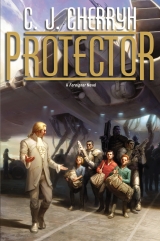

Текст книги "Protector "

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 25 страниц)

“Don’t do that,” Gene said. “If you look, you’re just going to be worried about it. And you know what they said. Whatever it is, just eat it. They’ll be sure it’s safe for us.” He had eaten his egg in two mouthfuls, washed it down with fruit juice, and took a bite of the sandwich. “Pretty good actually, together.”

“I hatespicy things,” Irene said in a thin voice.

“You’re going to get real hungry in two weeks,” Artur said. “Better eat it, girl. You know what the captain said.”

Irene did, squeezing her eyes tight shut. She ate it like Gene, in two big bites, washed it down with sweet orangelle, which was, truthfully, not the best combination, but that was the drink she had wanted. She shivered all over. “It’s sour!”

“Won’t kill you,” Gene said. “Got to do it. Or in two weeks you’re going to be a lot skinnier.”

“Long time ’til supper,” Artur said.

“Try the teacake, Rene-ji,” Cajeiri said. Everybody liked cakes.

She was upset. Irene got upset when they teased her. But after a little bite of that, her face brightened. “Oh, that’s good!”

“Dessert,” Gene said. “It’ll be a good last bite.”

“Come on, Reny,” Artur said. “Dareyou. You can do it. You’re not going to back out now.”

She had another bite of sandwich.

The lunches all disappeared—in Irene’s case, in large bites, quickly swallowed, washed down with the fruit drink. It was, Cajeiri thought, fairly brave of her, especially the egg, which, to be honest, he had used to dislike. He gave her his own teacake, and she looked at him.

And very reluctantly pushed it back, as his.

“I can get more,” he said, which was almost always true. If they were there for dessert, there would be a supply for tea. “Do you want more?”

They did. He asked mani’s guards if there were extra cakes, and indeed, they each had one more, to finish their lunch, and then black tea, which Irene also found a challenge, but she drank it.

“Ugh,” she said after a big mouthful, but after a moment she took another one. And another.

He had used to bring food from mani’s table to the passages of the ship, so it was not their first sample of atevi cooking, but it was a lot more elaborate. He had been afraid what he brought would poison them, before, so he had mostly stolen sweet dried things they thought were candy.

Now they had to face slimy pickled eggs. But they liked the cakes, and they had eaten all of a whole regular meal, and nobody was sick.

That was verygood.

After they had cleared away lunch, they sat at their table and talked and talked—about living on the station, and where they lived now, and what they had been doing for the last year—Irene and Artur had lessons, mostly, a lot of math and science. Their parents were strict about it. “We couldn’t get out much,” Irene said. “The station’s big.” She used several words he could not get, saying something about Mospheirans that sounded unhappy.

“The atevi section you can’t get into,” Gene said. “I tried. I just wanted to see, you know. Security is pretty tight. That was a bigmistake.”

His face wasn’t happy when he talked about that. The others looked uncomfortable. Everything they said about the station sounded unhappy, but he could only get the little words, not the big ones.

He tried to think of something else in the awkward silence, something that would make them happy. Something they could talk about. Then he thought about his slingshota. He took it out of his pocket, and took out the three stones and laid them on the table.

“What’s that?” Gene asked.

“One of my good things.”

“That’s weird,” Irene said, and reached out carefully and fingered the handle very carefully. Tapped it. “Is that plastic?”

He didn’t couldn’t remember their word for wood. “Tree,” he said. “Tree stuff.”

“You’re kidding,” Gene said. “Wood?” He touched it carefully. “I’ve never felt it.”

Artur picked up one of the stones, and said a new word. Irene said it again and added: “What planets and moons are made of.”

“Rock,” Cajeiri said in Ragi. “That’s a rock.”

“Rock,” Artur said. “Rock, yes. I guess it is. But I’ve never had my hands on one.”

“You’re kidding,” Cajeiri said, and then he remembered they had never been outside the ship or the station. And he could not think of anywhere on the station that was rock, or stone.

“It’s smooth,” Artur said, then, and he rolled it around between his fingers. “Is it made?”

“Water,” Cajeiri said. “Water made it smooth.”

“How,” Gene asked, “do you make it do that?”

That was an odd question. But then he realized he had no ship-speak word for river. Or stream. There was ocean. But no word for waves or beach. What they had talked about on the ship was the ship, usually. Occasionally stories they remembered.

He had come prepared. He had a little notebook, and a pen. He started drawing the seacoast, and the peninsula. “Najida. This. Nand’ Bren’s.” He started describing things in Ragi, slowly, and Irene wanted paper, and borrowed the pen to write the words her way on her paper. So they started giving each other words, using the rocks and the slingshota and the juice sloshing in the cup. Waves. Beach. Rocks. Pebbles. Sand. Tides.

It was the old game, the way they had used to be, and he began to feel increasingly at ease. He showed them how the slingshota worked, and that got the attention of mani’s bodyguards—but he did not fire a stone, no. He just showed them.

“That’s really wicked!” Gene said, admiring it.

“Neat,” Artur said.

They were impressed. And everything was perfect.

• • •

The young group back there, Jago reported, and Kaplan also observed, was entertaining themselves very happily, and being remarkably quiet about it. Bren and Jase sat and talked, and Ilisidi and Tatiseigi conversed at length, before Ilisidi invited them to sit together and do small talk regarding the ship, the persons Ilisidi dealt with—notably Captain Sabin.

“We are trying to persuade Lord Tatiseigi to pay a visit to the station,” Ilisidi said lightly. “Perhaps you can prevail.”

“One would realize the extreme honor of such an invitation,” Tatiseigi said with a forbidding gesture. “But I would decline. Flying does not agree with me.”

“There is no such sensation on the space station,” Ilisidi said.

“One has no desire to be sealed into a tube and flung into the heavens. With all courtesy, nandi,” Lord Tatiseigi added, with a little nod toward Jase, “toward the elegance I am told exists in the heavens. I am certain it exceeds imagination. But simply to move between Shejidan and Tirnamardi is such an untidy business. One can only imagine the difficulties of a household lifted to the station. Yet—yet I am aware both you and nand’ Bren do maintain such arrangements.”

“We have very capable staff, nandi. Extraordinary people.”

“Ah. There is the grade,” Tatiseigi said relative to the train’s motion. It was slowed a bit, then gathered speed again. “That will be a quarter of an hour to our destination, nandiin. Not so rapid as your shuttle. But one is accustomed to it.”

Guild around them were getting up from seats, putting away service items.

“Nandiin,” Ilisidi said purposefully, then, in a tone that had nothing of banter about it. “We shall enjoy the hospitality of our esteemed Tatiseigi. We shall see nothing untoward comes near these children.”

“Let me assure the ship-aiji,” Tatiseigi said, “that he is welcome under my roof. We have ample room. Ample room.”

“Nand’ Tatiseigi.” Jase gave a very courteous bow, with no hint of bemusement—though he was amazed, Bren was sure. The old man had been pleasant the entire trip. Happy in the event? Bren wondered.

The old man was going to get off the train and run into Taibeni, who were coming in, arranged by Tatiseigi’s own staff. He thought a warning might be in order. He decided on it.

“There will be, one is advised, nandi, Taibeniat the station. An assistance. They are reliable.”

A brow quirked, just a little. The iron good will stayed in place. “Our allies,” he said, as if the words tasted entirely strange. “Yes. That is good to know, nand’ paidhi.”

12

The train pulled to a stop. The door opened. The dowager’s men went out first onto the platform. The word came back, clearly, and more went out, and the baggage cars next door opened up, distant thumps.

Bren got up. Jase did, then Lord Tatiseigi, and, last, Ilisidi, as the aisle had mostly cleared and unloading was proceeding outside. The youngsters stayed where they were—courtesy of the youngest Guild present. Kaplan and Polano, who had generally tried not to block the aisle, and who had found the far side of the galley the easiest for their bulky stance, put their helmets on, as Jase slipped a communications earpiece into his ear and from that moment on was in communication with them.

“Let Cajeiri’s aishid move the kids,” Bren said. Maneuvering was too tight for Kaplan and Polano, and Cajeiri’s aishid was getting instructions. “Bren-ji,” Banichi said, his own signal, and he joined Banichi and Jago, going quickly down the aisle, in a fast sequence. Jase and his guard would be behind them. Tano and Algini were near the door. Guild moved their own baggage. Personal baggage stayed—it would get there, but not on the bus.

The open door brought a bracing waft of valley air, and daylight, a step down to the platform—baggage was piling up, and a cluster of Taibeni in brown and green were handing it out, one to another.

Bren followed Banichi’s gesture, left turn, moving with dispatch; the kids all together, with their young escorts, all headed toward the vehicles waiting beside the platform, in front of a small stand of trees: the red and black bus up from Najida, and two old and well-used green and brown trucks. Taibeni colors, those, checked and secure.

The human kids stopped abruptly—frozen in place, staring . . . as three riders on mecheiti moved past the bus. Lean, towering beasts, mecheiti were built for speed, twice a human’s height, with curved necks and shining brass war-caps on the short tusks that jutted from the lower jaw.

Stopping was prudent. The mecheiti had caught wind of something foreign, and the lead rider used his quirt to move his mecheita past, giving their group a wide berth. The other two followed, around the station office, out of sight.

Welcome to the Padi Valley, Bren thought, as he followed Banichi down the steps of the train station platform.

The kids were close behind, Cajeiri and Gene in the lead, then Artur. Irene was coming, holding to the wooden rail and looking anxiously in the direction the riders had come from. Veijico and Lucasi were right with her, wanting her to catch up, and she jogged a couple of steps, the kids bunching up again.

Off to the right was another group of riders. It was the trucks that were the rarity in Taiben. The lodge had them, for supply, for commerce; but the forest that was Taiben, the deep woods—mecheiti navigated those narrow trails and crossed the hunting ranges efficiently, with no need for costly and intrusive roads. It was a way of life far different than other clans—the Taibeni-Atageini war had lasted over two hundred years for one thing because the Taibeni had never cared much what their neighbors did, or thought. The Taibeni used the same train station as the Atageini. They had visitors come in, and they would get them and their baggage to the lodge deep in the woods, by the sole road.

For the rest—Taibeni sons and daughters took service in certain of the outside guilds, and there was indeed a lord of Taiben, but he rarely went to Shejidan unless a vote was close. They had had occasional disputes with the Atageini, usually around this train station—but nothing like an active war.

Bren reached the bus, where Taibeni riflemen stood—hesitated there to look back at Jase. “Best we board last,” he said, and waited there while the last of their party came at their necessary pace. The train, meanwhile, continued to produce baggage that young Taibeni passed off the platform and onto the truck.

There was one large, unlikely item that came out of the baggage car. With Cajeiri’s servants.

He was aware of Jegari, observing from the steps behind him. “Nandiin,” Jegari said, and vanished up onto the bus. “They have it,” Bren heard him say, inside. “It is coming, nandi.”

A shriek rose above the platform. Boji was excited.

“A pet,” Bren said to Jase, watching Tatiseigi exchanging a word with one of the older Taibeni. It was a remarkable moment, lost in the rumbling of the huge cage as it came closer to the platform edge. They were going to have to take that down the ramp and lift it in.

“They’re moving fast,” Jase remarked in ship-speak. “Are we worried?”

“The Taibeni want this part to go right. The dowager’s involved. Tatiseigi’s a new ally. And they don’twant to linger here. Technically the rail stations are neutral ground. They want to get back into defined clan territory—which in this case is Tatiseigi’s. There, what happens is Atageini responsibility.”

Ilisidi and Tatiseigi were headed for the bus now.

“Your lads are going to have to do what they did at the port,” Bren said. “Board last.”

“No worry,” Jase said.

Nawari and Casimi were with Ilisidi, help enough on the steps, and she had her cane. Tatiseigi had two of his bodyguard. Bren reached for the assisting rail, and Jago gave him a helpful shove from below. Jase came up, likely the same way; Jago and Banichi, Tano and Algini all boarded and went past them, toward the rear.

Bren sat down in the seat facing Tatiseigi; Jase sat down across from Ilisidi; and the children were in seats across the aisle. Kaplan and Polano boarded, and the driver shut the door.

“Well,” Tatiseigi said. Tatiseigi was to ride a pleasantly warm bus instead of his own antique and elegant open car, but not necessarily happy about it. The kids exclaimed and recoiled from the window, as the heads of mecheiti appeared, the riders passing right beside the bus as it began to move. The kids’ outcry, not the mecheiti, got a twitch from Veijico; but they were all right. Cajeiri was laughing.

“One noted Ragi colors on this conveyance,” Tatiseigi said. “Indeed, thosecolors are always welcome on Atageini land.”

Bren was not about to admit it was his personal bus. No. It was going to come out. He had to say something eventually. Just—not at this moment.

Cajeiri was happily pointing at something. The children leaned to look. Bren had no idea what they were looking at. The back aisle was packed, Guild seated where they could, standing where they could find room. But not enough of them. A few of Ilisidi’s young men, Bren thought, must be staying with the two trucks.

The driver took a right turn, up and over the track, and onto the road.

The packed crowd swayed. Steadied. Trees whipped past, close at hand, which had used to affect Jase. But Jase seemed perfectly steady despite the movement, the horizon problem. He even turned to have a look out the other side.

“Are you all right?” Bren asked Jase, in ship-speak. “Medication holding up?”

Jase put a hand on his forearm. “Constant dose,” Jase said. And changed to Ragi. “One is faring very well, Bren-ji. One needs to settle in, now. One must get the vocabulary up.”

It took only a few minutes of conversation—mutual acquaintances, the cell phone affair, the changes in the apartment and the problems getting the Farai shifted out of his residence before they could even think about reconstruction—before Jase was “settled in.” Jase glitched on the occasional words, but he’d been working. And he kept a fortunate numerology on the fly; it was no small trick.

The bus reached rolling grassland, open, a relatively unlikely spot for snipers.

Thank God, Bren thought.

They had reached Atageini land, and done it without incident.

• • •

The road became a grassy track through the hunting range, and straight as an arrow. The mecheiti riders kept up with the bus quite handily, the bus taking only a moderate pace.

And there was, scarcely visible except at the very edge of the track, a peculiar condition on the road. The only vehicles that routinely took this track were Tatiseigi’s magnificent open car—rarely—the estate truck, traveling either to the train station or to the town some distance to the northeast, or town trucks and vans, taking people to the train station, or bringing supplies into the estate. As roads in the Padi Valley went, it was a veritable highway—

But usually the grass stood up.

At the moment, as best Bren could observe from his vantage, the grass was quite flattened. The road was well-defined, indicating a lotof recent traffic. Bren glanced at Tatiseigi, wondering if the old man had noticed that, and noted how much traffic, most of it perhaps from Taiben, had gone to and from his land.

Tatiseigi, however, was busy talking to Ilisidi.

One had an idea that Guild on the bus, standing in the aisle back there, hadn’t missed it. But they probably had no doubt of the cause. Trucks had been moving in equipment and supplies, setting up what Cenedi had arranged.

They took a slow curving turn.

“I see the hedge!” Cajeiri exclaimed, from his side of the aisle.

The estate hedge, indeed it was, a thick green barrier that towered up as high as a two-story building and went on and on over the horizon, defining Tatiseigi’s personal grounds. It was thorny stuff. It had grown around massive stakes, from ancient times, when mecheiti riders, cannon, and muzzle loaders had contended in district wars. Absent the cannon and modern artillery, it was stillformidable, tough and fibrous strands with thorns the width of a man’s hand, and as thick as the bus was wide—a barrier even mecheiti would not attempt.

The whole perimeter had only a formal front gate, which came visible just ahead, and a smaller, more utilitarian one on the far side of the house.

The bus slowed to a crawl, then almost immediately rolled forward as the ornate iron gates opened electronically, the riders going ahead of them.

Taibeni, moving freely into the heart of Atageini land.

“Home,” Tatiseigi said, sitting with his back to the movement of those riders.

They rolled onto gravel, now. The inner road was well-kept, running beside the southern hedge, rimming a broad, rolling meadowland, a huge expanse of it. Lord Tatiseigi’s grounds were famous and extensive, enclosing pasturage for his mecheiti herd and providing insulation from the world.

But something elseshowed, from Bren’s view: a cluster of trucks, one with a mast and communication dishes, and a handful of tents. The mecheita riders headed off in that direction, toward what had to be a Guild field camp.

His fixed stare had gotten Tatiseigi’s attention. Tatiseigi turned and took a look out the window, straight out, then further over his shoulder as the bus moved past the camp.

“There is a campon my grounds!”

“There are two small camps, Tati-ji,” Ilisidi said. “You know we are taking measures. They will be out of sight, quite out of the way. You will not know they are here.”

“Aiji-ma,” Tatiseigi said, visibly perturbed. “All this business of new men and retiring my old servants—and taking one of my storerooms—I have resigned myself to new faces; but I am beyond uneasy to be met with this campat the gate. How much more is there, up at the house?”

Ilisidi held up a finger. “One little antenna on the roof. A camera or two. You will not see them from the ground.”

“Aiji-ma,” Tatiseigi said, and Bren decided it was a good time to study something off to the side and across the aisle.

“Is the threat that great, aiji-ma?” Tatiseigi asked.

“Tati-ji,” Ilisidi said, “our conscience still troubles us, after the damage our presence inflicted this last year. You have been so staunch an ally—well, I shall say it: brave.You have been the bravest, the steadiest, the most trusted and the closest of our allies. I lie awake at night thinking of the danger, not so much to me– Ihave such very extensive protections constantly about me, and I have come through every attempt. But, Tati-ji, my closest associates are, by comparison, far easier targets, and the very ones my enemies will go after first, to do me harm. They know they cannot attack me—until they have buried my allies, my protectors, and taken away my strongest supporters. Terror is their weapon, and I know youdo not feel it—nor do I—but let us not give them access here. These are an enemy that has no respect for such ancient premises. These are people who attack civilians and servants, and have not observed any such requirement as Filing. This enemy murders old servants, like gentle old Eidi, who died at my grandson’s door, brave, loyal and holding his post. I cannot suffer such losses. I will not have such things happen here. I will not have a single vaseshaken on a shelf in Tirnamardi, let alone these bloody-booted outlaws tramping through your halls, destroying what they are too crass ever to understand. No. I need you, Tati-ji. I shall not have your bravery putting you at risk! I will not lose you! Suffer these small changes. And stand by me.”

My God, Bren thought. She had the gift.

“Aiji-ma,” Tatiseigi said. “One hears. One is honored by your concern.”

The bus rolled on.

Jase said, quietly, “This is all your estate, Lord Tatiseigi? It is huge. I have tried to think how long it took this hedge to grow.”

Tatiseigi, still unhappy, said past a clenched jaw, “Four centuries, ship-aiji.”

“It is very beautiful, this place,” Jase said. “I am very grateful that you have offered your hospitality. I shall try to be a good guest.”

“Honored, ship-aiji.” Tatiseigi gave a nod of his head, unbending a little, though he kept looking anxiously out the window, in search of other tents, one could well imagine. “You hosted the aiji-dowager aboard your ship. One is pleased to return the gesture, in her name.”

“Nandi,” Jase said properly, with a little nod.

“Those two—” Tatiseigi said, resigning his search for tents with a little shift of the eyes toward the aisle, by implication Kaplan and Polano. “Is that their indooruniform?”

“No, nandi,” Jase said. “Not at all. They wear it now because I am traveling between safe places, but once indoors, be assured, they will be happy to put on ordinary clothes.”

“Indeed,” Tatiseigi said diplomatically, nodded, and looked measurably relieved.

The bus rolled on at a moderate pace on the graveled drive, and exclamations from the youngsters said they had seen something.

Bren looked ahead, between Ilisidi’s seatback and Polano’s white shoulder.

The last time he had seen Tirnamardi, there had been shell-holes in the masonry and broken gaps in the low, ornamental hedge of the front drive.

It sat on its low rise looking as serene as if there had never been an attack from the Kadagidi. The road curved. The grass had grown over the trampled lawn, and, on the other side of the bus, the house, a rectangular stone affair of many windows, showed neither patches nor scaffolding.

“I can see the house, nandiin-ji,” Bren said, “and it is beautiful again, nandi. Absolutely beautiful.”

“Well, well,” Tatiseigi said, “it has been a struggle.” He drew a deep breath, and courteously addressed himself to Jase. “Understand, ship-aiji, our neighbors attacked us with mortars, and even our allies made wreckage of our hedges. We sought out shrubs of exact girth and age, and we have nurtured them through last summer. We have brought stone from the exact quarries, and while the match is not perfect, it will age.”

“We look forward to it,” the dowager said, as the tires rolled onto the paved part of the drive, rumbling on the brickwork. On that broad curve, the bus slowly came to a halt. The doors of the great house opened, pouring out servants and Tatiseigi’s security.

The bus door opened. Kaplan and Polano had to be the first off. One hoped security was warned.

“Now you must escort us, nandi,” the dowager said, setting her cane before her, and Tatiseigi gallantly struggled to his feet and offered his hand.

Guild had sorted themselves out by the seating arrangement of their lords, and Cenedi and his group moved out, immensely relieving the congestion back there, and Tatiseigi’s aishid after them. Cajeiri got up, and his guests did, as Bren and Jase got up.

Banichi and the rest of the aishid followed right behind them. They stepped down the far last step onto the pavings of Tatiseigi’s drive, with Kaplan and Polano waiting at the left, the dowager and Tatiseigi already headed up the steps. The two trucks with the baggage were right behind them. The white dust of the gravel was still lingering in the air along the road.

The children came down next, exclaiming in amazement at everything.

“They’ve never seen a stone building,” Jase said quietly. “Or a building, for that matter. Everything’s a wonder to them. They’ll want to know everything.”

“It’s supposed to rain tonight,” Bren said. “A few showers. That should provide entertainment. So much of the world one takes for granted. We haveto arrange that fishing trip, Jase.”

“I’m going to do my damnedest,” Jase said. “So many textures. So many details.”

They walked up into the foyer, the hall of lilies, those beautiful porcelain bas relief tiles that were the pride of the house, and there was Tatiseigi, Cajeiri, and the dowager watching three human children standing in awe of the porcelain flowers.

“They’re cold,” Artur said, touching a flower petal with the merest tip of his finger. “But not really cold.”

Then they all had to touch, very gently.

“Ceramic,” Bren said. “Bow nicely to your host and tell him you think the flowers are beautiful.”

They did exactly that, and for the old lord, clearly anxious for the welfare of his lilies, they could not have picked a better feature to compliment. He nodded benignly.

“They are very delicious,nandi!” Artur insisted, as if Tatiseigi had failed to hear the compliment, and Cajeiri quickly snagged his arm and Gene’s and, Irene following, got them all up the steps and into the main house ahead of the adults.

“Wow!”echoed upstairs, as the youngsters got a look at the halls inside, the ornate scrollwork, the lily motif repeated, the grand hall with its gilt, the high windows, the paintings and vases.

Bren said, quietly, “One believes the boy’s attempted word just now was beautiful,nandi. The children are absolutely in awe of the house.” Indeed the old lord had just had his precedence and the dowager’s violated, in his own front hall. “One sincerely apologizes.”

“For my great-grandson,” Ilisidi finished dourly, though Bren thought the young gentleman had been admirably quick about getting Artur upstairs before he mispronounced beautifulagain. Ilisidi made the climb to the main floor on Lord Tatiseigi’s arm, as the high hall echoed to young voices. The children were standing in the center of the hall, revolving like so many planets as they gazed all about the baroquerie and the gilt stairway and the windows.

“Lord Tatiseigi is bearing up with extraordinary patience,” Bren muttered to Jase as they walked up together, his aishid walking quietly, and Jase’s pair with servos whining at every step.

“Beautiful!”was the word from above. Safely in ship-speak, this time.

They reached the main floor to effect a rescue.

But, unprecedented sight, the old man stood beside Ilisidi with a smile dawning on his face, watching the children so admiring his house. She smiled, pleased as well. “Well, well,” he said. “They are certainly appreciative.”

Cajeiri saw them, cast a worried look at his guests, and hurried over to give a sober, harried bow. “Mani, Great-uncle! Shall we be lodged together? May I take them upstairs?”

“As the dowager permits,” Lord Tatiseigi said, and nodded toward the handful of servants lined up by the stairs. “They will guide you. Do tell the servants, young gentleman, they should open the white suite for Jase-aiji and his bodyguard. —Ship-aiji, my staff will make suitable arrangements, and if there is any need, do ask my staff. —Nand’ paidhi. You will have the blue suite. I am confident it is ready for you.”

“Nandi,” Bren said with a little bow, and to Jase—not sure Jase would have understood, since when he spoke to his own, Tatiseigi used the regional accent: “The white suite is adjacent to the blue. We’ll have time to catch up before—”

About that time there was a sudden bang and a considerable clatter and sound of wheels on the marble floor downstairs.

Lord Tatiseigi looked alarmed.

A shriek echoed up from the foyer, ear-piercing and echoing.

The human kids froze in alarm. Ilisidi simply said, with a sigh, “The parid’ja, Tati-ji.”

Tatiseigi drew a large breath and said, “There are no antiquities in the suite assigned to the young gentleman and his guests.” He signaled and snapped his fingers for staff, who stood looking downstairs. “The young gentleman’s suite, for that.”

No breakables seemed an excellent idea, in Bren’s opinion. He had no idea how they were to get the cage upstairs but to carry it. There were no lifts in Tirnamardi, most features of which predated the steam engine.

But they were safe. They were within walls, inside a security envelope that three clans, the paidhi’s security, and ship security were not going to let be cracked. He had worried all the way. But what Cenedi had had moved in here was not just the presence of younger Guildsmen, and more of them, it was surveillance. And, he was sure, it was also armament to back it up. Nothing was going to move on the grounds without their knowing.

And count the mecheiti in that camp as a surveillance device right along with the electronics. Surveillance andarmament: one did not want to be a stranger afoot with mecheiti on the hunt.

• • •

Uncle’s house was just the way Cajeiri remembered it—only without the shells going off outside—and his birthday was absolutely certain now. Uncle had been patient, mani was not unhappy, Jase-aiji was a happy surprise for nand’ Bren and for him, too, and it was what he had dreamed of, having Gene and Artur and Irene with him.

They all trooped along with the servants who guided them up the main stairs, and by the time they got up to that floor, there, making a huge racket, and silhouetted in the light of the windows at the end, came Boji’s cage, and his servants, Eisi and Lieidi, and two of Uncle’s, pushing it up the hall. Boji was bounding around, terrified by all the rattling and the strange place and the strange people, after the train ride and the truck, and he let out shrieks as they came, right to the middle suite on the floor, while he and his guests waited.