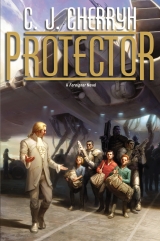

Текст книги "Protector "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

6

The oldest engine in regular service pulled up to the platform and small office, puffing steam—luck of the draw, last night, when it had been sequestered and prepared for its run, but it was fast, and it often pulled this particular set of cars.

There was not much to see at the train station, beyond the simplest of sidings, a line of blue-green trees, and, if one knew what one was looking at, a long runway that stretched out of sight behind the little transport office. The main buildings, a little outpost of the space program, were far in the distance.

A large, sleek bus was waiting, and a conveyor truck stood at the platform, ready to whisk people and baggage through a hidden gate to the spaceport itself, which operated in high security, behind fences and sensor-systems. It happened to be the oldest shuttle in the fleet that was waiting for Geigi, too, over that gentle roll of the land, but it was oldest only by months: that was how hard they had pushed, in the earliest days of the space program. It had been two weeks on the ground undergoing the sort of servicing the ground facility did best. And within hours, it would be winging its way across the ocean on a long ascent, up to where the blue of atmosphere gave way to the black of space.

The station’s modern world started here, with that bus, the conveyor truck. From this point on, Geigi would be too busy with procedures to be socially engaged. So it was prearranged that the paidhi-aiji was to go no farther than the doorway of the train car and that Geigi would immediately board the bus, no lingering about outside, and little to see, in this vast flat grassland.

“Well, well,” Geigi said, heaving himself to his feet, “one can only thank you, Bren-ji, for all you have done, from a very difficult beginning.”

“For you, Geigi-ji, my neighbor, an honor. Come back soon.”

“Nandi.” They bowed properly to each other, and moved toward the door, and their parting. Geigi’s staff was already shifting personal luggage out very efficiently, gently tossing things down, and Tano and Algini went outside to supervise the baggage car’s more extensive offloading. Baggage from that car entered the hands of Transportation Guild and Assassins’ Guild waiting outside, agents who worked the port.

From here, everything Geigi brought had a series of procedures and inspections to go through, not so much for mischief—although it was always a concern—as to discover those small thoughtless items like pressurized bottles which might need special containment or outright exclusion.

“I shall visit,” Geigi promised him in leaving. “I shall assuredly visit next year. And I shall give your regards to your on-station staff.”

“I owe a visit up there, before long,” Bren said, thinking of that place, those faithful people. “But as yet I have no date I can plan on. They know the circumstance. Assure them they are in my thoughts. And take care. Take very great care of yourself, Geigi-ji. Good fortune.”

“Baji-naji. Let fortune favor us both, nandi, and new ventures delight us.”

With which Geigi stepped off the train to the platform and Bren went back to his seat at the rear of the car, beyond the galley, with all the baggage suddenly gone, all the car emptied of noise and laughter. He felt a little at loose ends for the moment, a little between,and not knowing how to pick up his routine life—but with a huge sigh for a complex business handled.

Came finally a definitive thump. The baggage door had shut, in the next car. Tano and Algini came back aboard, and their own door shut with a louder thump. Banichi stood by that door, talking to someone absent, likely port security, or the driver of the bus. Jago walked back to the rear of the car where Bren sat, and leaned back against the galley counter.

The train slowly began to roll again.

“Sit down, nadi-ji,” Bren said to her, and in a voice to carry over the sound of the train: “Everyone sit down. We are on our own again. Rest. Take refreshment. You have certainly deserved it. This has been a long several weeks.”

Jago sat down. The rest of his aishid came back down the aisle, collected soft drinks from under the counter, uncapped bottles and sank down on the bench seats nearest—Banichi handed Jago a bottle, and got his own before he settled with a sigh.

His four, his irreplaceable four. It was a relief, as the train gathered speed, to be at last in their company, solo, and to be going home with no crisis ahead of them.

“Our package made it aboard,” he said. It was a question.

“It did, Bren-ji,” Tano said.

“Excellent.” He was a little smug about that item. He had slipped a sizeable and very well-padded case into Geigi’s luggage, one that, under instruction to Geigi’s servants and bodyguard, would not come to Geigi’s attention until Geigi got all the way back to the station. It involved a budding relationship with a really fine porcelain maker in Tanaja, one Copada, whose card he had included with the piece. The artist had expressed the piece up to Shejidan two days ago. Geigi’s own collection was all at Kajiminda, less a few pieces sold off by his fool of a nephew. But one fine piece would now grace Geigi’s station apartment.

They settled for the trip.

But then Algini drew papers from inside his jacket and gave them to him without a word, very flimsy stuff, very closely written.

Jago had said a report would be forthcoming—about the content of the meeting in Tabini’s back rooms. Bren turned on a reading light and paid that report his full attention, while his aishid had their refreshment and waited, all watching him, he was quite aware.

It said, for a header:

Because of the sensitive situation within the aiji’s household and the fact that his aishid is involved, please consider this car insecure for the purposes of this report: we should not discuss these things aloud.

Then: There is reason to consider normally acceptable persons potentially compromised, not by their intention, but by their secondary associations.

Certain individuals, including Tabini-aiji, Lord Dur and his son, Lord Haidiri, Lord Calrunaidi, Baiji late of Kajiminda, and Lord Tatiseigi are all under special protection of Guild known to us, and assigned by the aiji’s seal, at the request of the dowager’s guard, without Guild approval.

Security for Cajeiri is being upgraded as far as immediately practical. The two young Taibeni are being licensed to carry sidearms and to use signaling and tracking systems. Their licenses were being held up, two tests ordered retaken. The aiji himself has ordered them home without the tests, with the equipment. The Guild Council reluctantly issued the licenses without the tests retaken. We do not find this hesitation justified. These young people have seen more action than most licensed Guild of their age.

What went on inside the Guild was information usually restricted. Tightly restricted, as a matter of policy.

Security for you, for the aiji-dowager, and for Tatiseigi and the new lord of the Maschi is being tightened, and we are going over the latter two with particular care. We suspect there may be moves to infiltrate, possibly to get information, possibly to do physical harm.

The following matter was generally discussed between us, the dowager’s aishid, the aiji’s, Lord Geigi’s, and very frankly with Lord Tatiseigi’s guard, who have been cautioned not to speak of the matter even among themselves.

Lord Tatiseigi’s aishid reports that Tatiseigi is revising his own position toward several clans due to the fall from favor of the Ajuri. Tatiseigi’s long feud with Taibeni clan has become detrimental to his security, and he is repositioning himself—cautiously so, because many of his conservative allies have strongly opposed the aiji’s close relationship with the Taibeni and his choosing low-ranking Taibeni bodyguards for himself and his son. This is a delicate matter and Tabini-aiji is asking the lord of Taiben to accept Tatiseigi’s offer without comment or reservation.

We all concur that Lord Ajuri’s breach with the aiji forces Tatiseigi himself to move closer to the aiji’s position regarding the composition of the aiji’s bodyguard. Tatiseigi is therefore committing to the aiji, and leaving safe political territory, his massive influence among the conservatives. Tatiseigi requires support in this, and conspicuous political successes and high favors are being given him in order to maintain his political importance. His physical safety at this time is critical.

That explained certain things. Definitely. Tatiseigi was taking a position that was going to upset the conservatives. And strong signals were going out that the conservatives might get significant concessions from Tabini if they backed off their fuss about Tabini’s relationship with the liberal-leaning Taibeni clan. Ajurihad been a conservative clan, once close to Tatiseigi, then distanced, and now completely beyond the pale. The Kadagidi had been a conservative clan. But ithad backed Murini, and Murini’s excesses had alienated the whole aishidi’tat. The conservatives were not in good shape, since Tabini’s return.

Then he’dbacked off his support for cell phone technology, and upset the Liberals.

And Tabini had urged Tatiseigi, geographically sandwiched between the Ajuri and the Kadagidi, to reach out to his other neighbors, the Taibeni—who were unshakably loyal to Tabini. Welcome to the family, Great-uncle. Ignore our dealings on the tribal bill. We’re backing off on the cell phone bill. We’ve broken the association between the Marid and the Kadagidi, and gotten our own agreement with the Marid. With us, you don’t have to worry about your neighbors.

Damiri—showing up in her uncle’s colors.

He drew a deep breath. And kept reading.

The old alliance of Tatiseigi’s Padi Valley Association with Ajuri’s Northern Association is now broken, at the same time that the Marid under Machigi is reconciling with the aiji, through a private agreement with the dowager . . . in effect trading the north for the south and the West Coast. If Machigi does not keep his agreements, or if political opposition from the Conservatives defeats the Edi bill and frustrates the West Coast, the Western Association will face a worrisome and dangerous situation, with disaffection in the Northern Association, led by Ajuri, and in whatever results in the Marid and Sarini Province should Machigi’s agreement with the dowager fall apart. Therefore passage of the tribal bill is critical and advancement of the trade agreement between the dowager and Machigi is critical.

We have noted that Tabini-aiji, when attack came on him at Taiben and Shejidan, did not first resort to Ajuri or to Atageini, though Damiri-daja was with him, and related to both. He believed that his going to either for help would make them a target—and neither is noted for strength in arms.

When we all, the heir, and the aiji-dowager returned from space, it was the aiji-dowager’s natural choice, through geographical position, to resort first to her husband’s associates, the Taibeni, then to her own longtime associate Lord Tatiseigi. This gave Tabini-aiji no choice in where he must first make an appearance. His return to power began on Lord Tatiseigi’s land, and by virtue of that, Lord Tatiseigi became the aiji’s first and foremost supporter in his return to power, joined by the Taibeni, and rapidly by many smaller central and coastal clans who had had their district authorities suppressed and replaced by outsiders in favor with Murini. The popular movement gathered force.

At that point the Ajuri lord arrived, and began to promote the Ajuri connection to Damiri-daja.

The Ajuri lord died under questionable circumstances. Lady Damiri’s father Komaji took the lordship of Ajuri. Komaji had an excellent chance to have mended his personal feud with Tatiseigi, and chose instead to exercise it. Simultaneously he pressed his relationship with Lady Damiri and spoke detrimentally about human influence on the heir, and about the dowager’s teaching, while he was in the dowager’s care. His presumption on his relationship with Damiri-daja culminated the night of the dowager’s agreement with Machigi in an attempt to gain access to the aiji’s apartment, which greatly alarmed the heir’s young bodyguards.

He is now barred from the Bujavid and the capital, though he has not been forbidden communication. He has set himself in an untenable situation. We do not credit him with good judgment, and the heir’s insistence on bringing human associates down for his ninth and fortunate birthday celebration is likely to light a fuse, where Komaji’s resentment is concerned. If anything were to happen to the heir, Damiri’s second child, soon to be born, will become the heir instead—without the dowager’s influence, and without human influence.

In general principle, conservatives would greatly prefer this. Komaji would be that child’s grandfather, and his jealousy of Lord Tatiseigi suggests several moves that would work to his extreme advantage: assassinating the heir, and/or Tatiseigi—provided the event could be sufficiently distanced from Komaji.

We have suspicions regarding the death of the former lord of Ajuri. We wonder what other clans might have wanted the silence of the grave over their dealings in the Murini era. We have directly asked Tabini why he avoided Ajuri during his exile, and he confirmed he had his own suspicions of that clan, but did not voice them to Damiri. We suspect the former Ajuri lord’s own bodyguard conducted that assassination, and subsequently removed records of Ajuri dealings during those years—records that might have proved theft and assassination—even within the clan and the subclans. Komaji is regarded within his own clan as a man who allows emotion to guide his actions. He is not respected, but he is feared. His relatives may not tolerate him much longer, but we cannot rely on that situation to protect the heir.

We have strongly suggested to Tabini that a Filing would assist us.

Return this note now. We shall destroy it.

Bren handed it over. Algini touched it with a pocket candle-lighter and it went up in a puff of flame, leaving only a fluff of gray ash that fell apart.

“I understand,” he said.

Tabini didn’t want Damiri to take over Ajuri. He didn’t want her to have any part of it.

Why? Because, Tabini had said, Ajuri swallowsvirtue.

And he had said that Damiri couldn’t settle on a clan. Even when she was wearing Tatiseigi’s colors, and bearing a Ragi child.

Problem, Bren thought.

Problem, of a sort a human was very ill-equipped to feel his way through. Damiri was not a follower, but a leader—of a strong disposition to wield power. That disposition had made her valuable to Tabini. She had a quick mind, an ally who understood him to the core; but in the way of atevi leaders—it made an unruly sort of relationship, a unison of purpose very, very difficult to keep.

Interpret Damiri’s actions as emotion-fueled and self-destructive?

He didn’t think so. Not even considering her condition. She might have shaky moments, but that brain was working on something. And she had a father she was not that close to, who was nowhere near Damiri’s level, not in intelligence and not in leadership qualities.

No. Damiri was no fool. She would do exactlywhat she considered in her own interest. Tabini would do exactlywhat he considered in his—which included, above all else, the survival of the one association that kept the atevi world peaceful and prosperous: the aishidi’tat.

The dowager’s ambitions were much the same. The dowager had helped createthe aishidi’tat. She had created the last aiji; she had created Tabini; andshe had taught Cajeiri.

What did Damiri fight for? What was herdriving interest?

It was disturbing that she opposed the dowager . . . and that he had no real answer for that question.

7

Cajeiri, at his homework, because he had nothing else to do, heard the front door open, out in the foyer beyond the hall. That was an ordinary thing. Servants came and went all the time.

Then he heard a familiar young voice out there, and another, and with that, he was out of his chair, out the door of his own suite and down the short hall as fast as he could run.

“Nadiin-ji!” he exclaimed. Indeed, in the foyer he saw not just two, but all fourof his bodyguards.

In uniform. All of them. Antaro and Jegari, had traded the greens and browns of their clan, and went black-uniformed, black-ribboned, and armed. They carried pistols in holster, just like the other half of the team, Veijico and Lucasi; and just like any Guild anywhere.

Now—they were realbodyguards.

“Nandi,” Jegari said with a proper little bow, while Seidi, the major domo, stood in the background.

“Are you to stay here now?” he asked, hoping that was the case. And: “You look tired.”

“They are not entirely through the first level,” Lucasi said—Lucasi and Veijico, also brother and sister, like Antaro and Jegari, were years older; but it was Antaro and Jegari who ranked seniors, having been his since he came back to the world, even if they were only apprentices. “There are tests yet to pass, nandi, but we are all back to stay. The rest we can do in stages. From here on—they are no longer apprentices, and we shall race each other up the levels.”

“We shall be sending in the written course work,” Veijico added. “We have a special dispensation, both to test outside the Guild headquarters, and for us to administer the tests. Your father ordered that. We shall be spending time in the Bujavid gym, in hours when you have your father’s aishid on premises, and on the firing range, the same. But otherwise we are intended to stay on premises, nandi. So we shall not leave you again.”

“Well, one is very glad!” Cajeiri said. “Come in, come in!”

He was used to Veijico and Lucasi having guns. There was a special locker in each of their two rooms, where those and other equipment stayed. But he was not used to Antaro and Jegari’s new appearance. He was used to them in ordinary clothing, like him, or lounging about in a variety of tee-shirts and casuals when they were entirely alone in the evening. Seeing them as somebody he had to obey instead of ordering—that was a little different thing, though he could not think of anyone better for him. They both seemed to have grown overnight, to have gotten bigger, and taller, and actually dangerous-looking. Like many Taibeni, they had a look, a little sharpness of face, that made a frown quite convincing.

Now everybody had to realize they had authority. That was the point of it all.

Now when they told somebody to move aside, they had better move and not argue.

It also meant Lucasi and Veijico had real partners to back them up in case of trouble, and the four of them all together meant he had a real aishid, who would be with him all his life, more permanent than any marriage. How important that was, he had come to understand in the way Great-grandmother’s aishid and nand’ Bren’s aishid operated—and how his father’s aishid was desperately trying to operate, except they were all young.

Trust? He had always had that for Antaro and Jegari, from the day they had met. Lucasi and Veijico were much newer in the house, and they had made a bad start, when they had thought they were above belonging to a child. But after they had acted out and gotten people hurt, and after Great-grandmother’s and nand’ Bren’s bodyguards had had their say, Lucasi and Veijico had come back with a deeply changed attitude and begged to stay.

And he’d known, then, that they meant it. Just . . . known, somehow, at the bottom of his stomach. From that time on, trust had happened, which was very important. Best of all, they were reallygood, and they knew interesting things, and they were perfectly accepting of Antaro and Jegari now, saying that they were no fools, that their skills had been very high to start with, and that after a few years, being five years older or younger would not be that much, anyway.

“We have yet to get our briefing from your father’s guard,” Veijico said.

“Go,” he said, “And then tell me what you find out, nadiin-ji! No one ever tells me anything. There was a party last night, and a big Guild meeting about something. I think my grandfather is making trouble, and I want to know. It is importantthat I know. I have things also to tell you!”

They had set down their baggage by the door of his suite. It was black leather bags, the same sort that all Guild carried and not for anyone else to touch. “We shall take this to our rooms,” Antaro said, and they did.

Then they went out again, on their grown-up business.

He was too excited now to go back to his homework—not knowing quite what to do with himself until they got back, and hoping more than anything that their having passed the tests might let him go places again—like to the library to pick out his own books, and maybe to visit mani and nand’ Bren.

His birthday was coming; his guests were going to come; and now that his entire bodyguard had qualified to carry weapons, at least no one could turn up at the last moment saying he did not have professional guards.

“When we all come back,”Veijico had said to him privately, the day they had gone to the Guild, “when we come back, Jeri-ji, we will be a whole aishid. We will be a weapon in your hands—a real one. You will have to be very careful what you ask us to do, because wewill do what you ask us to.”

That was the scariest thing anybody had ever said to him—scarier even than anything mani had said. He thought of that, standing alone in his sitting room, with heavy weapons probably in those bags. He could tell them to kill somebody.

And they would.

And maybe get shot doing it.

Maybe die.

Boji chittered at him from his cage, diverting him into the real moment. Boji rattled the cage door, and reached fingers through the convolute metal flowers of the cage.

He felt a lot like Boji. Locked in. Kept.

And all of a sudden he felt that he was getting a lot more cautious than he had used to be. A lot smarter. A lot more aware what could happen in the world. He was not sure he liked the changes the year was making in him. He was not sure he liked it at all.

I could not steal away downstairs today and catch the train, could I? I did that when it was just Jegari and Antaro and me—we three could do that.

But now Lucasi and Veijico would get in trouble. Now everyone is Guild, and we cannot go back, can we? We cannot sneak out and catch the train, we cannot even sneak down to the library—not because I would get in trouble, but becausethey would get in trouble.

And they would do it, if I asked.

But I cannot ask them. Can I?

Damn it.

He was caught. He did not want to grow up. Not yet. He wanted to be a boy. He wanted to slip away the way they had on the starship, and go places where he could still play games.

But there were no places like that on this floor. And any otherfloor of the Bujavid was not safe.

The world had gotten serious and stayed that way. His guests were going to say, “Come on, Jeri, let’s go . . .”

And he’d have to say no, it probably wasn’t safe . . .

Because his stupid grandfather had made things worse just when they could have really gotten better.

Maybe,he thought, I can think of something.

And: I can still get my way. I just have to be smarter about it.

My associates are coming down here. I have to be good until then. I have to follow all the rules and do my homework and be so good even my mother will be happy.

And once my guests get here, then there has to be something to show them when they come. They have never seen the ocean. They have never seen trees and grass. They have never seen a sunrise. I had to describe it all for them.

I have to show them everything. I have to show them the best things, so we have something to talk about, and they will want to come back.

I would like them to come back. I would like them to be here when I grow up. I would like to have people like nand’ Bren, who have no clan, and owe nothing to anybody else. Just to me.