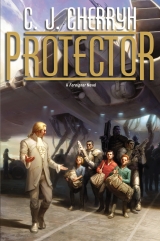

Текст книги "Protector "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 22 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

“I should then ask my aishid what I should answer, and I doubt you would advise that, in a household under the aiji’s ban.”

“They may simply bar the door,” Jago said.

“Frightening them is surely worth something. And meanwhile we have them pinned down, we can interdict anyone who comes outof that house, and Lord Geigi candrop something on their land, with a great deal of precision.”

“Bren-ji,” Banichi said, “your resolution never to advise your bodyguard is in serious breach.”

“Then advise me. I shall certainly hear advice. But I cannot lose you. And the dowager cannot lose Nawari. You—and Cenedi’s team– youhave more importance than I do, when it comes to a fight inside the Guild. You know the names and histories of these people. You have accesses nobody else does. You are notexpendable and I am, comparatively, in this part of the fight. If it requires a readjustment in your man’chi—make it. We cannot risk you, and I do not countenance Cenedi risking Nawari, either. He is doingthis because he needs you, and he is staying meticulously within the law—but I do not agree he should. We should go in there prepared to deal damage, and Jase and I should make the approach, because our status gives youthe right to take them on without a Filing on our side, if they compound their offense with one bullet headed our direction. If there is any legal question—any political question that follows this—then that is myexpertise, nadiin-ji, and I will defend this decision. I would look forward to dealing with anycounterclaim this old man in the Guild or his allies can make.”

There was a long silence. “We shall have to talk to Cenedi,” Banichi said, “and advise Tano and Algini. Not to mention the dowager herself. Speed in this is advisable. We do not know whennews from the south may reach Guild Headquarters. —Jago.”

“Yes,” Jago said, got up, and headed for the door.

Banichi also left. Theyhad things to arrange. Cenedi to consult.

He, meanwhile, had to talk to Jase—urgently.

• • •

“We have a problem,” was how he started the explanation, while Jase, roused from sleep, sat amid his bedclothes. Kaplan and Polano had opened the door, and stood in the little sitting-room, in their shorts.

He explained it. Jase raked a hand through his hair; then said: “We’re in. Can we get a pot of that strong tea in here?”

“Deal,” he said. “I’ve got a spare vest. Choice of colors, brown or green, and bulletproof. I’ll send it with the tea.”

“I’m not particular.” Jase raised his voice. “Kaplan. Polano. Full kit, hear it?”

“Aye, captain,” the answer came back, and Bren headed back through the sitting room, to get back next door and send Supani and Koharu in with the requisite items. Tea for three. One vest, proof against most bullets. He and Jase were about the same size.

The dowager could still countermand the operation, but while he was dispatching Supani and Koharu, Tano and Algini came in to gather up needed gear, and it was clear that that wasn’t happening.

“The aiji-dowager,” Algini said, “has sent for the bus.”

“We do not know the capabilities of Jase-aiji’s guard,” Tano added. “We understand they are considerable.”

“They are,” he said. He put on the green vest: he had sent the brown brocade over to Jase. He had on a reasonably good shirt, his good beige coat, and Koharu handed him his pistol and two spare clips. He tucked those into his coat pockets.

Banichi came back. “The bus is well on its way. The dowager has waked Lord Tatiseigi, who is not yet coherent, and she has instructed Cenedi to tell me to tell you to stay behind your bodyguard.”

“One earnestly promises it,” he said. It somewhat troubled him that Banichi seemed cheerful—in a dark and businesslike way. Banichi and Jago both had looked worn and tired less than an hour ago, when they had explained to him that they had been outranked on the mission. Now they were full speed ahead—and he had to ask himself whether he had put temptation in their path.

But he was right,damn it all. Putting Nawari in there to try to draw a response was the best of a bad job. Nawari was a perfectly legitimate target. They couldnot risk the dowager going over there—though she wasn’t a legitimate target. And Cenedi was going by the book, against a Guild problem that wouldn’t.

He was far from as cheerful as his aishid in the prospect—it wasn’t in his makeup. But he’d been through hell down in the Marid, and he wasn’tGuild, with a traditional bent. He’d begun his career with a far simpler book, a dictionary of permitted words—and he’d watched that dictionary explode into full contact, up on the station.

He’d watched it work. There. Down here . . . he’d watched the world change, and he understood atevi for whom it had changed too fast. His job—his job,as Mospheira had originally defined it—was to keep the peace and recommend the rate at which star-faring technology would be safe in atevi hands.

In that sense, he’d failed miserably. But eventshad proceeded too fast, there’d been no time to temper the impact, and now . . .

A descent into the dark ages that had preceded the organization of the aishidi’tat would put a hellof a lot of inappropriate technology into inappropriate use. Hell if he was going to watch that happen.

And the instant he’d seen Jase, with a captain’s personal defenses, descending from the shuttle with the children—he’d had a little chill thought that Lord Geigi had sent him. Lord Geigi had gotten that briefing on his way to orbit. Geigi knew the situation inside the Guild. Knew exactly howit had to be stopped.

Geigi might have recommended the children come ahead. And he might have given the facts of the situation to the other captains, who were hell-bent on seeing the children’s mission work out, not in some ideal situation, but involved in the world as it was.

Jase had come down with just his bodyguard. The ship-paidhi.

With his bodyguard. From the starship.

Geigi, he suspected, had sat back at his desk, scarily satisfied.

17

The bus trundled onto the drive at the very edge of dawn, a slight blush to the sky above the hedges. It had a secret, sinister look, its red and black both muted by the dim light, except where the front door light cast its own artificial brilliance.

Black, too, the uniforms of the Guild who quietly boarded, stowing some pieces of heavier armament Bren hoped did not come into play. The rest, and the electronics, were hand-carried briskly toward the rear. It was war they were preparing.

Bren waited at the foot of the steps. His aishid was in conference with Cenedi and Nawari, beside the open door of the bus. Jase was on his way.

So was Jase’s bodyguard—in armor that trod heavily on the stone steps as they came out of the house, servomotors humming and whining constantly. Jase came down the steps of Tirnamardi, and Kaplan and Polano followed, weapons attached to their shoulders, not swinging free, but held there, part of the armor itself. They were taller, wider than human—taller and wider, even, than most atevi, and gleaming, unnatural white. They carried their helmets, and their human faces looked strangely small for the rest of them.

“That should make an impression,” Bren said, as Jase joined him—Jase in his own blue uniform, with, one surmised, that borrowed vest beneath it.

“Projectiles will ricochet off the armor,” Jase said. “Your people need to know that.”

Jase had a com device on his ear, and behind it.

“I’ll remind them,” Bren said. “Is that two-way communications?”

“With my own, not with yours,” Jase said, as they went toward the bus. Bren stopped to relay the information to Banichi, then climbed up the bus steps and went to his usual seat.

“Sit with me,” Bren said to Jase. Banichi and Jago were coming aboard, and took seats across the aisle. Tano and Algini went further back in the bus, where the dowager’s men had gathered in the aisle by the galley.

Last of all, Kaplan and Polano came aboard, rocking the bus somewhat and occupying the space between the driver and the door—an armored wall.

One of the dowager’s young men held the driver’s seat. He shut the door and put the bus gently into motion on the curving drive.

Dawn was coming fast. There was almost color in the stone of the house as it passed, in the straggle of woods that ran down the side of the house.

The situation, with Kaplan and Polano blocking out the view in front, and the hedge scrolling leisurely past the side windows, assumed a surreal feeling—a journey like others this bus had made in its brief service; but different. Far more desperate. Before, they had gone in with some hope of negotiation. Now, admittedly, they were not going in any hope of it.

It was a northern house they meant to visit—and all the accumulation of antiquities, associational ties, and politics that went with it—and this one, troublesome as it had been, was one of the core clans of the aishidi’tat. Political fallout was inevitable.

He had indirectly consulted with Ilisidi and Tatiseigi. But those two still had deniability. Tabini’s hands were nowhere near the situation. Ilisidi and Tatiseigi were having breakfast. Geigi was in the heavens. Had they met with the paidhiin to spark this retaliation? Absolutely not.

In the list of things one had planned to do to manage a boy’s birthday in some degree of peace and security—deliberately staging an incident between the two oldest houses in the Padi Valley had not remotely been on the horizon.

But here they were.

And if hehad been in this kind of situation before, on this bus, and knew its resources—Jase hadn’t, and didn’t.

“Snipers are at issue,” he said to Jase. “Keep your head down if—and when—shots start flying. We have armoring below the windows: the front windows are bulletproof. The tires will hold up against most things. The roof is reinforced. If you have to duck, get as low as you can below the windows and don’t put your head up.”

The kids were, one hoped, sleeping off their late night . . .

As the bus gathered speed toward the gates that would let them out to the road.

• • •

There had been the most amazing sight in the hall: Kaplan-nadi and Polano-nadi in their armor, heading toward the stairs, making that weird racket as they walked. The thumping tread had waked Boji and Boji had waked all of them, and Antaro had looked out the door and told them what it was. So Cajeiri and Gene had gotten there just in time to see Jase-aiji’s bodyguards go down from the landing and out of sight.

“Stuff is still going on,” Gene had told Artur and Irene, who had arrived too late to see anything. “The captain’s guard is out in armor and everything.”

“What isgoing on?” Cajeiri asked his aishid, who were all up and dressed. Boji was rattling his cage and setting up a fuss, shrieking and protesting.

Antaro had gone out to find out from the guards in the hall what had gone on, and why Jase-aiji’s guards were in armor.

“They caught the intruders last night, nandi,” Antaro came back to report, after far too long. “We were told the emergency was over—that we should all go to bed. They maintain the emergency is still over. They have no idea why the ship-folk are in armor.”

“Everyone,” he said. “Clothes. Taro-ji, call and find out what is going on.”

“We cannot, nandi,” Lucasi said. “We are getting a short-range red. That means no communication at all. Shall I go downstairs to find out?”

“Go,” Cajeiri said. Eisi was up and dressed. Lieidi was nowhere in sight yet. “We need our clothes, Eisi-ji,” he said. “Quickly. Never mind baths. We may have to go down to breakfast to learn anything. Luca-ji, find out, while you are down there, if there isformal breakfast.”

• • •

The bus was not proceeding at any breakneck speed—far from it. And there was no space in the aisle at the rear—the dowager’s young men had sat down on the floor back there, rifles and gear with them, ready, and out of view of any observers.

“Nawari’s units have already moved,” Banichi leaned close to say. “We are pacing them on a timetable. That is why we are not up to speed.”

“Yes,” he said, acknowledging that, and relayed it in ship-speak to be sure Jase understood. “Nawari’s group is afoot. We are keeping pace with their movement. We’ll get there just before them—we know this distance, absolutely. Now we just go over and wish the Kadagidi good morning and see how mannerly they are. Unfortunately—I don’t think we’ll get a good answer.”

He watched the countryside roll past the windows. They’d made the turn onto the main local market road, such as it was, a long low track in a land of scrub and weeds. The road, parallel to the railroad tracks, connected the Kadagidi and the Atageini, and the desolate, unmown condition of the road said worlds about relations between the two clans. The only legitimate traffic between Kadagidi and Atageini territory all year had likely been railway maintenance vehicles.

Before that—before that, for two years, as Murini ruled the aishidi’tat, likely there had been very frequent patrols down this route, Kadagidi keeping an eye on the Atageini, in Murini’s name.

Change of fortunes, decidedly.

• • •

Breakfast was downstairs, and they were told to come down at their leisure. Great-grandmother and Great-uncle were already in the little dining room—Cajeiri knew that immediately by Casimi, one of mani’s secondary guards, being outside the door, along with Great-uncle’s senior bodyguard. And there was no room for four more in that room.

Casimi, however had seen them, and signaled them, so Cajeiri came and brought his little group—his guests, and his bodyguard—with him.

“One expected you might sleep late, young gentleman,” Casimi said.

“Jase-aiji’s guards were in the hall in armor. And where is nand’ Bren, nadi?” Nand’ Bren’s guard was nowhere in evidence in the hall, nor was Jase’s, and things seemed more and more out of the routine.

“Jase-aiji and nand’ Bren have gone to call on Lord Tatiseigi’s neighbors,” Casimi said.

“Kadagidi!”

“Exactly so, young gentleman. One requests you please do not alarm your guests. Your breakfasts this morning will be in the formal dining room. One is also requested to inform you that Lord Tatiseigi has planned a tour through his collections this morning after breakfast, at your convenience.”

Please do not alarm your guests.

And nand’ Bren and Jase-aiji had gone over to talk to the Kadagidi, after what had happened last night. That was about the most dangerous thing he could think of.

“What happenedlast night, nadi? We know about the intruders. We understand you caught them. Were they Kadagidi?”

“Dojisigi, nandi, but they had come here with the help of the Kadagidi.”

“Assassins’ Guild?” He was already sure of it. “After Great-grandmother?”

“Their target was your great-uncle, young gentleman. They claim to have had no idea your great-uncle would arrive with guests. They have apologized and stated they wish to change sides. So do not trouble yourself about that business, young gentleman: they are under this roof, but under watch. Be sure they are under watch. One understands you were able to recover the parid’ja last night.”

“Yes, nadi. He came back to the window when all that happened. But—”

“Kindly be very careful to observe house security today. We are strong enough to repel any problem—granted our young guests stay inside and with you. For your Great-grandmother’s sake—please be sure of their whereabouts at all times today.”

Casimi and his partners were such sticks.

“Yes, nadi,” Cajeiri said with a polite nod.

“Hear me, young gentleman: should you lose track of anyone, do not try to find the missing persons. Notify us and let us deal with the matter. We had two Marid Assassins living in the house garage when we arrived, and while we do not believe there are any other surprises in the house—consider any untoward occurrence a matter for us to know, immediately. Please assure me you understand this.”

In the garage.They had imagined intruders living in the basement . . . where Great-uncle was proposing to send them today, to tour the collections.

Casimi was a stick, and Casimi probably had never forgiven him for the tricks he had played on him, getting away right past Casimi’s nose: Casimi probably thought he was a thorough brat, too; maybe even that he could be a fool.

Which was unfair. He had been monthsyounger.

“Please do not share much of this with your guests, young gentleman. They should have a happy visit. And touring the collections will put you in a very safe part of the house today.”

“One thought we were worried about Assassins in the basement, nadi.”

“The basement has been searched very thoroughly, young gentleman. So has every room and closet in the house.”

What about the garage? he wanted to ask pointedly—but it being Casimi, who already had a bad opinion of him, he decided just to do as he was told.

“The formal dining room,” he said. “Thank you, nadi, nadiin.”

So there was nothing for it but to do as Casimi told them to do. He gave a second little bow, said, “Please tell my great-grandmother and uncle that we are very glad they are safe, nadi,” and to his guests:

“Breakfast is in the big room. We can say more there.”

• • •

Not that long a drive—and they were still in no great hurry about it—it was a leisurely cruise down the road. The sun was up, now, gilding the tops of dry weeds and the branches of leafing scrub. On any ordinary day, at this hour, he’d be having toast and tea and going over his mail. Right now his heart kept its own time, dreading the encounter and wishing they’d get there faster.

The bus nosed gently downward, the slope of the other side of the hill, and ran at just a little greater speed, breaking down weeds and small brush.

“Polano says there’s a structure on a hill, on the horizon,” Jase said quietly. Jase’s bodyguards had an unobstructed view out the windshield. They didn’t.

“That would be,” Bren said, “the Kadagidi manor house. Asien’dalun.”

He wished he could see the place. He urgently wished he could see what was going on, or whether there was any sign of trouble. But not seeing ahead of them was part of their protection—and he wasn’t about to get up and take a look.

Once they reached the estate, Guild protocols shouldswing into operation, but there was no guarantee they wouldn’t be met by mortar fire.

Lord Aseida, at this hour, would be having breakfast, or answering his mail, and the lord might continue at that, while his security asked, officially, using Guild short-range communications, who was arriving. When they did arrive, the house would open the door and the major d’ would come out, with his assistant, wanting to know officially and formally, for the civilian staff, who was arriving . . . this was a matter of form, the form having been devised long before radio.

The major d’ would ask, they would answer, restating their business.

Considering the circumstances, they would likely be asked to leave—a formal request.

They weren’t going to. That message would be conveyed to Lord Aseida, who would, at that point, have two choices: send his major d’ out to talk to the offended neighbors, in which case things would proceed eventually to a civilized talk between neighbors—or—Lord Aseida would send out his bodyguard to talk to the neighbors’ bodyguards.

The temperature would go up at that point.

But they had no contact yet. In point of fact, he expected none. And the bus would keep rolling as they skipped steps in the protocols . . . and as Nawari and his team did their best not to trip any alarms or traps, from the hole in the hedge to the side door of the house itself—necessarily a careful business; and if they did have to stop for a problem—that complicated things, considerably.

Haikuti, ifhe was on the premises, and if he was admitting to beingon the premises, would warn the bus to stop and to go back—while he’d be positioning defenses. Or possibly he’d let the bus come in, and position offenses. Whether or not the Kadagidi had already picked up movement to its northwest would dictate how and when the local bodyguard would react. A protest against an overland intrusion would certainly be in order—plus a threat to call Guild Headquarters and get the matter on official record, which the Kadagidi could make—and they didn’t dare.

“At this point,” Bren said to Jase, “it becomes a complicated dance. They’ll protest; we’ll say it’s a social visit. They may notice our people coming up overland. Then we see whether Lord Aseida comes out to talk. He shoulddemand to talk to me—which is his job—but we don’t think it likely he’s actually speaking for himself, or that he has any power at all over his guard.”

“Haikuti.”

“Exactly. Aseida’s either so smart he’s run everything all along, even through Murini’s administration—or he’s nothing. By all I know of Haikuti, he’d have no man’chi. Not to a living soul.”

“Aiji-like, in other words.”

“A member of the Assassins’ Guild can’t be a lord of any kind—legally. You can be in the Physicians’ Guild and happen to be lord of a province and serve in the legislature—there is actually one such. But the compact that organized the aishidi’tat drew a very careful line to keep the one guild that enforces the law entirely out of the job of making it.”

“Has it worked?”

“Yes. Until now. But we suspect Haikuti fairly well took power under Murini’s administration—and Shishoji had to move him there. How far under Shishoji’s control he is now—is a question. If anything should happen to me, I should say, tell the captains to protect Tabini, the dowager, Cajeiri, and Lord Tatiseigi. Four people. Get them up to the station if there’s no other choice. Theyhave the people’s mandate. But one bullet can send all plans to hell.”

“God, Bren. I sincerely take what you’re saying. But just keep your head down, will you?”

“I intend to. But a little risk, unfortunately, goes with the job.”

• • •

“So what’s going on?” Gene asked in ship-speak, once the servants were out of the dining room. “Where’s Lord Bren? What happened last night?”

It was upsetting to be questioned during breakfast. Great-grandmother would never approve of such behavior. But they were all at one table, Cajeiri, his bodyguards, his guests, and the mood was not at all festive.

“Nand’ Bren went to the Kadagidi,” he said, also in ship-speak. “Next door. Lord Bren and Captain Jase, too. With Captain Jase’s guard. To talk.”

It didn’t help the frowns, and just then a servant came in with another plate of spiced eggs and toast. “We are going to walk around the basement.” Cajeiri tried to change the subject entirely during the service. “Great-uncle’s collections are famous.”

“I wish we could go riding again,” Irene said. “If they caught those people—”

“Not that easy,” Cajeiri said. “We’re safe in the house. But still under alert.”

“For morepeople?”

“Not sure,” Cajeiri said. If they kept it to ship-speak, at least the servants would not realize they were being improper. “Don’t worry. All fine. But we don’t go outside.”

“Tomorrow?” Irene asked. And unhappily: “Ever?”

“Maybe,” he said, wishing he knew the answer.

Conversation limped along. He knew ship-speak for things on the ship, but he struggled for words about things on earth. And he had no words to explain the Kadagidi.

“Luca-ji,” he said quietly to Lucasi, who was good at talking to senior Guild, “see what else you can find out. You can do it after breakfast.”

“Yes,” Lucasi said, swallowed two bites of toast and got up from the table, leaving a whole piece of toast and an egg on his plate.

So his bodyguard was as desperate to understand the situation as he was.

• • •

The bus slowed to a stop. Bren took a look out the window, as much as he could see, which was scrub trees and pasturage, and a low fieldstone wall.

“We’ve come to a gate,” Jase said, having the report from Kaplan and Polano, who had the vantage up there.

“Whether they’ll open it will say something,” Bren said.

“We can take it down,” Jase said. “That’s no problem—if you need it.”

“We’ll see,” Bren said, and looked up as Banichi arrived beside his seat.

“When we get to the Kadagidi house, Bren-ji,” Banichi said, bypassing the question of modality, “we will bring the bus as far as the front porch, at an angle where sniping from the roof is not easy.

“Jase-nandi,—one understands the armor is good against armor-piercing rounds?”

Jase looked at Bren, wanting translation.

Bren gave it.

“Yes,” Jase said in Ragi, and nodded. “No problem, Banichi-nadi.” And in ship-speak: “Rules of engagement, Bren.”

Bren translated the question.

“Fire only if fired upon,” Banichi said. “Avoid servants and civilians.”

Bren translated that, too.

“This is the plan,” Banichi said to Jase, leaning on Bren’s seat-back. “We would ask Kaplan and Polano to go out the instant we stop, and take position to screen us from fire as we exit the bus.”

“Exit the bus,” Bren said, interrupting his translation. “Banichi-ji—”

“If the situation calls for it, Bren-ji, we all four will escort you out. Onlyif the situation calls for it. And, much as your aishid covets the honor of defending you, stay behind Jase’s bodyguards and do not go beyond one step from the bus. Your greatest danger is a sniper in the upper floors. Pay attention to that. We shall. The house will be on the right side of the bus and we will pull up close to the door to inconvenience targeting from those floors. A grenade remains a possibility. We can do nothing about that—except interest them in finding out what we have to say, and be aware whether those upstairs windows are open or shut.”

“Understood.”

“And, Bren-ji, you will notaccept an invitation to tea in this house.”

“I promise that,” he said with a startled laugh. But it did nothing for his nerves.

“The gate is opening,” Jase said in Ragi.

Banichi straightened. “So. We shall see.”

The bus started to move. The road between the gate and the Kadagidi front door was not as long a drive as that from Tatiseigi’s gate to the house. It was a gravel road, by the sound under the tires, and the bus gathered more speed than it had used thus far, not all-out, but not losing any time, either.

“They’re going to let the bus all the way up to the house?” Jase asked. “What if we’reloaded with explosives?”

Bren shook his head. “We’re the good guys, remember. Guild regulations. A historic site, and civilians. We’re supposed to finesse the situation all the way. And of course they’resupposed to talk to us, on their side, lord to lord. If they refuse to talk to us, we have an automatic complaint—for what it’s worth.”

“This is that ‘little risk’ you were talking about. Going out there.”

“Banichi’s thinking this through. He has a reason. The dowager’s men, back there, may get off, too; and if they do, keep the aisle clear. And if things do go to hell, just get down below the windows and let the driver follow his orders, one of which is to get you out of here.”

“God, you’re insane on this planet.”

“It’s an eminently reasonable system—when you’re not dealing with scoundrels.”

“The hell.” Jase levered himself to his feet and went up to Kaplan and Polano, delivering low, quick instructions of his own. Bren couldn’t hear exactly what he said, above the noise of the bus, but Kaplan and Polano nodded solemnly more than once. Jase clapped each on the shoulder and returned to his seat, while Kaplan and Polano started putting their mirror-faced helmets on—their smallest movements accompanied by a whining sound that rose above the roar of the bus on the gravel.

“They understand,” Jase said. “Those helmets have sensors. They can see behindthe wall. Three-sixty and overhead. They’ll know where we are and once they’ve mapped that, they’ll spot any other movement. I warned them about grenades. And snipers.”

“Is there going to be any complaint from the captains on this?” Bren asked. “Say I asked it. Urgently, I asked it.”

“Understood. And understand that they’re here to handle whatever my presence or those kids’ presence might provoke. I’dsay this is partly due to my presence. For the record.”

The bus had begun the curve that would lead it right in front of the house. Bren caught a scant glimpse of the stone facade, past Jase’s men, a blockish, formal Padi Valley style manor, in situation and aspect not unlike Tirnamardi.

A fortress, in the day of cavalry attacks and short-range cannon, with windows only on the high upper floors.

“The paidhi-aiji and the ship-aiji have come to call on Lord Aseida,” Bren heard Banichi say, talking on Guild communications while the bus rolled. The calm tones had a surreal quality, as if it were old territory, a scene revisited again and again. “They are guests of your next-door neighbor the Atageini lord, and they have been personally inconvenienced by actions confessed to have originated from these grounds. These are matters far above the Guild, nadi, and regarding your lord’s status within the aishidi’tat. Advise your lord of it.”

Time to pay the rent on the estate at Najida. He’d said it. Lordships came with responsibilities.

And one didn’tgive tactical orders to one’s bodyguard.

The bus gathered speed, took a gentle curve, and then ran into shadow, the Kadagidi house looming between them and the cloudless sunrise. A hedge passed the window, then a windowless expanse of pale stonework, ancient limestone, and vines, passing more and more slowly as the bus braked.

Full stop. Immediately the driver opened the door. “Go,” Jase said in ship-speak, and Kaplan and Polano immediately took the steps, jumped from the last one and landed on their feet as if the armor weighed nothing—gyros, Bren thought distractedly. Beyond the windshield, now that they could see, and about a bus length ahead, were low, rounded steps, a single open door, and black-uniformed Kadagidi Guild arriving outside to meet them with rifles in hand.

But the Kadagidi reaction stopped on those steps. Whatthe Guildsmen saw facing them beside that bus door, the world had never seen. That was certain. Kaplan and Polano had taken up position, mirror-faced, tall, and bulky, atevi-scale and then some.

“Bren-ji, come,” Banichi said, from beside Bren’s seat.