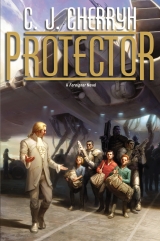

Текст книги "Protector "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

It had all come as a shock to traditional beliefs on the continent—and a shock to human perceptions of their situation as an earthly island expecting invasion from the mainland. The aftershocks were still rumbling through the world. But the agreement had worked for everyone—until the ship-humans finally decided to contact the colonists theyhad left at their former base of operations, at Reunion Station, light years removed from Alpha Station and the world of the atevi.

Another species had taken exception to the human presence in that remote location. Removal of that colony had become a necessity.

And collecting every human from Reunion Station and transporting them here had brought a fourth population onto the space station, five thousand technologically sophisticated humans they’d naively assumed were going to fit right in.

But the Reunion-humans had run their last station as they liked and thought they should run this one. In point of fact, their ancestors had governed the first space station, and were the very ones the Mospheiran humans had fled the station to escape.

Mospheirans, ship-humans, and atevi all united in objection to the Reunioners’ assumption they were the incoming elite. Together, the three populations outvoted the Reunioners—who were not happy, not in meeting the Mospheirans’ ancestral antagonism toward them, not in the ship-humans, who voted withthe Mospheirans, most of all not in the number of non-humans in residence and in authority. Expansion of the station to accommodate the larger population would have been logical—but they were not, politically, happy, and they could not agree on how many hours should constitute a day, let alone how the station resources and manpower should be directed.

To mediate the problem, the Mospheirans had suggested resurrecting the Maudit Project, first proposed centuries ago, when the ship had arrived at a too-attractive, inhabited planet and the ship-folk had begun to lose control of the colonists, who wanted to land. The ship-captains of that day had wanted to pull their whole operation off to the next planet out from the local sun, where planet-dwelling was not so attractive a lure, where there would be no talk of colonists abandoning the station and landing on the planet, outside the authority of the captains and the crew.

Park Phoenixat Maudit, they’d said in those days. Build a station, mine the asteroids and moons which were not so far distant from Maudit—and stay entirely space-based, above an uninhabited planet nobody in their right minds would want to choose as a residence.

Their colonist population had wanted none of it. They’d deserted the station in droves as relations between the station administration and colonists deteriorated—the colonists absolutely dead set againstpulling off to Maudit, the ship’s captains and crew dead set on doing it. So they’d finally drawn Phoenixoff with a complement of high administration and willing colonists—with the stated objective of finding a better world at another star.

In point of fact, they’d seen no chance of winning under current circumstances, and had set out, in the typical Long View of their spacefaring kind, to win the argument and give their ship the base they wanted by producing a new batch of colonists who’d support their ship at another base, far away, at a planeted system—so they said. Their real objective had been to get far from the temptation of the atevi world and build a civilization in space.

Now, centuries later, back on the original station, with the rescued Reunioners, the ship-captains had a problem. They’d not anticipated the antagonism between colonists. Neither Mospheira nor Tabini would let them land the Reunioners and be rid of them thatway—

So, during the last eventful year, the captains had fallen in with the Maudit plan again—give the Reunioners a whole station of their own at Maudit. And gain all the mineral resources Maudit offered. Gain the wider spread of human population. It was a quiet suggestion. It had taken off on the wings of Mospheiran agreement.

The Reunioners, Geigi had reported, had also leapt on that idea. It seemed to be win-win. The Mospheirans were for it . . . as the fastest way to see the last of most of the Reunioners.

There was just that troublesome issue of who was going to be in charge of the Maudit colony. Depend on it– thatquestion had immediately surfaced. There was no getting away from the fact that the Reunioners expected to be in charge of whatever they built new; and the Mospheirans were bent on seeing they were in charge of nothing.

True, Cajeiri’s young associates were Reunioner children—but one might have assumed the childrenwere innocent of plots.

“So,” Geigi said eventually, on his one sip of the brandy and a long pause for thought. “You have had as much experience of the Reunion-humans as I have. And with far more understanding. One has not wanted to poison the situation by bringing politics into the matter. But—”

“The Reunion humans are a difficult lot,” Bren said. “I was on the ship with them.”

And Tabini hadn’t been. The whole Mospheiran-Reunion question was a human question. Tabini, at the moment, was not taking on additional problems. Tabini had come back from two years of hiding and dodging assassination attempts and had a great deal on his mind that didn’t at any point involve understanding the Reunioners.

His son, with whom he had a difficult relationship, wantedthe Reunioner children for a two-week visit. Cajeiri had been promised it—last year. Cajeiri had looked forward to it, clinging to his ship-speak and his memory of the only children he had ever played with in his adult-surrounded life.

No, Tabini had had no expectation the childrenwere going to cause a problem, since the paidhi-aiji hadn’t been convinced there was a problem. Tabini wanted to keep a promise to his son and win his son back—the same as Damiri wanted, only more so. Cajeiriwas Tabini’s heir. Next in line to be aiji.

And on that boy’s man’chi, his sense of loyalty to his father and his kind, the future of the world depended.

“What problem do you see in this visit happening, Geigi-ji? Inform me. And you need not be politic at this hour. Have I been wrong?”

That Tabini didn’t understand was possibly his fault. But it might be one of those damnable instances of intercultural reticence. Which is worse—to have the boy renew acquaintances with children of a troublesome population—or to have him always wantingit, into his adult life?

“There are nuances of behavior in this which trouble me,” Geigi said, “the more since I began to help this contact along. The parents at first strongly opposed this association, and that seemed natural, given the general mistrust of the Reunion-humans toward us and the slow poisoning of the relationships on the station. I had met with the captains some time ago, to try to explain the situation on earth, but then one parent began to ask why the children’s letters went unanswered, and the captains andthe children’s parents seemed to lean in favor of a meeting. This led me to bring the letters down. This is where one belatedly asks human advice.”

“Tell me what you observe.”

“This. You know about the Maudit issue.”

“Yes.”

“The Reunion humans have, for most of the year, been unanimous in favor of going to Maudit. Now they have developed a splinter group that opposes the idea—the ship-aijiin believe them to be a labor group that has fallen out with Reunion leaders. This group, about five hundred of the five thousand, want to become citizens of the station here, assuming the Maudit expedition does eventually launch. They claim they will sustain themselves in the trades. This does not please us, of course, since we have our own industry, and a niche for them limits us. The ship-aijiin, for their part, do not trust their political motives and do not trust the faction that wants to leave, either. Mospheiran humans are asking atevi to join them in a call for a referendum on allowing any Reunioners to remain on the station, and to vote againstthe Reunion humans being allowed to stay. This was going on when I left.”

Thatwas a nasty chain of developments. But—

“Do you think the children’s parents are trying to avoid being sent out to Maudit? That they hope a connection of this sort could prevent their being removed?”

“There is, as always, the subtext,” Geigi said. “Remember, Bren-ji, half a year ago, there had attempted to be a vote about the use of Phoenixas a transport for Maudit, to get the operation underway immediately. The Mospheiran humans wanted it—they wanted to be rid of the Reunion humans as soon as possible. We were with them at the start. But the ship-humans denied that any station vote could bind their ship to do anything at all. A station vote would challenge their authority, on a matter of principle and their law. We then abstained from that vote, as an uncivilized suggestion, if the ship-aijiin were standing on privilege of their territory. The vote, you recall, failed.”

A very small sip of brandy. Geigi had talked a great deal tonight. His voice grew hoarse.

“And that meant the Maudit venture was foreseeably delayed. Then came the counter-proposal: to have shuttlecraft built specifically for Maudit, largely robotized, to deliver cargo and colonists in stages and continue to serve as freighters, followed by the usual infighting: the Mospheiran humans demand Mospheiran piloted craft all under the control of the Alpha station; the Reunion humans want piloted craft controlled by Reunion humans, based at Maudit. The ship-humans are now standing with the Mospheiran humans and have abandoned the robotic option. I have tended to the idea we should vote with the ship-humans and the Mospheirans. But now I think this whole Maudit matter should be reconsidered. These two populations hate each other. I am beginning to think it will lead to trouble nobody will benefit from.”

He had heard about the business. Mospheiran news had reported it. He had had his reports from Geigi. In the Mospheiran press, the Maudit colony had begun to look very much like a dead issue. He had brought it up with Geigi. But when they had talked about it, it had not been in the context of the children’s visit, and something had interrupted the conversation: he could not recall what, at the moment—the assassination attempt in Sarini Province had jarred his attention sharply elsewhere.

“One strongly agrees,” Bren said. “Neither side will keep agreements, Geigi-ji, so long as one group thinks they should rule the other. Maudit will not settle it. It would make it worse.”

“The crisis will come on the station, then,” Geigi said, “and one dislikes to see it. Station-humans are politicking very hard with the ship-humans, to secure a lasting association between them, being space-born humans. I can use their words, but what I am asking, Bren-ji, is whether my interpretation is accurate. We andthe Mospheirans can out-vote the Reunion-humans. But one asks—will Mospheira then break from us at some future date? Are we placing ourselves in the midst of a human quarrel in which human loyalty will dictate some turn we do not foresee?”

There was nothing Bren could say, no reassurance he could give, and Geigi nodded. “It is some human signal I have missed, then.”

“It is not.”

“Which brings us to this business of the children.”

“How so, Geigi-ji?”

“The Reunion-humans who do not want to go to Maudit, the ones who want to stay, use this word assimilation.”

“To become in-clan,” Bren said. “To become one with the Mospheirans. This is what we initially hoped would happen. But the way politics has so readily sprung up, no, not so easily. This is a power struggle. These people have seen a very frightening situation out in space, alone. Fear of being abandoned. Fear and distrust of their leaders—remember that their leaders takepower by having a coalition of supporters. Distrust of the leaders is very possible. There will be a rival set of leaders attempting to gain followers. They will turn to the ship-humans, once they see the Mospheirans will not give them positions of authority. Maudit is an issue—but one they will politicize and argue for years. I suspect the Maudit issue is already dead, though some will not admit it. And as I see it, Mospheirans and ship-humans would be very wise to stay united with atevi.”

“This insanity equals Marid politics.”

“It is not that different. Except that among these humans there are no clans. There will be a committee in charge, and you will see a great deal more milling about than atevi will do. Let me guess now. The children’s parents are in this number who want assimilation.”

“Yes. Precisely. Three of them seem not so enthusiastic about their children being guests here, and one of those three, oldest of the boys, named Bjorn, aged thirteen, is now in an advanced training program—he is very bright, and has real prospects. His mother is very reluctant to see him give that up, since he might risk dismissal, should he accept the young gentleman’s invitation. The questions of the parents of the other two boys were reportedly about safety and supervision, which seems a natural thing. In the case of the girl Irene, however—I have this from the ship-humans—her mother has been fearful and suspicious of atevi. She was embarrassed by Irene’s meetings with the young gentleman on the ship, and was strongly against any association. I have been warned of this. Yet at a certain point she personally brought a set of letters which she said shehad withheld, and was very polite, if highly nervous. One is suspicious that these letters are of recent composition. They lack the historical references of the others. And yes, we have read them.”

“One would not fault that at all, Geigi-ji.”

“There are indications, my sources say, that this woman has been approached by others of exactly the sort you forewarn . . . but it would not be a turn of man’chi driving this change of mind, would it? What, then, can so profoundly change this mother’s opinion? She is a woman without administrative skills. She has been public in her detestation of atevi. Now she approaches my office bowing after our fashion and begging to have her daughter go.”

“She is not likely leading anything,” Bren said bluntly. “But may have someone urging her to be part of this. One cannot fault your observation in the least, Geigi-ji. The three reluctant ones ask proper questions. Irene-nadi’s mother believes her child will be in the hands of those she hates. Yet what she can gain from sending her must matter more. That is my opinion.”

Geigi drew in a breath. “All this came up just as I was leaving and trying to gather information on the situation on the coast. I brought the letters. I have apprehensions I attempted to convey to the aiji. But I am feeling I am caught between whatever these Reunioners are up to and my aiji’s determination to keep a promise to his son. I attempted to explain the situation to Tabini. He asked me only if I saw any danger to the young gentleman at the hands of any of these children, and I pointed out that they might attempt to gain favors and influence. He said that that goes on daily and that is fully within the young gentleman’s understanding. I argued the situation further tonight, attempting to explain that these are not Mospheiran children, and that their parents may attempt to use the connection to political advantage. He said I should discuss the matter with you, and that we should take measures, but that he cannot now go back on his promise. Excuses can still be found to stop this meeting or at least delay it until some of these issues are settled. I can prevent their coming. I shall take it on my head, if necessary.”

“It would greatly distress the young gentleman,” Bren said, “and I have every confidence our young gentleman himself is no fool where it comes to people trying to get their way. If one of his associates presses him too far, I have every confidence they will rapidly meet his great-grandmother’s teaching face to face. The changes in him and the changes in them in the last year will, I think, more confuse the human children than they will him. I have thought about this. I am most concerned that there have beenno other children in his vicinity—unless one counts two of his bodyguards—and he has never forgotten what he considers the happiest time in his life. If we attempt to stop him meeting with them—we create a frustrated desire that may have the worst result, particularlyif these children develop political notions.”

Geigi nodded. “So. In the aiji’s view, he expects the meeting will go badly and that disappointment will cure all desire in the young gentleman. But in my view, Irene-nadi’s disappointment will not blunt the ambitions of Irene-nadi’s mother.”

“One other thing could happen, Geigi-ji. One or more of these children mightbecome a useful ally for the young gentleman, in his own day.”

“One would wish that,” Geigi said. “For the young gentleman’s sake. Or if not—he does have you to set it in perspective.” He finished the little left in the glass and set it down. “I have grown quite happy in my human associates, Bren-ji. In a sense—one could wish the young gentleman as felicitous an acquaintance as we both have. But I do fear the opposite is more likely the case. Note—the boy Gene, too, is a rebellious sort, already acquainted with station security. But then—one could say that of the young gentleman himself. At least—whoever supervises them should be forewarned of that.”

That somewhat amused him. “We keep a watch on the young gentleman. So we shall at least give them the chance, Geigi-ji. We shall. The young gentleman will deal with it. I think his expectations actually aretempered with practicality. Remember who taught him.”

“Well, well, you greatly reassure me.” Geigi rose, and Bren did. And then Geigi did something very odd. He put out his hand and smiled. “I have learned your custom, you see.”

Bren laughed and took it, warmly, and even clapped Geigi on the arm. “You are unique, Geigi-ji. You are a most treasured associate. What would I do without you?”

“Well, we are neither of us destined for a peaceful life, Bren-ji. But we take what we can, baji-naji. I have so enjoyed your hospitality.”

“Good night, Geigi-ji. I shall miss you.”

“Good night, my host,” Geigi said, and exited the office, into the hall.

Supani was still waiting. But not waiting alone. Banichi was there, and walked with Bren and Supani, into Bren’s bedroom.

That was unusual. “Is something afoot?” he asked Banichi, quietly, while Supani took his coat.

“Important business,” Banichi said. “But not urgent, at this hour. Rest assured everything is on schedule. Security is arranged, the car is under watch tonight, and we shall have no delays in the morning.” Then he said, to Supani, “The paidhi will wear the vest tomorrow, Pani-ji. And on every outing until I say otherwise.”

“Yes,” Supani said without missing a beat.

The vest was only good sense, Bren thought. He was not surprised at that requirement, given recent history.

“Jago will be here,” Banichi said, and that Jago would arrive in his bedroom was nothing unusual: they had been lovers for years. But that Banichi said it—Banichi meant something unusual was going on.

“Yes,” he muttered. He suddenly felt the whole strain of the past several hours. He wished he had more energy, to dive fresh into whatever the Guild had done, or was doing, and he wanted desperately to know, but he was running right now on a very low ebb.

“It can wait,” Banichi said.

The hell it could. Tension that he had dismissed in his conversation with Geigi had entered the room with his bodyguard. He smelled it, he felt it in the air. Supani, a servant of whom not even his bodyguard had doubts, helped him off with his shirt, and Supani asked in a very low voice, “Will you still want the bath in the servants’ hall, nandi?”

“Yes,” he said. Geigi, his guest, a man of great girth, facing a long flight, absolutely needed the master bath. The little shower in the back passages was all he needed. He stripped down, flung on his bathrobe, and headed out, with Banichi, whose route to his bodyguards’ rooms, next to the servant quarters, lay in the same direction.

“Truly it can wait?” he asked Banichi, in the dim hallway outside the servants’ bath.

“It was an interesting meeting,” Banichi said quietly. “Not surprisingly, the matter involves Ajuri.”

God. It was very possible he’d stepped squarely into the middle of that situation, intervening with Damiri tonight.

“One hopes not to have caused a problem tonight, Nichi-ji. The dowager made a gesture of peace toward Damiri. One attempted to intervene on the side of reconciliation, for good or for ill. One has no idea of the outcome. Tabini-aiji suggested, in private, that Damiri may try to take Ajuri as lord and he would oppose it.”

“An assessment he has also given us,” Banichi said. “The consort taking Ajuri would sever her from the Atageini, even if she then makes peace with them. There are things we do not believe either the dowager or the aiji yet know, Bren-ji.”

“About Damiri?”

“About Ajuri,” Banichi said, which widened the range of possible ills by at least a factor of two, and assured he was not going to get a restful sleep tonight. “Jago will tell you. Be extremely careful where you discuss any of this.”

“Get some rest,” he said to Banichi.

“Things did not go that badly,” Banichi said to him in parting. He was sure it was for his comfort.

“One hopes not,” he said. “I have learned things from Geigi I should mention, too.”

“Your bodyguard knows,” Banichi said, and Bren blinked. Of course there was monitoring. He hadn’t expected it to go on that late, with Geigi. But it was a relief to him that they hadheard. Reconstructing it all, tired as he was, was beyond him.

“Good,” he said.

“We shall just have a cheerful trip tomorrow,” Banichi said, “and discuss the weather throughout. Leave Geigi’s briefing to Geigi’s bodyguard once they launch. None of it affects him. Have your bath, Bren-ji. And rest.”

Bath. It was a shower. He no more than scrubbed and rinsed, threw his bathrobe on, and was on his way out the door when Jago came into the servant bath, in her robe.

“Jago-ji.”

Jago folded her arms and shut the door. “We can talk,” she said. “Narani and Jeladi have been extremely careful.”

Not all Guild went in uniform. Narani, that elderly, kindly gentleman, was an example. Bindanda, the cook, was another.

And if Jago said the area was secure and Narani had kept it that way, it was secure.

“One asks,” he said. “One does not even frame a specific question, for fear of misdirecting the answer. Tell me what I need to know, Jago-ji.”

“First, dealing with any aspect of it can wait until we have seen Lord Geigi into orbit.”

“Heis not involved,” he said. He would bet his life on Geigi’s integrity. He had made that bet. Repeatedly.

“He is involved as an ally. But if we told him everything we know, we might not get him off the ground. We have briefed his aishid: they will brief him.”

“One understands.” He did. Perfectly. “And the aiji?”

Jago drew a deep breath. “By the Guild Charter, we caninform the aiji directly of whatever touches his security and the security of the aishidi’tat, and what he then chooses to tell his bodyguard is not regulated—which has been our route for this and other matters.”

Since the last Guild-chosen bodyguard had attempted to kill him, Tabini had hand-picked four young distant relatives within the Guild. He had done it over conservative objections, bitter regional objections, and very heated Guild objections; and the Guild now had constantly to maneuver around that stone in the information flow at the very highest levels. It wouldnot grant the aiji’s bodyguards a higher ranking or higher clearance until they certified higher. And that temporarily left the aiji-dowager and, ironically, the paidhi-aiji, with the highest ranking bodyguards on earth and above it . . . and the aiji guarded by young men who had to get their information from next door.

“We have several immediate problems,” Jago said, “and your need to know, Bren-ji, has also come up against Guild regulations. So we, and Cenedi and his team—we have observed several things regarding which we are routinely going to violate Guild regulations. You need to know these matters. First is something the aiji can deal with—the Ajuri feud with the Atageini. Lady Damiri’s father, Lord Komaji, is back in Ajuri, telling his version of what happened, and why he was dismissed, and why Lady Damiri’s staff was dismissed. His lies involve your influence, and the desire of the aiji-dowager to subvert her great-grandson. His version states that Damiri-daja is being held prisoner and abused, and that Tabini intends to take her daughter from her.”

“One is not surprised he would lie,” Bren said.

“The troubling matter is that these lies have a purpose and a clear deadline, beyond which they will start to unravel.”

“The birth of the baby. News coverage.”

“We have concerns. Lord Komaji’s bodyguard is not that highly ranked: he has somewhat the aiji’s problem. But four other, higher-ranked teams have moved into Ajuri and we cannot get at their records even to find out the names involved. We have access that should be able to do so. But that access does not turn up these particular records.”

“Shadow Guild?” That splinter group lurking within the Assassins’ Guild. The driving power behind so much of what had gone wrong in recent years.

“We have that concern. We know that that organization was not all located in the Marid. And we know some that are dead. But we have not accounted for others. That is one matter. Lord Ajuri with his own aishid poses no great threat. We are no longer sure that it is justhis aishid protecting him, or even that he is the one giving the orders in Ajuri district. Second, Lord Tatiseigi has persistently offered Damiri staff from his estate. We advise against this and have advised Tabini-aiji to that effect. We have also advised Lord Tatiseigi’s household to keep him from going home until further notice.”

That, for a tired brain, required two thoughts to parse. Then he did. Damiri had been born at Tirnamardi, Lord Tatiseigi’s estate, in Atageini territory. “Damiri’s father was in that house,” he said.

“He was resident there for a year and a half,” Jago said.

Servants moved into other houses as lords married: they formed associations, left, or stayed on as their lord moved home, at the end of a contract relationship, or in its breakup. They were a lingering and troublesome legacy of any ill-fated marriage between clans.

“You think Tirnamardi is infiltrated,” he said. “A servant who came in with Komaji.”

“An assassination attempt against Lord Tatiseigi from within is not our chief worry, given Komaji’s rank at the time, the disposition of Guild-trained servants usually not running to violence. However the leaks on that staff we have generally attributed to the Kadagidi relationship with that house—may not all flow in the direction of the Kadagidi. Or not onlyin that direction.”

Kadagidi. The usurper Murini’s clan. Neighbors and one-time associates of the Atageini, a relationship which had, over time, gone very, very bad.

There went all inclination to sleep. How,he wanted to ask, but Jago had already warned him she could not say.

The Kadagidi were not in attendance at the current legislative session, and would not be, by their announced intention: We are taking a year of contemplation and assessment . . .

Like hell. They would not be in attendance because they had not yet been permitted to show their faces in court. They were Murini’s clan. The usurper had been theirclan lord, though not a popular one. Aseida, the new lord of the Kadagidi, had bodyguards who claimed to have been attached to Aseida from childhood, but . . .

But . . . there was some question on that point. It was an ongoing investigation. Algini had revealed, in one of his rare, need-to-know briefings, that Aseida, lord of the Kadagidi, was nothing but a figurehead. Algini believed the true force within the Kadagidi was one Haikuti, seniormost of Aseida’s aishid. Haikuti was a man Algini didn’t trust. Tano had said Haikuti should be taken out, but that that would simply scatter the problem.

And, he’d said, Haikuti might not be acting on his own. That he might have a superior hidden deep within the Guild.

Now nameless senior teams had been moved into Ajuri, to call the shots for another noticeably underpowered lord.

Someone able to position units in the field. He had this image of some senior administrator up in Guild Headquarters, quietly moving the right people about like pieces on a chessboard, somebody the honest Guild would never suspect . . . shuddery thought.

When they’d come back from space, there’d been an immediate house-cleaning in the Assassins’ Guild, retired members coming back to take their old offices and Murini’s supporters leaving town in haste.

They might have missed one, however, someone in a position to affect records, cover tracks, and protect others who should have been caught.

“Are you saying Kadagidi is tied to the Ajuri, Jago-ji?”

“We know at least that a leak in Tirnamardi ran to both the Kadagidi andAjuri—regarding one matter: the specific names of the servants offered to Damiri-daja. One,” Jago added with a grim laugh, “was misspelled the same way in both instances.”

He had for several months been a little worried about Ajuri—a minor clan, head of a minor association. Minor in every way but one: being Damiri’s paternal clan.

Tabini had married Damiri because of her Atageiniconnections. Atageini clan, Tatiseigi’s, was a solid, and important, key in the ancient Padi Valley Association.

And Atageini had supported Tabini in his return—at the risk of its entire existence.

Only then, once the tide had started to turn, had Ajuri shown up and joined Tabini’s cause, which was being fought on Tatiseigi’s land. They’d arrived late: they’d tagged onto Tabini’s triumphant return to Shejidan—and once safe in Shejidan others of the family had come in, all anxious to cluster around Cajeiri and Damiri and her father. Her aunt, her cousins . . . all had arrived full of solicitation and professed support.