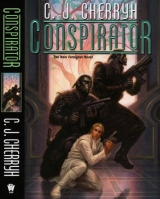

Текст книги "Conspirator"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

“And shall we sleep underwater, nandi?” Cajeiri asked.

Bren nodded agreement. “You may, if you choose, young lord.” His own boat had sleeping only for nine, and that was going to be room enough to put the youngsters below: but somebody was going to have to sleep on deck, if Barb and Toby came along, as he expected them to do. Problems, and possibly they should use Toby’s boat, which accommodated a larger number. But the problems were small ones, and he had promised Cajeiri hisboat, now that Cajeiri had made the crossing of the straits on Toby’s boat—one learned, with the heir, that such details in a promise were a gate through which a whole mecheita could be ridden, sooner or later.

They came down the hill toward the drive, and swept up to the front door, which was a paved stretch. Barb and Toby came out with the staff to meet them, and as Bren got off the bus with Jago and Banichi right in front of him, the young rascal clattered down the steps after him, waved an arm and shouted out, “Hi, Toby! Hi, Barb!”

It was not Toby and Barb that Cajeiri shocked. Ramaso looked completely set aback, others of the staff looked from one side to the other, as Toby called out, in Mosphei’, “Hello there! How was your trip?”

“Pretty good,” Cajeiri said in a ship-speak accent and let Toby clap hands on his arms. “This time we rode in a car with canned food.”

Last time had been iced fish. That was true. Bren laughed. Toby and Barb looked puzzled.

And there was the important matter of manners to account for. Bren said, under his breath: “Courtesies to the staff, if you please, young lord.”

Cajeiri immediately refocused himself, disengaged, and spotted the important-looking staff quite accurately. Having been properly noticed, they bowed. Cajeiri bowed in return, that slight degree high rank dictated, and Bren said,

“This is Tabini-aiji’s son and heir, Cajeiri. Nandi, this is Ramaso, the major domo of my estate, who bids you welcome.”

“Indeed. One is very pleased to be here.” A second slight bow from the young rascal. “One has heard so much, nadi. Nand’ Bren has told me all about Najida. And he has promised me fishing tomorrow, on his boat.”

“Then that there will be, young lord,” Ramaso said. “The boat is fueled and being made ready, stocked with everything you could wish. And Cook offers a light snack ready, on the chance that young folk may have arrived hungry from such a long trip. Or there is a bath drawn, and a suite made ready should you wish a little rest.”

“Food, nadi! Food, indeed, and one is most grateful!”

“Perhaps the bath should come first,” Bren said, in his capacity as the adult in charge. All three were grimy, and their luggage, which Jegari had carried aboard the bus and off again, consisted of a single duffle, which was hardly enough for the three for seven days. “And staff may sort out your wardrobe.” God only knew what condition the clothes were in by now, in a soft duffle, and packed by these three. “Surely the food may wait an hour more.”

“But we’re starved!” Cajeiri protested in ship-speak, and Bren said, in courtly Ragi:

“A snack, perhaps, delivered bathside. But baths, young gentleman, are definitely in order.” The visible dirt, and the slight air about the three youngsters was notgoing into Ramaso’s tidy dining room. “I am quite firm on this matter, young lord.”

“Well, we shall eat in the tub. Shall Antaro bathe with us? Shall she not have as good as Jegari and I?”

“There is the backstairs bath ready,” Ramaso said. “It is quite a fine bath, nandi.”

“Perfectly adequate,” Bren said firmly, “and Antaro will have a maid’s attendance, and everything sent from the kitchen just as quickly as you. Trust my good staff, young lord, to offer no slight to yours.”

Cajeiri looked at him, and if said young imp had ever observed that Jago shared a bath and a bed with him, and should now mention it, the fishing trip would be in decided jeopardy. Bren made the limits clear in the eye-to-eye glance he returned—Cajeiri being, at eight years of age, about on eye level with him.

The momentary imp faded and left a perfectly agreeable and sensible boy standing there. That boy bowed quite courteously. “We shall be extremely sensible of the honor of your house, nand’ Bren. And we shall not behave badly. We are grateful you were willing to receive us and especially—especially that you felicitously improved the number of our days.”

The imperial we, the language of a century ago, courtly language: that was the dowager’s two years of intense schooling. And the rest of that courtly extravagance? Who knew?

“One is gratified, young lord. You should understand that your esteemed father gave me no chance to ask for the first five days. Your fathersuggested them himself.”

That honestly surprised the boy. “Why did he? Do you know, nandi?”

“Perhaps because he was once your age, and understands the weight of the Bujavid on young shoulders. Perhaps because the world is now somewhat safer than it was, and he wishes you to have a healthy respite from schooling—before the legislature goes into session and the Bujavid exerts itself in even tighter security. He is not ignorant of your considerable accomplishments and your personal efforts over recent months. One believes, in short, it may be a reward in earnest of good behavior.”

Several thoughts flitted through those amber eyes, one of them being, surely, My father is not that tolerant of my misdeeds, and another being, Adults in the world are surely all up to something.

“You doubt my truthfulness, young lord?”

“One certainly would not call the paidhi a liar!”

This from a lad who had grown up where a strong word could bring bloodfeud.

“One would never expect so. One offers one’s personal assessment of the situation. And one hopes for you and yours to be very happy in this visit. We shallhave our fishing trip. And if there had been any advance warning, I should never have scheduled the visit to the neighbors. But perhaps it will not be too boring for you. They will certainly be very excited to meet you. In the meanwhile, we shall have a reasonably early supper tonight, then board the boat in the morning and put out to the head of the bay for some fishing, then out into the wide ocean—well, the straits, which is as large a piece of it as we need—and a little wide-open sailing for the evening. There should be a fair wind beyond the harbor mouth and we shall use the sails.”

“Has it an engine?”

“It does, as does Toby’s, but the sails are the best going.”

Cajeiri’s eyes fairly danced. “One wishes we might stay out for days and days!”

“I shall show you how to steer the boat.”

Truly danced. “We shall be extraordinarily careful, doing so, nand’Bren!”

“Off with you. Wash! Thoroughly!”

“Yes!” Cajeiri said, and was off like a shot, cheerful and eager.

Bren looked at Jago, and at Banichi, who had just come in. Both looked amused.

“It seems very likely the young gentleman and his companions will wish to see the grounds and tour the building before dark. An escort would minimize troublec and keep them off the boat during preparations.”

Banichi laughed outright. “Gladly,” Banichi said.

Banichi had more than once shepherded the boy on the star-ship, but he had had very little time to spend time with Cajeiri since their return, and it was a fortunate solution on all sides. Jago said she would happily rest for a few hours, Tano and Algini were due a chance to go down to the shore, and take in what staff was doing with the boat. So all in all, it was a relatively well-arranged day.

The little hiatus for the youngsters to have their bath and take a tour provided him—granted there was no chance of resuming his speech-writing—time with Toby alone, possibly the chance to have a cautioning word or two with Toby, in fact, and to find out how things stood between them, granted he’d been back on the planet for months and hadn’t had a chance to have a conversation that wasn’t witnessed, managed, or otherwise inconvenient. There was so much they’d never had a chance to discuss: their mother’s last days, when he’d been absent; Toby’s divorce, when he’d been absent; Toby’s meeting up with Barb, when he’d been absentc

And in his imagining this meeting during the long years of the voyage, there’d been all sorts of time for them to sit and talk and reestablish contact. Now—

Now he was down to a few hours before dinner on thisday, before two days or so on the boat with Cajeiri and a day he’d be at the neighboring estatec all of which was adding up to most of a week, when Toby wasn’t going to be here that long. His chances to see Toby for the next number of months would be scant and the chance of something else intervening beyond that was high.

And the longer some things went unsaid, the worse. He didn’t particularly look forward to doing it—but if they let one more meeting go by without ever reforging the links they’d once had—

Well, it just got harder and harder to bring up the topic of his two-year absence, harder for him to find out what had gone on, harder for him and Toby to discuss family business. Harder to be anything but old friends who’d somewhere lost the “brother” part of it all.

They could become more distant than that, if events intervened and made their contacts rarer still. If Toby married Barb, and finally settled. It was a good thing in that sense that Toby had taken to the boat, and lived from port to port. He didn’t know what in hell income his brother was living off of– whether the government runs kept him in fuel and dockage and repairs. And he didn’t ask. Maybe Barb brought in resources. He hoped she did something constructive.

And he really, really wanted not to have Barb in the conversation.

Sure enough, Barb was there when he gave a single rap on the door and walked in on her and Toby in the sitting room of their suite. She was in the act of getting up, perhaps to answer the door—not the atevi way of things. Lacking the formality of a servant’s attendance, and he had absently signaled the maid on duty in the hall that he would not require that—the caller would open the door himself, if it was not locked; and he had done that. He bowed—not their way of things: the bow was as reflexive as the lift of the hand instructing the servant.

“Having a good morning?” he asked.

“A relaxing morning.” Barb went back to sit on the arm of Toby’s chair, a detriment to fine furniture. Absolute anathema to the staff.

He decided not to say anything. It just led to unpleasantness. And he might not, unless he had Barb dropped in the bay, geta chance at Toby alone.

So he did the only thing he could do, decided on intervention, and pulled the cord before he sat down, calling staff to serve a pot of tea.

“I really don’t like tea that well,” Barb said after the door had shut again.

“Well, it’s a bit early for brandy,” he said.

“Your rules,” Barb said with a little laugh, and finally got off the hand-embroidered chair arm, Toby’s hand following her, and trailing off the ends of her fingers. “Rules, rules, rules.”

He smiled, not in the least amused. “They’re everywhere, I’m afraid.” And got down to basic business. “The staff is still prepping the boat. Tano and Algini will be down there supervising. I hope you’ll go along on this trip. I’ve rather assumed you both would.”

“Sure,” Toby said. “Of course we will.”

“The two youngsters with Cajeiri haven’t likely seen water larger than ponds. I hope they won’t be seasick. Probably they won’t be: they’re athletic youngsters. I promised the boy specifically my boat, or we might all of us fit without sleeping bags. But at least one person’s going to end up sleeping on the deckc probably one of my staff.”

“I don’t mind the deck,” Toby said, “but Barb would want a cabin.”

Notably, Barb did not chime in with, oh, no, the deck would be fine.

“No question,” Bren said. “And my staff won’t let me do it, I’m afraid. The kids may want to. It’s an adventure to them. I wouldn’t turn them down. My staff deserves soft beds. But they assuredly won’t let you do it, Toby. Kids are one thing—it’s play for them. But you’re nand’ Toby. Won’t do at all. Dignity and all. Although they did talk about sleeping below the waterline. I think the notion intrigues them.”

“Just the security people are going?” Barb asked.

“Just the four. House staff will be busy here.”

“Not too much for them to do without us,” Toby said.

“Oh, they’re busy: they have the village to look after, too. Not to mention setting things up for the upcoming visit to Kajiminda—that’s Geigi’s estate. They’ll be seeing the bus is in order, that the road over there is decent, all of that. There may be some potholes to fix. Given the recent rain, that’s likely. They arrange things like thatc and that road only gets used maybe once a week, if that.” The tea arrived, and service went around, to Barb as well.

“All right,” Toby said. “Once a week. Why once a week?”

“Market day in the village. The Kajiminda staff will come over and buy supplies. We have the only fish market on the peninsula.”

“Here?” Barb asked.

“The village.” Inspiration struck him. “You asked about shopping. I suppose you might like to do that.”

“Can we?”

“Well, it’s fairly basic shops. There’s a fish market, a pottery, a cordmaker’s, a weaver’s, a woodcrafts shop and a bead-makerc I should send you with one of the maids. They’ll take you to places they know and I don’t.”

Barb’s eyes had gotten considerably brighter. He got up and pulled the cord again, and when the maidservant outside appeared: “Barb-daja would like to go shopping. Kindly take Barb-daja to the market. Just let her buy what she wants on the estate account. Walk with her, speak for her, and keep her safe and out of difficulty, Ika-ji. Take two of the men with you.”

The maid—Ikaro was her name—looked both diffident and cheerful at the prospect—bowed to Barb, and stood immediately waiting.

“Get a wrap,” Bren said. “It’s nippy. People will be curious about you. Just smile, buy what you like or what you might need for the boat. Provisions. I’d meant to send those with you, as was. Pick up some of the local jellies—Ikaro will make sure you get the right ones. —Ika-ji, she may buy foods: no alkaloids.”

“Yes, nandi.”

“Toby?” Barb asked.

“Is it safe?” Toby asked. “You always say—”

“The village is only over the hill and very safe. The men are just to carry packages, in case,” he added with a grin at Barb, “you decide to bring back sacks of flour. Just enjoy yourself. Buy something nice for yourself. You’re on the estate budget. Get something for Toby, too, if you spot something.” He went near and said, into Barb’s ear: “There’s a very good little tackle shop.”

Barb was honestly delighted. She disappeared into the bedroom, with the disconcerted maid in pursuit, and came back with a padded jacket and gloves—and Ikaro.

“You’re sure you’ll be all right?” Toby said, getting to his feet.

“I’ll be perfectly fine,” she said, and proceeded to mortally embarrass the maid by kissing Toby on the mouth, not briefly either, and with a lingering touch on Toby’s cheek. “You be good while I’m gone.”

“I have no choice,” Toby said with a laugh, and the little party got out the door—which shut, and left a small silence behind.

“You’re sure she’ll be all right,” Toby said.

“My staff would die before they let harm come to her,” he said, and sat down and poured a little warmup into his teacup. He had a sip, as Toby settled. “I haven’t had a chance to talk to you, not really. We’ve been in rapid motion—certainly were, the last time we met. It’s been a little chaotic, this time.”

Toby wasn’t stupid. Far from it. He gave an assessing kind of look, beyond a doubt knowing that he’d just maneuvered Barb out the door. “Something serious?”

“Just family business. Not much of it. Nothing I could have done but what I did, but I am lastingly sorry, Toby, for leaving you when I did. I don’t know what more to say. But I am sorry. I had two years out and back to think about that.”

“Hey, you have your job.”

“I am what I am. I don’t regret much, except I know what you went through. I say I know. I intellectually know. I wasn’t there, that’s the point, isn’t it?”

“I read the journal you gave me,” Toby said. “I read every word of it.”

Bren gave an uneasy laugh. “The five-hundred page epic?” It was, in fact, hundreds of pages, uncondensed, but deeply edited—compared to what Tabini had gotten: the whole account of his two years in deep space, hauling back unwilling human colonists from where they had run into serious trouble, trying to prevent a culture clash—the one that might eventually land on their doorstep.

The kyo would arrive as promised, he had every anticipation– a species that had come scarily close to war with a colony that hadn’t asked before it had established itself too near. A colony their own station had had to swallow—a large and unruly item to try to assimilate, given the attitudes in that bundle of humanity.

But that had nothing to do with the situation he’d left Toby in—their mother’s last illness and Toby’s wife walking out, with the kids. Two years. Two years, and no more house with the white picket fence, no more wife, no more kids. Barb and the boat, the Brighter Daysc

“It’s no excuse,” Bren said. “Not from your vantage. Go ahead and say it. I have it coming.

“Say what?” Toby shot back. “Don’t put words in my mouth, brother. Don’t tell me what I think.”

“Maybe you’d tell me.”

“Which is why you maneuvered Barb out of here? She ismy life, Bren. Not just your old girlfriend. She’s my life.”

He didn’t like hearing it. But he nodded, accepting it. All of it. “Good for both of you. If she makes you happy—that’s all that matters.”

“You’re not still in love with her.”

God. He composed himself and said quietly, “No. Definitely I’m not.” And then on to a gentle half-truth. “I hurt her feelings when I broke it off. I was rough about it. She’s still mad at me. And she probably doesn’t want to admit it.” It didn’taccount for Barb making a ridiculous marriage on the rebound, divorcing that man and attaching herself to his and Toby’s mother, and then to Toby. And lying to his brother regarding the evident tension between them wasn’t a good idea. Toby knew him too well, even if Toby didn’t wantto read Barb, in that regard. The hell of it was, Toby wasn’tblind, or stupid, and Toby couldread Barb, which was exactly the problem. “I have every confidence in Barb, when I’m not there provoking her to her worst behavior. Is that honest enough?”

Toby didn’t look happy with the assessment. “It’s probably accurate.”

“Doesn’t mean she loves me. You want my opinion?”

“I have a feeling I’m going to get it.”

“Not if you don’t want it.”

“Damn it, Bren. Fire away.”

“Barb doesn’t turn loose of emotions. She doesn’t always identify them accurately. That’s always been a problem. She’s still charged up about me, but it doesn’t add up to love. There was a time we were really close. I’ve tried to figure what I felt about it, but I’m not sure we ever did get to the love part. Just need-you. A lot of need-you. That was all there ever was. Not healthy for either of us. Now it’s done. Over. Completely. Where you take it from there—I have no control over. I don’t want any.”

Toby nodded. Just nodded. How much, Bren asked himself, how much did Toby add up for himself? How far did he see– when he wanted to?

“I don’t want to lose my brother,” Bren said, as honest as he’d been hedging on the last. “Bottom line. I want you around. As much as can be. I don’t make conditions.”

Second nod.

“You’re mad at me,” Bren said. “You don’t want to be, but you are. Do you want to talk about it?”

Toby shook his head.

“Is it going to go away?” Bren asked. “I’m not so sure it will, until we do talk about it. Is it Mum?”

Toby didn’t look at him on that question.

“It is,” Bren said. “I wasn’t there. Not only at the last. I wasn’t there for years and years before that. Flitting in for a crisis. But you were there every time she needed something. You want my opinion again? You shouldn’t have done it.”

Toby stopped looking at him. Didn’t want to hear it. Never had wanted to hear it.

“Toby, I know it makes you mad. But you were there too often. I’m saying this because I love you. I’m saying this because I was sitting safe and collected on this side of the strait and you were getting the midnight phone calls. I shouldn’t say it, maybe. But I think it and I’m being honest.”

“Think what you like. How was I going to say no?”

“I wish you had. I wish you had, Toby.”

“Shut up. You don’t know a thing about it.”

He nodded. “All right. I’ve said enough.”

“I deserve a woman who was there when I needed her. Barb was there, at the hospital. She was always there. She wasn’t throwing a tantrum every time I had to go and see about Mum. She wasn’t pitching a fit in front of the kids. She wasn’t talking to them about me while I was in Jackson at the hospital. You want the bloody truth, Bren, it was better there than with Jill.”

There was a revelation. The happy home on the beach, the white picket fence, the tidy house and the two kidsc

Toby went home to mother. No matter how rough “home” got, home wasn’t with Jill, not the way Toby remembered things now.

It was also true their mother had had a knack for finding the right psychological moment and ratcheting up the emotional pressurec I need you. Oh, I’ll get along. I had palpitations, is all. Well, go to the doctor, Mother. Oh, no, I don’t need the doctor. Smiles and sunbeams. I’m feeling better. You know I always feel better when you’re herec

After he’d flown home from the continent in the middle of some crisis, because she had one of her own; and she’d hover right over the breakfast table and praise him to the skies and tell Toby what a good son his brother was—salt in the wounds. Absolute salt in the wounds. She’d had Toby rushing to her side because he never loved her enough, never could equal the sacrifices brother Bren made for her, oh, it was so good when Bren was there. She just sparkled.

Hell.

“I love you,” he said to Toby, outright. “I love you even when you’re mad at me—which I don’t blame you for being. You can take a swing at me, if you like.”

“Don’t be ridiculous.”

“It might clear the air.”

“Clear the air, hell! Your bodyguard would blow me to confetti.”

“Well, they’re actually not here, but if you want to, let’s move away from the antique tea service.”

“Now you arebeing ridiculous. Don’t.”

“Well, but I’ll specifically instruct my bodyguard that if you ever do take a swing at me, they’re to let you. You’ve got one on account.”

“Damn it, Bren.”

“Yeah. Honestly, I know more than I look like I do. I know the things Mum did, playing one of us against the other—she did; you know she did. I winced. I didn’t know how to stop it. I honestly didn’t know. I mediate between nations. I couldn’t figure how to tell Mum not to play one of us against the other. She taught me a lot about politics. I never got the better of her.”

“Me either,” Toby said after a moment.

“Did she ever talk about me, you know, that awful Bren? That son that deserted me?”

“No,” Toby said. “You were always the saint.”

“Worse. A lot worse than I thought. I wish she’d damned me now and again. You deserved to hear her say that.”

“Never did.”

“If you’d been the one absent on the continent, you know you’d have been the saint and I’d have been in your spot.”

That was, maybe, a thought Toby hadn’t entertained before now. Toby gave him an odd look.

“So, well, you and Barb can talk about me. Blame me to hell and back. It’s therapeutic.”

“I don’t. She doesn’t. Honestly. She’s not bitter toward you. You want the truth—she’s mad at you. But it’s hurt feelings. Like you say. Hurt feelings.”

“Barb’s probably scared to death we’re getting together to talk about her. She knew damned well I was manuevering her out the door. But the moment dawned, she got her courage together and went shopping. She let us get together and now she doesn’t even know if we’ll make common cause and if she’ll have a boat to get home on. That’s Barb. She’s upset, so she’ll buy something expensive for herself. But she’s brave. At a certain point she canturn loose and take care of herself. That’s the Barb I loved. Back when I did love her, that is.”

Toby managed a dry laugh. “She’ll want to know what we said. And she won’t believe it wasn’t really about her.”

“Better make up something.”

“Hell, Bren!”

“Funny. When I think about thatBarb that just went shopping, I know I probably did love her. But I don’t get that side of Barb anymore. That Barb’s all yours now. I don’t know how long that’ll be so, but I do know she won’t come my way again. It’s guaranteed Jago would shoot both of us.”

“Hell, Bren!”

“Well, Jago would shoot her. That, in Jago’s way of thinking, would solve all the problem.”

“Are you joking or not?”

“I actually don’t know,” he said, and added, dryly, “but I’m certainly not going to ask Jago.”

Toby actually laughed, however briefly, and shook his head, resigning the argument.

“So—are you and Barb going fishing with us after this? Can we share a boat? Or is there too much freight aboard?”

“Sure,” Toby said. “Sure. I honestly look forward to it.”

“Good,” he said, and because the atmosphere in the study was too heavy, too charged: “Want to have a look at the garden? Not much out there, but I can give you the idea. I actually know what’s usually planted there.”

“Sure,” Toby said, so they went out and talked about vegetables.

He went in after a while, and left Toby in the garden, where Toby said he preferred to sit. Barb was still shopping—that was rarely a quick event. The youngsters were settling in. He had– at least an hour to attend his notes. He went to his study then, and wrote an actual three paragraphs of his argument against wireless phones.

Crack.

Possibly the staff doing some maintenance in the formal garden, he thought, and wrote another paragraph.

No, it was notgood for the social fabric for wireless phones to be in every pocket, the ordinary tenor of formal visitation should not be supplanted—

Crack!

Skip and rattle.

That was a peculiar sound. A disturbing question began to nag at him—exactly where the aiji’s son and his companions might be at the moment.

He put away his computer, got up and went out to the hall.

There was no staff. That was unusual. He went down the hall to the youngsters’ room, and found no one there.

That was downright disturbing.

So was the scarcity of staff.

He went to the inner garden door, and walked out into the sunlightc where, indeed, there were staff.

All the staff.

And Banichi. And Toby, and the Taibeni youngsters, all facing the same direction, into the garden.

Crack. Pottery broke.

A smaller figure, one on Toby’s scale, took a step backward, dismayed, with a very human: “Oops.”

Oops, indeed. Bren walked through the melting crowd of servants, saw Ramaso, saw Cajeiri and Toby, saw Banichi on the left. Then he looked right, at the bottom of the garden, and saw a shattered clay pot, with dirt scattered atop the wall and onto the flagstones.

“One will fetch a broom, nandi,” a servant said in a low voice.

“Nandi,” Ramaso said, turning.

Cajeiri looked at him and hid something, hands behind his back, while Toby just shrugged.

“Sorry about that.” Toby gave a little atevi-style bow, showing proper respect for the master of the house.

Bren was a little puzzled. Just a little. He looked at the broken pot, looked at Cajeiri.

“One did aim away from the great window, nandi!” Cajeiri said with a little bow. And added, diffidently, “It was the ricochet that hit it.”

“The ricochet?” he asked, and Cajeiri brought forth to view a curiously familiar object—if they had been on the Island: a forked branch, a length of tubing, probably from the garden shed, and a little patch of leather.

“A slingshota!” Cajeiri announced. “And we are verygood, with almost the first try!”

There had been several tries, one bouncing, probably off the arbor support pillar, into the stained glass window.

“Well,” he said, looking at his brother. “Well, there’sa little cultural transfer for you.”

Toby looked a little doubtful then. “I—just—figured the boy could have missed things, with two formative years up in space.”

Bren pursed his lips. As cultural items went, it was innocuous. Mostly. “You made it.”

“Showed the kids how,” Toby said in a quiet voice. “Mistake?”

“Slingshota,” Bren said, and gave a sigh. “New word for the dictionary. Just never happened to develop on this side of the water, that I know of. Banichi, have you ever seen one?”

“Not in that form,” Banichi said with an amused look. “Not with the stick. Which is quite clever. And the young gentleman has a powerful gripc for his age.”

Witness the demolished potc a rather stout pot at that.

“Well, well,” he said, “use a cheaper target than that, young gentleman, if you please. Set a rock atop the garden wall.”

“I am sorry,” Toby said, coming near him, so seriously contrite that Bren had to laugh and clap him on the shoulder, never mind the witnesses present.

“If the young gentleman takes out the historic ceramics in the Bujavid,” he said, “I may be looking for a home on the island. But no, no damage is done. Just a common pot. I’m sure some entrepreneur will make an industry of this import.” Or the Guild will find use for them, he thought, but didn’t say it. Banichi clearly was taking notes. “Just supervise, will you?”

“No problem,” Toby said, and Bren laughed and patted his shoulder and walked away, Banichi in attendance, to have a word with Ramaso. “Let them have a few empty cans from the kitchen, nadi-ji. That will be a much preferable target.”

“Yes, nandi,” the old man said, and went to shoo the servants back inside.

“Interesting device,” Banichi said. “Not nand’ Toby’s invention.”

“No. Old. Quite old.”

“We have used the spun shot,” Banichi said, “an ancient weapon.”

“Very similar principle,” Bren said. “Except the stick.”

“One does apologize for the pot,” Banichi said.

“Just so it isn’t the dowager’s porcelains, once he gets home.”

“One will have a sobering word with him, Bren-ji.”

“Quietly, ’Nichi-ji. The boy has had a great deal of school and very little amusement since the ship. Perhaps one may put in a word with his father, to find him space in the garden to use his toy.”