to be at her most gracious.”

Mother was his father’s deepest problem. He knew things had not gotten better. And he had the feeling that his father was taking fire for him on the matter of his guests. He did not know how to say that in words.

“Shall I go tell her about them coming early, honored Father? And about me going to Great-grandmother?” he asked. “I think she should know it before the servants happen to mention it.”

His father thought about it a moment with that look he used deciding serious, serious things. Then he nodded. “Go, son of mine. If you have learned anything of nand’ Bren’s art, use it.”

“Yes,” he said respectfully, and bowed, and left, back out into the hallway, where his aishid waited.

“I am to see my mother, nadiin-ji,” he said, feeling all the while he was not going to have any good reception, and walked down the hall as far as his mother’s door.

His mother did not like surprises. And he knew for certain that his great-grandmother having his birthday was the kind of thing that would have his mother and his father shouting at each other, the sort of thing that just tied his stomach in knots and scared the servants into whispers.

But he had said it: it would be far worse if his mother was surprised by a servant talking about plans she had no idea about. He gave a tug at his shirt cuffs and at the lace at his collar, took a deep breath and had Antaro knock before he tried the door—it was unlocked—and just went on in.

His mother’s suite, with that beautiful row of windows, and white lace curtains, and the crib where the baby would sleep, seemed an unhappy, lonely place at the moment.

It was one of Cook’s staff who came out to see who had come into in the nursery. That woman, and two of the girls who ordinarily washed the dishes and did sewing, were the only staff his mother had at the moment. His mother was not happy about it, and by their habitual faces, neither were the girls.

“Young gentleman,” the woman said.

“Please tell my mother I am here,” he said in as matter-of-fact a tone as he could manage, and waited to be let into his mother’s sitting room.

The door opened wide to admit him. His mother, wearing a pretty white lace gown, was sitting, reading by the light of a flower-shaped lamp. She folded the book, and looked at him, expressionless as if he were some servant on business.

He bowed. “One wished to tell you without delay, honored Mother. The shuttle schedule is changed. My associates are coming down early, three of them. One is not certain how much early, but very soon.”

“Indeed.”

“One knows you are not happy to have my guests here. Father says I am to go to Great-grandmother and let her and nand’ Bren take care of things and not be a bother to you.” The last part was his invention, which he thought was a good thing to say.

“Sit down,” his mother said, with no hint of expression, and he found a seat on her footstool, and sat quietly. “Are you pleased with this arrangement, son of mine?”

“Yes, honored Mother.” He sat on the very edge of the footstool. Mother was not as good as Great-grandmother about leading one into traps, but one had to be very wary. Great-grandmother just thumped his ear when she was angry. But his mother went on being mad for hours. Days. He really had rather Great-grandmother.

“You think your great-grandmother will be more patient than I am?”

That was a trap. “I think Great-grandmother is not having headaches.”

“One supposes the paidhi will be involved.”

“One thinks, yes.”

His mother frowned. “Could you ever even talkto these people, son of mine? How do you speak to them?”

She had never asked him that. He did not want to admit he was fairly good at ship-speak, though he supposed she was going to find out. “We use signs. They know a little Ragi. I know a little ship-speak.”

“You know it was illegal for them even to speak to you not so many years ago. It was illegal for them to know Ragi at all. And very illegal to speak it.”

He was amazed. “Why?”

She laughed, shortly and not very happily. And he had no idea why. “You arestill young. Ask nand’ Bren someday. He can tell you.”

“I am almost felicitous nine. And I shall be much smarter and not get into trouble this next year.”

“Do you promise?” She reached out and he steadied himself, not to flinch. He had a stray wisp of hair that never grew long enough to go back. She smoothed it back even if it did no good. “I hope your sister’s hair grows to an even length.”

“I put a little goo on it.”

A laugh. Actually a laugh. “I know you do. I am glad you have two servants now.”

He wanted to say, One is very sorry about yours, but he did not want to get his mother off onto that topic. A little silence hung in the air, uncomfortably so.

“So,” she said. “Your great-grandmother will house these foreign children. That should be interesting, amid her antiques. And herstaff will plan the events.”

He saw where this was going. Right then. The piece of hair had fallen down again. He felt it. And his mother reached a second time and put it in order.

“What did you do on your last felicitous year, son of mine? How did you celebrate, aboard the ship?”

“I do not remember that I did at all,” he said, and that was the truth. “Time on the ship gets confused.”

“Your great-grandmother forgot your birthday?”

“Sometimes the ship does strange things. And you lose days. Day is only when the clock says, anyway.”

“So you have had no festivity since your fifth. Do you remember that one?”

“No, honored Mother.”

“We had a very nice party. Flowers. Toys. Very many toys.”

He shook his head. He had a good memory, but sometimes he thought his life had begun with the ship. The memories from years before it were patchy, tied to places he had never been. They told him about his riding a mecheita across wet concrete at Uncle Tatiseigi’s place. And he almost could remember that. At least he had pictures in his head about it, but he could not remember much about the house the way it had been then—only the house when they had all been there, with shells falling on the meadow around it. Most of his memories were like that. They were things that had happened, but he had no recollection of where and nothing to pin them to. It seemed they had been on the train once. He remembered the train. He remembered woods that might have been Taiben on a different trip than when he had met Antaro and Jegari. But he had no idea.

“What would you like for your birthday?” his mother asked him. “Is there any gift you would like?”

He was beyond toys, really. Most of what he liked were books. And he wished he could get the human archive back. Therewere his memories, of horses, and dinosaurs, and humans, all of which would appall his mother.

So he thought of something that would not come in a box. But he did want it. “I want you and Father to be there.”

“Son of mine.” His mother sat looking at him, and did not finish that.

“I wish you and Great-grandmother would not fight.”

“Try wishing that of her.”

He knew nothing to say, to that, because mani was mani and that would never change.

“Well,” his mother said, “you shall have your party here, in the Bujavid. In our sitting room. Your great-grandmother may come. I shall invite her. And the paidhi-aiji. Are there others?”

“My tutor.”

“Not the Calrunaidi girl.”

“My cousin. She would not know anyone. Everybody will mostly be adults. And she could not talk to my guests. And besides, I really do not know her.”

She nodded, not disapproving that information. “Well. A very modest request.”

“I have everything I need. I have my aishid. I have a good tutor. I have my own rooms. I have Boji.”

“That reprehensible creature. Will you take himto visit your great-grandmother?”

“May I?” He was really worried about Boji if he had to leave him. Eisi was a little afraid of him, since he had gotten his finger nipped. “And I know Great-grandmother has servants, but might I take Eisi and Lieidi with me?”

His mother smiled that secret smile she had when something amused her. “Son of mine, this is your household. You may deal with it as you wish. I see I have nothing to do. I leave everything up to your great-grandmother.”

That was down a track he wished she would not take. And there were, regarding her and his grandmother, things he wanted to know.

“What did you talk about?” he asked. “When you walked with Great-grandmother at the party, whatdid you talk about?”

His mother’s face went suddenly very serious. “Things,” she said. “Things that truly are not that interesting.”

“Iwould be interested, honored Mother.”

“Ask her. And when you do ask her, perhaps you will do me a favor.”

“What favor, honored Mother?”

“She offered me staff. And a bodyguard. If you will do me the particular favor, son of mine, tell her a skilled hairdresser who has also had a child would gain my deep gratitude at this point.”

“A hairdresser, honored Mother.”

“Truly,” she said. “Such a gift might win my gratitude. Shall I tell you my logic? It is very simple. The secrets of your father’s household are no secret from your great-grandmother. This is notthe case with other clans who have offered. So tell her yes, I have thought about it. I shall acceptsuch assistance, not the bodyguard, not the wardrobe mistress. I wish to see how a small instance runs, and where man’chi may truly lie.”

“I shall ask her, then, honored Mother. I shall be glad to ask her.”

“I shall be relieved,” his mother said in a low voice, “beyond telling. But if this hairdresser bears tales to your great-uncle, understand, she will regret it—I want nosuch connections. I am trusting your great-grandmother in this one thing.” She made another tweak at the straying lock. It was hopeless. It was loose again in the next instant. “Even your hair is stubborn. Go. Be good. Look forward to your guests.”

He felt good. Truly happy. He had never in his memory had so good a conversation with his mother. But his great-grandmother’s teaching immediately nudged at him to be a little suspicious.

There was oneplace to go with such a confusing situation: man’chi was a clear guide on that matter. When he took his leave of his mother, he gathered his aishid and went back to his father’soffice, interrupting his father’s work one more time.

He bowed slightly and said, quietly, “Honored Father, Mother has asked me to ask Great-grandmother for a hairdresser.”

“Gods less fortunate!” His father shoved his chair back from his desk and looked at him, up and down.

“One feared there might be a problem with that, honored Father.”

“Who first suggested this?”

“I think Great-grandmother might have offered. When they were at the party.”

His father had no expression at all for several heartbeats. Then he lifted an eyebrow and said, “Women.”

“Shall I ask mani, honored Father?”

“Oh, do. Better mygrandmother than heruncle.” His father kept looking at him, or through him. He stood still. It was never a good idea to interrupt his father’s thinking.

“It is not,” his father said, “a bad idea. —And you did not suggest it.”

“No, honored Father.”

His father waved a dismissal. “Go. Send a message to your great-grandmother. You are not to leave the apartment until she sends for you. She is occupied with the legislation. But she will read your letter.”

He had not at all expected to be able to go in person. They were still under the security alert, about Grandfather. “Yes,” he said, bowed again, went out to the hall and took his aishid back to his own sitting room.

“What happened?” Jegari asked.

I think my mother is sniping at my father,was what he thought. She knew his father did notwant Great-grandmother entangled in his affairs. He had fought that all his life.