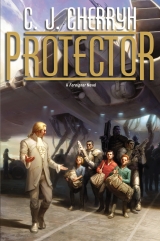

Текст книги "Protector "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

Then he told them story after story about Grandfather, including the night Grandfather had tried to get into the apartment when he was there with just a reduced staff and the servants. He told about his father banning his grandfather from the Bujavid, which really meant he had to stay out of the city, too.

Gene said, after a little silence, “If you act like that on the station, you get arrested, and they cancel all your cards and keys, and there you are, until they figure out how dangerous you are.” Gene added, with a downward glance, “I lost all my cards for sixty days, this year. But I was right.”

“I let Gene use mine,” Artur said.

“I got him into places,” Irene said. “And Bjorn did.”

They would have done that. Cajeiri entirely approved. And Gene told him why he had gotten in trouble—he was trying to get into the atevi section of the station where humans were not supposed to be—like the mainland and Mospheira.

And Gene told what it was like to get arrested on the station, if one did not have a person like mani to straighten things out, or a father to call on, just one’s own cleverness, and the cleverness of one’s associates. He made it funny, even if he had been worried at the time. For a while, listening to their adventures on the station, it was like being back on the ship.

His guests wanted to hear, too, about the escapes he had had, and how it was, when he had flown back with mani and nand’ Bren and they had had to do all sorts of things, like riding on a train with fish, to get here to Tirnamardi without being shot or caught. He had written about it in the letters, but he had been very careful what he wrote, then, especially careful about naming names; and now they wanted to hear it all, through two rounds of tea and cakes.

They had gotten down to the shells falling on the lawn at Tirnamardi, and the stables being wrecked, and young Dur landing his plane, and—

A black streak bounded for the top of a chair.

Thatcould not happen. Boji had his harness on. His leash was clipped to the cage.

Boji took another bound, toward the cage, and Cajeiri leaped up. “Close the window!” he yelled at Lieidi, who was closer, and ran to do it himself.

They all moved, knocking chairs aside, and Boji panicked. Boji dived straight for the open window, dodged Lieidi’s hands, and was out the window.

“Gods less fortunate!” Cajeiri leaned out over the sill, as far as he could, and heard his bodyguard, who had been caught by surprise, object to that effort, warning him not to try to reach too far.

Boji was down on a line of stonework trim, just out of reach. Cajeiri stretched further, felt hands on his coat, not pulling him back, but being sure he stayed in the window. “Boji,” he said quietly, reasonably, holding out his hand. “Boji, come back. Do you want an egg?”

Boji looked at him round-eyed and frightened, then ducked down and skittered right down the sheer wall below, using his clever little fingers to find the joints in the masonry.

“Go out, nadi,” he heard Lucasi say to someone, “try to get him from below.”

“Boji,” Cajeiri called, holding out his hand. “Boji, the game is over. Come back.”

Boji stopped, down by the next tier of windows, and looked up at him.

“Get me an egg,” Cajeiri said, upside down, and with the blood rushing to his face and his hands.

“Egg,” he heard Veijico say, as the door of the suite opened and shut, and he could heard his guests’ voices, offering to help.

He could see the harness and leash on Boji, or about a hand’s length of the leash, and a ragged end where Boji had chewed it through. He lay across the windowsill as far as he dared.

“Egg, Boji! Egg!”

“Nandi.” That was Lieidi’s voice, and he did not leave the window or make any sudden move that might frighten Boji. He just held out one hand backward, and when an egg arrived in it, he slowly brought it down and offered the egg clearly to Boji’s view.

Boji had climbed down another little bit. The movement had gotten him to look up, and Boji did see the egg: the fixed stare of his golden eyes said he had.

“Come on,” Cajeiri said. “Come on, Boji, Boji, Boji.”

Boji was definitely interested. Cajeiri held the egg to make it completely visible.

“Boji? Time for your egg!”

Boji started climbing up the wall, one large stone and the other, his thin little arms holding him as strong little hands found a hold on the stones.

“Hold my legs!” Cajeiri said, and more than one person grabbed his legs and held on. He leaned a bit more, and Boji climbed after the egg.

Boji reached up to snatch the egg, Cajeiri positioned his other hand to grab the harness, and just then someone came running around the corner of the house below.

Boji looked down, screeched, bristled up, and took off diagonally, far, far across the wall, headed for another open window, not in their suite. He reached that window, clung just outside it.

Gods. Cajeiri counted windows, divided, trying to figure how many rooms that was and what suite Boji had gotten to.

Great-uncle’s.

“Boji! Come back! Egg, Boji!”

Boji disappeared into the window.

Cajeiri began pushing at the sill and trying to get back inside, intending to run to Great-uncle’s suite, knock on the door and avert disaster . . . but just then Boji came flying out the same window and came scrambling back toward him across the stonework, chittering and screeching. He was almost to the window, then veered off in renewed panic, diagonally downward, while the person below—Jegari—waited there to try to get him.

“Take the egg!” Cajeiri yelled down, and dropped it. Boji had descended almost to Jegari. Then that egg went by and Jegari caught it with a sudden move. Boji suddenly screeched, leaped away from the wall, clean over Jegari’s head, and took out across the lawn toward the stable fence.

“Damn!” Cajeiri cried, and began struggling to get back in, at which several people pulled him in and set him upright. “He went into Great-uncle’s suite and came out! Now he has gone down into the stables! Come help me!”

“Nandi,” Veijico protested.

“He will not regard you,” he said, and saw Eidi hurrying to get his outdoor coat from the closet. “Never mind the coat, nadi!” He ran for the door, and his guests and his bodyguard ran after him. “Bring more eggs!” he cried, and went out the door, followed by whoever could keep up with him.

Guards in the hall were in short supply today, mostly at the other end, and Great-uncle’s doors were standing open—possibly becauseof Boji—but the guards were looking in the wrong direction. He dived down the servant stairs, down and down, with his bodyguards and guests pounding down the steps behind him. He caught the wall to make a tight turn where the stairs gave out, and headed for the little side hall and the stable side entry, where there were two guards.

“Do not stop us, nadiin!” he cried, waving at them to open the door. “Boji has run for the stables! Open!”

They did, looking confused and dismayed at the outbound rush.

He ran out—they had collected a trail of Uncle’s guards from the lower hall and the door, following them, and he heard Lucasi say, in Guild directness, “The young gentleman’s parid’ja escaped into the stables, his aishid pursuing. Quiet! Do not alarm it!”

This, while they were still running. Three mecheiti who were out in the pen had their heads up to see what was going on, rumbling and threatening—and there was Boji, walking the railing, near the stable itself.

“Boji!” Cajeiri said. But Boji was having none of it. He made a flying leap for the stable wall and swarmed right up it onto the roof.

He started to go closer.

“Nandi!” Lucasi exclaimed, putting out a hand to prevent him. He stopped.

But so had Veijico stopped, and every Guildsman, all at once.

But not because of the mecheiti. The Guild were suddenly listening to something only they could hear.

“Alarm,” Lucasi said. “Into the house, everyone. Now!”

Cajeiri’s heart leapt to double-time. It was trouble. Danger. General alarm.

“Run,” Cajeiri said to his guests, waving them back toward the house. It was his job to translate for them, to get them safely back inside. His bodyguard was doing what they had to do, and as more of his uncle’s guard came around the front of the house, weapons in hand—they ran up to the back door.

It was shut. Locked. Cajeiri pounded his fist on it, shouting, “Nadiin!”

Immediately it opened, in the hands of one of Great-uncle’s older house guards, who let them back into the safe dim light of the lower foyer.

They could stop there and catch their breath.

Boji had escaped, and he had no idea how far Boji would run. But there was something far, far more scary going on. The halls echoed with people running. Guards were moving into position, checking what they were assigned to check.

And others were out there near the stables, looking for someone.

“What happened?” Gene asked, bent over and panting. “What’s going on?”

“One has no idea,” Cajeiri said.

• • •

“Stable side door is secure, nandiin,” Banichi said, standing listening to what Guild could hear, and Bren and Jase could not. “The first alarm is accounted for. The parid’ja seems to have gotten loose. Jegari made an authorized exit in pursuit. The young gentleman and his guests exited, authorized. He is now inside with his guests, and safe. The parid’ja is still on the loose.”

“Could that have set the alarm off?” Bren asked, but just then Algini and Tano, who had gone outside, let Kaplan in.

“Sir!” Kaplan said to Jase.

“We’ve got a motion alarm,” Jase said to Kaplan. “North end of the house. The kids are downstairs, the little animal escaped its cage, and we’ve got some confusion going on out by the stable—but surveillance has picked up a more significant movement about twenty meters out. It appeared, then disappeared into the house perimeter—into range, then gone like a ghost.”

“Something came out of the house shadow,” Jago said in Ragi, “then went back in.The parid’ja is too small to trigger an alarm, nandiin-ji. This was an unauthorized exit, and someone came back in.”

“And is inthe house,” Bren said.

Banichi said. “The young gentleman and his guests have been escorted upstairs.”

“Condition yellow,” Jase said to Kaplan. “Go advise Polano. Stay on this floor. Keep in touch.”

“Yes, sir.” Kaplan saluted and left.

“Taibeni are saddling up,” Banichi said, “but they will not come within range of the house stables. One doubts they will find anything. A malfunction—a blowing scrap lofted on the wind, to the roof . . . it might be either. But we had a great deal going on at once just now, and Komaji’s assassination is still unattributed. We cannot dismiss this.”

“Yes,” Bren said, asking himself what in all reason butan exit from the building could have caused that alarm.

Evidently whoever it was hadn’t kept going, but had come back inside again. A servant who’d accidentally caused an alarm should be contacting house security immediately and explaining the problem.

All the youngsters were apparently accounted for. Theyhad gone out the other door, come back in when the alarm went off.

“This isn’t good,” he said to Jase. “We have a serious worry, here. I don’t want the kids spotting that little creature and creating a problem.”

“I’ll go find them. Make sure they understand.”

“Do,” he said, relieved to have someone covering that angle.

The people the dowager’s staff had sent to Tatiseigi weren’t novices in any sense, and Cenedi had furloughed every servant and guard whose records gave any doubt. None of the ones still on duty were the sort to forget the alarms and sensors they’d installed and blunder into them. Even the youngsters had gone properly past a checkpoint and come back the same way. How did one avoida checkpoint?

Banichi spoke to someone in verbal code.

And Algini and Tano came in from the hall.

“There seems no present danger,” Algini said. “Nor any reason at the moment to raise the level of alert. But we have asked Lord Tatiseigi to order all persons assigned to an area to stay in that area, and not to have staff moving about until we resolve this matter.”

That seemed a very good idea, in Bren’s estimation. “Is there any word from the capital,” Bren asked, “or should one be asking that question?”

“There is no alarm from the Bujavid,” Banichi said. “We have Taibeni moving on foot to the site of the disturbance, to locate any visible clue, and in case there is another such movement.”

Jago had been listening to something, sitting silent at the side of the room. “Word is now officially passing,” she said, standing up, “that the assassination this morning was carried out in a Guild manner. There has still been no public notice of a Filing.”

Without a public Filing.

No way was that legal, under any ordinary circumstances. A within-clan assassination could be kept quiet—but it still had to go through Guild Council to show cause and it required substantial support within the clan.

“Gini-ji,” Banichi said quietly, and Algini looked Banichi’s direction a moment. Then Algini nodded.

“Bren-ji,” Banichi said. “Algini will tell you something which the dowager knows—but Lord Tatiseigi does not. This has been affecting our decisions and our advice. This is the information we sent Lord Geigi. We are not, at this point, briefing Jase-aiji. This regards the inner workings of the Guild, and howthe coup that set Murini in power was organized, how the organization persisted past Murini, and why Tabini-aiji barred Ajuri from Shejidan. The aiji also is informed. Whether he has informed the aiji-consort is at his discretion. We have urged him not to.”

Answers. God.

If they had figured all thatout—on the one hand it was possible they had found what they had been trying to find for most of the last year; and on the other it was possible what they had been trying to find had located them,and this whole rearrangement of key individuals and their security was under threat.

Algini rarely gave anyone a straight and level look. He did now, arms folded, voice quiet: “We have known much of this since the affair on the coast, Bren-ji. Information we sifted out of the Marid confirmed what we increasingly suspected: that Murini was no more than a figurehead. Convenient, capable of some management, yes, but he was at all times only nominally in charge. He appeared. He gave orders. But there were individuals who pressed a more organized agenda on him. That agenda involved isolating the aishidi’tat from the station—which they accomplished, as you know, by grounding all but one shuttle. Once isolated, they intended to put a completely new power structure in place in the Bujavid, and, once the aishidi’tat was secure under their rule, to restore contact with Mospheira and the station. Geigi would be removed in some fashion, with the specific goal of putting the atevi side of the station—and its capabilities—under their control.”

Bren pressed his lips on a burning question and Algini said: “Ask, Bren-ji.”

“ Isthe station compromised? Havethey agents up there?”

“No.”

Bren took a slow, deep breath, greatly relieved. Without firsthand knowledge of the station, any hope of threatening it as outsiders was sheer fantasy. Atevi in general simply had no idea what Geigi could do from his post in the heavens.

“Needless to say, this goal was kept very quiet. Murini’s publicstance was againstthe new technology, which touched on conservative aims, and led certain individuals to accept Murini as backing traditionalist views. Tatiseigi was safe, despite the Atageini feud with the Kadagidi, because the last thing the powers in charge wanted was to antagonize the Conservative Party by assassinating an elderly man and a head of the conservatives. Tatiseigi at no time supported Murini. He remained an uneasy neighbor of Murini’s clan, even a defiant one. But he remained, as they thought, harmless and useful.”

And hadn’t thatassessment backfired, once Tabini returned?

“As to the means by which the coup was organized, Bren-ji, and this leads to information the Guild does not discuss, regarding its internal workings—there are Guild offices traditionally reserved for members from the smallest clans. For centuries, this has been the case, so as not to allow an overwhelming power to gather in the hands of the greater ones.”

That was not something humans had ever known.

“The Office of Assignments,” Algini said, “is such a post. It is a clerical office, with what would seem a minor bit of power. It does two things. One: it keeps records of missions and Guild membership. And two: it makes recommendations for assignment based on skills, specialization, clan—there are in fact a number of factors involved in designing a team for a mission, or a lasting assignment.”

Algini relaxed a degree and leaned against the buffet edge.

“Historically, and this is taught to every child, the same document that organized the aishidi’tat centuries ago also reorganized the guilds—at least in the center and north of the continent—insisting that the Office of Assignments of all Guild personnel should attempt to find out-clan units to assign within the clans, rather than permitting the clans to admit only their own. Theoretically, this would place the whole structure of the Guild under the man’chi of the aiji in Shejidan. The theory worked to make the guilds far more effective, to spread information, to stabilize regional associations, to unify the aishidi’tat in a way impossible as long as clan man’chi and kinships overpowered man’chi to one’s guild. Without that—the whole continent would not have flourished as it has. The East and the Marid declined to accept the out-clan rule, and these regions have remained locked in regional feuds, exactly as it was before the aishidi’tat, to their economic and social detriment. The aiji-dowager has made some inroads into the tradition in the East—one need not say—and the new legislation is bringing change to the Marid.”

A pause. A deep breath.

“Historically, then—the out-clan provision has worked. And—for much of the history of the aishidi’tat, the Office of Assignments of the Assassins’ Guild has done its part well. It has kept its records, formed teams, and sent its recommendations to other offices to be stamped and approved by the Guild Council. There are so many of these assignments across the continent . . . it isroutine. The stamp is automatic. One cannot remember there ever being a debate on them. Most often the local authority accepts, at its end, and the assignment is recorded. Understand, the Office of Assignments is a little place, smaller than this room, except its records-room. It is notcomputerized. The current Director of the Office of Assignments has been running that office for forty-two years. He has his own system, and he has resisted any technological change. He refuses to wear a locator, he will not accept a communications unit. The wits have it that he would have resisted electric light, except it had been installed the day before he took the office. It was not quite that long ago, but modernity does not set foot there. His name is Shishoji. And he is Ajuri.”

God. His administrator with the chessboard. A fusty little old man in a clerical office. A little old man who happened to be Ajuri.

“One had begun to suspect,” Bren said, “that this might involve some individual with an agenda.”

Algini nodded. “On the surface, it seems a little power, but placed in the hands of a person with an agenda, it is a considerablepower—to know all the history of a team, and their man’chi, and to make assignments the Council traditionally approves without a second glance, before it gets down to its daily business.”

A system grown up over time. A man sitting in that office for four decades, moving Guild personnel here and there by a process that had no check and was a matter entirely of personal judgment. . . .

It was a terrifying amount of power, in the hands of someone who saw how to use it.

“How can the Guild have been so careless?” Algini asked, rhetorical question. “Senior members have known him for years. He is quiet. Efficient. The wits find him amusing. He has become an institution. His assistants—he makes thoseassignments, too—do things exactly as he likes them done. A minor officeholder may also do a few favors for his own clan, and one would not call it improper. Careful selection of Guild members, to support a lord of Ajuri—or Damiri-daja—who could question it?”

Oh, my God.

“This is terrifying, Gini-ji.”

“Less so, now that we know where to look. —Damiri-daja may or may not know the situation. It is within Tabini-aiji’s discretion to tell her. —We have been, for the last while, reviewing our own associations within our Guild, personally informing those we know are reliable, and trying notto make a mistake in that process that would alert Shishoji-nadi that we are targeting him.”

“Do you think he set up the mechanism that supported Murini?”

“Very likely.”

“And the last two assassinations within Ajuri . . . were they at his direction?”

“Difficult to say—this man is exceedingly deft—but we suspect so, yes. Shishoji had, in the prior lord of Ajuri, a man who would support Murini. When Murini fell, and the Ajuri lord decided to change sides and take advantage of his kinship to Damiri-daja, we suspect Shishoji feared the man would tell Tabini-aiji everything once Tabini’s return to power was certain. That lord died quite unexpectedly. Komaji immediately stepped in, then began to behave peculiarly. He attached himself as closely as he could to the aiji’s household, did not spend much time in Ajuri, was trying to find a residence in Shejidan.”

“Possibly he understood his situation. Possibly he did notparticipate in the prior lord’s assassination.”

“It is entirely possible. Komaji may have known from the start that he had information that could, if he dared use it, place him in Tabini-aiji’s favor—if he was absolutely sure Tabini was going to survive in office. Unfortunately for him, Damiri-daja had staff that were not only a threat to Tabini-aiji—they were watching Komaji. We suspect he was trying to gather the courage to make a definitive move toward Tabini-aiji. And when the Marid mess broke wide open, and the aiji seemed apt to make an agreement with Machigi that might bring the aiji-dowager more prominence—Komaji decided it was the time. Possibly he feared the aiji-dowager’s closeness to Tatiseigi. He was notinvited to the signing of the agreement with Machigi precisely because Tatiseigi was—and it was the aiji-dowager’s choice. This upset him—possibly because he saw his opportunity to break free of Shishoji was rapidly dwindling, and he feared he was under Shishoji’s eye. He went upstairs to the aiji’s apartment. He was refused admittance. And at this refusal, in high panic and absolute conviction Tatiseigi and the dowager meant to separate him from the aiji and from his grandson, he broke down in the hallway. His nerve failed him, he no longer trusted his own bodyguards, and when the aiji, beyond banning him from court, sent Damiri-daja’s bodyguards back to Ajuri along with him, Komaji had nowhere to go butAjuri. Once there, he remained non-communicative, secretive, and ate only the plainest food, prepared by one staff member. Then he made his last move, toward Atageini lands, with a handful of Ajuri’s guards, nothis own bodyguard. —Did anyone of that company survive, Jago-ji?”

“They are, all of them, dead, short of Atageini land.”

Algini nodded slightly, acknowledging that. “Not surprising.”

“Where was he going?” Bren asked. “What was he trying to do? Do we know?”

“We surmise that in the failure of all other options,” Banichi said, “he may have been seeking refuge here, in the house of his old enemy Tatiseigi, whose staff might get a message to the aiji-dowager, to his daughter, or to Tabini-aiji himself, offering what he had to trade. Likely he hoped that one of them would sweep him up and keep him alive in exchange for the information he had. He was not a brilliant tactician.”

One could almost find pity for the man. Almost.

“Nadiin-ji. How long has this . . . dissidence in the Guild been around? Did this Shishoji organize it?”

No one answered for a moment. Then Algini said:

“That is a very good question, Bren-ji. How long—and with what purpose? It began, we think, in opposition to the Treaty of the Landing.”

“Two hundred yearsago?”

“We think it was, at first,” Banichi said, “an organization within the newly formed Guild, a handful who were opposed to the surrender of land to humans. Originally they may have hoped to lay hands on stores of human weapons and simply to wipe every human off the earth. There were such groups in various places, and there was that sort of talk abroad. It did not happen, of course. No one found any such resource. Then, as we all know, the paidhiin were instituted. They were set up to be gatekeepers, to provide peaceful technology, not weapons. It is, perhaps, poetic, that you, of all officers of the court, have been such a personal inconvenience to the modern organization, Bren-ji. The paidhiin were, from the first human to hold the office, the primary damper on such conspiracies.”

“One rather fears that I have become their greatest hope,” Bren said, feeling a leaden weight about his heart, “and a great convenienceto them—in bringing atevi into space and putting the shuttles exclusively under atevi control . . . if their aim truly was to take the station.”

“No,” Jago said.

“In the station program, Bren-ji,” Algini said, “you have linked atevi with humans, economically, politically—even socially. You aretheir worst enemy. Youbrought reality home to Shishoji, we firmly believe it. You negotiated the means to put humans and atevi into association, which his philosophy called impossible. Younegotiated the agreement that put Geigi in control of weapons they are only just beginning to appreciate. The Shadow Guild planned, naively, to get into the atevi section, convince atevi living up there to wipe out all humans, overcome the armament of the station and the ship, and seize control of the world, using the station. This is, demonstrably, not going to happen. It would not have happened, even had Murini succeeded in getting teams onto the station. Shishoji knows, now, that amid all the technology the humans have given us, their most powerful weapons remain under the control of one incorruptibleateva, in the person of Lord Geigi. They could not succeed. Not on the station. Down here . . . Down here is another matter.” Algini glanced in Banichi’s direction. “I have asked myself, Nichi-ji, whether we could have seen it coming, and I do not think we could. Shishoji found changes proliferating and the world changing faster than he could adapt. He found himself in danger of irrelevancy. But there was also unease, in ordinary people both wanting and opposing the space program, at a time when there was considerable doubt as to human intentions—especially given the interim paidhi.”

Yolanda Mercheson. A disaster, who had notbeen able to convert her linguistic study into an understanding of atevi. She had tried. But she had not gotten past her own distrust of Mospheirans, let alone atevi.

Jase, meanwhile, had been with the ship.

God. Twenty/twenty hindsight . . .

“Tabini-aiji’s popularity was slipping. Lords were maneuvering to get a share of the new industry, even as public doubts arose regarding whether humans on earth or in the heavens had any intention of keeping their agreements. The conservatives and the traditionalists were gathering momentum in the aishidi’tat. And when a crisis came in the heavens, and it seemed humans might have lied to us, every pressure on the aijinate was redoubled. Tabini-aiji escaped assassination, but his bodyguards were dead, his staff was dead, Taiben had suffered losses and the Atageini were too weak to help. His attempt to reach the Guild met a second attempt on his life, and within hours it was announced Tabini-aiji was dead, that the majority of the shuttles had been grounded to protect the aishidi’tat from invasion from orbit—”

And Yolanda Mercheson had run for her life. He had heard the account before, but from a very different perspective.

“Within an hour of the announcement of Tabini’s death, six of the conservatives andthe traditionalists declared man’chi to Murini,” Algini said. It was a set of facts they all knew. But Tano and Algini had seen it all play out.

Banichi and Jago had been with him, the dowager, Cajeiri—and Jase—on the starship, headed out to try to deal with the Reunion situation.

“We do not see now,” Algini said, “that this situation will repeat itself. We have not changed our recommendation to the aiji and we have removed the one vulnerability we think gave the aiji’s enemies access to his schedule and his apartment.”

“It is the aiji’s belief, Bren-ji,” Tano said quietly, “that Damiri-daja’s staff, knowingly or unknowingly, supplied information to the conspirators. Tabini-aiji’s staff died. Certain of Damiri-daja’s escaped.”

“And returning with Komaji,” Banichi said, “came Damiri’s aunt, her cousin, and her childhood nurse. The nurse, oldest in the consort’s service, stayed on when the others went back to Ajuri. When we recovered the records from the situation on the coast, and began to peel back the layers of the Shadow Guild, when we began to realize that Murini was more figurehead than aiji, and when Komaji had behaved as he had, we bypassed the aiji’s guard to advise Tabini-aiji to discharge the consort’s staff and bodyguard immediately. We wanted them detained. Unfortunately—and we have not had a clear answer about the confusion in the order, they were simply dismissed.”

Damn.

“At the moment,” Algini said, “we have asked Tabini-aiji to observe a restricted schedule, do business by phone and courier, and that he and Damiri-daja stay entirely within the guard we have provided. The aiji has confidence in the consort’s man’chi. She was with him through his exile, her bodyguards were all assigned to her service—by the process you now understand—on their return from exile, and they were all Ajuri folk, as a particular favor to her. Afterward, the night of the reception for Lord Geigi, she told the aiji-dowager that she was close to renouncing her connections with Ajuri.”