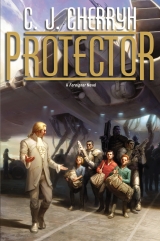

Текст книги "Protector "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

The servants nodded a polite respect, and rolled the cage right through the door, into a suite with big, wonderful, sunny windows, tall as a man, and filmy white draperies that blew in the breeze from the open windows. It was a beautiful room. Nippy from the breeze, but after all the traveling, even that felt good.

“Put him near the window, nadiin,” Cajeiri told the servants. Nand’ Bren’s servants had wired the cage door shut for the trip, and there was no way Boji could get loose. He was bouncing from one perch to another and looking very undone, panting, once the cage stopped, and staring at him with pitiful white-rimmed eyes, with his fur all messy.

“Poor Boji,” he said, putting his fingers through the grillwork, so Boji could smell them and be sure it was him. “Poor Boji. I am sorry, I am sorry. —Close the window, Eisi-ji. They have spilled all his water.” It was in a glass jar with a tube, and it had emptied with the bouncing about. He was sureEisi and Lieidi had kept him watered and fed on the train. “Get him water. And an egg. Poor Boji.” Boji was crowding close to the grillwork, up against his hand. Boji put his longest finger out and clamped it on his finger. It was very sad.

“Is he all right?” Artur asked.

“Just scared.” He kept his hand where it was. Artur reached out, but Boji moved away.

“He’s a monkey,”Irene said. “Just like in the archive.”

“Sort of. He’s a parid’ja. They eat eggs. They climb after eggs, for people.”

“Climbafter eggs.”

“Some. Two kinds.” He could not remember the word for dig. The baggage was starting to arrive, and with it, there would be eggs. He kept soothing Boji, and Lieidi came back with the water bottle filled and put that in place. Then Eisi found the right bag and came back with an egg.

“There is one egg left, nandi. He has had five, on the trip.”

Five. They had stuffed him. He looked exhausted and mussed, but his little belly looked round. “Well, he may have one more. Arrange for eggs, Eisi-nadi. But, Eisi-nadi, Lieidi-nadi, these are my guests I have told you about. This is Irene-nadi, Artur-nadi, and Gene-nadi.”

“Hi,” Eisi said.

“Hi!” Gene said back, looking surprised.

Cajeiri grinned. “My aishid knows more words.” Antaro and Jegari were back in the bedroom, arranging things, and he thought Veijico and Lucasi had gone out a moment ago—possibly to check in with house security. That was what they were supposed to do. “They have a few words.” He nodded, so that Eisi and Lieidi could get to work. “You hold the egg, Gene.”

He handed the egg to Gene, then unwound the wire so he could open the door.

But the moment the door was open, Boji launched himself at him, chittering, and held on—which was going to ruin his collar lace. He calmly reached for the egg Gene was holding and held it up so Boji could see it.

Boji just reached out one arm and took it.

“You do not eat that and hold on to me,” he said, and moved his arm to make Boji shift toward the cage. “Go on. Go back in your cage. You can take your egg. Good Boji.”

“Does he understand?” Irene asked.

“He understands a little. He has had five eggs already. He is not that hungry. But he always wants an egg. There.” He was able to transfer Boji to a perch, with his egg, and to shut and latch the door. He brushed off his sleeves and front. “He loses fur when he is scared.”

“Look at him!” Artur said. Boji had opened his egg his way, tapping it with his longest finger until he could make a little hole, then widening that hole until he could use his tongue.

“Amazing!” Gene said.

The egg was empty, very quickly, and Boji, much relieved, began grooming himself, very energetically. His guests were fascinated, watching every move, but staying far enough away not to scare him. Soon Boji, very tired from all the excitement, fell asleep, and theyfell to exploring the sitting room, and the bedroom. He showed them the bath and the accommodation, too, which were down the hall.

When they came back to the room Boji woke up and set up a moderate racket, rattling the cage and wanting out. Cajeiri went over to quiet him.

“Can we take him out of the cage?”

“Very excited. He climbs. Not a good idea.”

“There’s a house down there,” Gene said. He had looked out the window, moving aside the filmy curtains. “Lots of rails. Look! There’s one of the mecheiti.”

He already had an idea what couldbe there, and he immediately came and looked out. Uncle’s stables had been set on fire last year, in the fighting. And it was all rebuilt as if nothing had ever happened. That was a wonderful thing to see. “Those are Great-uncle’s stables,” he said in Ragi. And in ship-speak: “Mecheiti live there. If mani lets us, we can go there.” Back to Ragi. “Maybe they will let us ride.” And ship-speak: “Go on the mecheiti.”

There were apprehensive looks. He had told them about riding up on the ship. They had thought it would be a fine thing. Now—

“They’re awfully big,” Artur said.

“I can show you. Even mani and Uncle may go. We can go all around inside the hedges. If they let us.”

They were far from confident about that.

“What do you do if they don’t want to do what you want?” Artur asked.

“Quirt,” he said, and slapped his leg. “Doesn’t hurt. They just listen.”

They all looked, for some reason, at Boji.

“We try,” Gene said then, in Ragi. “We do.”

“We try,” Artur said, not quite so confidently.

“We try,” Irene said last. Irene was scared of a lot of things. She was never sure she could do things. Irene had always said her mother would not let her do this, and her mother would not let her do that. Whatever it was, her mother would not let her do it. Cajeiri remembered that, and he found he understood Irene, now, a lot more than before.

“Well, you will not fall off,” he said. He became determined that Irene would get a chance to do lotsof things her mother would neverapprove.

• • •

Shedding the bulletproof vest had been first on the list. Changing to a simple coat and dropping into a plump chair was second, and having Jase across from him in a quiet chance to rest and talk was something they hadn’t enjoyed in a year.

Banichi and Jago, Tano and Algini all settled down to a quiet, comfortable rest right with them, standing on no ceremony. They’d all lived together. Polano and Kaplan, who didn’t speak Ragi and weren’t entirely informed of the political intricacies, had gladly opted for baths down the hall, and a quiet rest next door, in Jase’s suite.

Supani and Koharu kept the water hot and the teapot full—there had been a very nice service waiting on the buffet. They were on duty for the first time during the trip, while Banichi and the rest had seen nothing butduty since well before dawn.

“I’m doing pretty well,” Jase said, momentary lapse into ship-speak, when he asked. “My spine’s almost quit popping, and if I can shake this headache before dinner, I’ll be great.”

Bren understood that. His own last shuttle flight had been as fast as they could make it, a hard burn from the station, to a fast dive and a landing on Mospheira. Jase’s flight this time had been far more conservative. “You certainly were a surprise. To allof us. And that’sunusual.”

Jase had said the captains had sent him. And that it was for the captains’ reasons—flatly that they were using the children’s visit. And hadn’t cleared it with Tabini orthe dowager.

Assessing the situation on the mainland. He could well understand that.

“I have a little guess,” he said, “that the situation between the Reunioners and the Mospheirans on the station is making life difficult for the ship-folk You’re outnumbered, even if you have all the power. I heard a little of this from Geigi. You and the Mospheirans and the atevi as a bloc can outvote the Reunioners on every issue. But now you’ve got them straining to break awayfrom this station and establish a new colony out at Maudit.”

Jase nodded slowly. “That’s pretty accurate. It sounded good at first. Less so, considering the tone the Mospheirans have provoked out of the Reunioners. At first it seemed as if the Mospheirans hold the Reunioners personally responsible for the sins of their ancestors. But when the Reunioner leaders started calling the Mospheirans traitors—you’d believe the Mospheirans were right.”

“Is Braddock at the head of this?”

Louis Baynes Braddock. That was the Reunioner stationmaster—who’d resisted all reason when it came time to abandon Reunion.

Hadn’t liked relinquishing his power, not at all.

“Definitely. We could prosecute him for the things he did at Reunion. But with us voting with the Mospheirans on every issue, that action doesn’t look disinterested. There’s a lot of heated rhetoric. Now that the Reunioners are starting to splinter on the Maudit issue—and there isat least some balking on Braddock’s plan—these kids, with a peaceful, personal connection to the aiji’s son—they offer something you can’t turn into a political ploy. The contact makes the Mospheirans just a little nervous. They think, I guess, that the kids’ relationship will give the Reunioners some sort of special access. But they’re onlythree kids—and the Mospheirans have youfor reassurance. That’s why I said it’s for ourreasons, my being here. Braddock doesn’t want this mission to succeed. The moderates among the Reunioners, who have no clear leader, do. The atevi are calm about it all. The Mospheirans have had one anonymous wit say these three kids already show better sense than Braddock. That’s caught on—and Braddock isn’t happy. Weare. Lord Geigi and the moderate Reunioners are watching this, not knowing quite what to hope—but hoping, all the same, that if there wereReunioner paidhiin—the Reunioners don’t remotely understand that word, really—that their influence might win out, not just in a decade or so—but now—over Braddock’s.”

“Did they explain the paidhiin tend to be shot at?”

“I don’t think they mentioned that part.”

His aishid found quiet amusement in that. He noted it. Probably Jase did. Jase had a sip of tea and said, in Ragi, and with a nod: “I told Lord Geigi. He said he thought it was the best decision. Then he added something else. That some Reunioners may thinkthey can set up a colony and run it their way. But that, in the spirit of the agreement between humans and Tabini-aiji, if we should go out to Maudit—Mospheirans, Reunioners, and atevi should have a share of it.”

“You know,” Bren said, “Tabini would surely appoint a lordship to oversee an atevi establishment there, if it were seriously proposed. But what Tabini morefavors is the promised starship. The coup delayed it. He wants it. I’m sure he raised that point with Geigi. Thereis Reunioner employment.”

“Braddock is not in favor.”

“Poor man. He will not get all he wants.”

Jase said seriously, “The Reunioners have only just become aware that the world doescontrol the resources. All along they’ve made up reasons for why atevi came with us to Reunion. They have no understanding of just how important Tabini-aiji is to this world in general and their rescue in particular. They missedthe last two hundred years of Mospheirans and atevi making this arrangement work, they missedTabini-aiji pushing for greater tech and for making the whole space program possible. And now they have Braddock telling them everything wetell them is a self-serving lie.”

“Ignoring the fact, as Braddock always has, that we could have alien visitors dropping by any day to seeif we lied to them,” Bren said. “The man’s a fool. The last thing we need is to have him in charge of anything, let alone an entire station. He nearly got them killed once already. Have they forgotten?”

Jase shook his head. “Never underestimate the power of people to be swayed by what they want to hear. But three children, three of their own, in complete innocence, are saying something that contradicts Braddock—and no few Reunioners are following this, closely, and for the first time listening to actual information. So, yes, the Council put pressure on the parents—promised the kids would be safe. Promised—well, at least suggested it could be advantageous. A guaranteed future for the kids.”

“One is glad to hear that,” he said. He declined to let Koharu make another pot. “We daren’t have another round. We’ll have formal dinner coming up. No question.”

Algini got to his feet quietly, and Tano followed suit, the both of them excusing themselves with a little bow. It was nothing unusual.

It was a little more unusual that those two put on their sidearms and left, but security responded to a lot of signals that were simply precaution, and they equipped under whatever rules were current. They might have gotten a call about something as routine as a query from the kitchen.

Banichi and Jago, however, at apparent ease, stayed until the pot was empty, and when Jase declared he had to dress for dinner, Banichi got up and saw Jase to his room.

Jago said then, quietly, “There is, Bren-ji, still information on Ajuri movement. They are nearer, but not trending in our direction.”

“Is there any interpretation?”

“It is eastward movement. This takes them more toward the road home.”

“Giving up, do you think?”

“One is not certain, Bren-ji. Possibly. Or possibly not, if they decided to enter Purani territory and keep a township between us.”

Those lesser clans with ties on both sides of the question—clans which typically tried to stay out of difficulties between their larger neighbors.

“We are keeping an eye on the matter,” Jago said, “and we will use Taibeni Guild to advise Ajuri Guild that they are treading delicate ground. If they do not know we are here, we are not informing them.”

Not sending things through Guild headquarters. He understood that.

“More of it later,” Jago said. “We shall see if they regard that, or if Komaji is bent on making a nuisance of himself.”

Komaji. Damn the man.

“How is our situation?”

“We are satisfied,” Jago said in a low voice. “We have removed certain suspect servants. We have confidence in Lord Tatiseigi’s remaining staff, we have laid down strict rules about outside communication, and we have moved in our elements not only under canvas, out by the gates, but in positions within the house. We have set up our own equipment, that we know is clean. Lord Tatiseigi’s house sits isolated within its hedges—a virtue. We control the grounds so that nothing can move unnoticed. If Ajuri comes no closer, we should be able to let the children go out and about, ride as they please, if they please, explore the immediate area of the house, and enjoy their holiday. Tabini-aiji is safe and Geigi is in the heavens. The young gentleman and his guests are under our eye and with a great deal of secure space about them.”

“Despite the Kadagidi?” he asked, regarding Tatiseigi’s neighbors to the east.

“We are watching them,” Jago said. “We are advised that Geigiis watching. He has that ability. Not even a market truck has moved around the Kadagidi estate. They are being very quiet. There have been no arrivals or departures. We have temporarily detained everyonewho has been removed from Lord Tatiseigi’s estate, we swept the area of the train station, so there were no observers there. They likely know about the Taibeni making an agreement with the Atageini. They will not be happy with that. And they may be aware that Taibeni are here and about the train station—they will be wondering what that is about. They should be alarmed by the sudden silence from their spies, and they may well be conferring over there, asking themselves whether Tabini-aiji has taken a more threatening stance against them, whether the Taibeni, closely related to him, are part of this plan—but being barred from court, and forbidden to come into Shejidan, they will have to get their information from the news and from their spies in otherplaces. This area has gone dark to them. They are very probably looking to their defense and trying to get information. If that effort occupies them for a number of days, that will be enough to let the children have their holiday and go on to Shejidan. After that, we will let our detainees go, with compensation, which we shall arrange, they will be free to reveal that they have been dismissed from their posts at Tirnamardi—we have no wish to compromise their safety. But since they have worked for the Kadagidi—let the Kadagidi support them hereafter. At that point, at least, if they have not been alarmed before, the Kadagidi will realize they are dealing with a stronger and evidently permanent establishment on their border. That will not shift their man’chi in the least—but it will have warned them that Lord Tatiseigi no longer needs turn a blind eye to their trespasses.”

For much of the last century, the Kadagidi had viewed themselves as the most powerful clan in the Padi Valley, and the Atageini as not quite their ally, but as under elderly leadership, clinging to the old ways, too independent to be ruled, too important to assassinate, and too lost in his own world to threaten anyone.

It wasgoing to be an unhappy realization for the Kadagidi. Tatiseigi was several of those things, but lost in his own world, incapable of playing the political game?

No. Not quite.

• • •

Dinner needed almost-best clothes. Eisi and Lieidi had unpacked everyone, there were baths down the hall, and Eisi and Lieidi had steamed all the wrinkles out and helped them dress, except Irene, who, in her too-large bathrobe, disappeared into the closet to dress. They had no queues nor ribbons to fuss with—their hair was short. Their day clothing was all ship-style, very plain, blue suits, or green or brown—But Geigi had seen they each came with two good dinner coats, and shirts and trousers, proper enough to be respectful of a formal dinner. Nobody had even thought of it, but Geigi had, and the sizes were all perfect.

His guests were excited and a little embarrassed at clothing they had never worn. There was a little laughter, and the short hair was very conspicuous, but then Artur’s red hair was conspicuous on its own. They turned and admired one another, excited and nervous about it all. True, they were not quite in the latest mode, but Geigi had dodged any conflict of house colors, had everything absolutely not controversial, all beiges and browns and a shade of green and one of blue that just was not in any house. There was lace enough, and Gene said he was afraid he would get his cuffs in his food.

It really was a trick, he realized, and he had known it forever: he showed Gene the knack of turning his hand to make the lace wind up a little on his wrist, and the rest copied it.

They were very pleased with themselves. And they laughed.

But just then a little rumble sounded in the distance, a boom of thunder—and they all froze and looked toward the east.

“Thunder,” he said. He had tried to tell them about weather. He remembered that. Weather was coming in, and he did hope if it rained, it would not rain a lot, and that it would clear by morning, so they would not be held indoors.

They all went to the window, to look out. But the thunder had been in the west, and the window faced east.

It was getting dark, on toward twilight.

“Come,” he said in Ragi. “Come. There is a window. Likely we can see it.”

He led the way out to the hall, where, at the end, there was one big window, and he led them to the foot of it, by the servants’ stairs—and indeed, they could see the clouds coming in, a dark line on the horizon to the left. Lightning flashed in that distant gray mass, and after a moment, thunder sounded. “It is quite far,” he said. “It will be here by full dark.”

“Is there any danger?” Irene asked.

“Being outdoors, yes. If it strikes down to earth, it goes to the tallest things.”

“The house?”

“The house has protections,” he said.

“Those people are out there by the gate,” Gene said.

“They will have a wet night. But they will know what to do. They all will be safe. Come. We can go downstairs. I shall show you from the front door if I can persuade security.”

They went with him, excited, and Antaro talked with house security, and said they wanted just to look out the door, for the guests’ benefit.

“They agree,” Antaro said, so they all went, down all the way to the front door, and Great-uncle’s major domo opened it for them, while Great-uncle’s security stood by.

Just in that little time, the bank of cloud was closer, and the wind had begun to blow.

“Oh!” Irene said, as a gust came at them, and lightning obligingly flashed in the cloud.

“Neat!” Artur said.

“This is so good,” Gene said, and walked out onto the porch, with the wind tumbling his hair and blowing at his coat and his lace.

They all did, and the wind blew in their faces, and the thunder rumbled.

“It smells different,” Irene said.

“It smells like rain,” Cajeiri said in Ragi. “You shall hear a storm your very first night!”

“It’s different than the archive,” Irene said, and flinched as lightning went from cloud to cloud. “They don’t show us the planet.”

“Who doesn’t show you the planet?” Cajeiri asked.

“We’re Reunioners,” Artur said. “We don’t get the same news as the Mospheirans. As the atevi, too, likely.”

“Why not?” Cajeiri asked, while the wind blew at them, and the guards behind them.

“It’s not our planet,” Irene said then. “We’re not supposed to know things.”

He heard it. He thought about it a moment. It was not right. It could not be right.

“I never heard that,” he said. “Who said that, nadiin-ji?”

“We don’t know,” Irene said. “But we know Mospheirans get their news. We don’t.”

He had to askabout that. He had to ask nand’ Bren, and nand’ Jase why that was. And he had to ask mani if she knew about that.

“Well, now you have seen a thunderstorm,” he said. “And we should go in and let the major domo close the door.” He led them back inside. The door shut, and he debated between the utilitarian lower hall, where there were interesting things, and the gilt upstairs. “I shall show you the main floor. You saw the upstairs foyer. But I shall show you the breakfast room, and the sitting room.”

“New words,” Artur said. “Irene, get out your notebook.”

“I have it,” Irene said, patting her pocket. And said it again in Ragi. “One has it, nadiin-ji.”

“You have to say,” Cajeiri said reluctantly, “ nand’Cajeiri, nadiin-ji, when you are in my uncle’s hearing. And mani’s.”

There was a sudden silence. A little hush, and he was embarrassed.

“It is the world,” he said. And in ship-speak: “It’s the world.”

“No,” Gene said, “Captain Jase told us. He explained. Nand’Cajeiri. We can’t forget that. And your great-grandmother is nand’ dowagerand Lord Tatiseigi is nandi.And we bow.”

“Nadiin-ji.” He gave a little bow of his own, conscious that, just a year ago, he had been no taller, and they had shared things, and there were no guns and guards all about them. It wasdifferent. It was very different. He would never again be just nadi-jidown here, or up there.

They had tried more than once, last year, to work out those forbidden words—man’chi, from his side, and friend, from theirs. Love. Like. All those things he was never supposed to say to them, and they were never supposed to say to atevi—well, they were never supposed to talkto atevi, which was why they had met in the tunnels, but they had found a way to talk, and they hadtalked, and they had an association they all believed was real.

And they were back to that, with his aishid standing next to him, and with Great-uncle’s guards nearby, and him having to remind them—that if they were going to continue as associates, on the world or in the heavens—he would have to be obeyed.

“Nandi,” Artur said. And Irene said, after thinking about it, and with particular emphasis and a polite little dip of the head: “Nandi.”

Thunder boomed, outside. There was silence after that. They were waiting, looking at him. Hegave the orders.

“We shall go upstairs,” he said, not sure their offering was man’chi, with no way to tell if it was friendship, no way to tell what they were trying to be, or whether he was pushing them away—but they tried. “Nadiin-ji, I shall show you the main floor, the parts you missed, and then we should be in the dining room before mani and Great-uncle.”

• • •

They werefirst into the dining hall, waiting with a little light fruit juice, when Bren came in, and Jase, with just Banichi and Jago.

“Well!” nand’ Bren said in ship-speak. “Nand’ Cajeiri, nadiin. A very nice appearance.”

“One is gratified, nandi,” Cajeiri said, for his guests, who copied what he said, a faint echo.

Jase asked, “How do you like the weather? They have arranged a storm for us.”

“Nandi.” They all said it, and nodded in just the right degree. “Interesting, nand’ paidhi,” Gene said, very properly. “We went down and looked . . .” He ended with something quite unintelligible. Artur choked and looked away, trying Cajeiri could tell, not to laugh, which would be rude. But Irene clarified for Gene: “Looked out from the door, nandi.”

“Security approved,” Cajeiri provided quickly.

“One indeed heard so, young gentleman,” Bren said.

By the tapping sound echoing in the high hall outside it was clear now Great-grandmother was coming, and Great-uncle, and the bodyguards took their places, standing by, as mani’s and Great-uncle’s bodyguards arrived, and went to their places at opposite ends of the table. They all stood up as mani and Great-uncle came in, and servants positioned themselves to help with the seating.

“Well,” mani said at the sight of them. “Such a splendidly turned out company.”

“Nandiin,” Gene and Artur mumbled. “Nand’ dowager, nandi,” Irene said, the proper form, very faintly, at the same time. They all bowed, they all sat, and to Cajeiri’s relief mani and Great-uncle seemed extraordinarily pleased, though they went on to talk to nand’ Bren and nand’ Jase while the servants poured wine and water. Then they talked about the shipment of part of Great-uncle’s collection to the museum in the Bujavid.

The first course arrived. And adult talk went on, talk about the neighbors, while Cajeiri said nothing at all, not wanting to draw his guests into thatdiscussion. His guests were all quiet, very quiet.

The second course, and Great-uncle asked if the guests had noticed the storm rattling about outside.

“Yes, nandi,” came a chorus of whispered answers, everybody sitting upright, eating some of everything they were offered, though once or twice with a shudder. They were being exemplary, Cajeiri thought. Hecould not eat the pâté.

The third and fourth and fifth courses came, with occasionally a question to the guests, and a little adult talk. They all kept to Yes, soup, please and not a word in excess, except that they were delighted by the fruit and cake dessert, and ate all of it.

Then Great-uncle put aside his fork and said that they might attend the brandy hour.

Cajeiri had rather planned on an escape. But he bowed and said, carefully, as everyone was getting up, “You are greatly honored, nadiin. We are offered tea with mani and Great-uncle.”

They were brave. There was not a sigh, not a frown in the lot. They just got up and went to the sitting room.

And just inside the door, before they had a chance to sit down, Great-uncle stopped, and signaled his head of security, who handed him a folded paper. “Nephew,” Great-uncle said, and handed it to him. “One delights, on the approaching felicitous occasion, to present you with a gift, from your great-grandmother and myself.”

Cajeiri looked at the paper, and found a name: Jeichido, daughter of the second Babsidi and Saidaro.

He knew Babsidi. Babsidi was mani’s mecheita, leader of mani’s herd.

“The dam was mine,” Great-uncle said. “She is not a leader in my herd—you are, after all, a young rider—but she will not shame you. She is yours.”

“Great-uncle!” he exclaimed.

“An earnest, Great-grandson,” Great-grandmother said, “of the stable you will one day have, and a son of the first Babsidi will be yours when you have the strength and the seat.”

“Shall we ride, then? Is she here?”

“We shall ride,” mani said firmly. “We have the grounds under our control, we expect this storm to pass and leave us clear skies, and it has been far too long, fartoo long. If your guests will wish to ride, your great-uncle has several fat and retired mecheiti, who will go very gently.”

“Yes!” he said, and bowed deeply, to mani and to Great-uncle.

“You must remember that you have guests, and not run. We shall not be other than sedate, Great-grandson.”

“No, mani. We shall not. Thank you!” He was happy, happy beyond all his expectations. Nand’ Bren and nand’ Jase looked uneasy. But mani said it was safe, and Cenedi, right next to mani, looked perfectly content. “I shall tell my guests. Thank you!”

He took the precious paper, which, once he got back to the Bujavid, was going to go into that little box, not in his office, but in his bedroom, where he kept his most precious things . . . not that anyone would ever dispute mani’s and Great-uncle’s gift—but that was a box full of things that made him feel good, whenever he was disheartened. He showed the paper now to his guests, and opened it, with the date of Jeichido’s birth—she was ten—and the names of all her ancestors.

“Mani and Great-uncle have given me a mecheita of my own, nadiin-ji. And we shall ride tomorrow. On mecheiti. We shall go on mecheiti.”

“We,” Artur said. “On mecheiti.”

“Mani promises we shall not run. We shall be very safe. They will not go fast.”

“How do you tell them that?” Artur asked, in ship-speak this time. “They’re taller than the bus!”

“Not as tall as the bus,” Cajeiri said, which was the truth. They only came up to the windows. He was disappointed, but he whispered back, “If you’re scared—”

“No,” Gene said in Ragi. “I shall go.”

Artur looked doubtful, but he nodded.

That left Irene, who looked scared to death. She clenched her jaw and said, very faintly, “Yes.”

• • •

“Shall we be safe out there tomorrow?” Bren asked, once he and Banichi and Jago got back to their quarters, two brandies on, and got a very, very slight hesitation.

“We have some concern,” Banichi said. “But in this gift and this event, Cenedi says the dowager is particularly determined. She had planned this for after the party, in the Bujavid, and with no access to Lord Tatiseigi’s stables. But the opportunity is here, and given the attractions of the visitors, and the unhappy situation in the Bujavid, which may or may not be resolved by the time we return—Cenedi’s assessment: she would not be crossed in this.”